Peril

by Toni Morrison

by Toni Morrison

[First published in Burn This Book: PEN Writers Speak Out on the Power of the Word (2009); reprinted in The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations (2019)]

Authoritarian regimes, dictators, despots are often, but not always, fools. But none is foolish enough to give perceptive, dissident writers free range to publish their judgments or follow their creative instincts. They know they do so at their own peril. They are not stupid enough to abandon control (overt or insidious) over media. Their methods include surveillance, censorship, arrest, even slaughter of those writers informing and disturbing the public. Writers who are unsettling, calling into question, taking another, deeper look. Writers—journalists, essayists, bloggers, poets, playwrights—can disturb the social oppression that functions like a coma on the population, a coma despots call peace, and they stanch the blood flow of war that hawks and profiteers thrill to.

That is their peril.

Ours is of another sort.

How bleak, unlivable, insufferable existence becomes when we are deprived of artwork. That the life and work of writers facing peril must be protected is urgent, but along with that urgency we should remind ourselves that their absence, the choking off of a writer’s work, its cruel amputation, is of equal peril to us. The rescue we extend to them is a generosity to ourselves.

We all know nations that can be identified by the flight of writers from their shores. These are regimes whose fear of unmonitored writing is justified because truth is trouble. It is trouble for the warmonger, the torturer, the corporate thief, the political hack, the corrupt justice system, and for a comatose public. Unpersecuted, unjailed, unharassed writers are trouble for the ignorant bully, the sly racist, and the predators feeding off the world’s resources. The alarm, the disquiet, writers raise is instructive because it is open and vulnerable, because if unpoliced it is threatening. Therefore the historical suppression of writers is the earliest harbinger of the steady peeling away of additional rights and liberties that will follow. The history of persecuted writers is as long as the history of literature itself. And the efforts to censor, starve, regulate, and annihilate us are clear signs that something important has taken place. Cultural and political forces can sweep clean all but the “safe,” all but state-approved art.

I have been told that there are two human responses to the perception of chaos: naming and violence. When the chaos is simply the unknown, the naming can be accomplished effortlessly—a new species, star, formula, equation, prognosis. There is also mapping, charting, or devising proper nouns for unnamed or stripped-of-names geography, landscape, or population. When chaos resists, either by reforming itself or by rebelling against imposed order, violence is understood to be the most frequent response and the most rational when confronting the unknown, the catastrophic, the wild, wanton, or incorrigible. Rational responses may be censure; incarceration in holding camps, prisons; or death, singly or in war. There is, however, a third response to chaos, which I have not heard about, which is stillness. Such stillness can be passivity and dumbfoundedness; it can be paralytic fear. But it can also be art. Those writers plying their craft near to or far from the throne of raw power, of military power, of empire building and countinghouses, writers who construct meaning in the face of chaos must be nurtured, protected. And it is right that such protection be initiated by other writers. And it is imperative not only to save the besieged writers but to save ourselves. The thought that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing underground, essayists’ questions challenging authority never being posed, unstaged plays, canceled films—that thought is a nightmare. As though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.

Certain kinds of trauma visited on peoples are so deep, so cruel, that unlike money, unlike vengeance, even unlike justice, or rights, or the goodwill of others, only writers can translate such trauma and turn sorrow into meaning, sharpening the moral imagination.

A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity.

TONI MORRISON (1931-2019)

"Racism and Facism"

by Toni Morrison

1995

Let us be reminded that before there is a final solution, there must be a first solution, a second one, even a third. The move toward a final solution is not a jump. It takes one step, then another, then another. Something, perhaps, like this:

(1) Construct an internal enemy, as both focus and diversion.

(2) Isolate and demonize that enemy by unleashing and protecting the utterance of overt and coded name-calling and verbal abuse. Employ ad hominem attacks as legitimate charges against that enemy.

(3) Enlist and create sources and distributors of information who are willing to reinforce the demonizing process because it is profitable, because it grants power, and because it works.

(4) Palisade all art forms; monitor, discredit or expel those that challenge or destabilize processes of demonization and deification.

(5) Subvert and malign all representatives of and sympathizers with this constructed enemy.

(6) Solicit, from among the enemy, collaborators who agree with and can sanitize the dispossession process.

(7) Pathologize the enemy in scholarly and popular mediums; recycle, for example, scientific racism and the myths of racial superiority in order to naturalize the pathology.

In 1995 racism may wear a new dress, buy a new pair of boots, but neither it nor its succubus twin fascism is new or can make anything new. It can only reproduce the environment that supports its own health: fear, denial and an atmosphere in which its victims have lost the will to fight.

(8) Criminalize the enemy. Then prepare, budget for and rationalize the building of holding arenas for the enemy — especially its males and absolutely its children.

