“Canon formation is necessarily skewed. It’s necessarily racist and sexist. As soon as you’re saying there are these texts that must be read, someone has to choose. Who chooses?...Whoever controls language, controls everything. If someone has no voice, they cannot get what they want or what they need. Any work of art that comes out of this American culture is about race. If there is no race in it, that is a statement about race…"

–Percival Everett

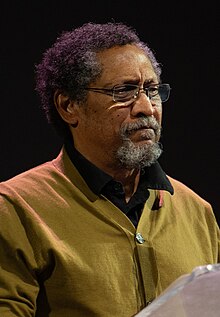

Percival Everett Is Challenging the American Literary Canon

by Eliana Dockterman

February 6, 2025

TIME

Percival Everett claims he is not as brilliant as his fans know him to be. He deeply researches the worlds in which his novels are set, yet swears that everything he learns falls out of his head as soon as each book is published. “So I’m no smarter at the end than I was at the beginning,” he says, shrugging his shoulders. Years ago, sick of his writing students asking him if they were good enough to be published, he took a class to a bookstore in Middlebury, Vt., to prove he was not unique. “Look around,” he told them. “Anyone can be published. ‘Are you good enough to make a difference?’ is the question.”

With his latest, James, a reimagining of Huckleberry Finn told from the perspective of the escaped slave Jim—who drops his nickname for the more noble-sounding James—Everett has jump-started a conversation about the great American novel, how issues of race interplay with the so-called American canon, and how we talk to our children about America’s past. But just a few hours before he wins the National Book Award for fiction, he demurs when pressed on the book’s impact. “If a reader is coming to me for any kind of message or answer about anything in the world,” he says, “they’re already in deep trouble.”

For many, however, James has become an important companion piece to Mark Twain’s work, the book “all American literature comes from,” to quote Ernest Hemingway. “I’ve been getting lots of mail from former and current English teachers thanking me that they can now teach Huck Finn again because they can do it alongside James,” he admits, “which is great news for me and certainly flattering, but doesn’t come as a great surprise. It’s a problematic text.”

Everett, 68, would do away with the canon altogether if he could. But at the very least he hopes that writers, readers, and educators can acknowledge the inherent issues with putting certain books on a pedestal. “My joke is, ‘The canon is loaded,’” says Everett. “Canon formation is necessarily skewed. It’s necessarily racist and sexist. As soon as you’re saying there are these texts that must be read, someone has to choose. Who chooses?”

While Jim is little more than a sidekick on Huck’s journey down the Mississippi in the original, in Everett’s version he is at the center of the story. James and other Black characters code switch when white characters are present; on his own, James interrogates philosophers like Voltaire for his repugnant views on slavery. “Enslaved people, it had occurred to me, are always depicted as simple-minded and superstitious, and of course, they weren’t,” Everett says. “So I embarked on this.”

Everett gives James the gift of language, and James writes his account of his travels with a stolen pencil stub—one which comes at great human cost. “Whoever controls language, controls everything. If someone has no voice, they cannot get what they want or what they need,” says Everett.

Everett, who has published two dozen novels, including the Pulitzer Prize finalist Telephone, has historically bristled at being categorized in the genre of African American fiction, especially considering he has written everything from propulsive westerns to a novella styled like a Lifetime movie. “Any work of art that comes out of this American culture is about race. If there is no race in it, that is a statement about race,” he says.

This frustration is at the heart of Erasure, one of Everett’s early and best-known novels, which was adapted into the Oscar-winning 2023 film American Fiction. The story centers on Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, the author of experimental novels that don’t sell particularly well. Monk becomes so exasperated with the publishing industry bolstering Black fiction that depicts only stereotypes that he pens a novel as an illiterate thug to prove a point. The book is a hit, much to the author’s chagrin. James, too, will get the Hollywood treatment, with Steven Spielberg producing and Taika Waititi in talks to direct, though Everett insists this attention is “fleeting.” “I'll write some experimental novel next that no one will understand,” he says. “You would have to be crazy to get into literary fiction to get famous or to get rich.”

With his latest, James, a reimagining of Huckleberry Finn told from the perspective of the escaped slave Jim—who drops his nickname for the more noble-sounding James—Everett has jump-started a conversation about the great American novel, how issues of race interplay with the so-called American canon, and how we talk to our children about America’s past. But just a few hours before he wins the National Book Award for fiction, he demurs when pressed on the book’s impact. “If a reader is coming to me for any kind of message or answer about anything in the world,” he says, “they’re already in deep trouble.”

For many, however, James has become an important companion piece to Mark Twain’s work, the book “all American literature comes from,” to quote Ernest Hemingway. “I’ve been getting lots of mail from former and current English teachers thanking me that they can now teach Huck Finn again because they can do it alongside James,” he admits, “which is great news for me and certainly flattering, but doesn’t come as a great surprise. It’s a problematic text.”

Everett, 68, would do away with the canon altogether if he could. But at the very least he hopes that writers, readers, and educators can acknowledge the inherent issues with putting certain books on a pedestal. “My joke is, ‘The canon is loaded,’” says Everett. “Canon formation is necessarily skewed. It’s necessarily racist and sexist. As soon as you’re saying there are these texts that must be read, someone has to choose. Who chooses?”

While Jim is little more than a sidekick on Huck’s journey down the Mississippi in the original, in Everett’s version he is at the center of the story. James and other Black characters code switch when white characters are present; on his own, James interrogates philosophers like Voltaire for his repugnant views on slavery. “Enslaved people, it had occurred to me, are always depicted as simple-minded and superstitious, and of course, they weren’t,” Everett says. “So I embarked on this.”

Everett gives James the gift of language, and James writes his account of his travels with a stolen pencil stub—one which comes at great human cost. “Whoever controls language, controls everything. If someone has no voice, they cannot get what they want or what they need,” says Everett.

Everett, who has published two dozen novels, including the Pulitzer Prize finalist Telephone, has historically bristled at being categorized in the genre of African American fiction, especially considering he has written everything from propulsive westerns to a novella styled like a Lifetime movie. “Any work of art that comes out of this American culture is about race. If there is no race in it, that is a statement about race,” he says.

This frustration is at the heart of Erasure, one of Everett’s early and best-known novels, which was adapted into the Oscar-winning 2023 film American Fiction. The story centers on Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, the author of experimental novels that don’t sell particularly well. Monk becomes so exasperated with the publishing industry bolstering Black fiction that depicts only stereotypes that he pens a novel as an illiterate thug to prove a point. The book is a hit, much to the author’s chagrin. James, too, will get the Hollywood treatment, with Steven Spielberg producing and Taika Waititi in talks to direct, though Everett insists this attention is “fleeting.” “I'll write some experimental novel next that no one will understand,” he says. “You would have to be crazy to get into literary fiction to get famous or to get rich.”

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/27/percival-everetts-deadly-serious-comedy

Books

September 27, 2021 Issue

Percival Everett’s Deadly Serious Comedy

The novelist has regularly exploded our models of genre and identity. In “The Trees,” he’s raising the stakes, confronting America’s legacy of lynching in a mystery at once hilarious and horrifying.

by Julian Lucas

September 20, 2021

The New Yorker

IMAGE: In “The Trees,” a postmodern thriller about lynchings avenged, a character remarks, “Dead is the new Black.” Illustration by Leonardo Santamaria

Percival Everett has one of the best poker faces in contemporary American literature. The author of twenty-two novels, he excels at the unblinking execution of extraordinary conceits. “If I can make you believe it, then it’s fair game,” he once said of his books, which range from elliptical thriller to genre-shattering farce; their narrators include a vengeful romance novelist (“The Water Cure”), a hyperliterate baby (“Glyph”), and a suicidal English professor risen from the dead (“American Desert”). Everett, sixty-four, is so consistently surprising that his agent once begged him to try repeating himself—advice he’s studiously ignored. “I’ve been called a Southern writer, a Western writer, an experimental writer, a mystery writer, and I find it all kind of silly,” he said earlier this year. “I write fiction.”

