"What's Past is Prologue..."

https://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/…/a-tribute-to-legend…

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on June 12, 2013):

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

https://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/…/a-tribute-to-legend…

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on June 12, 2013):

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

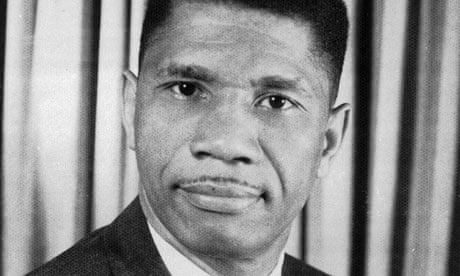

A TRIBUTE TO LEGENDARY CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER AND MISSISSIPPI ACTIVIST MEDGAR EVERS (1925-1963) ON THE 50th ANNIVERSARY OF HIS TRAGIC ASSASSINATION

MEDGAR EVERS

(b. July 2, 1925--d. June 12, 1963)

(b. July 2, 1925--d. June 12, 1963)

All,

Medgar Evers (1925-1963) is one of the central and thus most important figures to emerge in the modern Civil Rights movement that began directly after WWII in the United States. A brilliant visionary, shrewd political strategist, and deeply courageous man who had served his country with great honor, distinction, and bravery throughout Europe fighting fascism in the second world war, a 21 year old Medgar returned to the United States as did hundreds of thousands of his fellow African American veteran soldiers in 1945-46 absolutely determined to confront, challenge, and defeat the ruthlessly racist system of Jim Crow segregation that absolutely ruled his home state of Mississippi as well as the entire southern region of the country with an iron fist and the morally bankrupt sanction of the law--and tellingly in most of the rest of the country as well. Arriving back in his hometown of Jackson, it didn't take long for the ambitious and dynamic Evers to take full advantage of the higher educational opportunities provided by the GI bill that financially enabled an entire generation to attend college. Medgar immediately enrolled in and successfully completed a B.A. program in business administration at Alcorn State College, a well regarded historically black college where he met and soon married Myrlie Beasley in 1951. They had three children and raised a strong family together first in Mound Bayou, Missisippi, and later in Jackson, Miss. while Evers worked as a life insurance salesman for an independently successful black insurance company. Evers's boss T.R.M. Howard was a prominent civil rights activist in his own right and was local President of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL). Through its auspices Evers played a major role in organizing the RCNL's boycott of filling stations that denied black people use of the stations' restrooms. Over the next couple years from 1952-1954 Evers and his brother Charles were very active representatives and organizers of the RCNL's annual conferences which attracted thousands of local black residents.

In 1954 Evers became an even more high profile figure in the burgeoning--and very dangerous--Mississippi civil rights struggle when a highly qualified Evers in a NAACP sponsored legal test case applied to the then completely segregated University of Mississippi. Predictably his application was rejected but Evers's effort galvanized many other black activists throughout the country who were inspired by Evers's courageous example and emulated his activity in many similar anti-segregation cases in the United States. In late 1954 the NAACP officially named Evers its first field secretary in Mississippi. In this leadership capacity Medgar organized many boycotts and established many local chapters of the NAACP. Medgar was also at the epicenter of the heroic desegregation efforts of James Meredith to successfully enroll at the University of Mississippi in 1962 after major violence by enraged white Mississippi students and many local racist thugs who rioted both on and off campus in protest of Meredith's admission were confronted and disarmed by federal troops that President John Kennedy sent to quell the racist violence.

Evers continued as he always had as a dedicated local civil rights leader and organizer in Mississippi who also worked as an investigator in various civil rights cases and incidents around the issues of voter registration (which like in most of the south was still denied to African American citizens), education, and labor rights. For these and other activities Evers was targeted by the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and many other racist organizations throughout the region. For his important public investigations into the vile racist murders of 14 year old Emmitt Till in 1955 and his outspoken support for Clyde Kennard an innocent and brilliant black man (and also WWII veteran) who after trying vainly to transfer from the University of Chicago following his junior year after returned to his native Mississippi to aid a sick and infirm family relative and tried to enroll in a prominent and racially segregated all white Mississippi college. After leading an unsuccessful legal and political effort during the late '1950s to enroll in the school Kennard was framed and falsely imprisoned for burglary because he was seen as a local "troublemaker" for trying to enroll in the school. His case was later thrown out of court years later because of false arrest.

From this point in 1960 onward Medgar was a marked man by the Klan and others for his leadership and on May 28, 1963a Molotov cocktail bomb was thrown into the carport of his home and a week later on June 7, 1963 Evers was nearly run down by a car after he emerged from his Jackson, Mississippi NAACP office. Then just five days later only a few minutes past midnight on June 12, 1963 Medgar was assassinated by a well known KKK and white citizens council member and murderer by the name of Byron De La Beckworth. After being acquited in two all white male deadlocked jury trials in 1964 it would be another 30 years before De La Beckworth was finally convicted and sent to prison where he died at the age of 80 in 2001. It was the fiercely dedicated persistence and deep commitment by Medgar Evers's extraordinary wife and widow who was and is also a civil rights leader and organizer in her own right (and later chairperson during the late 1990s of the NAACP) who diligently fought for the successful reopening of his husband's case over a three decade period that led to finally bring Medgar's racist murderer to justice. At age 80 Mrs. Evers-Williams continues her now 50 year old fight to carry on and implement the tremendous legacy of Medgar's astonishing human and civil right activism on behalf of genuine justice, freedom, and equality today.

