‘Stoolpigeons’ and the Treacherous Terrain of Freedom Fighting

By Charisse Burden-Stelly

September 13, 2018

On May 15, 2018, Newsweek published a story entitled, “CIA Reveals Name of Former Spy in JFK Files—And He’s Still Alive.” In it, Richard T. Gibson was identified as a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operative from 1965 to 1977. An exposé published a day after the Newsweek story, “What the Curious Case of Richard Gibson Tells Us About Lee Harvey Oswald,” reported that in 1962 Gibson resigned from the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC)—an organization he co-founded with Robert Taber in 1960—and offered his services to the CIA. An earlier article, “The Ghosts of November,” written by Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan in 1994 and updated in 2001, included New Jersey FPCC member Hal Verb’s claim that members suspected Gibson of being a “stoolpigeon” very early on. When the authors presented him with evidence, including a letter released by the CIA that asked a commercial company to place Gibson on retainer on its behalf, he responded that it “sounded like” disinformation.

Indeed, Gibson has consistently denied allegations of cooperation with the government for several decades. In “Richard Wright’s ‘Island of Hallucination’ and the Gibson Affair,” for example, he wrote that he received a substantial award in a lawsuit against Penguin Books when Gordon Winter accused him of being a CIA agent, an agent provocateur, and a traitor. Likewise, a footnote in Chris Tinson’s Radical Intellect: Liberator Magazine and Black Activism in the 1960s explains that when the author asked Gibson about these allegations, he denied them and noted that he had won a libel case against persons who made such claims. Despite these denials, a multitude of documents are available that corroborate Gibson’s involvement with the CIA. This raises a number of interesting questions.

First, even as prominent figures including E. Franklin Frazier, Julian Mayfield, and Richard Wright raised suspicion about Gibson’s affiliations as early as 1959, activists such as Robert F. Williams, Max Stanford, and Vusumzi Make (former husband of Maya Angelou) purportedly defended him against these charges, at least through 1966.1 Why were Gibson’s nefarious affiliations blatantly obvious to some, but inconceivable to others?

Second, Gibson carried on a very long correspondence with Hodee Edwards, a Jewish woman married to an African American ex-patriate living in Ghana, throughout the 1960s. He had not met her in person at the time they became pen pals. Though Edwards had worked for one of Kwame Nkrumah’s closest allies, John Tettegah, she too had been accused of being an agent, not least by Shirley Graham Du Bois, who had warned Nkrumah that something was amiss with her shortly before the February 24, 1966 coup.2 Were Edwards and Gibson “birds of a feather,” both working to destabilize Black leftist liberation movements?

Third, Mayfield claimed that Gibson predicted events that transpired in Algeria that year—namely, the overthrow of Ahmed Ben Bella on June 19, 1965. This “sinister” revelation piqued Mayfield’s suspicion. Interestingly, the day of the coup Gibson was heading to Algeria from Morocco. He took handwritten notes over the next five days about the “Council of Revolution” that had ousted Ben Bella. These included denunciations of the former leader, notes about whether the Second Afro-Asian conference would still be held in Algiers, and information about various countries’ support of the new regime. Further, Gibson did not hide his disdain for Ben Bella before or after the coup. In 1965, he wrote, “Frankly, I never liked the man, considered him essentially weak, always ready to make every sort of promise under pressure, promises which he could not keep, lacking objectives and whose ‘leftism’ was mainly cheap demagogy.” He also expressed support for Ben Bella’s ouster and for Houari Boumédiène, and attempted to sell his article about the “true” nature of what had transpired in the “June 19 movement” to a number of progressive and leftist newspapers and magazines.3 Is it significant that Gibson, who had nothing but disdain for Ben Bella, was in close proximity to Algeria at the time of the coup?

The Richard T. Gibson Papers provide little in the way of direct confessions. In fact, quite the opposite is true. Throughout his correspondence from 1964 onward, Gibson deflects, denies, and ridicules the idea that he is a CIA operative though the allegations are numerous and persistent. Nonetheless, the archive provides a wealth of information about and insight into his tactics of concealment, evasion, and misdirection. In particular, he masterfully employs dominant discourses of Black Power, Third Worldism, and Tricontinentalism years before they became mainstream. The “Third World” as a political orientation was an internationalist formation that included all non-white oppressed persons who shared a common struggle, a common vision, and a common enemy: white Western imperialist society. It included those whose subjection was not ameliorated by the nominal gains of bourgeois civil rights and independence movements—the revolutionary masses, the superexploited proletariat, and militants engaged in urban rebellion and guerilla warfare.

