In honor of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968) -- visionary prophet, social activist, cultural critic, public intellectual, community organizer, radical political leader, and profound global advocate and defender of peace, freedom, justice, equality, and human rights whose extraordinary contributions to the history of the ongoing African American liberation struggle in all of its many complex dimensions, and the general mass movements for social, cultural, economic, and political revolution against all forms of racism, sexism, militarism, imperialism, and class domination in the United States and in the rest of the world remain absolutely essential and invaluable to this day.

Kofi

AfroMarxist

June 6, 2018

VIDEO:

Topics: History , Labor

Book Review

The Jack O’Dell Story

by Paul Buhle

May 1, 2011

Democracy Now! is an independent global news hour that airs on over 1,500 TV and radio stations Monday through Friday. Watch our livestream at democracynow.org Mondays to Fridays 8-9 a.m. ET.

Jack O'Dell (1923-2019): Black Activist & Civil Rights Organizer

.jpg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1280)

Bio/Obituary

Wiki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_O%27Dell

New York Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/19/us/jack-odell-dead.html

The Nation

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/who-jack-odell/

Stanford University

https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/odell-hunter-pitts-jack

Writings

The Black Freedom Movement Writings of Jack O'Dell

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppxfh

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520274549/climbin-jacobs-ladder

Archives

New York Public Library: Schomburg

https://archives.nypl.org/scm/21106

Documentary film

The issue of Jack O'Dell

His Voice

On SNYC (Southern Negro Youth Congress)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dfzfhy8y830

On leaving the CPUSA

On Martin Luther King

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=slxGTkKtdxo

On leaving the movement of Martin Luther King

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gBBb7m983Vo

Confronting Racial Capitalism

About Him

Conference

https://labor.washington.edu/odell

The Legacy of Jack O'Dell in the Black Freedom Movement

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YEBdIqWNlqg

Monthly Review

https://monthlyreview.org/2011/05/01/the-jack-odell-story/

Hunter Pitts “Jack” O’Dell (1924-2019)

December 1, 2009

by Melissa Turner

Community organizer and civil rights activist Hunter Pitts O’Dell was born in Detroit, Michigan on August 11, 1924. His father George Edwin O’Dell worked in hotels and restaurants in Detroit. His mother, Emily (Pitts) O’Dell, who studied music at Howard University, later taught adults to play classical piano. O’Dell’s grandparents played a pivotal role in raising him during the turbulent 1930s, and he took his grandfather’s nickname, “Jack,” as his own in order to pay homage to him. O’Dell’s witnessing of racial violence, labor strikes, and social unrest during this period led to his interest in labor and social reform issues.

In 1941, O’Dell left Michigan after high school to attend Xavier University in New Orleans, where he studied pharmacology. He abandoned his studies in order to enlist in the Merchant Marines and fight for the United States during World War II. It was during this period that he became exposed to a variety of progressive and radical thinkers of American and European origins. He also joined an integrated union (the National Maritime Union) and became involved in a variety of civil rights activities. One of these included organizing hotel and restaurant workers in Florida in 1946.

In the 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism in the United States, O’Dell’s left-leaning ideals as well as his membership in the Communist Party USA, led to his expulsion from his union. He remained, however, one of the most energetic and vocal community organizers in the South. He found it difficult to sustain employment because of federal investigations into his political views. O’Dell’s work in the South in the 1950s introduced him to nonviolent resistance as a tactic of the civil rights movement. He claimed to have resigned his Communist Party membership at the end of the 1950s.

While involved in planning the 1959 youth march on Washington for integrated schools, O’Dell became acquainted with major civil rights leaders and strategists such as Martin Luther King Jr., A. Philip Randolph, and Stanley Levison. O’Dell joined King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and was particularly active in planning its successful Birmingham campaign in 1963. O’Dell’s involvement, however, allowed opponents to smear the entire movement as “communist” because of his past membership in the Communist Party. Recognizing that his continued involvement with King and the Southern civil rights movement would continue to be a problem for SCLC, he resigned from the organization late in 1963. After his resignation, O’Dell wrote for Freedomways, a political journal dedicated to black freedom struggles worldwide.