The following collection of original texts, videos, recordings, photographs and other pertinent archival information about Medgar Evers's inspiring life and work follows. We offer it all in humble recognition and deep appreciation for what Medgar fought for and achieved during his exceptional life and what now remains for all the rest of us to do both in his personal honor and on behalf of our own collective humanity. Long Live Medgar Evers!...

Kofi

https://mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/medgar-evers-and-the-origin-of-the-civil-rights-movement-in-mississippi

Medgar Evers and the Origin of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi

by Dernoral Davis

Mississippi Historical Society

From this point in 1960 onward Medgar was a marked man by the Klan and others for his leadership and on May 28, 1963a Molotov cocktail bomb was thrown into the carport of his home and a week later on June 7, 1963 Evers was nearly run down by a car after he emerged from his Jackson, Mississippi NAACP office. Then just five days later only a few minutes past midnight on June 12, 1963 Medgar was assassinated by a well known KKK and white citizens council member and murderer by the name of Byron De La Beckworth. After being acquited in two all white male deadlocked jury trials in 1964 it would be another 30 years before De La Beckworth was finally convicted and sent to prison where he died at the age of 80 in 2001. It was the fiercely dedicated persistence and deep commitment by Medgar Evers's extraordinary wife and widow who was and is also a civil rights leader and organizer in her own right (and later chairperson during the late 1990s of the NAACP) who diligently fought for the successful reopening of his husband's case over a three decade period that led to finally bring Medgar's racist murderer to justice. At age 80 Mrs. Evers-Williams continues her now 50 year old fight to carry on and implement the tremendous legacy of Medgar's astonishing human and civil right activism on behalf of genuine justice, freedom, and equality today.

The following collection of original texts, videos, recordings, photographs and other pertinent archival information about Medgar Evers's inspiring life and work follows. We offer it all in humble recognition and deep appreciation for what Medgar fought for and achieved during his exceptional life and what now remains for all the rest of us to do both in his personal honor and on behalf of our own collective humanity. Long Live Medgar Evers!...

Kofi

https://mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/medgar-evers-and-the-origin-of-the-civil-rights-movement-in-mississippi

Medgar Evers and the Origin of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi

by Dernoral Davis

Mississippi Historical Society

Medgar Evers (1925-1963) NAACP field secretary. 1963

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Medgar Evers was buried with military honors at

Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington, D. C.

Medgar Evers statue in Jackson.

October 9, 2009: a dry cargo ammunition ship will be named

the USNS Medgar Evers announced U. S. Secretary of the Navy

Ray Mabus, a former governor of Mississippi.

Courtesy, U. S. Navy.

Mississippi became a major theatre of struggle during the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century because of its resistance to equal rights for its black citizens. Between 1952 and 1963, Medgar Wiley Evers was one of the state’s most impassioned activist, orator, and visionary for change. He fought for equality and fought against brutality.

Born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, Medgar was one of four children born to James and Jesse Evers. His father worked in a sawmill and his mother was a laundress. Evers’s childhood was typical in many ways of black youths who grew up in the Jim Crow South during the Great Depression of the 1930s and in the years preceding World War II. As a youth, Evers’s parents showered him with love and affection, taught him family values, and routinely disciplined him when needed. The Evers home emphasized education, religion, and hard work.

Among his siblings, Evers spent the most time with Charles, whom he idolized. As Evers’s older brother, Charles protected him, taught him to fish, swim, hunt, box, wrestle, and generally served as a sounding board for many of Medgar’s early experiences. He attended all-black schools in the dual and segregated public educational system of Newton County. Segregated public education meant long walks to school for the Evers children. The schools had few resources and operated with outdated textbooks, few teachers, large classes, and small classrooms without laboratories and supplies for the study of biology, chemistry, and physics.

Besides his under-funded public education, Evers on occasion saw and witnessed acts of raw violence against blacks. On these occasions, Evers’s parents and older brother could not shield him from the realities of a society built on racial discrimination. At about age 14, Evers observed to his horror the dragging of a black man, Willie Tingle, behind a wagon through the streets of Decatur. Tingle was later shot and hanged. A friend of Evers’s father, Tingle was accused of insulting a white woman.

Evers later recalled that Tingle’s bloody clothes remained in the field for months near the tree where he was hanged. Each day on his way to school Evers had to pass this tableau of violence. He never forgot the image.

A World War II soldier

At the end of his sophomore year of high school and several months before his eighteenth birthday, Evers volunteered and was inducted into the United States Army in 1942. The decision to volunteer was prompted by a desire to see the world and to follow Charles, who had enlisted a year earlier. During his tour of duty in World War II, Evers was assigned to and served with a segregated port battalion, first in Great Britain and later in France. Though typical at the time, racial segregation in the military only served to anger Evers. By the end of the war, Evers was among a generation of black veterans committed to answering W.E.B. Dubois’s clarion call of nearly three decades earlier: “to return [home] fighting” for change.