Beneath his work’s ever-changing surface lies an obsession with the instability of meaning, and with unpredictable shifts of identity. In his short story “The Appropriation of Cultures,” from 1996, a Black guitarist playing at a joint near the University of South Carolina is asked by a group of white fraternity brothers to sing “Dixie.” He obliges with a rendition so genuine that the secessionist anthem becomes his own, shaming the pranksters and eliciting an ovation. Later, he buys a used truck with a Confederate-flag decal, sparking a trend that turns the hateful symbol into an emblem of Black pride. The story ends with the flag’s removal from the state capitol: “There was no ceremony, no notice. One day, it was not there. Look away, look away, look away . . .”

Such commitment to the bit is exemplary of Everett’s fiction. Yet nothing he has written could be sufficient preparation for his latest book, “The Trees” (Graywolf), a murder mystery set in the town of Money, Mississippi. The novel begins, stealthily enough, as a mordant hillbilly comedy, Flannery O’Connor transposed to the age of QAnon. We are introduced to Wheat Bryant, an ex-trucker who lost his job in a viral drunk-driving incident; his faithless wife, Charlene; his cousin Junior Junior Milam; and his mother, Granny C, who zones out on a motorized shopping cart while the family bickers about hogs. The old woman appears to be having a stroke but is actually reflecting on “something I wished I hadn’t done. About the lie I told all them years back on that nigger boy”:

“Oh Lawd,” Charlene said. “We on that again.”

“I wronged that little pickaninny. Like it say in the good book, what goes around comes around.”

“What good book is that?” Charlene asked. “Guns and Ammo?”

Granny C, it turns out, is a fictionalized Carolyn Bryant Donham, whose accusation that Emmett Till had whistled at and grabbed her, at the country store in Money where she worked, instigated the twentieth century’s most notorious lynching. On August 28, 1955, Donham’s husband, Roy Bryant, and her brother-in-law J. W. Milam kidnapped, tortured, and killed the fourteen-year-old boy for violating the color line. The case drew condemnation throughout the world but ended in Bryant and Milam’s acquittal by an all-white jury. (They later confessed to a reporter in exchange for three thousand dollars.) Donham, alleged by some witnesses to have participated in the abduction, went on to live in peaceful anonymity—until 2017, when, in an interview with the historian Timothy Tyson, she admitted to fabricating details of her encounter with Till. The octogenarian “felt tender sorrow” over Till’s fate but offered no apology. Her longevity renewed outrage about the half-century-old crime: Till died at fourteen; his accuser lived to finish her memoirs, which are due to be made public in 2036.

“The Trees” is not much interested in anyone’s tender sorrow. In the opening chapters, Wheat and Junior Junior—invented sons of Till’s killers—are found castrated, and with barbed wire around their necks. Beside each white victim lies a dead Black man in a suit, disfigured as Till was and clutching the white man’s severed testicles like a trophy. Later, Granny C is found dead of shock beside an identical besuited corpse. Similar murders occur elsewhere in the area, and, each time, a spectral body appears, stirring terrified rumors of a “walking dead Negro man.” The killings spread throughout the country; in several Western states, the vanishing corpse seems to be that of an Asian man. Is it the handiwork of a serial killer? A cadre of vigilante assassins? A swarm of vengeful ghosts?

Into this maelstrom Everett hurls three Black detectives: Ed Morgan, a gentle giant with a young family; Jim Davis, a wisecracking bachelor; and Herberta Hind, a misanthropic professional who joined the F.B.I. to spite her radical parents. (Jim and Ed work for the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, often to their embarrassment: “That’s some crazy shit to yell out. MBI! Fucking ridiculous.”) Received with fear and prejudice by the town’s white citizens, the trio feels distinctly ambivalent about the case, which they initially treat as a dark joke. “Maybe it’s some kind of Black ninja,” Jim says. “Jamal Lee swinging lengths of barbed wire in Money, Mississippi.”

The detectives zero in on what seems like a conspiracy involving a soul-food restaurant (with a secret dojo) and a centenarian root doctor, Mama Z, who keeps records of every lynching in America. The stage is set for a Black-cop ex machina à la “In the Heat of the Night,” “BlacKkKlansman,” or the 2021 New York mayoral election. But the detectives quickly find themselves in the wrong genre of justice. What begins as a macabre sendup of the unreconstructed South culminates in a more unsettling and possibly supernatural wave of vengeance, as the killings assume the dimensions of an Old Testament plague:

Some called it a throng. A reporter on the scene used the word horde. A minister of an AME church in Jefferson County, Mississippi, called it a congregation . . . and like a tornado it would destroy one life and leave the one beside it unscathed. It made a noise. A moan that filled the air. Rise, it said, Rise. It left towns torn apart. Families grieved. Families assessed their histories. It was weather. Rise. It was a cloud. It was a front, a front of dead air.

The unresolved legacy of lynching might seem like a surprising choice of theme for the cool, analytic, and resolutely idiosyncratic Percival Everett. Brought up in a family of doctors and dentists, in Columbia, South Carolina, he studied the philosophy of language in graduate school, drifting from the dissection of invented dialogue into full-blown fiction organically. He wrote his début novel, “Suder” (1983)—the story of a baseball player’s madcap odyssey after a humiliating slump—as a master’s student in creative writing at Brown, where he met the great literary trickster Robert Coover. Everett, too, established himself as an author of terse and wily postmodern fiction, drawing on such influences as Lewis Carroll, Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, and, especially, Laurence Sterne, whose “Tristram Shandy” remains a model for his playfully withholding work.

A character named Percival Everett makes opaque cameos in several of his novels but offers few keys to his creator’s life. Publicity-avoidant—he told audiences on his one book tour, for his twelfth novel, “Erasure” (2001), that he was there only because he needed money for a new roof—Everett likes to downplay his literary vocation. He routinely describes fiction as a sideline to hands-on pursuits like fly-fishing, wood carving, ranching, and training animals, especially horses, whom he credits with teaching him to write. Everett himself teaches English at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife, Danzy Senna, a novelist and a fellow U.S.C. faculty member. Yet he’s reluctant to admit that he has anything to teach. He speaks of writing fiction as a Zen-like process of unlearning, each novel leaving him more aware of his ignorance than the last. As he once said, “My goal is to know nothing, and my friends tell me I’m well on my way.”

His protagonists, too, are buffeted by destabilizing revelations—crises of identity that double as crises of genre. In “American Desert” (2004), the jolt of being resurrected forces Ted Street to reëvaluate a broken marriage, even as Christian fundamentalists try to conscript him into millenarian schemes. Baby Ralph, the narrator of “Glyph” (2014), terrifies adults with his mastery of language—especially his father, an insecure post-structuralist academic—upending several disciplines by writing prodigiously yet refusing to speak. (“I was a baby fat with words, but I made no sound,” he reflects.) The novel is a characteristically Everett mixture of deadpan wit, slapstick accident, and serious philosophical inquiry, often conducted by famous figures cribbed from reality: Hurston, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and an inexplicably heterosexual Roland Barthes.

An Oprah Winfrey stand-in makes an appearance in “Erasure,” Everett’s best-known work, which ridicules the pressure on Black writers to publish “authentic” testimonials of urban poverty. Thelonious Ellison, a frustrated author of rarefied experimental fiction, is caring for his Alzheimer’s-stricken mother when he learns about “We’s Lives in Da Ghetto,” a runaway best-seller by a Black Oberlin graduate. Ellison is so enraged that he writes a pseudonymous parody, titled “My Pafology” (later simply “Fuck”), which is included as a novel within the novel. To his astonishment, it becomes a best-seller—an irony compounded by the breakout success of “Erasure.”

Another cat-and-mouse game with stereotypes unfolds in Everett’s hilarious “I Am Not Sidney Poitier” (2009), a picaresque story of a wealthy Black orphan with a fatefully strange name. Not Sidney Poitier, as he is called, is raised by servants on the estate of Ted Turner, the founder of CNN, because his late mother made a generous investment in a predecessor of the network. Unencumbered by family, necessity, or identity, he sets off on a series of adventures that riff on his eponym’s films. The actor’s cipher-like versatility—a dignified emissary of Black America in every role—provides endless material for parody: Not Sidney escapes from prison shackled to another inmate (“The Defiant Ones”), dates a light-skinned girl from a colorist family (“Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner”), and fixes a roof for a commune of religious women (“Lilies of the Field”). Yet a darker theme of self-surrender runs throughout. During an extended allusion to “In the Heat of the Night,” Not Sidney is asked to examine what appears to be his own dead body at an Alabama police station:

As we stepped out of the makeshift morgue, I thought that if that body in the chest was Not Sidney Poitier, then I was not Not Sidney Poitier and that by all I knew of double negatives, I was therefore Sidney Poitier.