Third Worldism was a historical development at the conjuncture of post-World War II global transformations, the Cold War, the ascendance of United States military and economic hegemony, and the insurgency of racialized, colonized, and oppressed peoples against Euro-American geopolitics. It was a theoretical position and discursive formation centered on anti-imperialism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism, and anti-capitalism. It was also a cultural and political enunciation of de-territorialized solidarity. In short, it offered a “third way” between the imposition of Euro-American capitalism and Soviet Union-style communism.

Gibson capitalized on the Sino-Soviet split, the popularity of Maoism, and the construction of African Americans as the vanguard of the revolution in the “belly of the beast” to discredit and cast doubt upon individuals, organizations, and nations that were integral to Third Worldism. He accused the Cubans of racism, revisionism, and genuflection to Moscow to explain why he was barred from the 1966 Tricontinental Conference. He condemned the non-violence of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to encourage more “revolutionary” action in a possible attempt to steer the organization on a path that would invite government imposition. He also claimed that all those who questioned his affiliations were themselves tools of the CIA, imperialism, Trotskyism, or revisionism.4 These attempts at disparagement were meant to—and often did—invite dissent, disarray, surveillance, and violence. Moreover, Gibson accused those who disassociated from him because of his suspected CIA links of “McCarthyite behavior” and “witch hunts” to cajole them into “stat[ing] as fully as possible the nature and the details of the accusations made against [him] and… by whom they [were] made.” In other words, he promoted suspicion as a form of intelligence gathering. He also used that language, along with the fact that he had been “twice subpoenaed before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee of the U.S. Congress” to legitimate his “leftist” credentials.5

African Americans like Richard Gibson, Julia Clarice Brown, and Lola Belle Holmes who supplied government agencies with a multitude of information about Black and Third World radical movements, organizations, and activism reveal the treacherous terrain freedom fighters were forced to navigate. These “stoolpigeons,” “turncoats,” and career informants made monumental challenges to racism, imperialism, colonialism, and capitalist exploitation all the more dangerous and difficult. The reality that “all skin ain’t kin” notwithstanding, one wonders how successful liberation struggle could have been without these persistent destabilization efforts.

- See e.g., Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 24 October 1965; Richard Gibson to Hodee Edwards, 15 October 1966, Richard T. Gibson Papers (MS 2302), Special Collections Research Center, George Washington University (Gibson Papers hereafter). ↩

- Richard Gibson to Lionel (Morrison), 12 January 1966; Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 27 May 1965; Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 9 June 1966, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

- Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 24 October 1965; “19 June,” n.d.; Richard Gibson to Marc Abdalla Schleifer, 14 November 1965; Richard Gibson to Hodee Edwards, 2 November 1965; Richard Gibson to Hodee Edwards, 2 October 1965, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

- See e.g., Richard Gibson to Sheila Patterson Horko, 14 January 1966; Richard Gibson to “Betita” (Elizabeth Martinez Sutherland), 28 July 1965; Richard Gibson to Mr. Leopoldo Leon, 20 June 1966, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

- Richard Gibson to Mr. Leopoldo Leon, 20 June 1966, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

https://www.newsweek.com/richard-gibson-cia-spies-james-baldwin-amiri-baraka-richard-wright-cuba-926428