Upon returning home, the initial “fight” for Evers was to register to vote. For Evers voting was an affirmation of citizenship. Accordingly, in the summer of 1946, along with his brother, Charles, and several other black veterans, Evers registered to vote at the Decatur city hall. But on election day, the veterans were prevented by angry whites from casting their ballots. The experience only deepened Evers’s conviction that the status quo in Mississippi had to change.

A college student

Evers spent the next decade preparing to become part of the vanguard for change in Mississippi. He returned to school to complete his education under the military’s GI Bill, which was passed by Congress in 1944 to provide education to people who had served in the armed forces during World War II.

In 1946, he enrolled at Alcorn A&M College in Lorman, Mississippi, where he roomed with his brother Charles. At Alcorn, which had both high school and college courses of study, Evers first completed high school and remained to pursue a college degree with a major in business administration.

While in college, Evers met and courted Myrlie Beasley, an education major from Vicksburg. They were married Christmas Eve 1951. Myrlie remembers her initial impressions of Evers as a well-built, self-assured veteran and athlete. Soon afterward she realized he was a “rebel” at heart. “He was ready,” Myrlie recalls, “to put his beliefs to any test. He [even] saw a much larger world than the one that, for the moment, confined him; but he aspired to be a part of that world.”

During his years at Alcorn, Evers enjoyed reading and worked hard to pass all classes. Participation in extracurricular activities remained Evers’s real passion from his freshman year through his senior year. As a freshman he joined the debate team, the business club, played football, and ran track. As a junior he was elected president of his class and vice president of the student forum. By his senior year he had become editor of the Alcorn Yearbook, the student newspaper, the Alcorn Herald, and was named to Who’s Who Among American College Students.

The decision to attend college afforded Evers critical exposure and experiences that contributed to his development as an emerging activist and eventual leader of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. A crucial experience occurred during his senior year when each month he drove to Jackson to participate in an interracial seminar jointly sponsored by then all-white Millsaps and all-black Tougaloo colleges. It was at one of the interracial seminars that Evers became aware of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he subsequently joined.

An insurance agent

After Evers’s graduation, he and Myrlie moved to the all-black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, where he began work as an insurance agent for the Magnolia Mutual Insurance Company, selling life and hospitalization policies to blacks in the Mississippi Delta. The insurance company was owned by Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a black physician in Mound Bayou and a political activist. It was largely because of Howard’s influence that Evers, from 1952 to 1954, not only traveled his Delta route selling insurance, but organized new chapters of the NAACP. The NAACP organizing travels convinced Evers that Jim Crow rendered the state a virtual closed society and that mobilizing at the grassroots level was essential for building a movement for social change. Increasingly, too, Evers saw himself in the vanguard to put an end to Mississippi’s infrastructure of segregation. Other people in the still-young Mississippi Civil Rights Movement also began thinking of Evers as a leader.

The leadership prospects for Evers only increased when he volunteered to become the first black applicant to seek admission to the University of Mississippi. University and state officials reacted to Evers’s January 1954 application for admission to the law school in Oxford with alarm and sought to handle the matter with dispatch. His application was rejected on the “technicality” that it failed to include letters of recommendation from two individuals in the county (Bolivar) where he lived at the time.

NAACP state field secretary

The law school application soon catapulted Evers from relative obscurity to broader name recognition and to serious leadership consideration within the emerging state Civil Rights Movement. E.J. Stringer, president of the NAACP Mississippi State Conference, was so impressed with Evers’s leadership potential that he recommended him for the newly created position of state field secretary of the civil rights organization. The National Office of the NAACP voted in favor of Stringer’s recommendation.

In December 1954, Evers’s appointment as state field secretary was officially announced. The new position required that Evers move from Mound Bayou to Jackson and establish an NAACP field office. Evers negotiated with the NAACP National Office for Myrlie to be appointed as the office’s paid secretary. The Medgar Evers family, which now included two children, Darryl Kenyatta and Reena Denise, came to Jackson in January 1955 – the couple in 1960 had another son, James. Once in Jackson a residence for the family was quickly secured followed by the selection of the new NAACP office in the business hub of the local black community on North Farish Street. Evers relocated the field office ten months later to the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street.

When Evers assumed his position as state field secretary, he began an eight-year career in public life that was both demanding and frustrating. The 1950s proved frustrating and anxiety-laden as some white Mississippians responded with massive resistance to the civil rights activities of the NAACP and to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision which declared segregated schools unconstitutional. There was widespread racial violence against blacks and from 1955 to 1960, Evers faced a range of daunting challenges. He investigated nine racial murders and countless numbers of alleged maltreatment cases involving black victims during the period.

And, Evers’s organizing efforts on behalf of the NAACP proved just as demanding. He worked to promote the growth of adult-lead chapters and to encourage involvement of younger activists in local youth councils across the state. The inclusion of youth, Evers believed, was critical to a winning strategy in the crusade against Jim Crow. In several areas of the state – Jackson, Meridian, McComb, and Vicksburg most notably – youth councils emerged and were quite active. Statewide membership in NAACP chapters nearly doubled between 1956 and 1959 from about 8,000 to 15,000 dues-paying activists.