Corpses are omnipresent in Everett’s fiction, their disruptive energies catalyzing important revelations. In his comic novels, they often fall prey to cultists, body snatchers, and creepy morticians, serving as carnivalesque reminders of the self’s plasticity. In his thrillers, mostly set in the American West, they become traces of atrocities that might otherwise remain invisible: torture, toxic pollution, massacres, femicide. Novels such as“Watershed” (1996), “Wounded” (2005), “The Water Cure” (2007), and “Assumption” (2011) feature loners whose rugged isolation—usually involving a lot of fly-fishing—is interrupted by encounters with the dead, who lure them into deeper currents of violence.

The deaths of children loom large, especially in Everett’s previous two novels, both of which make the shock of mortality the basis of formal experiments. “So Much Blue” (2017), a painter’s story, unfolds in three parallel time lines centered on nested secrets: an extramarital affair, an immense blue masterpiece locked in a barn, and the traumatic memory of a little girl’s death in war-torn El Salvador. “Telephone” (2020), which was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize, is split even more dramatically. The story of a middle-aged geologist’s struggle with his teen-age daughter’s terminal genetic disorder, it was issued in three nearly indistinguishable editions with separate endings. The novel’s epigraph, from Søren Kierkegaard, suggests the world’s bleakest choose-your-own-adventure: “Do it or do not do it—you will regret both.” But the geologist’s inevitable loss is also strangely freeing; with nothing left to fear, he attempts a mad act of heroism in the rural Southwest, drawn by an anonymous note that reads “Please Help Us.”

Death issues a more terrifying summons in Everett’s gripping “The Body of Martin Aguilera” (1997), a compact work set in the canyons of northern New Mexico. A retired professor discovers his neighbor dead at home. Soon after he reports the apparent killing, the body vanishes—only to reappear, seemingly drowned, in a nearby river. The professor suspects foul play, and his investigation reveals a vast ecological crime. Everything depends on his ability to overcome fear and repulsion as he fights to secure the body. In a pivotal scene, he attends a clandestine funeral where members of a lay Catholic brotherhood, the Penitentes, scourge themselves as they process around a putrefying dead man. In a violent culture afraid of mortality, the willingness to be intimate with death can be a form of vigilance.

“The Trees,” Everett’s longest book yet, synthesizes many of these abiding preoccupations: race and media, symbols and appropriation, and, especially, the unsettling power of corpses to shock and reorient the living. The novel can be read as a grisly fable about whose murder counts in the public imagination—reprising the question that Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, confronted in 1955: How do you make America notice Black death?

The lynched body originally functioned as a weapon of white-supremacist terror. Strung up from trees or bridges and photographed for macabre postcards, victims were transformed into banners for the cause that had taken their lives. But in 1955 Till-Mobley made the historic decision to hold an open-casket viewing of her maimed son, galvanizing millions against segregation and lynching. She reappropriated her son’s death from his killers, who had intended it as an act of intimidation, and turned it into an act of defiance, inviting press photographers and crowds of strangers to, in her words, “let the world see what I’ve seen.”

Less well known than the funeral is Till-Mobley’s struggle to recover her son’s body. Mississippi authorities were rushing to bury it when news of his death reached her, in Chicago. After they finally agreed to surrender the body, they sent it in a sealed casket, with instructions that it never be opened. Later, Till-Mobley had to fight for her son’s body in court, where his killers’ attorneys argued that it was too decomposed for reliable identification. Till was probably still alive, they suggested, conspiratorially speculating that the N.A.A.C.P. had staged the lynching.

In “The Trees,” this bad-faith defense returns with vengeful irony, as staged Black cadavers appear at the scene of each murder in Money. What in 1955 was a calculated blindness about lynching becomes not a proof of power but a sign of weakness: the body that Mississippi once refused to recognize comes back as a terror its citizens cannot understand. Everett envisages the town as stalked by sinister allusions, shadows of the pervasive past. Billboards encourage visitors to “pull a catfish out of the Little Tallahatchie! They’s good eating!” (It was a boy checking catfish nets in the river who discovered Till’s body.) When Charlene Bryant is asked if she can identify the man at the scene of her husband’s murder, she replies, “His own Black mama couldn’t have knowed him.”

The slip is characteristic of a novel that uses humor less to provoke laughter than to eviscerate false innocence—funny, yes, but mostly in the maddening way that it was funny when the cops who arrested Dylann Roof treated him to Burger King. Everett’s scathing portrayal of Money’s self-protective amnesia has an affinity with the artist Kerry James Marshall’s “Heirlooms and Accessories,” a triptych of prints depicting lockets that contain black-and-white photographs of different smiling white women. Though each may be someone’s beloved grandmother, the portraits are excerpted from a 1930 photograph of a lynching; every individual is an “accessory” to murder. The killings in “The Trees” represent an even more striking attempt to return focus to the culprits. One suspect in the murders explains, “If that Griffin book had been Lynched Like Me, America might have looked up from dinner or baseball.”

There’s a certain self-referential exhaustion to the novel’s killings, which can be understood as a kind of despairing joke: for the country to really care about dead Black people, they’d have to be found next to white ones. And even if the repressed violence of American history did erupt, few would recognize it for what it was. Everett’s townspeople concoct copious theories about the killings—mass delusion, a race war, satanic assassins capable of faking death—but hardly anyone draws the connection to Emmett Till. When the killings reach the White House, a Trump-like President cowers under the Resolute desk and wonders if Ben Carson might be to blame.

The satire’s ultimate target is America’s inability to make cultural sense of atrocities that it has never fully acknowledged, much less atoned for. Its persistent flights from the obvious evoke the evasions of our era, as the unprecedented visibility of racist killings gives rise to new strains of misdirection, exploitation, and apathy. In one memorable scene, Jim tracks the vanishing corpses to a warehouse in Chicago, the aptly named Acme Cadaver Company. The bathetic tableau recalls the video for Childish Gambino’s “This Is America,” a vision of mass entertainment laundering mass death:

It was like a cleaner’s facility, except instead of shirts, blouses, and jackets, corpses, women and men, slid by on suspended rails. Farther away, through the center of the room, naked cadavers glided along, head to toe, on a conveyer belt. The music of the Jackson Five blared. A-B-C. One two three. Chicago Bears and Bulls banners hung from the ceiling some twenty feet above them. . . . The music changed to Marvin Gaye. What was going on?

“The Trees” is an almost disconcertingly smooth narrative, the short chapters dealt as quickly as cards. Gruesome scenes and hardboiled detective banter alternate with comic vignettes (F.B.I. antics, an online white-supremacist meeting) and stark meditations on what one character describes as the slow “genocide” of American lynching. The mystery itself is tightly constructed and suspensefully paced—until, as in Everett’s other novels, a chasm opens between form and content. The tension, in this case, lies between the open-and-shut conventions of the crime novel and the immensity of Everett’s subject.

Nobody feels this more keenly than the trio of detectives, who are constantly stymied by being “Black and blue.” The white residents of Money hate them out of prejudice; the Black ones distrust them as cops. “You’re from the F.B.I.,” Mama Z tells Herberta when questioned about her archives. Herberta says, “I’m also a Black woman.” Mama Z replies, “So you see my problem.” The discomfort between the two mirrors the divisions of last summer’s uprising, when many protesters found themselves on the other side of cordons and curfews enforced by Black officers and mayors. In one uncanny moment, the detectives arrive at a bar in Money’s Black neighborhood just as a young woman with a Mohawk begins a haunting performance of “Strange Fruit.” The scene quietly undercuts any presumption of racial solidarity, as the watching officers realize that they’ve been shut out of a community secret.

Everett’s novel seems to look askance even at itself. When Damon Thruff, a young Black professor specializing in the history of lynching, arrives in Money to assist Mama Z, she tells him that she’s read his work and finds it unfeeling: “You were able to construct three hundred and seven pages on such a topic without an ounce of outrage.” The figure is curiously close to the number of pages in “The Trees,” implicitly questioning not only Damon’s sang-froid but Everett’s. Novels about the legacy of racist violence often strive to voice buried emotion. Bernice L. McFadden’s “Gathering of Waters” (2012), another novel about Emmett Till, is elegiacally narrated by the collective consciousness of Money. Jesmyn Ward’s “Sing, Unburied, Sing” (2017), also set in Mississippi, grieves for victims of the state’s Parchman Farm penitentiary through the lyrical narration of ghosts.