Newsweek Magazine

CIA Reveals Name of Former Spy in JFK Files—And He's Still Alive

by Jefferson Morley

May 15, 2018

Newsweek

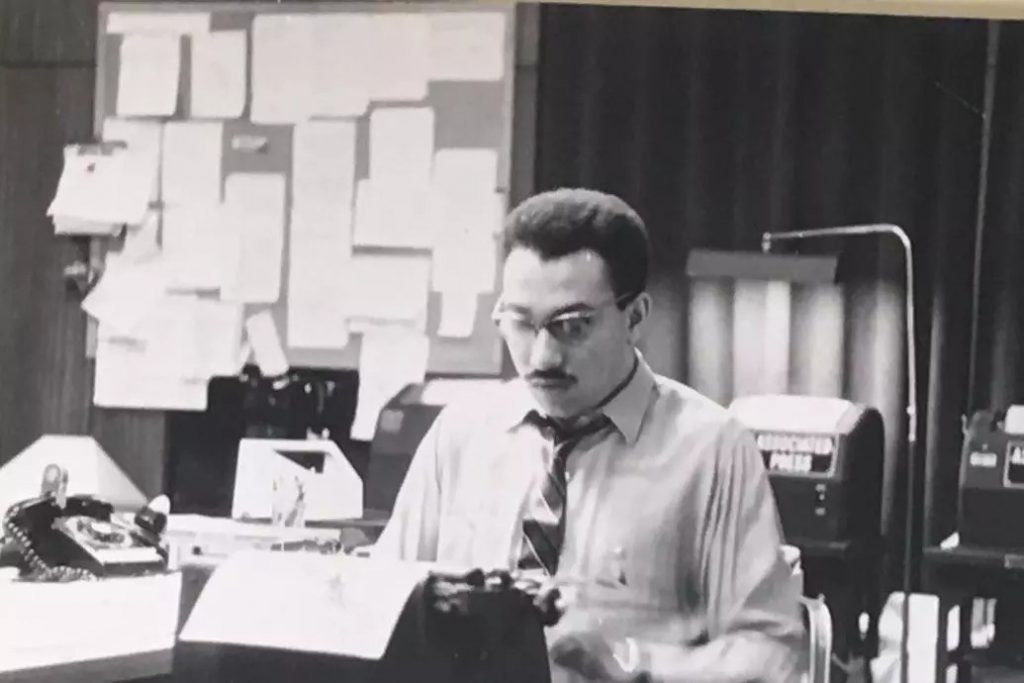

PHOTO: Richard Gibson working as a journalist for CBS Radio News. Richard T. Gibson Papers/George Washington University

Updated | In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Paris beckoned African-American intellectuals hoping to escape the racism and conformity of American life. Chief among them: Richard Wright, the acclaimed author of Native Son and Black Boy, who arrived in 1947. He was soon joined by Chester Himes, an ex-convict who mastered hard-boiled detective fiction; James Baldwin, the precocious essayist; and Richard Gibson, an editor at the Agence France-Presse.

These men became friends, colleagues and, soon, bitter rivals. Their relationship appeared to unravel over France’s war to keep its colony in Algeria. Gibson pressured Wright to publicly criticize the French government, angering the acclaimed author. Wright dramatized their falling-out in a roman à clef he called Island of Hallucination, which was never published, even after his death in 1960. In 2005, Gibson published a memoir in a scholarly journal recounting the political machinations his former friend had dramatized, telling The Guardian he had obtained a copy of the manuscript and had no objections to its publication. “I turn up as Bill Hart, the ‘superspy,’” Gibson said of the story.

Wright’s book now seems prescient. In a strange twist, on April 26, when the National Archives released thousands of documents pertaining to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, they included three fat CIA files on Gibson. According to these documents, he had served U.S. intelligence from 1965 until at least 1977. This was well after Wright wrote his book, and it’s not clear if Gibson had engaged in espionage before that period. But his files revealed his CIA code name, QRPHONE-1; his salary (as much as $900 a month); and his various missions, as well as his attitude (“energetic”) and performance (“a self-starter”).

The most curious part of the story: Gibson is still alive. He’s 87 and living abroad. (Gibson “will not be able to your questions,” said a family friend who answered the phone at his residence.)

The CIA is usually vigilant about defending the confidentiality of its sources and methods. In announcing the release of the JFK files last year, President Donald Trump declared the records would be opened in their entirety, “except for the names and addresses of living persons.” Save for Gibson’s, apparently. (The CIA declined to comment for this story.)

Born in 1931, Gibson grew up in Philadelphia and attended Kenyon College in Ohio. A stint in the Army gave him a taste for European life, and he moved to Rome and then to Paris. He wrote a novel, a detective story called A Mirror for Magistrates, and fell in and out with Wright and other expatriate intellectuals.