In the 1960s the agitation for civil rights grew more radical and diverse in its protest strategies. The dominant protest strategies became direct action with civil disobedience, such as boycotts against white merchants. Evers had only limited knowledge of these protest strategies but willingly embraced them to advance the struggle.

On the morning of June 12, 1963, around 12:20 a.m., Medgar Evers arrived home from a long meeting at the New Jerusalem Baptist Church located at 2464 Kelley Street. He got out of his car, arms filled with “Jim Crow Must Go” T-shirts, and walked toward the kitchen door when a shot was fired from a high-powered rifle, striking Evers in the back. Myrlie heard the shot, ran outside with the children behind her, and saw Medgar lying face down in the carport. Next-door-neighbor Houston Wells heard the shot and called the police. The police arrived only minutes later and provided an escort as Wells drove Evers to the emergency room of the University of Mississippi Medical Center on North State Street. Evers died shortly after 1:00 a.m. of loss of blood and internal injuries.

In the initial police investigation, a rifle, which was thought to have fired the fatal shot, was discovered in a thicket of honeysuckle approximately 150 feet from Evers’s carport. White leaders publicly expressed shock and regret. Governor Ross Barnett called the shooting a “dastardly act.” On behalf of the city, Mayor Allen Thompson offered a $5,000 reward for the arrest of the shooter and added that he was “dreadfully shocked, humiliated and sick at heart.”

The day after Evers’s death, several demonstrations broke out in the local black community in reaction to the murder. Black ministers and businessmen joined other angry blacks as they surged out into the streets. Jackson police used force to stop the demonstrations.

On June 15, 1963, Evers’s funeral was held at the Masonic Temple, with Charles Jones, Campbell College chaplain, officiating the service. A special permit was obtained from the city in anticipation of a large funeral cortege and march from the site of the services to Collins Funeral Home. The permit prohibited slogans, shouting, and singing during the funeral procession. After the service about 5,000 mourners joined the procession from the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street, east to Pascagoula, then north onto Farish to the funeral home. When the cortege reached the funeral home, approximately 300 young mourners began singing and moving south in mass toward Capitol Street, the main street of the capital city. The police, who had been shadowing the cortege, responded to mourners by using billy clubs and dogs to disperse them. The crowd then began hurling bricks, bottles, and rocks. A potentially deadly incident was averted when several civil rights workers, and John Doar, a U.S. Justice Department lawyer, beseeched the mourners to stop, which they soon did.

The loss of Medgar Evers was a serious blow to the civil rights struggle across the state. Gone were his imposing presence, compelling oratory, and committed leadership. In a mere eight years, Evers had advanced the civil rights struggle in Mississippi from a fledgling organization to a formidable agent for change.

Medgar Evers is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Despite the loss of Evers’s leadership, the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement forged ahead. The remaining years of the 1960s saw the emergence of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964), Freedom Summer (1964), James Meredith’s March Against Fear (1966), and other protests for racial equality.

On June 22, 1963, Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council, was arrested and charged with the slaying of Medgar Evers. Beckwith was tried twice for Evers’s murder, first in February and later in April 1964. Both trials (before all-white male jurors) ended in hung juries. Beckwith was not retried for the Evers murder until 30 years later. In a two-week trial, held in February 1994 before a jury of eight blacks and four whites, Beckwith was found guilty of the murder of Evers, for which he received a life sentence. Beckwith served only seven years of his life sentence at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County before dying of a heart attack January 21, 2001.

Dernoral Davis, Ph.D., is chairman of the history and philosophy departments, Jackson State University.

Posted October 2003

Bibliography:

Books:

Chafe, William. Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Delaughter, Bobby. Never Too Late: A Prosecutor’s Story of Justice in the Medgar Evers Case. New York: Scribner, 2001.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Evers, Charles. Evers. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1971.

Evers, Myrlie (with William Peters). For Us the Living. New York: Doubleday, 1967. Reprint. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Johnston, Erle. Mississippi’s Defiant Years, 1953-1973. Forest, Mississippi: Lake Haber Publishers, 1990.

Lawson, Steven, and Payne, Charles. Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968. New York: Rowman, Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998.

McMillen, Neil, ed. Remaking Dixie: The Impact of World War II on the American South. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997.

Mendelsohn, Jack. The Martyrs: Sixteen Who Gave Their Lives for Racial Justice. New York: Harper and Row, 1966.

Mottley, Constance Baker. Equal Justice Under Law. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Numan, Bartley. The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South During the 1950s. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Salter, John. Jackson, Mississippi: An American Chronicle of Struggle and Schism. Malabar, Florida: Robert Krueger Publishing Company, 1987.

Articles

Crittendon, Denise. “Medgar Evers Killer Finally Convicted.” Crisis, April 8, 1994.

Evers, Medgar. “Why I Live In Mississippi.” Ebony, September, 1963, 44.

Evers, Myrlie. “He said he wouldn’t mind dying if.” Life, June 28, 1963, 35.

Mitchell, Dennis. “Trial for Honor.” Mindscape (Publication of the Mississippi Committee for the Humanities), 1986, 3-5.

Wynn, Linda. “The Dawning of a New Day: The Nashville Sit-Ins, February 13-May 10, 1960.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol 50 (1991), 42-54.

