The Memoirs of Robert and Mabel Williams: African American Freedom, Armed Resistance, and International Solidarity

by Robert and Mabel Williams

The University of North Carolina Press, 2025

[Publication date: June 17, 2025]

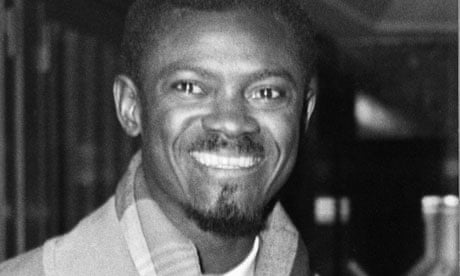

Born in Jim Crow–era Monroe, North Carolina, Robert F. Williams and Mabel R. Williams were the state’s most legendary African American freedom fighters. The Williamses' leadership in Monroe was just the beginning of a lifelong pursuit of freedom and justice for Black people in the United States and for oppressed populations throughout the world. Their activism foreshadowed major developments in the civil rights and Black Power movements, including Malcolm X’s advocacy of fighting oppression “by any means necessary,” the emergence of the Black Panther Party, and Black solidarity with Third World liberation movements.

Robert documented his experiences in Monroe in his classic 1962 book, Negroes with Guns, and completed a draft of his memoir, While God Lay Sleeping, months before his death in 1996. Mabel began a memoir of her own before her death in 2014. The family selected John Bracey Jr., Akinyele K. Umoja, and Gloria Aneb House to edit and complete the manuscripts, which are presented together in this book, offering a gripping portrait of these pioneering freedom fighters that is both deeply intimate and a fierce call to action in the ongoing fight against racial injustice.

REVIEWS:

“Breathtaking, audacious, thrilling, and a powerful testament to the unwavering commitment to Black liberation that defined the Williamses' lives, this book is a must for anyone seeking to understand the true depth of the Black freedom struggle and its relevance to today’s political landscape.”—Nkechi Taifa, Esq., author of Black Power, Black Lawyer: My Audacious Quest for Justice

“Before Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, before Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Leadership Conference, and before Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Robert and Mabel Williams were guiding us with their daily examples in Monroe, North Carolina. They showed that it is possible to live and tell the truth without shuffling and tap-dancing for the enemy. Professors Umoja, House, and Bracey have provided us with a masterwork of essential Black international knowledge.”—Haki R. Madhubuti, founder and publisher of Third World Press, author of Black Men: Obsolete, Single, Dangerous?

“The insights of the editors, established activists who were involved with the movement when the Williamses' international travel and activism was at its height, make for a truly valuable read.” —Edward Onaci, author of Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State

“These memoirs are rich with anecdotes and are crucial in helping flesh out many storylines about the Black freedom struggle. Together they offer intimate portraits of important actors and events in the United States and abroad.”—Charles Payne, author of I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle

Book Description:

Robert and Mabel Williams in their own words

ABOUT THE EDITORS:

Akinyele K. Umoja is a professor of Africana studies at Georgia State University.

Gloria Aneb House is a poet, activist, and professor emerita at University of Michigan–Dearborn and associate professor emerita in African American studies at Wayne State University.

John H. Bracey Jr. (1941-2023) was a professor of Afro-American studies at University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Capital's Grave: Neofeudalism and the New Class Struggle

by Jodi Dean

Verso, 2025

[Publication date: March 18, 2025]

The fact that communism did not prevail does not mean we are still in capitalism. Capitalist relations are undergoing systemic transformation and becoming something that might even be worse.

Bringing together analyses from different fields—law, technology, Marxism, and psychoanalysis—Jodi Dean shows the direction the contemporary world is heading: neofeudalism. Feudalism isn’t just a metaphor. It’s the operating system for the present. Politics and plunder thrive in the capitalist pursuit of profit, and the many are bound to serve the few, coerced into a system of rents, destruction, and hoarding driven by privilege and dependence.

The question is: In a society of serfs and servants, how do we get free?

With the rise of neofeudalism, and as more and more workers are drawn into the service sector—from nurses to Uber and delivery drivers—Dean argues that we can see the emergence of a new vanguard, the class that can lead the struggle for liberation from oppression and exploitation: what she calls the servant vanguard.

REVIEWS:

"A piercing look at how capitalism is killing itself as it entangles us in a web of techno-feudal power relations."

