Dori J. Maynard, Who Sought Diversity in Journalism, Dies at 56

By MARGALIT FOX

FEBRUARY 25, 2015

New York Times

All,

The shocking and tragic early death of Dori Maynard at the age of 56 from lung cancer is yet another MAJOR LOSS for black people in this country and for American journalism in general. Like her beloved father the legendary journalist, editor, and publisher Robert Maynard (1937-1993) who also died at 56, Ms. Maynard was one of the leading and most effective figures in the United States in the ongoing struggle for genuine racial equality and diversity in U.S. print and electronic media, as well as one of major leaders in the fight for true independence and self determination for African American journalists, editors, and publishers in the industry. To say that this visionary GIANT is going to be greatly missed is a huge understatement. To lose someone of Dori's intellectual, spiritual, and professional depth, clarity, strength, and passionate commitment at so early an age is simply overwhelming and another disturbing indication that we are presently losing major black leadership and creative talent in a wide range of fields generally at an alarming rate in this relentlessly cruel and debased society.

Our hearts and deep condolences go out to the Maynard family in their time of grief. RIP Ms. Maynard. We will deeply miss you and your inspiring pioneering work.

Kofi

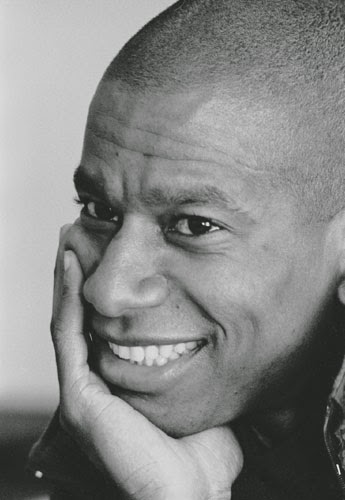

Dori J. Maynard speaking in 2013 at a public forum about the trial of George Zimmerman. Credit Jane Tyska/Bay Area News Group

Dori J. Maynard, a journalist who was at the forefront of the campaign to make the American news media a more accurate mirror of American diversity, died on Tuesday at her home in Oakland, Calif. She was 56.

The cause was lung cancer, her mother, Liz Rosen, said.

At her death, Ms. Maynard was the president and chief executive of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, a nonprofit organization based in Oakland and named for her father, a former editor and publisher of The Oakland Tribune. Mr. Maynard, who died in 1993, was the first black person in the United States to own a general-circulation daily newspaper.

A former newspaper reporter, Ms. Maynard joined the Maynard Institute not long after her father’s death and became its president in 2001.

There, she continued her lifelong interest in exploring the often rocky landscape where race, class, ethnicity and the news media converge. She lectured frequently on the subject and contributed articles to The Huffington Post, American Journalism Review and other publications.

During Ms. Maynard’s tenure, the institute’s purview included professional development, recruitment, a media watchdog program and a news service, America’s Wire, which provides articles on racial inequity and related subjects to newspapers, magazines and websites. To date, the institute has trained more than 5,000 minority journalists and newsroom managers around the country.

Dolores Judith Maynard was born in Manhattan on May 4, 1958; her parents divorced when she was 5. Her father’s second wife, Nancy Hicks Maynard, was one of the first black women to work as a reporter at The New York Times.

With colleagues, Robert and Nancy Maynard founded the Maynard Institute, originally known as the Institute for Journalism Education, in 1977; after Mr. Maynard’s death, it was renamed in his honor.

Dori Maynard earned a bachelor’s degree in American history from Middlebury College in Vermont and was later a reporter at The Bakersfield Californian; The Patriot Ledger, in Quincy, Mass.; and The Detroit Free Press, where her beats included City Hall and the coverage of poverty.

She and Mr. Maynard became the first father-daughter pair to be named Nieman fellows in journalism at Harvard, he in 1966 and she in 1993. Ms. Maynard was also a fellow of the Society of Professional Journalists.

With her father, she was the author of “Letters to My Children” (1995), a collection of his newspaper columns, for which she wrote introductory essays.