“The Trees,” by contrast, is as cold and matter-of-fact as Mama Z’s lynching archive, where the drawers are “like those in a morgue.” Uncharacteristically for Everett, who is known for cerebral narrators, the novel surveys a wide cast from an indifferent third-person remove. Sometimes Everett appears reluctant to commit his attention, or to decide between drawing caricatures and fleshing out human quandaries. Is this the story of Granny C’s agonized comeuppance? Mama Z’s patient revenge? The alienation of Jim, Ed, and Herberta, as they pursue vigilantes with whom they quietly sympathize? No character is allowed quite enough presence to say. But denying readers a surrogate is also a strategy, turning the moral crisis back onto us, unresolved.

To make art about lynching is an increasingly fraught endeavor. Since Mamie Till-Mobley’s decision to “let the world see,” the pendulum has swung back to a suspicion that many representations of anti-Black violence risk offering up their subjects to a mob’s eyes. When the artist Dana Schutz, who is white, exhibited her painting of Emmett Till’s mangled face in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, protesters demanded its removal and encouraged her to destroy it. At the time, the debate was largely about who should be entitled to such an image, and whether that line ought to be drawn on the basis of race. Schutz’s defenders frequently pointed out that Henry Taylor, a Black artist, had a painting of Philando Castile’s killing in the same show.

Now, though, scrutiny has fallen on such representations regardless of who creates them. The bereaved relatives of police-killing victims have begun to challenge Black artists and activists for adapting, and even profiting from, images of their dead loved ones. Many writers, especially of the Afropessimist school, argue that Black trauma has been hijacked by narratives of redemption, as names like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor cease to refer to individuals and become—by a kind of necromancy—avatars of others’ political ideals. “Dead is the new Black,” as one of Everett’s suspects quips.

“The Trees,” in its rigorous denial of sentiment, shuts down such catharsis—as if to say that funeral oratory is inappropriate when so many victims have yet to be counted. As Damon, the scholar, begins working in Mama Z’s archives, he is most disturbed by lynching’s effacement of individuality:

The crime, the practice, the religion of it, was becoming more pernicious as he realized that the similarity of their deaths had caused these men and women to be at once erased and coalesced like one piece, like one body. They were all number and no number at all, many and one, a symptom, a sign.

Suddenly, he feels compelled to write down each victim’s name in pencil and erase it. From Emmett Till to Alton Sterling, the list occupies an entire chapter.

The focus shifts from Everett’s characters to the phenomenon of lynching in all its geographic breadth, intangible influence, and individual particularity. Beyond the South, there are revenge killings in Rock Springs, Wyoming, where dozens of Chinese miners were massacred, in 1885; in Carbon County, Utah, where a Black coal miner was hanged from a cottonwood tree, in 1925; and in Duluth, Minnesota, where an unemployed man fondly reflects on his grandfather’s role in the town’s lynching of three Black men, in 1920. (He wishes someone would do the same to the “fucking Hispanics” who took his job.) The novel makes good on its title’s promise, as the trees of a particular mystery recede into the forest of an ongoing crime. ♦

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Julian Lucas is a staff writer at The New Yorker. His writing for the magazine includes an exploration of slavery reënactments, as well as profiles of artists and writers such as El Anatsui and Ishmael Reed. Previously, he was an associate editor at Cabinet and a contributing editor at The Point. His writing has appeared in The New York Review of Books, Vanity Fair, Harper’s Magazine, Art in America, and the New York Times Book Review, where he was a contributing writer.

http://bombmagazine.org/article/2666/percival-everett

Percival Everett has one of the best poker faces in contemporary American literature. The author of twenty-two novels, he excels at the unblinking execution of extraordinary conceits. “If I can make you believe it, then it’s fair game,” he once said of his books, which range from elliptical thriller to genre-shattering farce; their narrators include a vengeful romance novelist (“The Water Cure”), a hyperliterate baby (“Glyph”), and a suicidal English professor risen from the dead (“American Desert”). Everett, sixty-four, is so consistently surprising that his agent once begged him to try repeating himself—advice he’s studiously ignored. “I’ve been called a Southern writer, a Western writer, an experimental writer, a mystery writer, and I find it all kind of silly,” he said earlier this year. “I write fiction.”

Beneath his work’s ever-changing surface lies an obsession with the instability of meaning, and with unpredictable shifts of identity. In his short story “The Appropriation of Cultures,” from 1996, a Black guitarist playing at a joint near the University of South Carolina is asked by a group of white fraternity brothers to sing “Dixie.” He obliges with a rendition so genuine that the secessionist anthem becomes his own, shaming the pranksters and eliciting an ovation. Later, he buys a used truck with a Confederate-flag decal, sparking a trend that turns the hateful symbol into an emblem of Black pride. The story ends with the flag’s removal from the state capitol: “There was no ceremony, no notice. One day, it was not there. Look away, look away, look away . . .”

Such commitment to the bit is exemplary of Everett’s fiction. Yet nothing he has written could be sufficient preparation for his latest book, “The Trees” (Graywolf), a murder mystery set in the town of Money, Mississippi. The novel begins, stealthily enough, as a mordant hillbilly comedy, Flannery O’Connor transposed to the age of QAnon. We are introduced to Wheat Bryant, an ex-trucker who lost his job in a viral drunk-driving incident; his faithless wife, Charlene; his cousin Junior Junior Milam; and his mother, Granny C, who zones out on a motorized shopping cart while the family bickers about hogs. The old woman appears to be having a stroke but is actually reflecting on “something I wished I hadn’t done. About the lie I told all them years back on that nigger boy”:

“Oh Lawd,” Charlene said. “We on that again.”

“I wronged that little pickaninny. Like it say in the good book, what goes around comes around.”

“What good book is that?” Charlene asked. “Guns and Ammo?”

Granny C, it turns out, is a fictionalized Carolyn Bryant Donham, whose accusation that Emmett Till had whistled at and grabbed her, at the country store in Money where she worked, instigated the twentieth century’s most notorious lynching. On August 28, 1955, Donham’s husband, Roy Bryant, and her brother-in-law J. W. Milam kidnapped, tortured, and killed the fourteen-year-old boy for violating the color line. The case drew condemnation throughout the world but ended in Bryant and Milam’s acquittal by an all-white jury. (They later confessed to a reporter in exchange for three thousand dollars.) Donham, alleged by some witnesses to have participated in the abduction, went on to live in peaceful anonymity—until 2017, when, in an interview with the historian Timothy Tyson, she admitted to fabricating details of her encounter with Till. The octogenarian “felt tender sorrow” over Till’s fate but offered no apology. Her longevity renewed outrage about the half-century-old crime: Till died at fourteen; his accuser lived to finish her memoirs, which are due to be made public in 2036.

“The Trees” is not much interested in anyone’s tender sorrow. In the opening chapters, Wheat and Junior Junior—invented sons of Till’s killers—are found castrated, and with barbed wire around their necks. Beside each white victim lies a dead Black man in a suit, disfigured as Till was and clutching the white man’s severed testicles like a trophy. Later, Granny C is found dead of shock beside an identical besuited corpse. Similar murders occur elsewhere in the area, and, each time, a spectral body appears, stirring terrified rumors of a “walking dead Negro man.” The killings spread throughout the country; in several Western states, the vanishing corpse seems to be that of an Asian man. Is it the handiwork of a serial killer? A cadre of vigilante assassins? A swarm of vengeful ghosts?

Into this maelstrom Everett hurls three Black detectives: Ed Morgan, a gentle giant with a young family; Jim Davis, a wisecracking bachelor; and Herberta Hind, a misanthropic professional who joined the F.B.I. to spite her radical parents. (Jim and Ed work for the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, often to their embarrassment: “That’s some crazy shit to yell out. MBI! Fucking ridiculous.”) Received with fear and prejudice by the town’s white citizens, the trio feels distinctly ambivalent about the case, which they initially treat as a dark joke. “Maybe it’s some kind of Black ninja,” Jim says. “Jamal Lee swinging lengths of barbed wire in Money, Mississippi.”

The detectives zero in on what seems like a conspiracy involving a soul-food restaurant (with a secret dojo) and a centenarian root doctor, Mama Z, who keeps records of every lynching in America. The stage is set for a Black-cop ex machina à la “In the Heat of the Night,” “BlacKkKlansman,” or the 2021 New York mayoral election. But the detectives quickly find themselves in the wrong genre of justice. What begins as a macabre sendup of the unreconstructed South culminates in a more unsettling and possibly supernatural wave of vengeance, as the killings assume the dimensions of an Old Testament plague:

Some called it a throng. A reporter on the scene used the word horde. A minister of an AME church in Jefferson County, Mississippi, called it a congregation . . . and like a tornado it would destroy one life and leave the one beside it unscathed. It made a noise. A moan that filled the air. Rise, it said, Rise. It left towns torn apart. Families grieved. Families assessed their histories. It was weather. Rise. It was a cloud. It was a front, a front of dead air.

The unresolved legacy of lynching might seem like a surprising choice of theme for the cool, analytic, and resolutely idiosyncratic Percival Everett. Brought up in a family of doctors and dentists, in Columbia, South Carolina, he studied the philosophy of language in graduate school, drifting from the dissection of invented dialogue into full-blown fiction organically. He wrote his début novel, “Suder” (1983)—the story of a baseball player’s madcap odyssey after a humiliating slump—as a master’s student in creative writing at Brown, where he met the great literary trickster Robert Coover. Everett, too, established himself as an author of terse and wily postmodern fiction, drawing on such influences as Lewis Carroll, Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, and, especially, Laurence Sterne, whose “Tristram Shandy” remains a model for his playfully withholding work.

A character named Percival Everett makes opaque cameos in several of his novels but offers few keys to his creator’s life. Publicity-avoidant—he told audiences on his one book tour, for his twelfth novel, “Erasure” (2001), that he was there only because he needed money for a new roof—Everett likes to downplay his literary vocation. He routinely describes fiction as a sideline to hands-on pursuits like fly-fishing, wood carving, ranching, and training animals, especially horses, whom he credits with teaching him to write. Everett himself teaches English at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife, Danzy Senna, a novelist and a fellow U.S.C. faculty member. Yet he’s reluctant to admit that he has anything to teach. He speaks of writing fiction as a Zen-like process of unlearning, each novel leaving him more aware of his ignorance than the last. As he once said, “My goal is to know nothing, and my friends tell me I’m well on my way.”

His protagonists, too, are buffeted by destabilizing revelations—crises of identity that double as crises of genre. In “American Desert” (2004), the jolt of being resurrected forces Ted Street to reëvaluate a broken marriage, even as Christian fundamentalists try to conscript him into millenarian schemes. Baby Ralph, the narrator of “Glyph” (2014), terrifies adults with his mastery of language—especially his father, an insecure post-structuralist academic—upending several disciplines by writing prodigiously yet refusing to speak. (“I was a baby fat with words, but I made no sound,” he reflects.) The novel is a characteristically Everett mixture of deadpan wit, slapstick accident, and serious philosophical inquiry, often conducted by famous figures cribbed from reality: Hurston, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and an inexplicably heterosexual Roland Barthes.

An Oprah Winfrey stand-in makes an appearance in “Erasure,” Everett’s best-known work, which ridicules the pressure on Black writers to publish “authentic” testimonials of urban poverty. Thelonious Ellison, a frustrated author of rarefied experimental fiction, is caring for his Alzheimer’s-stricken mother when he learns about “We’s Lives in Da Ghetto,” a runaway best-seller by a Black Oberlin graduate. Ellison is so enraged that he writes a pseudonymous parody, titled “My Pafology” (later simply “Fuck”), which is included as a novel within the novel. To his astonishment, it becomes a best-seller—an irony compounded by the breakout success of “Erasure.”

Another cat-and-mouse game with stereotypes unfolds in Everett’s hilarious “I Am Not Sidney Poitier” (2009), a picaresque story of a wealthy Black orphan with a fatefully strange name. Not Sidney Poitier, as he is called, is raised by servants on the estate of Ted Turner, the founder of CNN, because his late mother made a generous investment in a predecessor of the network. Unencumbered by family, necessity, or identity, he sets off on a series of adventures that riff on his eponym’s films. The actor’s cipher-like versatility—a dignified emissary of Black America in every role—provides endless material for parody: Not Sidney escapes from prison shackled to another inmate (“The Defiant Ones”), dates a light-skinned girl from a colorist family (“Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner”), and fixes a roof for a commune of religious women (“Lilies of the Field”). Yet a darker theme of self-surrender runs throughout. During an extended allusion to “In the Heat of the Night,” Not Sidney is asked to examine what appears to be his own dead body at an Alabama police station:

As we stepped out of the makeshift morgue, I thought that if that body in the chest was Not Sidney Poitier, then I was not Not Sidney Poitier and that by all I knew of double negatives, I was therefore Sidney Poitier.

Corpses are omnipresent in Everett’s fiction, their disruptive energies catalyzing important revelations. In his comic novels, they often fall prey to cultists, body snatchers, and creepy morticians, serving as carnivalesque reminders of the self’s plasticity. In his thrillers, mostly set in the American West, they become traces of atrocities that might otherwise remain invisible: torture, toxic pollution, massacres, femicide. Novels such as“Watershed” (1996), “Wounded” (2005), “The Water Cure” (2007), and “Assumption” (2011) feature loners whose rugged isolation—usually involving a lot of fly-fishing—is interrupted by encounters with the dead, who lure them into deeper currents of violence.

The deaths of children loom large, especially in Everett’s previous two novels, both of which make the shock of mortality the basis of formal experiments. “So Much Blue” (2017), a painter’s story, unfolds in three parallel time lines centered on nested secrets: an extramarital affair, an immense blue masterpiece locked in a barn, and the traumatic memory of a little girl’s death in war-torn El Salvador. “Telephone” (2020), which was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize, is split even more dramatically. The story of a middle-aged geologist’s struggle with his teen-age daughter’s terminal genetic disorder, it was issued in three nearly indistinguishable editions with separate endings. The novel’s epigraph, from Søren Kierkegaard, suggests the world’s bleakest choose-your-own-adventure: “Do it or do not do it—you will regret both.” But the geologist’s inevitable loss is also strangely freeing; with nothing left to fear, he attempts a mad act of heroism in the rural Southwest, drawn by an anonymous note that reads “Please Help Us.”

Death issues a more terrifying summons in Everett’s gripping “The Body of Martin Aguilera” (1997), a compact work set in the canyons of northern New Mexico. A retired professor discovers his neighbor dead at home. Soon after he reports the apparent killing, the body vanishes—only to reappear, seemingly drowned, in a nearby river. The professor suspects foul play, and his investigation reveals a vast ecological crime. Everything depends on his ability to overcome fear and repulsion as he fights to secure the body. In a pivotal scene, he attends a clandestine funeral where members of a lay Catholic brotherhood, the Penitentes, scourge themselves as they process around a putrefying dead man. In a violent culture afraid of mortality, the willingness to be intimate with death can be a form of vigilance.

“The Trees,” Everett’s longest book yet, synthesizes many of these abiding preoccupations: race and media, symbols and appropriation, and, especially, the unsettling power of corpses to shock and reorient the living. The novel can be read as a grisly fable about whose murder counts in the public imagination—reprising the question that Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, confronted in 1955: How do you make America notice Black death?

The lynched body originally functioned as a weapon of white-supremacist terror. Strung up from trees or bridges and photographed for macabre postcards, victims were transformed into banners for the cause that had taken their lives. But in 1955 Till-Mobley made the historic decision to hold an open-casket viewing of her maimed son, galvanizing millions against segregation and lynching. She reappropriated her son’s death from his killers, who had intended it as an act of intimidation, and turned it into an act of defiance, inviting press photographers and crowds of strangers to, in her words, “let the world see what I’ve seen.”

Less well known than the funeral is Till-Mobley’s struggle to recover her son’s body. Mississippi authorities were rushing to bury it when news of his death reached her, in Chicago. After they finally agreed to surrender the body, they sent it in a sealed casket, with instructions that it never be opened. Later, Till-Mobley had to fight for her son’s body in court, where his killers’ attorneys argued that it was too decomposed for reliable identification. Till was probably still alive, they suggested, conspiratorially speculating that the N.A.A.C.P. had staged the lynching.

In “The Trees,” this bad-faith defense returns with vengeful irony, as staged Black cadavers appear at the scene of each murder in Money. What in 1955 was a calculated blindness about lynching becomes not a proof of power but a sign of weakness: the body that Mississippi once refused to recognize comes back as a terror its citizens cannot understand. Everett envisages the town as stalked by sinister allusions, shadows of the pervasive past. Billboards encourage visitors to “pull a catfish out of the Little Tallahatchie! They’s good eating!” (It was a boy checking catfish nets in the river who discovered Till’s body.) When Charlene Bryant is asked if she can identify the man at the scene of her husband’s murder, she replies, “His own Black mama couldn’t have knowed him.”

The slip is characteristic of a novel that uses humor less to provoke laughter than to eviscerate false innocence—funny, yes, but mostly in the maddening way that it was funny when the cops who arrested Dylann Roof treated him to Burger King. Everett’s scathing portrayal of Money’s self-protective amnesia has an affinity with the artist Kerry James Marshall’s “Heirlooms and Accessories,” a triptych of prints depicting lockets that contain black-and-white photographs of different smiling white women. Though each may be someone’s beloved grandmother, the portraits are excerpted from a 1930 photograph of a lynching; every individual is an “accessory” to murder. The killings in “The Trees” represent an even more striking attempt to return focus to the culprits. One suspect in the murders explains, “If that Griffin book had been Lynched Like Me, America might have looked up from dinner or baseball.”

There’s a certain self-referential exhaustion to the novel’s killings, which can be understood as a kind of despairing joke: for the country to really care about dead Black people, they’d have to be found next to white ones. And even if the repressed violence of American history did erupt, few would recognize it for what it was. Everett’s townspeople concoct copious theories about the killings—mass delusion, a race war, satanic assassins capable of faking death—but hardly anyone draws the connection to Emmett Till. When the killings reach the White House, a Trump-like President cowers under the Resolute desk and wonders if Ben Carson might be to blame.

The satire’s ultimate target is America’s inability to make cultural sense of atrocities that it has never fully acknowledged, much less atoned for. Its persistent flights from the obvious evoke the evasions of our era, as the unprecedented visibility of racist killings gives rise to new strains of misdirection, exploitation, and apathy. In one memorable scene, Jim tracks the vanishing corpses to a warehouse in Chicago, the aptly named Acme Cadaver Company. The bathetic tableau recalls the video for Childish Gambino’s “This Is America,” a vision of mass entertainment laundering mass death:

It was like a cleaner’s facility, except instead of shirts, blouses, and jackets, corpses, women and men, slid by on suspended rails. Farther away, through the center of the room, naked cadavers glided along, head to toe, on a conveyer belt. The music of the Jackson Five blared. A-B-C. One two three. Chicago Bears and Bulls banners hung from the ceiling some twenty feet above them. . . . The music changed to Marvin Gaye. What was going on?

“The Trees” is an almost disconcertingly smooth narrative, the short chapters dealt as quickly as cards. Gruesome scenes and hardboiled detective banter alternate with comic vignettes (F.B.I. antics, an online white-supremacist meeting) and stark meditations on what one character describes as the slow “genocide” of American lynching. The mystery itself is tightly constructed and suspensefully paced—until, as in Everett’s other novels, a chasm opens between form and content. The tension, in this case, lies between the open-and-shut conventions of the crime novel and the immensity of Everett’s subject.

Nobody feels this more keenly than the trio of detectives, who are constantly stymied by being “Black and blue.” The white residents of Money hate them out of prejudice; the Black ones distrust them as cops. “You’re from the F.B.I.,” Mama Z tells Herberta when questioned about her archives. Herberta says, “I’m also a Black woman.” Mama Z replies, “So you see my problem.” The discomfort between the two mirrors the divisions of last summer’s uprising, when many protesters found themselves on the other side of cordons and curfews enforced by Black officers and mayors. In one uncanny moment, the detectives arrive at a bar in Money’s Black neighborhood just as a young woman with a Mohawk begins a haunting performance of “Strange Fruit.” The scene quietly undercuts any presumption of racial solidarity, as the watching officers realize that they’ve been shut out of a community secret.

Everett’s novel seems to look askance even at itself. When Damon Thruff, a young Black professor specializing in the history of lynching, arrives in Money to assist Mama Z, she tells him that she’s read his work and finds it unfeeling: “You were able to construct three hundred and seven pages on such a topic without an ounce of outrage.” The figure is curiously close to the number of pages in “The Trees,” implicitly questioning not only Damon’s sang-froid but Everett’s. Novels about the legacy of racist violence often strive to voice buried emotion. Bernice L. McFadden’s “Gathering of Waters” (2012), another novel about Emmett Till, is elegiacally narrated by the collective consciousness of Money. Jesmyn Ward’s “Sing, Unburied, Sing” (2017), also set in Mississippi, grieves for victims of the state’s Parchman Farm penitentiary through the lyrical narration of ghosts.

“The Trees,” by contrast, is as cold and matter-of-fact as Mama Z’s lynching archive, where the drawers are “like those in a morgue.” Uncharacteristically for Everett, who is known for cerebral narrators, the novel surveys a wide cast from an indifferent third-person remove. Sometimes Everett appears reluctant to commit his attention, or to decide between drawing caricatures and fleshing out human quandaries. Is this the story of Granny C’s agonized comeuppance? Mama Z’s patient revenge? The alienation of Jim, Ed, and Herberta, as they pursue vigilantes with whom they quietly sympathize? No character is allowed quite enough presence to say. But denying readers a surrogate is also a strategy, turning the moral crisis back onto us, unresolved.

To make art about lynching is an increasingly fraught endeavor. Since Mamie Till-Mobley’s decision to “let the world see,” the pendulum has swung back to a suspicion that many representations of anti-Black violence risk offering up their subjects to a mob’s eyes. When the artist Dana Schutz, who is white, exhibited her painting of Emmett Till’s mangled face in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, protesters demanded its removal and encouraged her to destroy it. At the time, the debate was largely about who should be entitled to such an image, and whether that line ought to be drawn on the basis of race. Schutz’s defenders frequently pointed out that Henry Taylor, a Black artist, had a painting of Philando Castile’s killing in the same show.

Now, though, scrutiny has fallen on such representations regardless of who creates them. The bereaved relatives of police-killing victims have begun to challenge Black artists and activists for adapting, and even profiting from, images of their dead loved ones. Many writers, especially of the Afropessimist school, argue that Black trauma has been hijacked by narratives of redemption, as names like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor cease to refer to individuals and become—by a kind of necromancy—avatars of others’ political ideals. “Dead is the new Black,” as one of Everett’s suspects quips.

“The Trees,” in its rigorous denial of sentiment, shuts down such catharsis—as if to say that funeral oratory is inappropriate when so many victims have yet to be counted. As Damon, the scholar, begins working in Mama Z’s archives, he is most disturbed by lynching’s effacement of individuality:

The crime, the practice, the religion of it, was becoming more pernicious as he realized that the similarity of their deaths had caused these men and women to be at once erased and coalesced like one piece, like one body. They were all number and no number at all, many and one, a symptom, a sign.

Suddenly, he feels compelled to write down each victim’s name in pencil and erase it. From Emmett Till to Alton Sterling, the list occupies an entire chapter.

The focus shifts from Everett’s characters to the phenomenon of lynching in all its geographic breadth, intangible influence, and individual particularity. Beyond the South, there are revenge killings in Rock Springs, Wyoming, where dozens of Chinese miners were massacred, in 1885; in Carbon County, Utah, where a Black coal miner was hanged from a cottonwood tree, in 1925; and in Duluth, Minnesota, where an unemployed man fondly reflects on his grandfather’s role in the town’s lynching of three Black men, in 1920. (He wishes someone would do the same to the “fucking Hispanics” who took his job.) The novel makes good on its title’s promise, as the trees of a particular mystery recede into the forest of an ongoing crime. ♦

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Julian Lucas is a staff writer at The New Yorker. His writing for the magazine includes an exploration of slavery reënactments, as well as profiles of artists and writers such as El Anatsui and Ishmael Reed. Previously, he was an associate editor at Cabinet and a contributing editor at The Point. His writing has appeared in The New York Review of Books, Vanity Fair, Harper’s Magazine, Art in America, and the New York Times Book Review, where he was a contributing writer.

http://bombmagazine.org/article/2666/percival-everett

Literature

All images courtesy of Percival Everett.