Pamphlet

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). M is for Mississippi and Murder. New York: NAACP, 1955. This NAACP publication was based on the investigations of Medgar Evers, the newly appointed field secretary for the civil rights organization in Mississippi. The pamphlet provided details on three racial murders in 1955. The three victims were George W. Lee of Belzoni, Lamar Smith of Brookhaven, and Emmett Till, a 14-year-old teenager from Chicago who was visiting his grandfather in Money, Mississippi. At least ten other Black men were racial murder victims during the 1950s in Mississippi.

Mississippi Historical Society © 2000–2013. All rights reserved.

Remembering Medgar Evers: Writing the Long Civil Rights Movement (Mercer University Lamar Memorial Lectures)

by Minrose Gwin

University of Georgia Press, 2013

http://www.democracynow.org/…/medgar_evers_murder_50_years_…

Medgar Evers’ Murder, 50 Years Later: Widow Myrlie Evers-Williams Remembers "A Man for All Time"

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 12, 2013

Medgar Evers’ Murder, 50 Years Later: Widow Myrlie Evers-Williams Remembers "A Man for All Time"

Fifty years ago today — June 12th, 1963 — 37-year-old civil rights organizer Medgar Evers was assassinated in the driveway outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi. In the early 1960s, Evers served as the first NAACP field secretary for Mississippi, where he worked to end segregation, fought for voter rights, struggled to increase black voter registration, led business boycotts, and brought attention to murders and lynchings. We hear from Edgers’ widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, on how she wants her husband to be remembered "a man for all time, one who was totally dedicated to freedom for everyone — and was willing to pay a price."

TRANSCRIPT:

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We end today’s show remembering the life of African-American civil rights activist Medgar Evers. In the early 1960s, Evers served as the first NAACP field secretary for Mississippi, where he worked to end segregation and fought for voter rights. It was 50 years ago today, June 12th, 1963, when the 37-year-old organizer was assassinated in his driveway.

AMY GOODMAN: I recently caught up with his widow, Myrlie Evers, at an NAACP dinner here in New York and asked her how people should remember her husband, for whom she sought justice for so many years.

MYRLIE EVERS-WILLIAMS: Well, what I would encourage young people to do is to go online and find out as much as they can about him, his contributions, to go, believe it or not, to their libraries and do research, and to say to them that he was a man of all time, one who was totally dedicated to freedom for everyone, and was willing to pay a price. And he knew what that price was going to be, but he was willing to pay it. As he said at one of his last speeches, "I love my wife, and I love my children, and I want to create a better life for them and all women and all children, regardless of race, creed or color." I think that kind of sizes him up. He knew what was going to happen. He didn’t want to die, but he was willing to take the risk.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about where he was coming from that night that he was killed in your driveway.

MYRLIE EVERS-WILLIAMS: Medgar was coming from a mass rally that we had two or three times a week, actually. And there had been a meeting after that session, and he was on his way home. I know how weary he was, because he got out of his car on the driver’s side, which was next to the road where the assassin was waiting, and we had determined quite some time ago that we should always get out on the other side of the car. And that night, he got out on the driver’s side with an armful of T-shirts that said "Jim Crow must go." And that bullet struck him in his back, ricocheted throughout his chest, and he lasted 30 minutes after that. And the doctors said they didn’t know how he did. But he was determined to live. The good thing, his body is not here, but he still lives. And I’m very happy, proud and pleased to have played a part in making that come true.

AMY GOODMAN: Myrlie Evers, 50 years ago today, June 12th, 1963, her husband, the civil rights leader Medgar Evers, 37 years old, was assassinated in his driveway in Jackson, Mississippi.

Medgar Evers, Mississippi Martyr

by Michael Vinson Williams

University of Arkansas Press, 2011

Myrlie Evers-Williams On Medgar's Assassination:

The widow of Medgar Evers, Mississippi civil rights activist and former chairperson of the NAACP, Myrlie Evers-Williams talks about both the events leading up to her husband's assassination and the tragic incident itself in interview:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibJFzOBtmag

Born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, Medgar was one of four children born to James and Jesse Evers. His father worked in a sawmill and his mother was a laundress. Evers’s childhood was typical in many ways of black youths who grew up in the Jim Crow South during the Great Depression of the 1930s and in the years preceding World War II. As a youth, Evers’s parents showered him with love and affection, taught him family values, and routinely disciplined him when needed. The Evers home emphasized education, religion, and hard work.

Among his siblings, Evers spent the most time with Charles, whom he idolized. As Evers’s older brother, Charles protected him, taught him to fish, swim, hunt, box, wrestle, and generally served as a sounding board for many of Medgar’s early experiences. He attended all-black schools in the dual and segregated public educational system of Newton County. Segregated public education meant long walks to school for the Evers children. The schools had few resources and operated with outdated textbooks, few teachers, large classes, and small classrooms without laboratories and supplies for the study of biology, chemistry, and physics.

Besides his under-funded public education, Evers on occasion saw and witnessed acts of raw violence against blacks. On these occasions, Evers’s parents and older brother could not shield him from the realities of a society built on racial discrimination. At about age 14, Evers observed to his horror the dragging of a black man, Willie Tingle, behind a wagon through the streets of Decatur. Tingle was later shot and hanged. A friend of Evers’s father, Tingle was accused of insulting a white woman.

Evers later recalled that Tingle’s bloody clothes remained in the field for months near the tree where he was hanged. Each day on his way to school Evers had to pass this tableau of violence. He never forgot the image.

A World War II soldier

At the end of his sophomore year of high school and several months before his eighteenth birthday, Evers volunteered and was inducted into the United States Army in 1942. The decision to volunteer was prompted by a desire to see the world and to follow Charles, who had enlisted a year earlier. During his tour of duty in World War II, Evers was assigned to and served with a segregated port battalion, first in Great Britain and later in France. Though typical at the time, racial segregation in the military only served to anger Evers. By the end of the war, Evers was among a generation of black veterans committed to answering W.E.B. Dubois’s clarion call of nearly three decades earlier: “to return [home] fighting” for change.

Upon returning home, the initial “fight” for Evers was to register to vote. For Evers voting was an affirmation of citizenship. Accordingly, in the summer of 1946, along with his brother, Charles, and several other black veterans, Evers registered to vote at the Decatur city hall. But on election day, the veterans were prevented by angry whites from casting their ballots. The experience only deepened Evers’s conviction that the status quo in Mississippi had to change.

A college student

Evers spent the next decade preparing to become part of the vanguard for change in Mississippi. He returned to school to complete his education under the military’s GI Bill, which was passed by Congress in 1944 to provide education to people who had served in the armed forces during World War II.

In 1946, he enrolled at Alcorn A&M College in Lorman, Mississippi, where he roomed with his brother Charles. At Alcorn, which had both high school and college courses of study, Evers first completed high school and remained to pursue a college degree with a major in business administration.

While in college, Evers met and courted Myrlie Beasley, an education major from Vicksburg. They were married Christmas Eve 1951. Myrlie remembers her initial impressions of Evers as a well-built, self-assured veteran and athlete. Soon afterward she realized he was a “rebel” at heart. “He was ready,” Myrlie recalls, “to put his beliefs to any test. He [even] saw a much larger world than the one that, for the moment, confined him; but he aspired to be a part of that world.”

During his years at Alcorn, Evers enjoyed reading and worked hard to pass all classes. Participation in extracurricular activities remained Evers’s real passion from his freshman year through his senior year. As a freshman he joined the debate team, the business club, played football, and ran track. As a junior he was elected president of his class and vice president of the student forum. By his senior year he had become editor of the Alcorn Yearbook, the student newspaper, the Alcorn Herald, and was named to Who’s Who Among American College Students.

The decision to attend college afforded Evers critical exposure and experiences that contributed to his development as an emerging activist and eventual leader of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. A crucial experience occurred during his senior year when each month he drove to Jackson to participate in an interracial seminar jointly sponsored by then all-white Millsaps and all-black Tougaloo colleges. It was at one of the interracial seminars that Evers became aware of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he subsequently joined.

An insurance agent

After Evers’s graduation, he and Myrlie moved to the all-black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, where he began work as an insurance agent for the Magnolia Mutual Insurance Company, selling life and hospitalization policies to blacks in the Mississippi Delta. The insurance company was owned by Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a black physician in Mound Bayou and a political activist. It was largely because of Howard’s influence that Evers, from 1952 to 1954, not only traveled his Delta route selling insurance, but organized new chapters of the NAACP. The NAACP organizing travels convinced Evers that Jim Crow rendered the state a virtual closed society and that mobilizing at the grassroots level was essential for building a movement for social change. Increasingly, too, Evers saw himself in the vanguard to put an end to Mississippi’s infrastructure of segregation. Other people in the still-young Mississippi Civil Rights Movement also began thinking of Evers as a leader.

The leadership prospects for Evers only increased when he volunteered to become the first black applicant to seek admission to the University of Mississippi. University and state officials reacted to Evers’s January 1954 application for admission to the law school in Oxford with alarm and sought to handle the matter with dispatch. His application was rejected on the “technicality” that it failed to include letters of recommendation from two individuals in the county (Bolivar) where he lived at the time.

NAACP state field secretary

The law school application soon catapulted Evers from relative obscurity to broader name recognition and to serious leadership consideration within the emerging state Civil Rights Movement. E.J. Stringer, president of the NAACP Mississippi State Conference, was so impressed with Evers’s leadership potential that he recommended him for the newly created position of state field secretary of the civil rights organization. The National Office of the NAACP voted in favor of Stringer’s recommendation.

In December 1954, Evers’s appointment as state field secretary was officially announced. The new position required that Evers move from Mound Bayou to Jackson and establish an NAACP field office. Evers negotiated with the NAACP National Office for Myrlie to be appointed as the office’s paid secretary. The Medgar Evers family, which now included two children, Darryl Kenyatta and Reena Denise, came to Jackson in January 1955 – the couple in 1960 had another son, James. Once in Jackson a residence for the family was quickly secured followed by the selection of the new NAACP office in the business hub of the local black community on North Farish Street. Evers relocated the field office ten months later to the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street.

When Evers assumed his position as state field secretary, he began an eight-year career in public life that was both demanding and frustrating. The 1950s proved frustrating and anxiety-laden as some white Mississippians responded with massive resistance to the civil rights activities of the NAACP and to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision which declared segregated schools unconstitutional. There was widespread racial violence against blacks and from 1955 to 1960, Evers faced a range of daunting challenges. He investigated nine racial murders and countless numbers of alleged maltreatment cases involving black victims during the period.