Ms. Maynard’s husband, Charles Grant Lewis, whom she married in 2006, died in 2008. Besides her mother, survivors include two brothers, David and Alex Maynard, and a sister, Sara-Ann Rosen. Her stepmother, Nancy Hicks Maynard, died in 2008.

Under Ms. Maynard’s stewardship, the Maynard Institute sought to educate not only aspiring journalists but also the profession of journalism itself, prodding news organizations to cast a wider net when it came to subjects deemed worthy of coverage.

“The conversation that goes on in the newsroom,” Ms. Maynard told NPR in 2005, “determines not only what stories get into the newspaper or onto your television or radio shows, but also determines all the elements that go into those stories.” She added:

“If that conversation is not managed in a way that allows the diversity of opinion that may be in your newsroom to be reflected in your coverage, important elements of those stories are left out, so that they become not only less relevant to communities of color, but they also shortchange the white community, because they are not finding out what’s going on in neighborhoods and communities other than their own.”

Dori

J. Maynard of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education,

left, speaks during a forum at Preservation Park's Nile Hall in

Oakland, Calif., on Thursday, July 18, 2013. To the right is Arnold

Perkins, of the Alameda County Public Health Department.

OAKLAND -- Dori J. Maynard, a journalist and longtime champion of diversity in news coverage and among the people who report the news, died Tuesday at her West Oakland home, friends and family said.

Maynard was 56. The cause of her death was complications from lung cancer.

"Dori was an amazing force for good in journalism," said Dawn Garcia, managing director of the Knight Fellowships at Stanford University. "She was the voice that must be heard.

"When others were shying away from speaking about race, Dori was fearless. She made an amazing difference for so many people and was just a fabulous person, quirky in the best sense of the word. She will be remembered in every newsroom where journalists are trying to make a difference for diversity and for equity in coverage."

The Oakland Tribune and the Maynard Institute held the free public forum to discuss coverage of the Zimmerman trial and how media images impact perception. (Jane Tyska/Bay Area News Group) ( JANE TYSKA )

The daughter of trailblazing Publisher Robert C. Maynard, the former owner of the Oakland Tribune and the first African-American man to own a major U.S. newspaper, Dori Maynard knew from an early age she, too, wanted to be a journalist, her mother Liz Rosen said Tuesday.

Once asked what her middle initial "J" stood for, she quipped: "Journalism." After graduating from Middlebury College in Vermont with a bachelor's degree in American history, she went on to work at the Detroit Free Press, the Bakersfield Californian, and The Patriot Ledger, in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Along with her father, she was a Nieman fellow at Harvard University in 1993. She found her calling at the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, founded by her father and his wife Nancy Hicks Maynard. Dori Maynard had served as president of the institute since 2001.

Before her death, she had overseen the institute's Fault Lines training program, which taught journalists to recognize their own blind spots when it came to covering the stories of diverse communities. She was on the Advisory Board of the Journalism and Women Symposium, a national group supporting women in journalism.

"She's the kind of person who understood how this idea of diversity was so vital today and continues to be vital and needed to change from our old ways of thinking of what that meant and how to implement it in the production of news and the way we think about news," said longtime friend Sally Lehrman. "She was always thinking about work because she loved it and it was such a part of her."

Martin Reynolds, community engagement editor for the Tribune, said Maynard was a mentor and friend, who kept a presence at the Tribune even after her father sold the paper. She was a key part of Oakland Voices, an outlet for residents to tell the stories they want to tell.

Maynard was a mentor to many young journalists, Reynolds and friends said.

"I don't know what I'm going to do without her," Reynolds said.

Bob Butler, president of the National Association of Black Journalists and a reporter at Bay Area radio station KCBS, said, "It's hard to fathom how the institute is going to go on, but it's got to go on."

In a statement posted to its site Tuesday, the institute said, "Maynard advocated tirelessly for the future of the institute and its programs, reminding all that the work of bringing the diverse voices of America into news and public discourse is more vital than ever.

"Under her leadership, the Institute has trained some of the top journalists in the country and helped newsrooms tell more inclusive and nuanced stories. New programs are empowering community members to voice the narrative of their own lives. On the morning of her death, she was discussing plans with a board member to help the institute thrive and to attract funding to support that work."