—Yanis Varoufakis, author of Technofeudalism

"Dean provides the most rigorous account of what a neofeudal society entails. Every page is a provocation, every sentence is a delight"

—Corey Robin, author of The Enigma of Clarence Thomas

"Dean’s new book gives us plenty to talk about"

—Ed Meek, Arts Fuse

"Dean’s new book delivers critical insights on humanity and society."—Ron Jacobs, Counterpunch

"Seeks to update Marx for a world that Dean thinks is starting to look less like the classical industrial capitalism he wrote about than a kind of high-tech feudalism."

—Ben Burgis, UnHerd

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Jodi

Dean teaches political theory in upstate NY where she is also actively

involved in grassroots political organizing. Raised in Mississippi and

Alabama, she went north for college, earning her BA at Princeton

University and her MA and PhD at Columbia University. Initially, her

focus was on Soviet area studies. In her second year of graduate school,

she switched to political theory, which was a good thing since the

Soviet Union ceased to exist and the field dissolved. Her books take up

questions of solidarity, the conditions of possibility for democracy,

communicative capitalism, and the necessity of building a politics that

has communism as its horizon. She has given invited lectures in art and

academic venues all over the world.

Trump's Return

by Noura Erakat, Robin D.G. Kelley, and David Austin Walsh

Boston Review, 2025[Publication date: March 18, 2025]

Donald Trump is back in the White House. Boston Review issue Trump’s Return explores how he got there, what’s next, and how to resist, featuring David Austin Walsh, Robin D. G. Kelley, Noura Erakat, Marshall Steinbaum, Jeanne Morefield, and more.

Walsh takes us inside Trump’s motley coalition of tech billionaires and “America First” nativists, examining its crackups and assessing its strength. With the right’s strategy of anti-“wokeness” now effectively spent, will these alliances hold? Steinbaum reads Bidenomics in light of the long arc of Democrats’ economic policy since the Great Recession, finding that it neglected the biggest problem: inequality. And Morefield exposes the lie at the heart of MAGA’s “invasion” narrative about the fentanyl crisis, showing how decades of bipartisan fixation on enemies abroad―and denial of the exceptional savagery of capitalism at home―have led to this moment.

Looking forward, Erakat follows the imperial boomerang from Palestine as it deepens political repression in the United States; Kelley plots a revival of class solidarity as the only path to durable and meaningful resistance; plus more on the colossal scale of money in politics, the labor vote, and the promises and perils of progressive federalism.

The issue also includes Gianpaolo Baiocchi on lessons from Lula’s extraordinary success in building a workers’ party in Brazil, Joelle M. Abi-Rached on the trauma of political violence and Syria’s future after the fall of Assad, Aaron Bady on the right’s resurgent natalism and liberal panic about falling birthrates, and Samuel Hayim Brody on the reality of settler colonialism and the mystifications of Adam Kirsch.

We All Want To Change The World: My Journey Through Social Justice Movements From the 1960s To Today

by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Raymond Obstfeld

Crown, 2025

[Publication date: May 13, 2025]

A

sweeping look back at the protest movements that changed America from

activist and NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, with personal and

historical insights into lessons they can teach us today

“A compelling case for standing up for justice at a time when everything, it seems, is on the line.”—Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

For

many, it can feel like change takes too long, and it might seem that we

have not moved very far. But political activist Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

believes that public protest is a vital part of affecting change, even

if that change doesn’t come “right now.”

In We All Want to Change the World,

he examines the activism of people of all ages, ethnicities, and

socio-economic backgrounds that helped change America, documenting

events from the Free Speech Movement through the movement for civil

rights, the fight for women’s and LGBTQ rights, and, of course, the

protests against the Vietnam War. At a time in our history when we are

witnessing protests across campuses, within the labor movement, and

following the killing of George Floyd, Abdul-Jabbar reminds us that

protests are a lifeblood of our history:

“Protest movements, even

peaceful ones, are never popular at first. . . . But there is a reason

protest gatherings have been so frequent throughout history: They are

effective. The United States exists because of them.”

Part history lesson and part personal reminiscences of his own activism, We All Want to Change the World will resonate with anyone who recognizes the need for social change and is willing to do the work to make it happen.