And, Evers’s organizing efforts on behalf of the NAACP proved just as demanding. He worked to promote the growth of adult-lead chapters and to encourage involvement of younger activists in local youth councils across the state. The inclusion of youth, Evers believed, was critical to a winning strategy in the crusade against Jim Crow. In several areas of the state – Jackson, Meridian, McComb, and Vicksburg most notably – youth councils emerged and were quite active. Statewide membership in NAACP chapters nearly doubled between 1956 and 1959 from about 8,000 to 15,000 dues-paying activists.

In the 1960s the agitation for civil rights grew more radical and diverse in its protest strategies. The dominant protest strategies became direct action with civil disobedience, such as boycotts against white merchants. Evers had only limited knowledge of these protest strategies but willingly embraced them to advance the struggle.

On the morning of June 12, 1963, around 12:20 a.m., Medgar Evers arrived home from a long meeting at the New Jerusalem Baptist Church located at 2464 Kelley Street. He got out of his car, arms filled with “Jim Crow Must Go” T-shirts, and walked toward the kitchen door when a shot was fired from a high-powered rifle, striking Evers in the back. Myrlie heard the shot, ran outside with the children behind her, and saw Medgar lying face down in the carport. Next-door-neighbor Houston Wells heard the shot and called the police. The police arrived only minutes later and provided an escort as Wells drove Evers to the emergency room of the University of Mississippi Medical Center on North State Street. Evers died shortly after 1:00 a.m. of loss of blood and internal injuries.

In the initial police investigation, a rifle, which was thought to have fired the fatal shot, was discovered in a thicket of honeysuckle approximately 150 feet from Evers’s carport. White leaders publicly expressed shock and regret. Governor Ross Barnett called the shooting a “dastardly act.” On behalf of the city, Mayor Allen Thompson offered a $5,000 reward for the arrest of the shooter and added that he was “dreadfully shocked, humiliated and sick at heart.”

The day after Evers’s death, several demonstrations broke out in the local black community in reaction to the murder. Black ministers and businessmen joined other angry blacks as they surged out into the streets. Jackson police used force to stop the demonstrations.

On June 15, 1963, Evers’s funeral was held at the Masonic Temple, with Charles Jones, Campbell College chaplain, officiating the service. A special permit was obtained from the city in anticipation of a large funeral cortege and march from the site of the services to Collins Funeral Home. The permit prohibited slogans, shouting, and singing during the funeral procession. After the service about 5,000 mourners joined the procession from the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street, east to Pascagoula, then north onto Farish to the funeral home. When the cortege reached the funeral home, approximately 300 young mourners began singing and moving south in mass toward Capitol Street, the main street of the capital city. The police, who had been shadowing the cortege, responded to mourners by using billy clubs and dogs to disperse them. The crowd then began hurling bricks, bottles, and rocks. A potentially deadly incident was averted when several civil rights workers, and John Doar, a U.S. Justice Department lawyer, beseeched the mourners to stop, which they soon did.

The loss of Medgar Evers was a serious blow to the civil rights struggle across the state. Gone were his imposing presence, compelling oratory, and committed leadership. In a mere eight years, Evers had advanced the civil rights struggle in Mississippi from a fledgling organization to a formidable agent for change.

Medgar Evers is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Despite the loss of Evers’s leadership, the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement forged ahead. The remaining years of the 1960s saw the emergence of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964), Freedom Summer (1964), James Meredith’s March Against Fear (1966), and other protests for racial equality.

On June 22, 1963, Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council, was arrested and charged with the slaying of Medgar Evers. Beckwith was tried twice for Evers’s murder, first in February and later in April 1964. Both trials (before all-white male jurors) ended in hung juries. Beckwith was not retried for the Evers murder until 30 years later. In a two-week trial, held in February 1994 before a jury of eight blacks and four whites, Beckwith was found guilty of the murder of Evers, for which he received a life sentence. Beckwith served only seven years of his life sentence at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County before dying of a heart attack January 21, 2001.

Dernoral Davis, Ph.D., is chairman of the history and philosophy departments, Jackson State University.

Posted October 2003

Bibliography:

Books:

Chafe, William. Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Delaughter, Bobby. Never Too Late: A Prosecutor’s Story of Justice in the Medgar Evers Case. New York: Scribner, 2001.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Evers, Charles. Evers. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1971.

Evers, Myrlie (with William Peters). For Us the Living. New York: Doubleday, 1967. Reprint. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Johnston, Erle. Mississippi’s Defiant Years, 1953-1973. Forest, Mississippi: Lake Haber Publishers, 1990.

Lawson, Steven, and Payne, Charles. Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968. New York: Rowman, Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998.

McMillen, Neil, ed. Remaking Dixie: The Impact of World War II on the American South. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997.

Mendelsohn, Jack. The Martyrs: Sixteen Who Gave Their Lives for Racial Justice. New York: Harper and Row, 1966.

Mottley, Constance Baker. Equal Justice Under Law. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Numan, Bartley. The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South During the 1950s. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Salter, John. Jackson, Mississippi: An American Chronicle of Struggle and Schism. Malabar, Florida: Robert Krueger Publishing Company, 1987.