Funeral services for Maynard are still being planned.

Staff writer Karina Ioffee contributed to this report. David DeBolt covers breaking news. Contact him at 510-208-6453. Follow him at Twitter.com/daviddebolt.

Dori

J. Maynard, of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism

Education, speaks during a forum at Preservation Park's Nile Hall in

Oakland, Calif., in 2013.

'Her Calling Was To Help People Understand One Another': Remembering Dori Maynard

February 25, 2015

by Kenya Downs

Code Switch--NPR

In a heartfelt tribute, Fusion Voice's deputy editor Latoya Peterson recalled her seven-year relationship with journalist Dori Maynard as one of "an advisor, a mentor, and a beloved friend." Maynard, president of the Robert C. Maynard institute for Journalism Education, died Tuesday night at her home in Oakland, Calif. She was 56.

Peterson, a prominent feminist activist who runs the popular blog Racialicious, wrote that while Maynard's accomplishments are endless, it's her lasting impact on diversity initiatives in the newsroom that is most notable:

"It isn't enough to say that Dori was a tireless champion for diversity. Her calling in life was to help people understand one other. She never minimized the role of race in society, and courageously brought the subject up again and again. She countered every excuse she could find, always holding journalism to a higher standard, to truly represent the people of the United States of America. She often stressed [that] the path to accuracy and fairness in journalism required a commitment to broadening the ranks of the press corps."

She argues that more than ever, we need to heed Maynard's fierce insistence that the journalism industry should reflect the diversity of the world it covers:

"Dori knew that changing the tone, tenor, and composition of newsrooms was key to advancing racial justice across the nation. As long as the news peddled in stereotypical and discriminatory imagery, as long as it played a role in stoking the fear and mistrust of nonwhite citizens, our nation could never be whole."

Peterson continued her tribute online, where she cautioned young journalists to appreciate the mentors helping them find their voice.

Racialicious founder Latoya Peterson has a tearjerker of a tribute to journalism diversity pioneer Dori Maynard.npr.org

It's Time to Recognize All Dads on Father's Day

Send by email

Dori Maynard

June 13, 2013

Dear Sheryl Sandberg,

You advise women to lean in and speak up. I’m taking your advice.

I can’t tell you how disappointed I was in the Father’s Day feature on

which your Lean In Foundation collaborated with Time magazine. Not one

African-American father appears on the Time website. I know it shouldn’t

have shocked me.

Content audits, such as one by The Opportunity

Agenda, tell us that even in the age of President Obama, the media

continue to pigeonhole black men, consigning them to coverage about

crime, sports and entertainment, out of proportion with their actual

involvement. Equally important, the media rarely show black men in all

of their humanity as doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, politicians, and

yes, fathers.

Sadly, this feature is a stark example of the gap

between coverage and reality, and not just because it ignores black

fathers. There were also no Asian-American or Native American fathers in

Time. I note that the magazine did a good job of presenting a cross

section of white and Latino fathers.

Unfortunately, the other dads of color— one black and the other Asian-American — are relegated to your foundation’s website.

The problem with portraying such a narrow slice of fatherhood is threefold.

My first reaction on reading the list of fathers was, “Oh, no.” This is

why I don’t read Time very often. It’s not that I don’t like Time; it’s

just that it’s rarely relevant to my life. In today’s world, I don’t

think any publication wants to so visually remind potential readers why

they don’t read it.

I wasn’t alone. A quick look at the comments section finds others also clearly disappointed.

A commenter identifying herself as Claire Rodman wrote:

“TIME, it's been said, but it's worth saying again: There are plenty of

black dads with daughters, and famous ones to boot: Mr. Poitier, Mr.

Cosby, Denzel Washington, etc. Did you think we were all raised by

single mothers? A lost opportunity, and likely some lost

subscribers/online readers.”

The second problem is inaccuracy. As

Rodman and other commenters noted, there are plenty of prominent

African-American fathers. The same is true of Asian-American and Native

American men with daughters. Yo-Yo Ma and Ben Nighthorse Campbell, the

Senate’s first Native American, come to mind. Not including the wide

range of fathers in this country perpetuates false stereotypes and gives

readers a misleading sense of how their neighbors live and interact

with family.