The novelist on what it means to be “absolutely human” and how American Idol is an “argument against democracy.”

I sat down to talk with novelist Percival Everett on the pretext of discussing his new epistolary novel, A History of the African American People [Proposed] by Strom Thurmond as Told to Percival Everett and James Kincaid , but truth be told, I was looking for any old reason. You see, Everett has three (that’s right, three) books slated for release this year: the aforementioned History (Akashic), a co-authored satire about the American obsession with celebrity and our political system—and yes, the two grow closer every day—as well as the sycophantic industry that is book publishing; the recently released American Desert (Hyperion), which concerns the misadventures of a college professor who is accidentally killed on his way to commit suicide, and the chaos that ensues after he sits up at his funeral, for all definitive purposes, alive; and a collection of stories, Damned If I Do (Graywolf), probably written just to complete the hat trick. In all, I desperately wanted to have a conversation with Percival that would be recorded for posterity, mainly because Percival Everett is a friggin’ genius. But don’t consider it odd if you’ve never heard of him, for although he’s by no means antisocial (on the contrary, he’s actually quite gregarious and generous with his time, teaching at the University of Southern California during the academic year and at various writing workshops during the summer), Everett actively shies away from the PR machinations and media attention that most other writers seek. And although he has published more than 15 works of well-received fiction (mostly with small presses, for reasons revealed in our conversation), his books are so stylistically varied that attempts to summarize his interests or creative oeuvre prove extremely difficult. In almost every one of his works you peel away one layer of references and meaning only to find another, only to then discover another, only to come upon another, until—well, you get the idea. Welcome, then, to an interview about everything, because in many ways the meaning of everything is the only subject Everett really writes about.

Rone Shavers Would you consider yourself an avant-garde or experimental writer?

Percival Everett I don’t know what avant-garde or experimental means. Every novel is experimental.

RS What do you think you’re bringing to the table in terms of American Arts and Letters? Do you see a purpose to your fiction?

PE Do you see a purpose to art? Of course there is a purpose to art, but do I see a function in my fiction? No. Is it going to feed anybody? No. Hopefully, the world is richer for more art being put into it. That’s what I care about.

RS Do you consider yourself a satirist? I say satire because of such works as A History of the African-American People [Proposed] by Strom Thurmond and Erasure, as well as Glyph. All three books poke fun at one aspect of American society or another. Is it important for you to have humor in your novels?

PE Humor is an interesting thing. It’s hard to do, but it allows you certain strategic advantages. If you can get someone laughing, then you can make them feel like shit a lot more easily. I’m not interested in sentimental stuff; I’m a little too self-conscious to pull it off.

RS I have this theory that Americans can only deal with serious work if it’s funny.

PE Aristophanes gets out a lot of great stuff because he’s funny, whereas you can only read Aeschylus in so many ways. His tragedies are beautiful but they’re limited. Likewise, if you read Kafka and don’t think it’s funny, you’re not reading Kafka very well. (laughter)

RS How do you categorize yourself as a writer? Do you work within the constraints of a particular fiction category? Your works are so all over the map.

PE No, whatever the particular work is, that’s what it is. I don’t put myself in a camp. I want to write what works for the story at hand. I serve the story, basically. I don’t think that as the author I’m terribly important, and I don’t want to be. I want to disappear. If anybody’s thinking about me when they’re reading my work I’ve failed as a writer. The work is supposed to stand by itself. I’m teaching you to fly. When you have to go solo, hey, I’m not there.

RS Does theory influence your work at all?

PE Only insofar as it’s a source. Anytime anybody goes through that much trouble to come up with something nonsensical you have to have fun with it. It’s hilarious stuff. It's not important that it means anything that takes us somewhere, because its not going to. But the fact that anybody wants to think it is, that’s fascinating.

RS Yet Glyph is influenced by semiotic theory and post-structuralism.

PE Well, I’m making fun of post-structuralism.

RS Even Erasure takes the piss out of theoretical positions, notably Gayatri Spivak’s idea of strategic essentialism. I am wondering if you yourself have a theoretical position that you’re working out.

PE If anybody thinks they’re actually going to delineate the necessary and sufficient conditions for any literary work of art, then they’re greatly mistaken and would probably be better served picking up some other line of work, like computer maintenance. But if you’re out to play with ideas and have some fun with them and admit that that’s what you’re doing, and don’t tell the regents at a university that . . . . It’s important to watch how ideas work and how they can be manipulated. That’s probably the most important question to me in the world. What can you do with thinking? But to take it seriously, I mean, that’s why the French, Derrida and Barthes, are so much fun. The fucking Americans get so earnest about this stuff that it stops being fun.

RS Well, what about the New Critics and their idea about the absolute autonomy of a work?

PE Oh, they need to take a pill. (laughter) Just chill.

RS But you do have that New Critical approach, especially if you say that the work is the work and that’s all there is.

PE Well I suppose, but I just don’t give a shit about the artist anyway. Why should I? If I find a painting a hundred years from now, and I can’t appreciate it until I find out something about the person who made it, it’s not much of a painting.

RS What would you describe as your aesthetic point of view? Do you have one?

PE What do I like? I like stuff that’s smart, stuff that challenges me and makes me think differently, that introduces me to things I didn’t know before.

RS Give me some examples.

PE Tristram Shandy is probably the best novel ever written. It takes every form of literary discourse of its time and exploits it. Huck Finn is fantastic. Chester Himes’s If He Hollers Let Him Go is a very sneaky book. And oddly anticipates so much of Invisible Man that it’s frightening.

RS I have a couple of questions about your style.

PE Style schmyle.

RS Your style, or lack thereof. (laughter) Do you have a predominant style?

PE Style is a tool. The work will dictate the style.

RS So you write in a manner that suits the work.

PE The only reason I would want a particular style is so that people could identify every work of mine as mine. There’s nothing at stake for me in having people recognize the work because of stylistic consistency.

RS You tend to blend styles a lot.

PE Well, I play with styles. I think they’re amusing. I think that anybody who thinks they have a style—it’s like watching punk rockers get ready to go out. It must take you two hours to get that look. How many safety pins do you need? To me there’s a wonderful irony in that. To work so hard to dress your work. Send the work out there naked.

RS What’s also interesting to me is the way you use history. Much of your work is dependent on historical events, but then the events tend to be jumbled; it’s not literal history, it’s mixed up. For instance, in Watershed, there is an infamous event from the American Indian Movement, but the novel is set in contemporary times.

PE I create a circumstance that’s similar to the siege at Wounded Knee. It’s interesting that you call it infamous. It’s a little like the American insistence on calling its attacks battles and the enemies’ attacks ambushes or massacres. History is like memories: it is constantly being reconstructed. History doesn’t exist without the lies. We believe in some way that history makes sense, but history is an amorphous, very strange creature that’s constantly changing.

RS Why do you rely on the historical so much?

PE Well, we live in a world. We define ourselves by the times through which we live. Everything is historical. If you read any philosophy now, you can’t help but be historical.

RS Why? I mean, I don’t read philosophy.

PE Can you understand any theory about the narrative of film if you don’t know Aristotle? The answer is no. Everything’s dependent on the work that’s come before it. Our understanding of philosophy is necessarily historical, because otherwise we wouldn’t be addressing anything. The problems of philosophy are historical: What is beautiful? What is a promise? How do we perceive?

RS Perception, and misperception, is a central issue in your work. Take Ralph, for example, the baby genius from Glyph. He’s so brilliant that he refuses to speak. The attempt to understand how people construct meaning leaves him flummoxed. And then there’s Thelonious, the writer in Erasure. He’s the victim of misperception after misperception, until he no longer recognizes himself. And then, of course, there’s Strom Thurmond, from the latest book. He actually becomes convinced he’s the best person capable of writing the history of black people in America.

PE Let me just say that I wish I could’ve made Thurmond up and that he didn’t exist. But sadly, he did exist. I’ve written a lot of books. Some of them are going to be that way, others are all based in contemporary story and don’t do that. I don’t think anyone living in any time cannot be interested in the past and its manipulation.

RS What if someone accused you of trying, in not necessarily a bad way, maybe a clever way, to rewrite African American history?

PE What the hell’s wrong with that? You can write anything you want to. If anybody takes anything they read, history or fiction, as some gospel, then fuck ’em anyway, who cares? The point is, take it and then play with it.

RS Would you say that your work is corrective?

PE I’m not correcting anything. That would mean I know enough to correct. I’m just a dumb writer.

RS Well then, what about a personal history?

PE I don’t write anything autobiographical. I’m private, and I hate this nonfiction shit that’s out in the world. These memoirs. Oh my God! I do not care! I’m sorry you’re dying, but I don’t care.

RS Or that your mom beat you with a two-by-four.

PE And really, if you’re writing memoirs, she ought to beat you with a two-by-four.

RS (laughter) Actually, reading your work, I could begin to trace certain commonalities, especially in terms of family. You don’t want your personal life to be the basis of a novel, but do you think that there are experiences or bits of your history, your family, that inadvertently slip out?

PE Well, I don’t know if it inadvertently slips out. I understand some things, like that of the relationship between the father and Monk in Erasure is a lot like the relationship between this old woman and the main character, David Larson, who ends up living on her ranch in my early novel, Walk Me to the Distance. But Monk’s relationship with his mother in Erasure is nothing like the relationship Suder has with his mother in my first novel. The father in Erasure is a combination of several people.

RS There are certain generalities in your work, to the point where you could say, “Well, maybe it’s drawn from personal experience.”

PE Like what?

RS Let’s just say that the mother figures are not exactly the most stable. (laughter) Like in Suder the mom is—

PE Well, she’s nuts. But she’s the only one who has sense enough to be nuts in the world in which she lives. And in Erasure the mother just has Alzheimer’s.

RS But also, in terms of personal experience coming through, generally your characters are of a particular class. They’re professionals: doctors, hydrologists, baseball players, fiction writers.

PE That’s the world I know. I know artists and I grew up with doctors. My grandfather, father, and uncles were doctors. My sister is a doctor. And I spend a lot of my time with ranchers, hydrologists, and veterinarians. Occasionally someone will say. “That’s not the Black Experience.” And I laugh and say. “I’m black, and that’s my experience.” I know a lot of black people whose experience is that, but it’s not what people want to think is the black experience—they want their black experience to be inner-city and rural south.

RS All that is the preamble to my next question, which is: How important is class to you, especially given that class tends to be conflated with race?

PE I’m a card-carrying member of the ACLU, and I go to the ballet, and I train mules and I write fiction for a living.

RS What does that mean?

PE That’s my point—it means absolutely nothing. People live in the worlds they live in, and they’re interested in the things that interest them. That’s what makes this world fascinating. I really don’t think about class. Everybody should read fiction. I think everybody should read Joyce and Ellison. I don’t think serious fiction is written for a few people. I think we live in a stupid culture that won’t educate its people to read these things. It would be a much more interesting place if it would. And it’s not just that mechanics and plumbers don’t read literary fiction, it’s that doctors and lawyers don’t read literary fiction. It has nothing to do with class, it has to do with an anti-intellectual culture that doesn’t trust art.

RS But are you sure that class doesn’t play a part? I mean, in a lot of your novels there’s a particular break where a character will come out and say. “Oh yeah, by the way, I’m black.”

PE That has nothing to do with class.

RS That’s why I brought up the intersection of race and class. That tension’s always there in your novels. Most of your main characters are black professionals to one degree or another, and there’s always that break in the work, as though to say, “What? I can’t be a professional and African American?” You relate a typical black experience, the black experience that isn’t rural or ghettoized.

PE I don’t think I’m saying that. I don’t understand it. But I guess it’s not typical.

RS Speak on that a bit more.

PE When I grew up, there were three black people on TV, and they were all porters. And so all that talk about the positive black role model that everyone wanted to see made sense because there was no other. In fiction as well. You had the inner-city novel, and the “yessir, boss” role model, and it was not the experience that anybody I knew had. I grew up where the Civil War started, in South Carolina, and I have never in my life heard someone say, “Where fo’ you be going?” (laughter) So Alice Walker can kiss my ass.

RS What does Alice Walker say about the whole thing?

PE One thing she says is that she doesn’t write for people who can read. At least, somebody said she said that, so that might be a big lie, but I would believe it given what I have read.

RS What do you think about the whole Oprah thing?

PE Oprah should stay the fuck out of literature and stop pretending she knows anything about it, in the same way that people should stop giving any credence to book reviews on Amazon.com. And people should get educated so they can read all sorts of things and have their lives and society become richer. Walt Whitman in By Blue Ontario’s Shore writes, “Produce great Persons, the rest follows.” You produce better people by having smarter people.

RS What if someone accused you of being anti-democratic? In the sense of art reaching a mass audience?

PE Give me a fucking break. Art is not democratic. Why should everybody think they can write a novel? Everybody can’t play violin. That doesn’t mean people don’t aspire to do it. That doesn’t mean you can’t have a violin and try to play it. But to think that everybody is going to be good at it, just because they want to—that’s complete idiocy! That’s why George Bush is president. Democracy has its failings, and one of them is that it allows the existence of capitalist rapists like Dick and Dubya. If you want an argument against democracy watch American Idol.

RS I asked you earlier if you consider yourself avant-garde. Have you read William Gass’s essay “The Vicissitudes of the Avant-Garde”?

PE No.

RS He lays out three types of avant-garde: the leftist, which ends up being conservative, the rightist, which ends up being reactionary, and a third type that always bites the hand that feeds it. I can see your work fitting in that last category.

PE Anybody who succeeds in this capitalistic culture making serious art isn’t necessarily biting the hand that feeds him. I mean, my God, look at Guernica. That’s a great protest work, a beautiful painting. But it takes its meaning from the ugliness that allows its creation. It achieves its power because it’s produced in a world full of ugliness. That’s the nature of protest. It’s wonderfully ironic, wonderfully weird and finally, absolutely human.

RS What is absolutely human?

PE The fact that the very thing that allows our expression of something is the thing that we hate. But we love the expression of it, so we get something from it. There are some people who wouldn’t be happy if they couldn’t complain. This world is made for them. Social injustice is not going to go away, so if you hate social injustice and love complaining about it, then this is the world for you.

RS (laughter) Do you think your work protests in any way?

PE Well, that’s not for me to say. Of course I have a feeling about it, but the work is out there. If there’s a protest in there that you can find, that’s great.

RS Erasure is a big protest.

PE Oh? (laughter)

RS Yeah, I mean, come on.

PE Glyph is almost a bigger protest than Erasure. Erasure is like describing a rattlesnake’s bite. Am I protesting rattlesnakes?

RS True, although most people would not see the protest in Glyph or commit to that protest.

PE People rally around easy things.

RS And there are some easy things to pick up on in Erasure. Isn’t satire a kind of protest?

PE Not necessarily. I’m making fun of satire as well as satirizing social policies. I mean, I shouldn’t even say this, but I write about satire.

RS So you’re satirizing satire.

PE I hate hearing it back, but in some way, yes, I’m exploiting the form.

RS Gotcha. So then there is a sort of form, or thematic, or style—

PE I’m interested in all sorts of things, and form is one of them. I don’t think meaning exists without form, and certainly form does not exist without meaning. Meaning and story come first. Story is the most important part of fiction. Without it, what’s the point? If all you care about is form, become a critic.

Percival Everett. Courtesy of Percival Everett, unless otherwise noted.

RS Let’s change tracks a little bit. You’re working on your twentieth novel now?

PE It’s around there. I can’t remember.

RS You’ve probably got two more in the hopper. Why are you so damn prolific?

PE It’s my job. I mean, if I were a plumber and I only fixed two toilets a year…(laughter)

RS Has being prolific helped or hindered you?

PE I don’t give a shit as long as I can write what I want to write. I’m not trying to get rich doing this. and I don’t care about how it’s received—I just make novels, that’s my job, that’s what I want to do, that’s what I love to do. I want to train mules, I want to fish and I want to write novels.

RS Earlier we were talking about the two-fisted writer, someone who works on one book while researching another. Do you work on two at a time?