Jack O’Dell continued to be a political activist. He spoke out against the Vietnam War, supported Eugene McCarthy in the late 1960s, worked on Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign, and was involved in a number of civil rights and community organizing events in New York and other cities across the United States.

O’Dell and his wife Jane Power lived in Vancouver, British Columbia. On October 31, 2019, O’Dell died of a stroke at a hospital in Vancouver. He was 96 years old. He is survived by his wife; a daughter, Judith Beatty; a son, Tshaka Lafayette; his brother Edwin; and his sister Carolyn Peart.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Melissa Turner

Melissa Turner is a an independent historian who studies radical historians and intellectuals. She holds advanced degrees in history and political science and is particularly interested in 20th Century thinkers in Western Europe and the United States.

https://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2015/01/in-honor-of-late-dr-martin-luther-king.html

The Radical King

Series: King Legacy (Book 11)

Hardcover: 320 pages

Publisher: Beacon Press (January 13, 2015)

ISBN-10: 0807012823

ISBN-13: 978-0807012826

by Martin Luther King Jr. (Author), Cornel West (Editor)

“The radical King was a democratic socialist who sided with poor and working people in the class struggle taking place in capitalist societies. . . . The response of the radical King to our catastrophic moment can be put in one word: revolution—a revolution in our priorities, a reevaluation of our values, a reinvigoration of our public life, and a fundamental transformation of our way of thinking and living that promotes a transfer of power from oligarchs and plutocrats to everyday people and ordinary citizens. . . . Could it be that we know so little of the radical King because such courage defies our market-driven world?” —Cornel West, from the Introduction

Every year, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is celebrated as one of the greatest orators in US history, an ambassador for nonviolence who became perhaps the most recognizable leader of the civil rights movement. But after more than forty years, few people appreciate how truly radical he was.

Arranged thematically in four parts, The Radical King includes twenty-three selections, curated and introduced by Dr. Cornel West, that illustrate King’s revolutionary vision, underscoring his identification with the poor, his unapologetic opposition to the Vietnam War, and his crusade against global imperialism. As West writes, “Although much of America did not know the radical King—and too few know today—the FBI and US government did. They called him ‘the most dangerous man in America.’ . . . This book unearths a radical King that we can no longer sanitize.”

http://truth-out.org/progressivepicks/item/28568-martin-luther-king-jr-all-labor-has-dignity

Martin Luther King, Jr.: All Labor Has Dignity

Monday, 19 January 2015by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Beacon Press

Book Excerpt

In his introduction to the newly published anthology of King speeches and writings, Cornel West writes, "This book unearths a radical King that we can no longer sanitize." West writes of a charismatic leader who was "anti-imperial, anti-colonial, anti-racist" and embodied "democratic socialist sentiments."

The following is Chapter 21 from The Radical King:

On February 12, 1968—President Lincoln's birthday—as Dr. King traveled from state to state, garnering rousing support for the Poor People's Campaign, more than a thousand sanitation workers in Memphis walked off the job. A month into the strike, on March 18, strikers and their supporters packed Bishop Charles Mason Temple of the Church of God in Christ in what the Reverend James Lawson would describe as a "sardine atmosphere." With few notes, King addressed the overflowing church by connecting the localized strike to the plight of all workers, especially those in the service economy.

[The following speech was delivered by Dr. King in support of the Memphis sanitation workers' strike, just two weeks before he was assassinated in the same city.]

My dear friend James Lawson and to all of these dedicated and distinguished ministers of the gospel assembled here tonight, and to all of the sanitation workers and their families and to all of my brothers and sisters—I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to be in Memphis tonight, and to see you here in such large and enthusiastic numbers.