That brings us to the third reason. We’re in the

business of giving the public credible, reliable information. A feature

suggesting that only some men participate in raising daughters fails to

meet our ethical and moral standards.

For those who question the

necessity of diversity, this should be a reminder that having people

with different perspectives in the room can help us see what we are

missing. In 2011, Richard Prince, a columnist for the Maynard Institute

for Journalism Education, noted that Time magazine was losing its only

black correspondent.

That loss increased the chance that no one

at Time would flag the omissions. All of us need someone to prod us

because it is so easy for us to fall in with people who reinforce our

world view. It’s called homophily, otherwise known as “birds of a

feather” or “love of the same.” I work in diversity every day and still

find that I must push myself not to make that same mistake.

Nevertheless, I sometimes do.

I have also developed a diverse

network of people willing to call me on mistakes so I can fix them.

That’s really why I’m writing to you. The beauty of online features

means that they can easily and quickly be fixed.

Sheryl, it’s not

too late to remedy this by reminding African-American, Asian-American

and Native American girls that they, too, have fathers who love them and

are worth noting.

Sincerely,

Dori Maynard

Dori J. Maynard

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dori J. Maynard, 2008

Born May 4, 1958

Died February 24, 2015

Education Middlebury College; Nieman Fellow

Home town Oakland, CA

Title President and CEO

Spouse(s) Charles Grant Lewis, deceased

Website: http://www.mije.org

Dori J. Maynard (May 4, 1958 – February 24, 2015) was the President of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education in Oakland, California, the oldest organization dedicated to helping the nation's news media accurately and fairly portray all segments of our[who?] society. In its 33 year history,[when?] the Institute has trained thousands of journalists of color, including the national editor of the Washington Post, the editor of the Oakland Tribune and the only Latina[citation needed] to edit a major metropolitan newspaper. She was the co-author of "Letters to My Children," a compilation of nationally syndicated columns by her late father Robert C. Maynard, with introductory essays by Dori. She served on the board of the Sigma Delta Chi Foundation, as well as the Board of Visitors for the John S. Knight Fellowships.

Past experiences

As a reporter, she worked for the Bakersfield Californian, and The Patriot Ledger in Quincy, Massachusetts, and the Detroit Free Press. In 1993 she and her father became the first father-daughter duo ever to be appointed Nieman scholars at Harvard University; Bob Maynard won this fellowship in 1966.

She received the "Fellow of Society" award from the Society of Professional Journalists at the national convention in Seattle, Washington on October 6, 2001 and was voted one of the "10 Most Influential African Americans in the Bay Area" in 2004. In 2008 she received the Asian American Journalists Association’s Leadership in Diversity Award.

Maynard graduated from Middlebury College in Vermont with a BA in American History.

External links

www.mije.org

Dori on Diversity

Huffington Post

Robert C. Maynard: Life and Legacy

Robert C. Maynard

(1937-1993)

Robert C. Maynard, a charismatic leader who changed the face of American journalism, built a four-decade career on the cornerstones of editorial integrity, community involvement, improved education and the importance of the family.

He was the co-founder of the Institute for Journalism Education, a nonprofit corporation dedicated to expanding opportunities for minority journalists at the nation's newspapers. In the past 25 years, it has trained hundreds of America's journalists of color, more than any other organization. In December 1993, following Maynard's death, the Institute was renamed the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education.

In the 1980s, Maynard began a twice-weekly syndicated newspaper column, in which he transformed national and international issues into dinner table discussions of right and wrong. His views were widely broadcast through regular appearances on "This Week With David Brinkley" and the "MacNeil Lehrer Report."

He was a board member of the industry's most prestigious organizations, including the Pulitzer Prize, The Associated Press, and the American Society of Newspaper Editors. It was his lobbying in the 1970s that nudged the ASNE to adopt the goal of diversifying America's newsrooms by the year 2000.

"This country cannot be the country we want it to be if its story is told by only one group of citizens. Our goal is to give all Americans front door access to the truth," he said in May of 1993 during his last public address, to college students at The Freedom Forum, in Arlington, Va.

Robert C. Maynard: A Tribute

View the video about Bob Maynard which was shown at the Free Spirit Award Dinner, held at the Paramount Theater, in Oakland, Calif., on June 14, 1994.

In 1979, Maynard took over as editor of The Oakland Tribune, which just a few years earlier had been labeled "arguably the second worst newspaper in the United States." He bought the paper in 1983, taking the title of editor and president in the first management-leveraged buyout in U.S. newspaper history. By doing so, he became the first African American to own a major metropolitan newspaper.

After a decade of ownership by Bob and Nancy Maynard, the newspaper had won hundreds of awards for editorial excellence. One media critic described the change: "The Tribune covers the Oakland area with far more insight than do its wealthier competitors in nearby San Francisco and the suburbs, and the paper has become a kind of journalistic farm team for larger papers such as the Los Angeles Times. The Tribune won a Pulitzer Prize in 1990 for its coverage of the Loma Prieta earthquake, and its coverage of the Oakland Hills fire was nothing short of superb."

It was the earthquake and fire, combined with the national recession and a troubled city economy, that finally forced the Maynards to sell The Tribune in 1992.

When the paper was sold, its most valuable assets were its loyal readers and advertisers, its scrappy editorial product and the most diverse newsroom of any major metropolitan newspaper in America.

Robert C. Maynard standing in front of the Oakland Tribune, 1993

"The Maynards devoted a decade of their lives to saving the newspaper when no one else would. They brought journalistic excellence and diversity to the newspaper unmatched in its previous century of publication," wrote competitor Dean Singleton in December 1992 after the MediaNews group purchased The Tribune.

"Bob Maynard's journalistic talents and dedication are of course well known. But he does not get the plaudits he deserves for business acumen. It is doubtful that The Oakland Tribune would be alive today if not for Bob's keen ability to maneuver through economic mine fields day after day, year after year."

Maynard, the son of an immigrant from Barbados who founded a New York moving company, dropped out of a Brooklyn high school at the age of 16 to become a writer in Greenwich Village in the 1950s. He had a photographic memory, and mastered myriad subjects through reading and inquiry. Ultimately, he held eight honorary doctorates. "My credentials," he told a sister on the day he decided to quit school, "will be my work."

His early role models, writers Langston Hughes and Ernest Hemingway, later gave way to his hero, Dr. Martin Luther King. But he did not want people to follow his path away from formal education. "I say to young people today that they must stay in school," he wrote in a column. "Autodidacts, self teachers, are of another age, I tell them. School today is imperative. All the same, my adventures suited me and served me well. My sisters even agree, grudgingly."

Maynard was most proud of the Elijah Parish Lovejoy award he received from Colby College in Maine. The national honor is named for the owner of an abolitionist newspaper in Alton, Ill., who was killed by a pro-slavery mob in 1837.

"You have rallied employees in the face of uncertainty and citizens in the aftermath of disaster, fighting for the heart and soul of your adopted community the way Elijah Parish Lovejoy once did in his, with faith, nerve and a printing press," Colby President William R. Cotter said as he presented the award in November 1991.

Maynard's formula for community involvement was simple: Just do it. He taught at local high schools, attended community forums, organized relief for babies of cocaine-addicted mothers and for victims of the Loma Prieta earthquake and the East Bay hills firestorm, and helped establish youth forums in the city's churches in the aftermath of the Rodney King verdict. His newspaper crusaded for improved schools, trauma care centers, economic development and better communication across cultural lines. A newspaper, he wrote in 1979, in his first Letter from the Editor column, should be "an instrument of community understanding."

Robert C. Maynard, York Pennsylvania, USA

His journalism career began in 1961 at a daily newspaper in York, Pa. In 1965, he received a Nieman fellowship to Harvard University. In 1992, his daughter, journalist Dori J. Maynard, became the first woman to follow her father to Harvard as a Nieman scholar. After Harvard, Bob Maynard covered civil rights and urban unrest as a national correspondent for The Washington Post. He later became the newspaper's ombudsman, and later still, joined the staff of the editorial page.

It was in Washington, D.C., that he met his bride-to-be, then New York Times reporter Nancy Hicks. They were married in 1975.

Maynard was first diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1988. It went into remission twice, but returned a third time in 1992 and was a factor in the family's decision to sell the newspaper. Even through his illness, Maynard was the quintessential optimist.

"The country's greatest achievements came about because somebody believed in something, whether it was in a steam engine, an airplane or a space shuttle,'' he once wrote. "Only when we lose hope in great possibilities are we really doomed. Reversals and tough times inspire some people to work harder for what they believe in."

Robert C. Maynard

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Robert C. Maynard

Born Robert Clyve Maynard

June 17, 1937

Brooklyn, New York, U.S.

Died August 17, 1993 (aged 56)

Oakland, California, U.S.

Nationality American

Education Harvard University

Known for Journalist

Editor of Oakland Tribune

Maynard Institute co-founder

Notable credit(s) The Oakland Tribune

Spouse(s) Nancy Hicks Maynard (1975–1993)

Children Dori J., David and Alex

Robert Clyve Maynard (June 17, 1937 – August 17, 1993) was an American journalist, newspaper publisher and editor, former owner of The Oakland Tribune, and co-founder of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education in Oakland, California.

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 Early years

1.2 Career

1.3 Personal life

2 Bibliography

3 References

4 External links

Biography

Early years

Maynard was one of six children to Samuel C. Maynard and Robertine Isola Greaves, both immigrants from Barbados. At 16 years old, he dropped out of Brooklyn High School to pursue his passion for writing. Maynard became friends with influential New York writers James Baldwin and Langston Hughes and later acknowledged Martin Luther King, Jr. as a hero.

Career

Maynard's career in journalism began in 1961 at York Gazette & Daily in York, Pennsylvania. In 1966, he received a Nieman Fellowship to Harvard University and joined the editorial staff of the Washington Post the following year.

In 1979, Maynard took over as editor of The Oakland Tribune and became the first African American to own a major metropolitan newspaper after purchasing the paper four years later. He is widely recognized for turning around the then struggling newspaper and transforming it into a 1990 Pulitzer Prize-winning journal.

Maynard greatly valued community involvement. He taught at local high schools and frequently attended community forums. His positive, proactive outlook helped many in need, including children of cocaine-addicted mothers and earthquake and firestorm victims. Maynard used the outreach of his newspaper to better the community by pushing for improved schools, trauma care centers, and economic development.

The Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education

In 1977, Maynard co-founded the Institute for Journalism Education, a nonprofit organization dedicated to training journalists of color and providing accurate representation of minorities in the news media. For more than thirty years, the Institute has trained over 1,000 journalists and editors from multicultural backgrounds across the United States.

Personal life

The Institute he co-founded with his second wife Nancy Hicks Maynard (1947–2008) was renamed in his honor after his death from prostate cancer in 1993. His daughter, Dori J. Maynard, has since become president and CEO of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education.

Bibliography

Maynard, Robert C. (1968). Nationalism and Community Schools. Washington: The Brookings Institution. OCLC 80975022.

Maynard, Robert C. (1982). Ralph McGill's America and Mine. Athens: The University of Georgia. OCLC 11822319.

Maynard, Robert C. (1989). Earthquakes, Freedom and the Future. Tucson: The University of Arizona. OCLC 22919891.

Maynard, Robert C. (1989). Communication in the (Shrinking) Global Village. Bridgetown: Central Bank of Barbados. ISBN 976-602-035-3.

Maynard, Robert C. (1992). Reflections on the Post-Cold War Era. Honolulu: East-West Center. OCLC 34489231.

Maynard, Robert C.; Maynard, Dori J. (1995). Letters to My Children. Kansas City, MO: Andrews and McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-7027-4.

References

"Robert C. Maynard: Life and Legacy". Maynard Institute. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

Mark Kram (2008). "Black Biography: Robert Maynard". Contemporary Black Biography. The Gale Group. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

External links

Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education official website

Robert C. Maynard at the African American Registry (archived by the Wayback Machine