Articles

Crittendon, Denise. “Medgar Evers Killer Finally Convicted.” Crisis, April 8, 1994.

Evers, Medgar. “Why I Live In Mississippi.” Ebony, September, 1963, 44.

Evers, Myrlie. “He said he wouldn’t mind dying if.” Life, June 28, 1963, 35.

Mitchell, Dennis. “Trial for Honor.” Mindscape (Publication of the Mississippi Committee for the Humanities), 1986, 3-5.

Wynn, Linda. “The Dawning of a New Day: The Nashville Sit-Ins, February 13-May 10, 1960.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol 50 (1991), 42-54.

Pamphlet

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). M is for Mississippi and Murder. New York: NAACP, 1955. This NAACP publication was based on the investigations of Medgar Evers, the newly appointed field secretary for the civil rights organization in Mississippi. The pamphlet provided details on three racial murders in 1955. The three victims were George W. Lee of Belzoni, Lamar Smith of Brookhaven, and Emmett Till, a 14-year-old teenager from Chicago who was visiting his grandfather in Money, Mississippi. At least ten other Black men were racial murder victims during the 1950s in Mississippi.

Mississippi Historical Society © 2000–2013. All rights reserved.

Remembering Medgar Evers: Writing the Long Civil Rights Movement (Mercer University Lamar Memorial Lectures)

by Minrose Gwin

University of Georgia Press, 2013

http://www.democracynow.org/…/medgar_evers_murder_50_years_…

Medgar Evers’ Murder, 50 Years Later: Widow Myrlie Evers-Williams Remembers "A Man for All Time"

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 12, 2013

Medgar Evers’ Murder, 50 Years Later: Widow Myrlie Evers-Williams Remembers "A Man for All Time"

Fifty years ago today — June 12th, 1963 — 37-year-old civil rights organizer Medgar Evers was assassinated in the driveway outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi. In the early 1960s, Evers served as the first NAACP field secretary for Mississippi, where he worked to end segregation, fought for voter rights, struggled to increase black voter registration, led business boycotts, and brought attention to murders and lynchings. We hear from Edgers’ widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, on how she wants her husband to be remembered "a man for all time, one who was totally dedicated to freedom for everyone — and was willing to pay a price."

TRANSCRIPT:

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We end today’s show remembering the life of African-American civil rights activist Medgar Evers. In the early 1960s, Evers served as the first NAACP field secretary for Mississippi, where he worked to end segregation and fought for voter rights. It was 50 years ago today, June 12th, 1963, when the 37-year-old organizer was assassinated in his driveway.

AMY GOODMAN: I recently caught up with his widow, Myrlie Evers, at an NAACP dinner here in New York and asked her how people should remember her husband, for whom she sought justice for so many years.

MYRLIE EVERS-WILLIAMS: Well, what I would encourage young people to do is to go online and find out as much as they can about him, his contributions, to go, believe it or not, to their libraries and do research, and to say to them that he was a man of all time, one who was totally dedicated to freedom for everyone, and was willing to pay a price. And he knew what that price was going to be, but he was willing to pay it. As he said at one of his last speeches, "I love my wife, and I love my children, and I want to create a better life for them and all women and all children, regardless of race, creed or color." I think that kind of sizes him up. He knew what was going to happen. He didn’t want to die, but he was willing to take the risk.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about where he was coming from that night that he was killed in your driveway.

MYRLIE EVERS-WILLIAMS: Medgar was coming from a mass rally that we had two or three times a week, actually. And there had been a meeting after that session, and he was on his way home. I know how weary he was, because he got out of his car on the driver’s side, which was next to the road where the assassin was waiting, and we had determined quite some time ago that we should always get out on the other side of the car. And that night, he got out on the driver’s side with an armful of T-shirts that said "Jim Crow must go." And that bullet struck him in his back, ricocheted throughout his chest, and he lasted 30 minutes after that. And the doctors said they didn’t know how he did. But he was determined to live. The good thing, his body is not here, but he still lives. And I’m very happy, proud and pleased to have played a part in making that come true.

AMY GOODMAN: Myrlie Evers, 50 years ago today, June 12th, 1963, her husband, the civil rights leader Medgar Evers, 37 years old, was assassinated in his driveway in Jackson, Mississippi.

Medgar Evers, Mississippi Martyr

by Michael Vinson Williams

University of Arkansas Press, 2011

Myrlie Evers-Williams On Medgar's Assassination:

The widow of Medgar Evers, Mississippi civil rights activist and former chairperson of the NAACP, Myrlie Evers-Williams talks about both the events leading up to her husband's assassination and the tragic incident itself in interview:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibJFzOBtmag

The Autobiography of Medgar Evers: A Hero's Life and Legacy Revealed Through His Writings, Letters, and Speeches

Edited by Myrlie Evers-Williams and Manning Marable

Basic Civitas Books 2006

PHOTO: MEDGAR EVERS

(b. July 2, 1925--d. June 12, 1963)

Edited by Myrlie Evers-Williams and Manning Marable

Basic Civitas Books 2006

PHOTO: MEDGAR EVERS

(b. July 2, 1925--d. June 12, 1963)