As I came in tonight, I turned around and said to Ralph Abernathy, "They really have a great movement here in Memphis." You are demonstrating something here that needs to be demonstrated all over our country. You are demonstrating that we can stick together and you are demonstrating that we are all tied in a single garment of destiny, and that if one black person suffers, if one black person is down, we are all down. I've always said that if we are to solve the tremendous problems that we face we are going to have to unite beyond the religious line, and I'm so happy to know that you have done that in this movement in a supportive role. We have Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, members of the Church of God in Christ, and members of the Church of Christ in God, we are all together, and all of the other denominations and religious bodies that I have not mentioned.

But there is another great need, and that is to unite beyond class lines. The Negro "haves" must join hands with the Negro "have-nots." And armed with compassionate traveler checks, they must journey into that other country of their brother's denial and hurt and exploitation. This is what you have done. You've revealed here that you recognize that the no D is as significant as the PhD, and the man who has been to no-house is as significant as the man who has been to Morehouse. And I just want to commend you.

It's been a long time since I've been in a situation like this and this lets me know that we are ready for action. So I come to commend you and I come also to say to you that in this struggle you have the absolute support, and that means financial support also, of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

You are doing many things here in this struggle. You are demanding that this city will respect the dignity of labor. So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs. But let me say to you tonight, that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity, and it has worth. One day our society must come to see this. One day our society will come to respect the sanitation worker if it is to survive, for the person who picks up our garbage, in the final analysis, is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn't do his job, diseases are rampant. All labor has dignity.

But you are doing another thing. You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages. And I need not remind you that this is our plight as a people all over America. The vast majority of Negroes in our country are still perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. My friends, we are living as a people in a literal depression. Now you know when there is mass unemployment and underemployment in the black community they call it a social problem. When there is mass unemployment and underemployment in the white community they call it a depression. But we find ourselves living in a literal depression, all over this country as a people.

Now the problem is not only unemployment. Do you know that most of the poor people in our country are working every day? And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation. These are facts which must be seen, and it is criminal to have people working on a full-time basis and a full-time job getting part-time income. You are here tonight to demand that Memphis will do something about the conditions that our brothers face as they work day in and day out for the well-being of the total community. You are here to demand that Memphis will see the poor.

You know Jesus reminded us in a magnificent parable one day that a man went to hell because he didn't see the poor. His name was Dives. And there was a man by the name of Lazarus who came daily to his gate in need of the basic necessities of life, and Dives didn't do anything about it. And he ended up going to hell. There is nothing in that parable which says that Dives went to hell because he was rich. Jesus never made a universal indictment against all wealth. It is true that one day a rich young ruler came to Him talking about eternal life, and He advised him to sell all, but in that instance Jesus was prescribing individual surgery, not setting forth a universal diagnosis.

If you will go on and read that parable in all of its dimensions and its symbolism you will remember that a conversation took place between heaven and hell. And on the other end of that long-distance call between heaven and hell was Abraham in heaven talking to Dives in hell. It wasn't a millionaire in hell talking with a poor man in heaven, it was a little millionaire in hell talking with a multimillionaire in heaven. Dives didn't go to hell because he was rich. His wealth was his opportunity to bridge the gulf that separated him from his brother Lazarus. Dives went to hell because he passed by Lazarus every day, but he never really saw him. Dives went to hell because he allowed Lazarus to become invisible. Dives went to hell because he allowed the means by which he lived to outdistance the ends for which he lived. Dives went to hell because he maximized the minimum and minimized the maximum. Dives finally went to hell because he sought to be a conscientious objector in the war against poverty.

And I come by here to say that America, too, is going to hell if she doesn't use her wealth. If America does not use her vast resources of wealth to end poverty and make it possible for all of God's children to have the basic necessities of life, she, too, will go to hell. And I will hear America through her historians, years and generations to come, saying, "We built gigantic buildings to kiss the skies. We built gargantuan bridges to span the seas. Through our spaceships we were able to carve highways through the stratosphere. Through our airplanes we are able to dwarf distance and place time in chains. Through our submarines we were able to penetrate oceanic depths."