(9) Reward mindlessness and apathy with monumentalized entertainments and with little pleasures, tiny seductions: a few minutes on television, a few lines in the press; a little pseudosuccess; the illusion of power and influence; a little fun, a little style, a little consequence.

(10) Maintain, at all costs, silence.

In 1995 racism may wear a new dress, buy a new pair of boots, but neither it nor its succubus twin fascism is new or can make anything new. It can only reproduce the environment that supports its own health: fear, denial and an atmosphere in which its victims have lost the will to fight.

The forces interested in fascist solutions to national problems are not to be found in one political party or another, or in one or another wing of any single political party. Democrats have no unsullied history of egalitarianism. Nor are liberals free of domination agendas. Republicans may have housed abolitionists and white supremacists. Conservative, moderate, liberal; right, left, hard left, far right; religious, secular, socialist — we must not be blindsided by these Pepsi-Cola, Coca-Cola labels because the genius of fascism is that any political structure can host the virus and virtually any developed country can become a suitable home. Fascism talks ideology, but it is really just marketing — marketing for power.

Conservative, moderate, liberal; right, left, hard left, far right; religious, secular, socialist—we must not be blindsided by these Pepsi-Cola, Coca-Cola labels because the genius of fascism is that any political structure can host the virus.

It is recognizable by its need to purge, by the strategies it uses to purge, and by its terror of truly democratic agendas. It is recognizable by its determination to convert all public services to private entrepreneurship; all nonprofit organizations to profit-making ones — so that the narrow but protective chasm between governance and business disappears. It changes citizens into taxpayers — so individuals become angry at even the notion of the public good. It changes neighbors into consumers — so the measure of our value as humans is not our humanity or our compassion or our generosity but what we own. It changes parenting into panicking — so that we vote against the interests of our own children; against their health care, their education, their safety from weapons. And in effecting these changes it produces the perfect capitalist, one who is willing to kill a human being for a product (a pair of sneakers, a jacket, a car) or kill generations for control of products (oil, drugs, fruit, gold).

When our fears have all been serialized, our creativity censured, our ideas “marketplaced,” our rights sold, our intelligence sloganized, our strength downsized, our privacy auctioned; when the theatricality, the entertainment value, the marketing of life is complete, we will find ourselves living not in a nation but in a consortium of industries, and wholly unintelligible to ourselves except for what we see as through a screen darkly.

by Toni Morrison

1995

Let us be reminded that before there is a final solution, there must be a first solution, a second one, even a third. The move toward a final solution is not a jump. It takes one step, then another, then another. Something, perhaps, like this:

(1) Construct an internal enemy, as both focus and diversion.

(2) Isolate and demonize that enemy by unleashing and protecting the utterance of overt and coded name-calling and verbal abuse. Employ ad hominem attacks as legitimate charges against that enemy.

(3) Enlist and create sources and distributors of information who are willing to reinforce the demonizing process because it is profitable, because it grants power, and because it works.

(4) Palisade all art forms; monitor, discredit or expel those that challenge or destabilize processes of demonization and deification.

(5) Subvert and malign all representatives of and sympathizers with this constructed enemy.

(6) Solicit, from among the enemy, collaborators who agree with and can sanitize the dispossession process.

(7) Pathologize the enemy in scholarly and popular mediums; recycle, for example, scientific racism and the myths of racial superiority in order to naturalize the pathology.

In 1995 racism may wear a new dress, buy a new pair of boots, but neither it nor its succubus twin fascism is new or can make anything new. It can only reproduce the environment that supports its own health: fear, denial and an atmosphere in which its victims have lost the will to fight.

(8) Criminalize the enemy. Then prepare, budget for and rationalize the building of holding arenas for the enemy — especially its males and absolutely its children.

(9) Reward mindlessness and apathy with monumentalized entertainments and with little pleasures, tiny seductions: a few minutes on television, a few lines in the press; a little pseudosuccess; the illusion of power and influence; a little fun, a little style, a little consequence.

(10) Maintain, at all costs, silence.

In 1995 racism may wear a new dress, buy a new pair of boots, but neither it nor its succubus twin fascism is new or can make anything new. It can only reproduce the environment that supports its own health: fear, denial and an atmosphere in which its victims have lost the will to fight.

The forces interested in fascist solutions to national problems are not to be found in one political party or another, or in one or another wing of any single political party. Democrats have no unsullied history of egalitarianism. Nor are liberals free of domination agendas. Republicans may have housed abolitionists and white supremacists. Conservative, moderate, liberal; right, left, hard left, far right; religious, secular, socialist — we must not be blindsided by these Pepsi-Cola, Coca-Cola labels because the genius of fascism is that any political structure can host the virus and virtually any developed country can become a suitable home. Fascism talks ideology, but it is really just marketing — marketing for power.

Conservative, moderate, liberal; right, left, hard left, far right; religious, secular, socialist—we must not be blindsided by these Pepsi-Cola, Coca-Cola labels because the genius of fascism is that any political structure can host the virus.

It is recognizable by its need to purge, by the strategies it uses to purge, and by its terror of truly democratic agendas. It is recognizable by its determination to convert all public services to private entrepreneurship; all nonprofit organizations to profit-making ones — so that the narrow but protective chasm between governance and business disappears. It changes citizens into taxpayers — so individuals become angry at even the notion of the public good. It changes neighbors into consumers — so the measure of our value as humans is not our humanity or our compassion or our generosity but what we own. It changes parenting into panicking — so that we vote against the interests of our own children; against their health care, their education, their safety from weapons. And in effecting these changes it produces the perfect capitalist, one who is willing to kill a human being for a product (a pair of sneakers, a jacket, a car) or kill generations for control of products (oil, drugs, fruit, gold).

When our fears have all been serialized, our creativity censured, our ideas “marketplaced,” our rights sold, our intelligence sloganized, our strength downsized, our privacy auctioned; when the theatricality, the entertainment value, the marketing of life is complete, we will find ourselves living not in a nation but in a consortium of industries, and wholly unintelligible to ourselves except for what we see as through a screen darkly.

TONI MORRISON SPEAKING:

"This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal."

I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge — even wisdom."

https://www.thenation.com/…/toni-morrison-essays-fiction-h…/

"...Morrison did all of this fearlessly, no matter the costs that came with forcing American culture to come to her and her people. She composed her novels, edited her books, and published her literary criticism knowing that she could write circles around her critics—and often did. No one has gone to bat for William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner since. The genuflecting esteem and towering fame accorded to writers like John Updike and Norman Mailer have never recovered. Others played a role in this too, but Morrison’s critiques were hard to look past, and the due respect accorded to female novelists white, black, and of every other shade owes something to her epochal impact on the “literary field,” as Pierre Bourdieu would put it. That Morrison will always be read first and foremost as a novelist is, of course, as it should be. But the tremendous impact of her fiction and her very public career as a novelist have tended to eclipse her contributions as a moral and political essayist, which the pieces gathered in The Source of Self-Regard help correct. Taken together with What Moves at the Margin, her first volume of nonfiction, as well as Playing in the Dark and The Origin of Others, her 2017 collection of lectures, this final book brings Morrison the moral and social critic into view.

In her essays, lectures, and reviews, we discover a writer working in a register that many readers may not readily associate with her. Rather than the deft orchestrator of ritual and fable, chronicler of the material and spiritual experience of black girlhood, and master artificer of the vernacular constitution of black communal life, here we encounter Morrison as a dispassionate social theorist and moral anthropologist, someone who offers acute and even scathing readings of America’s contemporary malaise and civic and moral decline in an age defined by the mindless boosterism of laissez-faire capitalism.

In essays like “The Foreigner’s Home,” one almost hears echoes of Jean Baudrillard’s theories of simulated life under late capitalism and Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle as she examines the disorienting loss of distinction between private and public space and its effect on our interior lives. The politicization of the “migrant” and the “illegal alien,” Morrison argues, is not merely a circling of the wagons in the face of “the transglobal tread of peoples.” It is also an act of bad faith, a warped projection of our fears of homelessness and “our own rapidly disintegrating sense of belonging” reflecting the anxieties produced by the privatization of public goods and commons and the erosion of face-to-face association. Our lives, Morrison tells us, have now become refracted through a “looking-glass” that has compressed our public and private lives “into a ubiquitous blur” and created a pressure that “can make us deny the foreigner in ourselves.”

In other essays, one finds Morrison venturing bravely into the tense intersections of race, gender, class, and radical politics. The essay “Women, Race, and Memory,” written in 1989, offers a retrospective attempt to make sense of the fractures within the 1960s and ’70s left, to understand why a set of interlocking liberation struggles ended up splitting along racial, gender, and class lines. One can’t help feeling a wincing recognition when Morrison writes of “the internecine conflicts, cul-de-sacs, and mini-causes that have shredded the [women’s] movement.” On top of racial divides, she asserts, class fissures broke apart a movement just as it was coming together, exacerbating “the differences between black and white women, poor and rich women, old and young women, single welfare mothers and single employed mothers.” Class and race, Morrison laments, ended up pitting “women against one another in male-invented differences of opinion—differences that determine who shall work, who shall be well educated, who controls the womb and/or the vagina; who goes to jail, who lives where.” Achieving solidarity may be daunting, but the alternative is “a slow and subtle form of sororicide. There is no one to save us from that,” Morrison cautions—“no one except ourselves.”

Even as her essays ranged widely, from dissections of feminist politics to the rise of African literature, from extolling the achievements of black women (“you are what fashion tries to be—original and endlessly refreshing”) to the parallels between modern and medieval conceptions of violence and conflict in Beowulf, they came together around a set of core concerns about the degradation and coarsening of our politics as we cast one another as others and how this process often manifests itself through language.

This is particularly true of the essays included in The Source of Self-Regard, which give their readers little doubt about the power of her insights when she trains her eye on the dismal state of contemporary politics and asks how the rhetoric and experiences of otherness came to be transformed by the rise of new media and global free-market fundamentalism into a potent source of reactionary friction. Despite the fact that some of these essays are now several decades old, Morrison’s insights are still relevant. For example, her gimlet-eyed description of the cant of our political class in the essay “Wartalk,” that “empurpled comic-book language in which they express themselves.” Or her warning against “being bullied” by those in power “into understanding the human project as a manliness contest where women and children are the most dispensable collateral.” Or her chiding of the “commercial media” in the run-up to the Iraq War for echoing the uninterrogated lines of Tony Blair and George W. Bush. Journalists, she insisted, must take up the cause of fighting “against cultivated ignorance, enforced silence, and metastasizing lies.” They are not supposed to contribute to it.

The sheer quantity of her speeches and essays testifies to Morrison’s power as a moral and social critic. But this does not mean she left literature entirely behind in her essays. In fact, the greater part of The Source of Self-Regard is dedicated to her applying her moral and political insights in the arena of art as well. Fiction writers are not always the best readers of their own work or others’. (It’s only natural that they have their blind spots.) Yet Morrison proves to be a literary critic of the highest order, besotted with the intricacies and pleasures of textual interpretation and with their political and moral import and enviably providing such close readings of her own work that we are sometimes left wondering whether there is anything else for us to really say.

In her 1988 lecture “Unspeakable Things Unspoken,” she provides a carefully argued account of black literature in relation to the Western canon (while, in passing, wonderfully provincializing Milan Kundera’s Europhilia in The Art of the Novel) before peeling back the layers of her creative process and guiding us through her decisions, omissions, and qualified judgments as a novelist, from the opening sentences of her novels to their concluding lines. “There is something about numerals,” she explains in a passage on the famous opening of Beloved (“124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom”),

that makes them spoken, heard, in this context, because one expects words to read in a book, not numbers to say, or hear. And the sound of the novel, sometimes cacophonous, sometimes harmonious, must be an inner-ear sound or a sound just beyond hearing, infusing the text with a musical emphasis that words can do sometimes even better than music can. Thus the second sentence is not one: it is a phrase that properly, grammatically, belongs as a dependent clause with the first…. The reader is snatched, yanked, thrown into an environment completely foreign…snatched just as the slaves were from one place to another, from any place to another, without preparation and without defense.

Reading her pieces on literature, one immediately recognizes that, for Morrison, literary criticism was also an art, the essay another vehicle for conveying her moral and political insights. Her skills as a writer of nonfiction are one and the same as her powers as a writer of fiction. For her, both the essay and the novel can undo the work of individuation foisted upon us by modern society; they can bring “others” into contact and remind us of our common humanity.

Sometimes this larger project of humanization can show itself in the choice of a single word, like the solemn weight and subtle inflections of the adjective “educated” as it describes Paul D’s hands in Beloved as he and Sethe fumble toward the beginnings of a new life eked out within the living memory of enslavement. Other times it expresses itself in a lyrical outburst that captures a fleeting moment of self-fashioned freedom, a world of possibility momentarily gleaned from an otherwise desperate circumstance, as in this passage from Jazz:

Oh, the room—the music—the people leaning in doorways. This is the place where things pop. This is the market where gesture is all: a tongue’s lightning lick; a thumbnail grazing the split cheeks of a purple plum.

Finding those places where things pop is the central task of her humanism, which she calls, in the titular essay of the new collection, the act of “self-regard.” Self-regard, Morrison insists, is the process in which we recover our selves—in which we once again become human. It means experiencing black culture “from a viewpoint that precedes its appropriation”; it means seeing humanity after the veil of otherness has fallen. By stirring people into prideful expression, self-regard can help us see through the literalism and literal-mindedness that centuries of racist thought and practice that has prevented us from being better readers of our lives and, in turn, others’..."

--Jesse McCarthy--"The radical vision of Toni Morrison”, The Nation, December 16, 2019

Books of Literary Criticism by Toni Morrison:

PHOTO: Playing in the Dark by Toni Morrison, 1992

PHOTO: What Moves At The Margins by Toni Morrison, 2008

PHOTO: The Origins of Others by Toni Morrison, 2017

PHOTO: The Source of Self Regard by Toni Morrison, 2019

I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge — even wisdom."

https://www.thenation.com/…/toni-morrison-essays-fiction-h…/

"...Morrison did all of this fearlessly, no matter the costs that came with forcing American culture to come to her and her people. She composed her novels, edited her books, and published her literary criticism knowing that she could write circles around her critics—and often did. No one has gone to bat for William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner since. The genuflecting esteem and towering fame accorded to writers like John Updike and Norman Mailer have never recovered. Others played a role in this too, but Morrison’s critiques were hard to look past, and the due respect accorded to female novelists white, black, and of every other shade owes something to her epochal impact on the “literary field,” as Pierre Bourdieu would put it. That Morrison will always be read first and foremost as a novelist is, of course, as it should be. But the tremendous impact of her fiction and her very public career as a novelist have tended to eclipse her contributions as a moral and political essayist, which the pieces gathered in The Source of Self-Regard help correct. Taken together with What Moves at the Margin, her first volume of nonfiction, as well as Playing in the Dark and The Origin of Others, her 2017 collection of lectures, this final book brings Morrison the moral and social critic into view.

In her essays, lectures, and reviews, we discover a writer working in a register that many readers may not readily associate with her. Rather than the deft orchestrator of ritual and fable, chronicler of the material and spiritual experience of black girlhood, and master artificer of the vernacular constitution of black communal life, here we encounter Morrison as a dispassionate social theorist and moral anthropologist, someone who offers acute and even scathing readings of America’s contemporary malaise and civic and moral decline in an age defined by the mindless boosterism of laissez-faire capitalism.

In essays like “The Foreigner’s Home,” one almost hears echoes of Jean Baudrillard’s theories of simulated life under late capitalism and Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle as she examines the disorienting loss of distinction between private and public space and its effect on our interior lives. The politicization of the “migrant” and the “illegal alien,” Morrison argues, is not merely a circling of the wagons in the face of “the transglobal tread of peoples.” It is also an act of bad faith, a warped projection of our fears of homelessness and “our own rapidly disintegrating sense of belonging” reflecting the anxieties produced by the privatization of public goods and commons and the erosion of face-to-face association. Our lives, Morrison tells us, have now become refracted through a “looking-glass” that has compressed our public and private lives “into a ubiquitous blur” and created a pressure that “can make us deny the foreigner in ourselves.”

In other essays, one finds Morrison venturing bravely into the tense intersections of race, gender, class, and radical politics. The essay “Women, Race, and Memory,” written in 1989, offers a retrospective attempt to make sense of the fractures within the 1960s and ’70s left, to understand why a set of interlocking liberation struggles ended up splitting along racial, gender, and class lines. One can’t help feeling a wincing recognition when Morrison writes of “the internecine conflicts, cul-de-sacs, and mini-causes that have shredded the [women’s] movement.” On top of racial divides, she asserts, class fissures broke apart a movement just as it was coming together, exacerbating “the differences between black and white women, poor and rich women, old and young women, single welfare mothers and single employed mothers.” Class and race, Morrison laments, ended up pitting “women against one another in male-invented differences of opinion—differences that determine who shall work, who shall be well educated, who controls the womb and/or the vagina; who goes to jail, who lives where.” Achieving solidarity may be daunting, but the alternative is “a slow and subtle form of sororicide. There is no one to save us from that,” Morrison cautions—“no one except ourselves.”

Even as her essays ranged widely, from dissections of feminist politics to the rise of African literature, from extolling the achievements of black women (“you are what fashion tries to be—original and endlessly refreshing”) to the parallels between modern and medieval conceptions of violence and conflict in Beowulf, they came together around a set of core concerns about the degradation and coarsening of our politics as we cast one another as others and how this process often manifests itself through language.

This is particularly true of the essays included in The Source of Self-Regard, which give their readers little doubt about the power of her insights when she trains her eye on the dismal state of contemporary politics and asks how the rhetoric and experiences of otherness came to be transformed by the rise of new media and global free-market fundamentalism into a potent source of reactionary friction. Despite the fact that some of these essays are now several decades old, Morrison’s insights are still relevant. For example, her gimlet-eyed description of the cant of our political class in the essay “Wartalk,” that “empurpled comic-book language in which they express themselves.” Or her warning against “being bullied” by those in power “into understanding the human project as a manliness contest where women and children are the most dispensable collateral.” Or her chiding of the “commercial media” in the run-up to the Iraq War for echoing the uninterrogated lines of Tony Blair and George W. Bush. Journalists, she insisted, must take up the cause of fighting “against cultivated ignorance, enforced silence, and metastasizing lies.” They are not supposed to contribute to it.

The sheer quantity of her speeches and essays testifies to Morrison’s power as a moral and social critic. But this does not mean she left literature entirely behind in her essays. In fact, the greater part of The Source of Self-Regard is dedicated to her applying her moral and political insights in the arena of art as well. Fiction writers are not always the best readers of their own work or others’. (It’s only natural that they have their blind spots.) Yet Morrison proves to be a literary critic of the highest order, besotted with the intricacies and pleasures of textual interpretation and with their political and moral import and enviably providing such close readings of her own work that we are sometimes left wondering whether there is anything else for us to really say.

In her 1988 lecture “Unspeakable Things Unspoken,” she provides a carefully argued account of black literature in relation to the Western canon (while, in passing, wonderfully provincializing Milan Kundera’s Europhilia in The Art of the Novel) before peeling back the layers of her creative process and guiding us through her decisions, omissions, and qualified judgments as a novelist, from the opening sentences of her novels to their concluding lines. “There is something about numerals,” she explains in a passage on the famous opening of Beloved (“124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom”),

that makes them spoken, heard, in this context, because one expects words to read in a book, not numbers to say, or hear. And the sound of the novel, sometimes cacophonous, sometimes harmonious, must be an inner-ear sound or a sound just beyond hearing, infusing the text with a musical emphasis that words can do sometimes even better than music can. Thus the second sentence is not one: it is a phrase that properly, grammatically, belongs as a dependent clause with the first…. The reader is snatched, yanked, thrown into an environment completely foreign…snatched just as the slaves were from one place to another, from any place to another, without preparation and without defense.

Reading her pieces on literature, one immediately recognizes that, for Morrison, literary criticism was also an art, the essay another vehicle for conveying her moral and political insights. Her skills as a writer of nonfiction are one and the same as her powers as a writer of fiction. For her, both the essay and the novel can undo the work of individuation foisted upon us by modern society; they can bring “others” into contact and remind us of our common humanity.

Sometimes this larger project of humanization can show itself in the choice of a single word, like the solemn weight and subtle inflections of the adjective “educated” as it describes Paul D’s hands in Beloved as he and Sethe fumble toward the beginnings of a new life eked out within the living memory of enslavement. Other times it expresses itself in a lyrical outburst that captures a fleeting moment of self-fashioned freedom, a world of possibility momentarily gleaned from an otherwise desperate circumstance, as in this passage from Jazz:

Oh, the room—the music—the people leaning in doorways. This is the place where things pop. This is the market where gesture is all: a tongue’s lightning lick; a thumbnail grazing the split cheeks of a purple plum.

Finding those places where things pop is the central task of her humanism, which she calls, in the titular essay of the new collection, the act of “self-regard.” Self-regard, Morrison insists, is the process in which we recover our selves—in which we once again become human. It means experiencing black culture “from a viewpoint that precedes its appropriation”; it means seeing humanity after the veil of otherness has fallen. By stirring people into prideful expression, self-regard can help us see through the literalism and literal-mindedness that centuries of racist thought and practice that has prevented us from being better readers of our lives and, in turn, others’..."

--Jesse McCarthy--"The radical vision of Toni Morrison”, The Nation, December 16, 2019

Books of Literary Criticism by Toni Morrison:

PHOTO: Playing in the Dark by Toni Morrison, 1992

PHOTO: What Moves At The Margins by Toni Morrison, 2008

PHOTO: The Origins of Others by Toni Morrison, 2017

PHOTO: The Source of Self Regard by Toni Morrison, 2019

Angela Davis on Toni Morrison

August 8, 2019

August 8, 2019

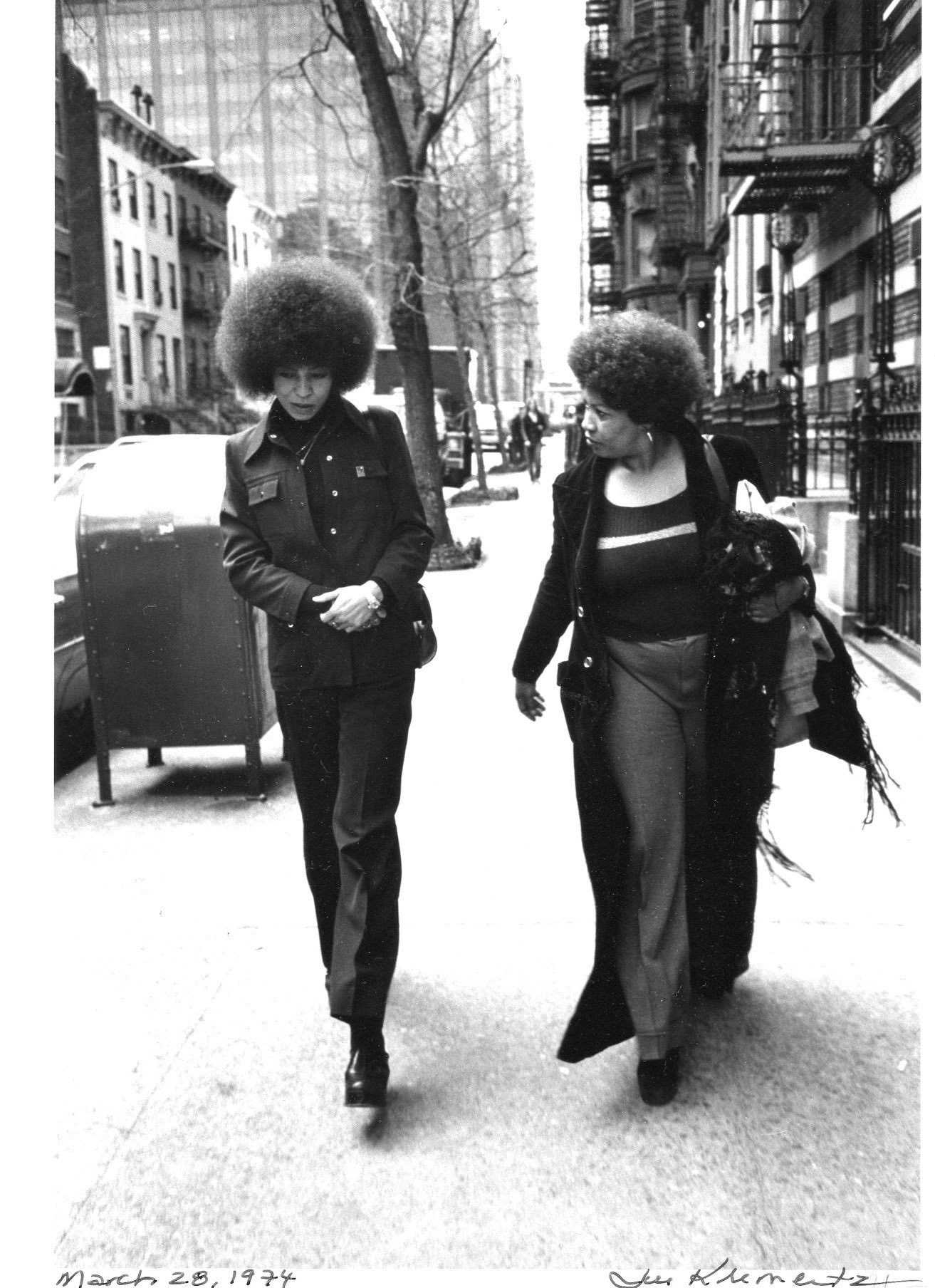

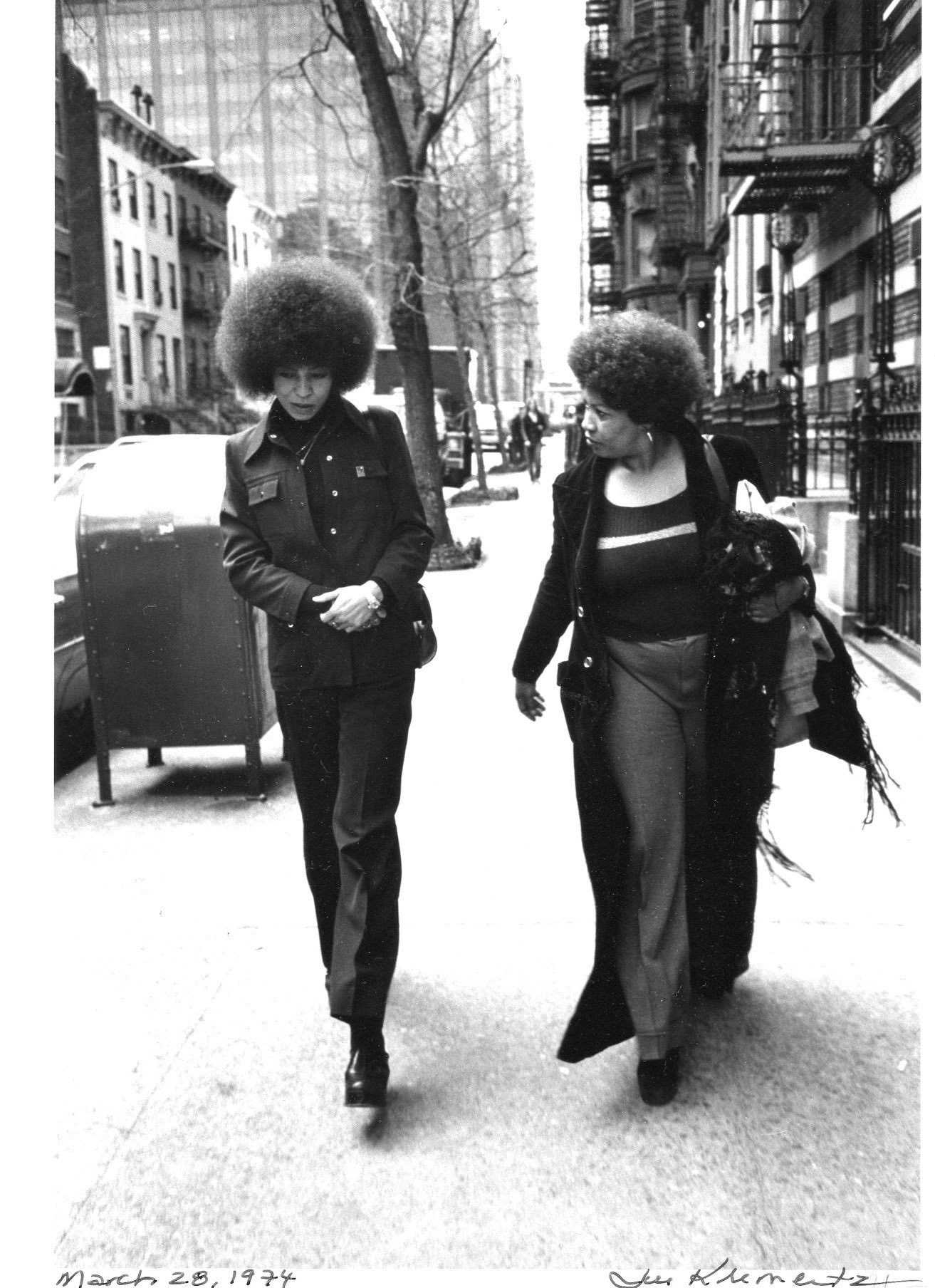

Amazing photo of Toni Morrison and Angela Davis, NYC, 1974.

Photo by Jill Krementz. All rights reserved.

As with all of our greatest thinkers, she held up a mirror that shows us our capacity for tremendous evil as well as for good. In one of her late novels, “A Mercy,” she returned us to a period before racial slavery was consolidated, when a new nation might have made a different set of choices and everything was in flux and possible. She does not take us down the path of the devastating choice that was made. We know that. We are living it. She simply uses the power of imagination to remind us that at any given stage, we might have chosen differently.

For her, the imagination is also a political resource. During the 2008 presidential campaign, she endorsed Barack Obama, expressing her admiration for his “creative imagination which coupled with brilliance equals wisdom.” Only that kind of wisdom might “help America realize the virtues it fancies about itself, what it desperately needs to become in the world.”

For her, the imagination is also a political resource. During the 2008 presidential campaign, she endorsed Barack Obama, expressing her admiration for his “creative imagination which coupled with brilliance equals wisdom.” Only that kind of wisdom might “help America realize the virtues it fancies about itself, what it desperately needs to become in the world.”

Toni was cleareyed about the United States, about the lies it tells itself, about the truth of its dark side and about its potential, rooted in its traditions of dissent, to offer a better future. A student of history, she understood that nations come and go, but that human beings had the capacity for change, evolution and growth, and that a more just world awaits if only we would commit to bringing it into being.

In her presence, whether on the page or in person, we understood the world was large and it was ours, to enter, to comment upon, to write about, to shape, mold and change. In her presence her brilliance was as apparent as it was capacious and inviting. She did not condescend to her readers or her friends; she was utterly confident of her own capacity and of ours.

All of us who were touched by her and all of those who are encouraged by her model to continue the good fight, are equipped with the tools she bequeathed us and challenged by her insistence that we cannot really be free unless we “free somebody else.”

In her presence, whether on the page or in person, we understood the world was large and it was ours, to enter, to comment upon, to write about, to shape, mold and change. In her presence her brilliance was as apparent as it was capacious and inviting. She did not condescend to her readers or her friends; she was utterly confident of her own capacity and of ours.

All of us who were touched by her and all of those who are encouraged by her model to continue the good fight, are equipped with the tools she bequeathed us and challenged by her insistence that we cannot really be free unless we “free somebody else.”

We will always treasure the miraculous gift of her friendship. And as we say goodbye, we hear her devilish laughter echoing around the universe.