REVIEWS:

“Here, Kareem Abdul’s-Jabbar exhibits the retrospective vision of a historian, the analytical discipline and clarity of a social scientist, and the passion and compassion of the life-long social change activist that he has been.”—Harry Edwards, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus: Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley

“Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has never shied away from using the fame he achieved through his transcendent basketball talents to speak out about critically important issues, particularly around equality and social justice. The perspectives he shares in this book reflect his decades of activism and his hunger to inspire others to stand up for what is right.”—Adam Silver, NBA Commissioner

“With wisdom, compassion, and humility, this book reminds readers that the ideals of equality and justice are works in progress that each generation is tasked with transforming into reality. A timely reflection on protest movements that also chronicles how a beloved champion came to political consciousness.”—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar changed the game of basketball with his breathtaking feats on the court. Just as important, he used his voice off the court to speak out for social justice in ways that would have made his hero Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., proud. We All Want to Change the World is an inspiring book that reflects the inspired life and work of the revolutionary author behind its every page.”—Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor, Harvard University

“As accomplished as Kareem was as an athlete, what I respect and appreciate about the legendary big fellow is his ongoing fight for social justice. Kareem, like Nelson Mandela, fights for all people to be treated fairly and to be given a chance to achieve their dreams. It’s this unwavering commitment to fairness and human dignity that makes me deeply admire and respect his ongoing efforts beyond the basketball court.”—Robert Parish, former Boston Celtics player

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is one of the greatest basketball players of all time as well as a committed social justice champion and award-winning writer. He is the New York Times bestselling author of seventeen books, an award-winning documentary producer, and a twice Emmy-nominated narrator. He is the recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, The Lincoln Medal, The Rosa Parks Award, the U.C. Presidential Medal, and Harvard University’s W. E. B. Dubois Medal of Courage. He holds nine honorary doctorate degrees and is a U.S. Cultural Ambassador. Currently, Abdul-Jabbar serves as the chairman of Skyhook Foundation, bringing educational STEM opportunities to underserved communities.

Raymond Obstfeld is an American novelist, screenwriter and non-fiction writer. He teaches creative writing at Orange Coast College.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1

The Free Speech Movement: “I’m Gonna Say It Now”

Oh, I am just a student, sir, and only want to learn

But it’s hard to read through the risin’ smoke of the books that you like to burn

So I’d like to make a promise and I’d like to make a vow

That when I’ve got something to say, sir, I’m gonna say it now

Phil Ochs, “I’m Gonna Say It Now”

So, what exactly are we talking about when we talk about free speech? The free speech movement that launched in 1964 at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) was ground zero for most student activism of the sixties and seventies. Before this unprecedented campus uprising, the country’s interest in free speech could best be described as the proverbial three wise monkeys who “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” When it came to issues like civil rights and the war in Vietnam, it was as if most the country were on mute. The public’s sphinxlike reserve was so pronounced that President Nixon declared the silence a badge of honor: “And so tonight—to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans—I ask for your support.”

While that “silent majority” emulating the shy monkeys may have seen their passive support of authority as honorable behavior, those looking to extend personal, social, and political freedoms saw it as an abnegation of duty—and saw this unengaged segment of the public, remaining in their La-Z-Boys clutching the television remote, as cowardly, the only change they tolerated being that between channels showing Bewitched and Gilligan’s Island. For a few years, silent majority became a popular pejorative used by activists to shame the uninvolved. The term remained fairly dormant after the 1970s, but like a pesky cold sore, it reemerged in 2020, again as a call for conservative support, when Donald Trump found his inner Nixon and tweeted, “THE VAST SILENT MAJORITY IS ALIVE AND WELL!!!” Perhaps. But Trump lost the election by about 7 million votes. The majority broke their silence at the voting booth. Unfortunately, in 2024, in a backlash against the noise of progressive change, the silent majority voted Trump back in to silence others who spoke out for equality.

The free speech movement is unlike all the other protest movements in our history because free speech is so difficult to define. Can a server wear a Christian crucifix while working in a Muslim diner? Or a swastika while working at a Jewish deli? Can a white person publicly sing the N-word in a song written by a Black person? Can a ticket taker at a movie theater wear a button promoting a political candidate? Can a school force children to recite the Pledge of Allegiance? Can a pharmacist refuse to sell birth control pills if they are contrary to his religious beliefs? These are the kinds of questions we struggle to answer when defining the boundaries of free speech.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution doesn’t offer much help. Not only is it frustratingly brief, but it includes several major rights in the same sentences: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” We are left to debate what constitutes “abridging”—which we have been vigorously and acrimoniously doing since the amendment was ratified in 1791. We are also made aware that the amendment refers only to the government restricting free speech, not all entities, including private businesses. The one thing most of us agree on: There is no such thing as absolute free speech in which anyone can say anything to anyone at any time. Our challenge for the past 230 years has been to make a distinction between what’s truly harmful and what’s merely offensive.