It seems that I can hear the God of the universe saying, "Even though you have done all of that, I was hungry and you fed me not, I was naked and you clothed me not. The children of my sons and daughters were in need of economic security and you didn't provide it for them. And so you cannot enter the kingdom of greatness." This may well be the indictment on America. And that same voice says in Memphis to the mayor, to the power structure, "If you do it unto the least of these of my children you do it unto me."

Now you are doing something else here. You are highlighting the economic issue. You are going beyond purely civil rights to questions of human rights. That is a distinction.

We've fought the civil rights battle over the years. We've done many electrifying things. Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956, fifty thousand black men and women decided that it was ultimately more honorable to walk the streets in dignity than to ride segregated buses in humiliation. Fifty thousand strong, we substituted tired feet for tired souls. We walked the streets of that city for 381 days until the sagging walls of bus segregation were finally crushed by the battering rams of the forces of justice. In 1960, by the thousands in this city and practically every city across the South, students and even adults started sitting in at segregated lunch counters. As they sat there, they were not only sitting down, but they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and carrying the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy, which were dug deep by the founding fathers in the formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

In 1961, we took a ride for freedom and brought an end to segregation in interstate travel. In 1963, we went to Birmingham, said, "We don't have a right, we don't have access to public accommodations." Bull Connor came with his dogs and he did use them. Bull Connor came with his fire hoses and he did use them. What he didn't realize was that the black people of Birmingham at that time had a fire that no water could put out. We stayed there and worked until we literally subpoenaed the conscience of a large segment of the nation, to appear before the judgment seat of morality on the whole question of civil rights. And then in 1965 we went to Selma. We said, "We don't have the right to vote." And we stayed there, we walked the highways of Alabama until the nation was aroused, and we finally got a voting rights bill.

Now all of these were great movements. They did a great deal to end legal segregation and guarantee the right to vote. With Selma and the voting rights bill one era of our struggle came to a close and a new era came into being. Now our struggle is for genuine equality, which means economic equality. For we know now that it isn't enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn't earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee? What does it profit a man to be able to eat at the swankiest integrated restaurant when he doesn't earn enough money to take his wife out to dine? What does it profit one to have access to the hotels of our city and the motels of our highway when we don't earn enough money to take our family on a vacation? What does it profit one to be able to attend an integrated school when he doesn't earn enough money to buy his children school clothes?

And so we assemble here tonight, and you have assembled for more than thirty days now to say, "We are tired. We are tired of being at the bottom. We are tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression. We are tired of our children having to attend overcrowded, inferior, quality-less schools. We are tired of having to live in dilapidated substandard housing conditions where we don't have wall-to-wall carpets but so often we end up with wall-to-wall rats and roaches. We are tired of smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society. We are tired of walking the streets in search for jobs that do not exist. We are tired of working our hands off and laboring every day and not even making a wage adequate to get the basic necessities of life. We are tired of our men being emasculated so that our wives and our daughters have to go out and work in the white lady's kitchen, leaving us unable to be with our children and give them the time and the attention that they need. We are tired."

And so in Memphis we have begun. We are saying, "Now is the time." Get the word across to everybody in power in this time in this town that now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to make an adequate income a reality for all of God's children. Now is the time for city hall to take a position for that which is just and honest. Now is the time for justice to roll down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream. Now is the time.

Now let me say a word to those of you who are on strike. You have been out now for a number of days, but don't despair. Nothing worthwhile is gained without sacrifice. The thing for you to do is stay together, and say to everybody in this community that you are going to stick it out to the end until every demand is met, and that you are gonna say, "We ain't gonna let nobody turn us around." Let it be known everywhere that along with wages and all of the other securities that you are struggling for, you are also struggling for the right to organize and be recognized.

We can all get more together than we can apart; we can get more organized together than we can apart. And this is the way we gain power. Power is the ability to achieve purpose, power is the ability to affect change, and we need power. What is power? Walter Reuther said once that "power is the ability of a labor union like UAW to make the most powerful corporation in the world—General Motors—say yes when it wants to say no." That's power. And I want you to stick it out so that you will be able to make Mayor Loeb and others say yes, even when they want to say no.