In 1957, Gibson left Paris and went to work for CBS Radio News, according to his newspaper reports. With a colleague, he covered the Cuban revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. In 1960, Gibson, who then sympathized with leftist movements, co-founded the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), which defended Castro’s government from negative coverage in the North American press.

When he left CBS, Gibson took over running the FPCC, and it grew rapidly on college campuses. He resisted subpoenas from Senate investigators seeking to discredit the group and urged civil rights leaders to support the Cuban cause.

Yet in July 1962, Gibson quit the FPCC and wrote an anonymous letter on the group’s stationery to the CIA. If the agency would arrange a secure meeting spot, he wrote, he could be of assistance.

The CIA figured out who wrote the letter and made contact with the young intellectual. He had moved on to Switzerland to become the English-language editor of a new magazine called La Révolution Africaine. In a January 1963 memo, CIA Deputy Director Richard Helms informed the FBI that Gibson had told an agency source about the ideological direction of the magazine—further left—and how it planned to relocate 15 staff members from Paris to Algiers.

When Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, the CIA asked Gibson about accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, who had corresponded with the FPCC. Gibson told them what little he knew and indicated he wanted to “maintain contact” with the U.S. government.

In the summer of 1964, Gibson had another falling-out, this time with the publisher of La Révolution Africaine, who accused him of being an agent of the FBI and CIA. Whenever the charge was repeated years later, Gibson shrugged it off. “If I’m CIA, where’s my pension?” he told The Guardian in 2006.

By then, Gibson was no longer working for the agency. But his file shows that a Langley officer contacted him in January 1965 and arranged for a debriefing and “test assignment” that summer: “After recruitment and agreement to...[polygraph] examination, [s]ubject was introduced to his…case officer.” He soon began working for the intelligence service as a spy.

Four years later, according to his file, the agency increased Gibson’s tax-free salary of $600 a month to $900 a month (the equivalent of more than $6,000 in 2018 dollars). His mission: to report on “his extensive contacts among leftist, radical, and communist movements in Europe and Africa.”

Related Stories:

New Study Debunks JFK Conspiracy Theory

Trump's Twitter Fingers on the Grassy Knoll

The CIA's Secrets About JFK, Che, and Castro Revealed

Gibson, his wife and their two kids settled in Belgium, where he lived the life of a cosmopolitan intellectual. He traveled widely and wrote a book about African liberation movements fighting white-minority rule. He also monitored the revolutionary poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, who trusted him as an ideological comrade. In his letters to the CIA’s spy, Baraka signed off with the valediction “In struggle.” (Baraka’s son, Ras, is the mayor of Newark, New Jersey.)

While the newly released CIA files don’t include operational details, Gibson seems to have been a prolific spy. One CIA memo asserts that in 1977 his file contained more than 400 documents.

His quip to The Guardian notwithstanding, Gibson even had a CIA pension of sorts. In September 1969, his case officer noted that “QRPHONE/1 has begun to invest a portion of his monthly salary in a reputable mutual fund of his choice. This modest investment program will enhance financial security in the event of termination and/or a rainy day.”

Gibson was still an “active agent” in 1977 when Congress reopened the JFK investigation and started asking questions about the agency’s penetration of the FPCC in 1963. The House Select Committee on Assassinations asked to see Gibson’s CIA file. The agency showed investigators only a small portion of it, but the entirety of the still-classified material became part of the CIA’s archive of JFK records.

That designation would eventually change. In October 1992, Congress passed a law mandating the release of all JFK files within 25 years. Gibson’s secret was safe for the time being. In 1985, he successfully sued a South African author who asserted he was a CIA agent. The book was withdrawn, and the publisher issued a statement declaring that “Mr. Gibson has never worked for the United States Central Intelligence Agency,” a claim that no longer seems tenable.

In 2013, Gibson sold his collected papers to George Washington University in Washington, D.C. To celebrate the acquisition, the university held a daylong symposium, “Richard Gibson: Literary Contrarian & Cold Warrior,” dedicated to “furthering our understanding of the intellectual and literary history of the Cold War.”

With the release of Gibson’s CIA files, scholars can now discern the hidden hand of the American clandestine service in writing that history. When it came to the character who inspired Bill Hart, “the superspy,” Richard Wright’s fiction was perhaps ahead of its time.

This story has been updated with additional context to reflect the version that appears in the June 1 print edition of Newsweek.