For example, the 1974 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Smith v. Goguen struck down the conviction of a teenager who had worn a small American flag patch on the back pocket of his jeans. At the time of his arrest, he was not involved in any protest; nor was he blocking traffic. He was merely chatting on the street with friends. The original jury found him guilty of flag desecration, and the judge sentenced him to six months in jail. Why was he arrested in the first place? Because the police took offense at the location of his flag at a time when anti-establishment protests were still popular across the country.

Though the case was decided based on the vagueness of the law, the real issue was freedom of speech. Clearly, Goguen’s flag was interpreted by the police as stating a political opinion that offended the arresting officer. Ironically, had Goguen said the words “This country sucks,” the police wouldn’t have been able to arrest him. But the simple patch on his back pocket was a provocative scream in their faces. To the police, it was akin to his wordlessly giving them middle finger. The cops chose to interpret the patch as negative political commentary when it could just as well have been a sign of patriotism or merely a design choice. Today, designer Ralph Lauren sells an entire line of clothing featuring the American flag, including on pants. This is how the limitations of free speech evolve. One decade’s deep personal offense is another decade’s profitable commerce.

Our inability, or unwillingness, to put aside our personal biases and emotional triggers is what makes the discussion of free speech so difficult. Nevertheless, that is our mandate as American citizens. That’s what social critic Noam Chomsky meant when he said, “If you’re in favor of freedom of speech, that means you’re in favor of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise.”

There are necessary restrictions. We’re all familiar with slander and defamation laws that prohibit us from saying untrue things that damage a person or company. Three major cases in the past couple of years illustrate how necessary this restriction on free speech is, not just for individuals, but for the entire country.

In October 2022, a jury ordered Infowars founder Alex Jones to pay $965 million to the families of eight victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, which took twenty-six lives. Jones’s years of broadcasting lies about the 2012 shooting—that it was a hoax and that the parents of the dead were paid actors—had done severe emotional damage to the families, who endured relentless online harassment and death threats. This decision helped place limits on the ability of conspiracy theorists to hide behind a journalistic free press while saying whatever they wanted, despite the harm it caused.

In April 2023, Fox News settled a defamation lawsuit for $787.5 million for having deliberately spread lies about the 2020 presidential election.

And in December 2023, former New York City mayor and Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani was ordered to pay $148 million for defaming two election workers, a mother and daughter, by accusing them of ballot tampering. He offered no evidence to support this claim, yet both women were targeted with threats of violence and death. They continued to be threatened even after they won their case against him.

The criminal acts behind all three of these cases were politically and financially motivated and were aimed at an audience already skeptical of government interference and, therefore, easy to goad with lies. Jones claimed that the Sandy Hook massacre had been staged in order for the government to confiscate private citizens’ guns, a dog whistle issue among conservatives that helped him earn more than $165 million over three years. His legacy for those years—aside from the pain he caused grieving parents—was to stir suspicion and resentment against the U.S. government.

In some ways, Fox News’s and Giuliani’s misdeeds were even worse. They acted like the guy in old Western movies who buys drinks for everyone in the saloon and then, when they’re liquored up, whips them into a frenzied mob to go lynch the kid in the jailhouse—all the while knowing the kid is innocent because the mob leader himself is the actual killer. The constant lies about election fraud have had a long-term and dangerous effect on the country because they undermine the integrity of the presidential election.

Trusted elections are the foundation of democracy. When the people don’t trust elections to be fair, they feel they can’t trust the government on anything. At that point, democracy dies. And if democracy in the United States falters, then democracies around the world will be weakened and may also crumble. Worse, both Giuliani and Fox News did what they did for money. Fox, for its part, was trying desperately to win back its declining audience, who felt the network wasn’t conservative enough. And Giuliani was trying to stay on Donald Trump’s good side—which seemed to work, because in September 2023, Trump hosted a $100,000-a-plate dinner to raise money for his former lawyer.

In none of these cases was the guilty party stifled from saying whatever they wanted. All the lawsuit asked them to do was offer evidence that their accusations were truthful. None could. In lawsuits like these, free speech was not being harmed—quite the opposite. These cases demanded only that free speech not be unjustly or inaccurately used as a weapon against innocent people or the country.