Now the other thing is that nothing is gained without pressure. Don't let anybody tell you to go back on the job and paternalistically say, "Now, you are my men and I'm going to do the right thing for you. Just come on back on the job." Don't go back on the job until the demands are met. Never forget that freedom is not something that is voluntarily given by the oppressor. It is something that must be demanded by the oppressed. Freedom is not some lavish dish that the power structure and the white forces in policy-making positions will voluntarily hand out on a silver platter while the Negro merely furnishes the appetite. If we are going to get equality, if we are going to get adequate wages, we are going to have to struggle for it.

Now you know what? You may have to escalate the struggle a bit. If they keep refusing, and they will not recognize the union, and will not agree for the check-off for the collection of dues, I tell you what you ought to do, and you are together here enough to do it: in a few days you ought to get together and just have a general work stoppage in the city of Memphis.

And you let that day come, and not a Negro in this city will go to any job downtown. When no Negro in domestic service will go to anybody's house or anybody's kitchen. When black students will not go to anybody's school and black teachers . . .

[After conferring with his aides, King returned to the microphone briefly to say he would return to Memphis to lead a mass march within a few days.]Delivered at the American Federation of State, County,

and Municipal Employees mass meeting, Bishop Charles

Mason Temple, Church of God in Christ, Memphis,

Tennessee, March 18, 1968.

Excerpted from The Radical King by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Edited and Introduced by Dr. Cornel West (Beacon Press, 2015). Not to be reposted without permission from the publisher.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Nobel Peace Prize laureate and architect of the nonviolent civil rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was among the twentieth century's most influential figures. One of the greatest orators in US history, King also authored several books, including Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, and Why We Can't Wait. King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968.

Related Stories

Martin Luther King's Vision of Justice

By Eugene Robinson, The Washington Post Writers Group | Op-Ed

Martin Luther King Was a Radical, Not a Saint

By Peter Dreier, Truthout | News Analysis

Black Lives Matter / Black Life Matters: A Conversation with Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore

By Monica J. Casper, The Feminist Wire | Interview

Show Comments

The Center for the study of Race, Politics and Culture at the University of Chicago presented Dr. Cornel West as its annual public lecture on February 1, 2015 at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel:

VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-tLcoNXk8OI

https://www.youtube.com/embed/-tLcoNXk8OI

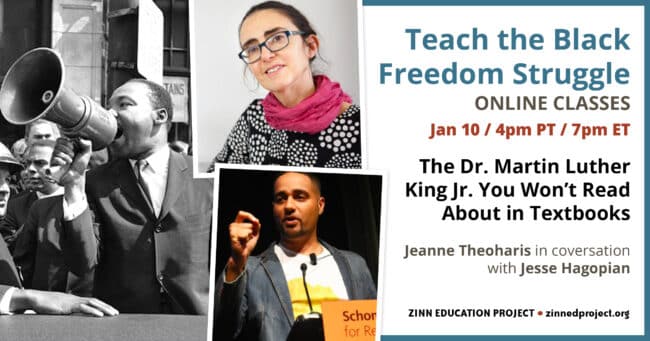

The Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. You Won’t Read About in Textbooks

January 11, 2022

As Theoharis notes in an article in The Atlantic, “Critics of Black Lives Matter have held up King as a foil to the movement’s criticisms of law enforcement, but those are views that King himself shared. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed, ‘We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.’ King understood that police brutality — like segregation — wasn’t just a southern problem.”

Here are a few reactions from participants:

My instruction is now more informed with truth and I am able to provide a broader context for his work.

Dr. Theoharis’ scholarship helps me understand civil rights history in a way that I was never taught. Thank you.

I learned that Dr. King’s public persona was definitely white-washed to make him more acceptable to the white audience and less intimidating, as well.

Jeanne Theoharis had the presence of mind to ground us in the difficulties of the struggle today for educators. Jesse Hagopian followed suit and signified how hard the work is at this moment in these grim conditions.

Thanks so much. This community means a great deal to me. The ideas embolden my political imagination and offer succor. I also just love seeing people who are in the struggle for radical education.

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript: