"Remember that consciousness is power. Consciousness is education and knowledge. Consciousness is becoming aware. It is the perfect vehicle for students. Consciousness-raising is pertinent for power, and be sure that power will not be abusively used, but used for building trust and goodwill domestically and internationally. Tomorrow’s world is yours to build.”

-- Yuri Kochiyama, 1921-2014

All,

For over fifty years the renowned and much beloved Japanese American human rights activist and community organizer Yuri Kochiyama, who passed away last week at age 93, made a major and enduring contribution to one of the most important and truly transformative eras in the history of radical/progressive political and cultural activism in the United States. In many ways the world historical arc of Yuri's extraordinary life over the past century epitomizes the courageous emergence of radical women in particular and people of color generally as the foremost revolutionary forces in American society and culture. In Kochiyama's case this was accomplished through an always deeply humble and compassionate stance that was simultaneously highly disciplined and fully committed to critical thought and action on a multitude of levels. Her close and fastidious attention to the complicated and contentious dynamics of race, class, and gender proved especially valuable in a deeply polarized white and male supremacist society and culture that existed within the larger hegemonic context of national and global structures of capitalist domination and control.

For over fifty years the renowned and much beloved Japanese American human rights activist and community organizer Yuri Kochiyama, who passed away last week at age 93, made a major and enduring contribution to one of the most important and truly transformative eras in the history of radical/progressive political and cultural activism in the United States. In many ways the world historical arc of Yuri's extraordinary life over the past century epitomizes the courageous emergence of radical women in particular and people of color generally as the foremost revolutionary forces in American society and culture. In Kochiyama's case this was accomplished through an always deeply humble and compassionate stance that was simultaneously highly disciplined and fully committed to critical thought and action on a multitude of levels. Her close and fastidious attention to the complicated and contentious dynamics of race, class, and gender proved especially valuable in a deeply polarized white and male supremacist society and culture that existed within the larger hegemonic context of national and global structures of capitalist domination and control.

Despite

these pervasive and entrenched structural and institutional barriers

to human liberation Yuri insisted on communicating and rising above and

beyond these self imposed and divisive boundaries of ethnicity, culture,

and traditional notions of social identity. Rather she insisted upon

and remained an active and tireless advocate of unity and struggle

across these barriers. It was this open ended appreciation of, and

fervent yet mature immersion in, an authentic multicultural,

multiracial, and multinational consciousness that made Yuri Kochiyama

the outstanding human being and social revolutionary that she was, and

via her tremendous ongoing legacy of creativity and transformation

through struggle and engagement, still remains. This special issue of

the Panopticon Review and the many various statements and analyses about

her and her work is dedicated to expressing our deeply heartfelt love

and steadfast appreciation for what she has given all of us through the

great strength and exemplary force of her example. May Yuri rest in

eternal peace and power for she has certainly earned it as well as our

deepest respect, admiration, and support, always and forever. Thank you

Yuri for everything you've done and tried to do in a stunningly

beautiful and truly useful and inspiring life that gives us all great

faith in our collective future and what we can and must do to celebrate,

struggle for, and reclaim our lives in society as truly liberated human

beings .

In Love and Struggle

A Luta Continua/The Struggle Continues,

Kofi

“The movement is contagious, and the people in it are the ones who pass on the spirit.” -Yuri Kochiyama, From documentary Yuri Kochiyama: A Passion for Justice (1993). Directed by Rea Tajiri and Pat Saunders.

Of Land and Liberation, Decolonization and Dignity:

Remembering Yuri Kochiyama

By Diane C. Fujino

"For a colonized people, the most essential value, because it is the most meaningful, is first and foremost the land: the land, which must provide bread and, naturally, dignity."

--Frantz Fanon

The

Panoptican Review’s extension of Afro-Asian solidarity--its tributes to

Yuri Kochiyama on her birthday on May 19 and following her passing on

June 1--epitomizes one of her foremost qualities. Yuri is one of the

strongest models we have of bridge building, of unifying difference

across borders. I first met her in late 1995, when I traveled to New

York to interview her for what I thought would be a study on Asian

American women’s activism. Yuri was a captivating and compelling

narrator of the multiple radical movements in which she was working.

Despite her humility in minimizing her own contributions, it was easy to

discern that she was in the thick of the vibrant Black, Asian, and

Puerto Rican freedom movements in and around Harlem. I was overwhelmed

by her history and felt the need to learn more about her life. I am

honored and humbled to have been able to research and write her

biography, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri

Kochiyama.

After

meeting Malcolm, Yuri underwent a process of decolonization, not unlike

what Frantz Fanon describes in Wretched of the Earth. She moved from a

place of pacification to a space of liberation. At their first meeting

in October 1963, Yuri was surprised she had criticized Malcolm for his

“harsh stance on integration.” She was equally surprised at his gentle

and patient response and his invitation to attend the Liberation School

of his Organization of Afro-American Unity. Soon every Saturday morning

Yuri was learning new knowledge and new analyses.

Yuri was remarkably open-minded. She was willing to listen and learn from people whose experiences differed from her own. Still, had she been the provincial and apolitical twenty-something year old inside the concentration camps, these ideas wouldn’t have made sense to her. It was her incarceration experience that first awakened a budding and uneven awareness of racism. She wrote in her camp diary in May 1942: “It’s strange. I never felt like this before…. I never thought of myself as being a part of a nation so prejudiced....[I never] thought of people according to their race, but just that they were individuals. I want to keep thinking that way; that we’re all Americans here, if we feel it in our hearts; that we’re all individuals.” But in the postwar years she learned about anti-Black racism from her neighbors in a midtown Manhattan housing project, from her customers in the working-class establishments in which she waitressed, and from viewing televised images of fire hoses and police dogs attacking civil rights protesters. After 1960, when her family moved to Harlem—not for any political reasons, but for a larger housing project unit—Yuri, her husband Bill, and their six children got involved in the political issues encircling them in this pulsating Black community. By the time she met Malcolm, the accumulation of historic events and her personal experiences had readied her to hear Malcolm’s provocative and transgressive proclamations.

From her first class at the OAAU Liberation School, when the instructor connected Asian martial arts with Black culture and spirituality, Yuri noticed the expression of Afro-Asian solidarity within what was considered a Black separatist organization. She learned from Malcolm and his associates how colonial Europe divided Africa without regard to cultural or geographic boundaries. She listened to a recording of Fannie Lou Hamer describing her jailing where a prison guard forced two Black prisoners to beat her half to death. She heard Malcolm condemn the hypocrisy of the government demanding non-violence from Blacks in Mississippi, while the US waged a war of violence in Korea. One of the most important lessons she learned was of the significance of land, for providing food and the material basis of nation and community building—and for dignity. She joined the Republic of New Africa, which envisioned liberation through the establishment of a Black nation on land in the US South. She became a fierce supporter of political prisoners, many of whom were targeted for their revolutionary nationalist/internationalist struggles for land and liberation. She defended Puerto Ricans imprisoned for their struggles for national sovereignty. She denounced US and Japanese colonialism from Hiroshima to Okinawa, from Vietnam to Hawaii. She worked with Asian Americans for Action in New York and became a respected leader of the nationwide Asian American Movement. She came to support Robert F. Williams and learned of the Black contingents that visited revolutionary Cuba. She herself would later travel to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade. She also went with a delegation to Peru to protest the imprisonment of the communist leader of the Shining Path. She called for Black reparations alongside Japanese American redress. And after moving to Oakland in 1999, she became an outspoken critic of the US war in the Middle East, connecting her opposition to US militarism in Iraq and Afghanistan with her earlier support for Palestine and Libya.

Throughout her decades of activism, Yuri worked for, as Frantz Fanon wrote, that the minimal demand of decolonization is that “the last become the first.” Yuri consistently saw as most crucial the liberation of the most oppressed. She prioritized the struggles for political prisoners and poor communities of color, and saw her work as part of the worldwide decolonization movement against racism, imperialism, and capitalism.

Yuri was remarkably open-minded. She was willing to listen and learn from people whose experiences differed from her own. Still, had she been the provincial and apolitical twenty-something year old inside the concentration camps, these ideas wouldn’t have made sense to her. It was her incarceration experience that first awakened a budding and uneven awareness of racism. She wrote in her camp diary in May 1942: “It’s strange. I never felt like this before…. I never thought of myself as being a part of a nation so prejudiced....[I never] thought of people according to their race, but just that they were individuals. I want to keep thinking that way; that we’re all Americans here, if we feel it in our hearts; that we’re all individuals.” But in the postwar years she learned about anti-Black racism from her neighbors in a midtown Manhattan housing project, from her customers in the working-class establishments in which she waitressed, and from viewing televised images of fire hoses and police dogs attacking civil rights protesters. After 1960, when her family moved to Harlem—not for any political reasons, but for a larger housing project unit—Yuri, her husband Bill, and their six children got involved in the political issues encircling them in this pulsating Black community. By the time she met Malcolm, the accumulation of historic events and her personal experiences had readied her to hear Malcolm’s provocative and transgressive proclamations.

From her first class at the OAAU Liberation School, when the instructor connected Asian martial arts with Black culture and spirituality, Yuri noticed the expression of Afro-Asian solidarity within what was considered a Black separatist organization. She learned from Malcolm and his associates how colonial Europe divided Africa without regard to cultural or geographic boundaries. She listened to a recording of Fannie Lou Hamer describing her jailing where a prison guard forced two Black prisoners to beat her half to death. She heard Malcolm condemn the hypocrisy of the government demanding non-violence from Blacks in Mississippi, while the US waged a war of violence in Korea. One of the most important lessons she learned was of the significance of land, for providing food and the material basis of nation and community building—and for dignity. She joined the Republic of New Africa, which envisioned liberation through the establishment of a Black nation on land in the US South. She became a fierce supporter of political prisoners, many of whom were targeted for their revolutionary nationalist/internationalist struggles for land and liberation. She defended Puerto Ricans imprisoned for their struggles for national sovereignty. She denounced US and Japanese colonialism from Hiroshima to Okinawa, from Vietnam to Hawaii. She worked with Asian Americans for Action in New York and became a respected leader of the nationwide Asian American Movement. She came to support Robert F. Williams and learned of the Black contingents that visited revolutionary Cuba. She herself would later travel to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade. She also went with a delegation to Peru to protest the imprisonment of the communist leader of the Shining Path. She called for Black reparations alongside Japanese American redress. And after moving to Oakland in 1999, she became an outspoken critic of the US war in the Middle East, connecting her opposition to US militarism in Iraq and Afghanistan with her earlier support for Palestine and Libya.

Throughout her decades of activism, Yuri worked for, as Frantz Fanon wrote, that the minimal demand of decolonization is that “the last become the first.” Yuri consistently saw as most crucial the liberation of the most oppressed. She prioritized the struggles for political prisoners and poor communities of color, and saw her work as part of the worldwide decolonization movement against racism, imperialism, and capitalism.

* * *

"I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind then that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it; and while there is a criminal element, I am of it; and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free."

--Eugene Debs

Despite her historic contributions and the huge admiration given to her from Black radicals, Asian American activists, the young and the old, Yuri always saw herself as standing among the people, no better than anyone else. Like any other person working with dogged determination, Yuri struggled between the rhythm and urgent demands of, as Yuri liked to say, “The Movement,” and of everyday family life. Yuri had a long history, dating back to her teen years, of opening her home for social events and to people who had no place to stay. In the 1950s, she and her husband Bill held social gatherings every Friday and Saturday night. Upwards of 100 people crowded into their small apartment, about half strangers. In the 1960s, their apartment became filled with Black Power activists and political meetings and events. This wasn’t always easy on her children, who struggled to find privacy or who might find a guest sleeping in their beds if they returned home late. So Yuri has received criticism. Yet, male activist leaders rarely face the same scrutiny. We still place the responsibilities of family and home disproportionately onto women, and because Yuri integrated her family and activism in ways that men often don’t, this inadvertently invited such questioning.

Throughout her six decades of unrelenting activism, Yuri worked to attend to and nurture the individual—in prison, in the Movement, in need—while also struggling to build a better society. However imperfect and marked by human contradictions, Yuri is a model of connecting the collective and the individual, social structure and human agency. I’ve witnessed Yuri emerging from a stormy meeting filled with contentious discussions about theory and strategy only to ask people on multiple sides of the debates about their families or a specific happening in their lives. Yuri wasn’t afraid to take hard political stands, and did so repeatedly, but she also saw the need to affirm the humanity in each of us, to see us in our strengths and our struggles, and to see the collectivity that binds us together as we work to create a liberatory society. She recognized that we’re all in a process of transformation, and that, as Frantz Fanon articulated, “[t]he ‘thing’ colonized becomes a man [or woman or full human being] through the very process of liberation.”

Yuri, I thank you for being my foremost political mentor and precious friend, and for teaching me about the need to affirm the dignity of each individual and to do so through a process of decolonization.

Diane C. Fujino is the author of various books on Afro-Asian radicalism, including Heartbeat of Struggle on Yuri Kochiyama, Samurai among Panthers on Richard Aoki, and Wicked Theory, Naked Practice on Fred Ho. She is Professor of Asian American Studies and Director of the Center for Black Studies Research at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Inspired by Yuri, she’s a longtime activist in the political prisoner, anti-war, public education, and Asian American movements.

In Memory of Yuri Kochiyama

by C.N.

by C.N.

June 5, 2014

The Color Line

You

may have heard that long-time civil rights activist and Asian American

icon Yuri Kochiyama passed away earlier this week at the age of 93.

Readers can learn more details about her amazing life through boted

Asian American scholar Diana Fujino’s biography Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Prominent Asian American blog Reappropriate also has links to several other articles from major media outlets about her passing.

The

biography and articles highlight how she grew up in the Los Angeles

area and had a seemingly normal middle-class life. All of that changed

after the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

As history records, this eventually resulted in 120,000 Japanese

Americans (two-thirds of them being U.S. citizens) having their

constitutional rights revoked and incarcerated, just based on their

Japanese ancestry, in dozens of prison camps across the U.S., without

any due process whatsoever.

Among

those imprisoned were Yuri and her family and this experience forever

changed her perspective on the state of race relations, racism, and the

overwhelming need for social justice in the U.S. She eventually married a

Japanese American GI and moved to Harlem, New York City. There, she

befriended a young Black nationalist named Malcolm X and in the course

of her friendship, galvanized her determination to work toward social

equality and justice on behalf of her community. She was there when

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965.

Thereafter,

she became known for actively participating in the movements for ending

the Viet Nam War, Puerto Rican independence (highlighted by being part

of the group that occupied the Statue of Liberty in 1977), and for

Japanese American reparations. In her later years in Oakland, CA, she

kept up her activism and social justice work, particularly around the

fight against racial profiling and rounding up of Arab and Muslim

Americans in the aftermath of 9/11, as detailed in the excellent

documentary “Lest We Forget” that highlighted the similarities between

Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor and Arab & Muslim

Americans after 9/11. Here at my institution, the University of

Massachusetts, Amherst, our Asian American student center is named the

“Yuri Kochiyama Cultural Center” on her behalf.

For me

personally, Yuri Kochiyama was a hero and an inspiration. Like Yuri, I

grew up in a predominantly White community and was entrenched in an

assimilationist environment. I did not care about my roots as an Asian

American, an immigrant, or a person of color — I just wanted to fit in

and be like everybody else around me. In doing so, I was ignorant of all

the racial injustices that had been perpetrated against people like me

throughout U.S. and world history and that was still taking place all

around me in different ways.

It wasn’t until my later years in college and after I started studying Sociology and Asian American Studies that I finally woke up, opened my eyes, reclaimed my identity, and pledged myself to do what I could to fight for racial equality and justice. That’s when I first learned about Yuri Kochiyama. She represented not just someone who was determined to draw on her personal experiences of racism to fight on behalf of others in similar situations, but as an Asian American woman, she stood in stark contrast to the stereotypical images of Asian American women as meek, submissive, exotic, and hypersexualized “geishas” and “China dolls.”

It wasn’t until my later years in college and after I started studying Sociology and Asian American Studies that I finally woke up, opened my eyes, reclaimed my identity, and pledged myself to do what I could to fight for racial equality and justice. That’s when I first learned about Yuri Kochiyama. She represented not just someone who was determined to draw on her personal experiences of racism to fight on behalf of others in similar situations, but as an Asian American woman, she stood in stark contrast to the stereotypical images of Asian American women as meek, submissive, exotic, and hypersexualized “geishas” and “China dolls.”

In other words, she gave all of us — men and women, Asian American or not — a different example of what Asian Americans, particularly women, are capable of. It is these examples and memories of Yuri Kochiyama as a strong, determined, committed, and inclusive activist and Asian American woman that I will carry forth with me.

Mountains That Take Wing

Thirteen years, two inspiring women, both radical activists – one conversation.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJik3l2vb1g

About the Film

Angela Davis & Yuri Kochiyama in an inspiring, historically rich and unique documentary featuring conversations that span thirteen years between two formidable women who share a profound passion for justice.

Through conversations that are intimate and profound, we learn about Davis, an internationally renowned scholar-activist and 88-year-old Kochiyama, a revered grassroots community activist and 2005 Nobel Peace Prize nominee. Their shared experience as political prisoners and their dedication to Civil Rights embody personal and political experiences as well as the diverse lives of women doing liberatory cultural work.

Illustrated

with rarely-seen photographs and footage of extraordinary speeches and

events from the early 1900s to the ’60s and through the present, the

topics of this rich conversation range from critical, but often

forgotten role of women in 20th century social movements to the

importance of cross-cultural/cross-racial alliances; from America’s WWII

internment camps to Japan’s “Comfort Women”; from Malcolm X to the

prison industrial complex; and from war to cultural arts. Davis and

Kochiyama’s comments offer critical lessons for understanding our

nation’s most important social movements while providing tremendous hope

for its youth and the future.

Directed, produced, photographed, recorded & edited by C. A. Griffith & H. L. T. Quan, along with Co-editor Paul Hill, this documentary was completed through a prestigious, Art & Technology post-production residency award at Wexner Center for the Arts (2009-2010). Mountains that Take Wing is distributed by Women Make Movies and available for you to buy or rent.

Participant Biographies

Yuri's activism started in Harlem in the early 1960s, where she participated in the Harlem Freedom Schools, and later, the African American, Asian American and Third World movements for civil and human rights and in the opposition against the Vietnam War. In 1963, she met Malcolm X. Their friendship and political alliance radically changed her life and perspective. She joined his group, the Organization of Afro-American Unity, to work for racial justice and human rights. Over the course of her life, Yuri was actively involved in various movements for ethnic studies, redress and reparations for Japanese Americans, African Americans and Native Americans, political prisoners' rights, Puerto Rican independence and many other struggles.

Yuri is survived by her living children -- Audee, Eddie, Jimmy and Tommy, grandchildren -- Zulu, Akemi, Herb, Ryan, Traci, Maya, Aliya, Christopher, and Kahlil and great-grandchildren -- Kai, Leilani, Kenji, Malia and Julia."

Yuri Kochiyama's stint as a scholar in residence at UCLA in 1998 enriched the life of our Center and the campus. Those connections deepened as we were honored to work with her on the publication of her memoir, Passing It On (UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2004). The Center is also honored to house some of Yuri Kochiyama's papers relating to the Asian American movement. We are grateful to be part of preserving her legacy for future generations.

Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014) was a Japanese American activist who organized and fought for the liberation of all people. Her life & work continue to illuminate & inspire generations of organizers working for justice in the U.S. & around the world. This is how we choose to remember her & honor her legacy.

Please join us.

Attorney (by way of community and political activism)

Yuri was one of the first activist Asian Americans I met as a college student in 1970. I had the privilege and honor of working with her to develop and organize Asian American resistance to the war in Vietnam, we marched together in Washington and NYC. She was an inspiration to many of us in rediscovering the hidden history of political and social struggle of Asian America. Through many of the dark early days her constant strength, wisdom and compassion helped me keep my own. Because she stayed the course in a lifelong crusade for human rights and dignity I was able to make and maintain my modest contribution in the same crusade.

Thank you, Yuri for being there for me, for us. You will be missed but never forgotten.

Johann Lee

6 days ago

“A Constant Communicator, Constant Facilitator, Constant Networker”: Yuri Kochiyama, the Centerwoman Activist

This past spring, I wrote about Yuri Kochiyama for my senior honors thesis through the American Studies department at the University of California, Berkeley. I decided to write about the political activism of Yuri Kochiyama as an effort to challenge the Black-White racial paradigm that pervades the American mentality. I believe that by discussing stories of solidarity among ethnic minorities, we begin to understand the power of cross-racial collaboration and resist the racial categorization and separation enforced by white supremacy. Although I never met Yuri, I felt inspired and encouraged as I listened to interviews, watched documentaries, and read countless accounts of her brave, passionate work with underrepresented communities of color throughout her life. For this blog entry, I would like to share a portion of my thesis, which articulates her passion, hard work, and dedication to her community and the Black liberation movement:

“In the heat of the nationwide turn towards revolutionary politics and radical activism, Yuri Kochiyama developed her role as a “centerwoman,” an activist who is not a highly visible traditional leader like a spokeswoman, but nonetheless an important leader doing necessary “behind-the-scenes” work and providing stability to a social movement. A centerwoman directs her energy and passion for social change towards bringing people together, creating social awareness through personal conversations, and transmitting information through wide social networks. Kochiyama was able to embrace her role as a centerwoman in the Black community by joining or becoming an ally of many newly founded Black liberation organizations. Malcolm X’s death was a tragedy and an immeasurable loss to humanity. People across the globe were angry, saddened, and devastated. However, Black activists were also inspired by his legacy and founded Black nationalist, liberationist groups such as the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BART/S), and the Republic of New Africa (RNA). From her involvement with these organizations, Kochiyama was able to develop deeper and wider connections with more members of the Black struggle. Kochiyama, who knew countless people, from famous Black leaders to friends of friends, became the human equivalent of a social encyclopedia. One RNA activist recalled:

“Yuri used to waitress at Thomford’s. That became like our meeting place. Everybody would come in and talk to Yuri. So when you come in, Yuri would have the most recent information for you. If we wanted to set up a meeting, she would set it up. If you had a message for someone, you’d just leave it with Yuri She must have received fifteen, twenty messages a day.”

Kochiyama had a wide reputation for being reliable and active in the movement. Whether she was writing articles for movement publications, attending protests and demonstrations, or handing out leaflets for organizations, people knew they could depend on Kochiyama to acquire or disseminate important information. Kochiyama even held open houses on Friday and Saturday nights at her home where activists could congregate and discuss revolutionary ideas directly among themselves. Since the 1950’s, Kochiyama had always opened her home to friends and strangers alike who needed a place to stay. From famous activists like SNCC and BPP leader Stokely Carmichael, poet and BART/S founder Amiri Baraka, and OAAU leader Ella Collins, to small children, guests from different backgrounds and perspectives felt her hospitality, generosity, and kindness in her oftentimes crowded, but nonetheless welcoming home.[i]”

[i] Diane Fujino. “Grassroots Leadership and Afro-Asian Solidarities: Yuri Kochiyama’s Humanizing Radicalism.” In Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 300-304

Hannah Hohle is a recent graduate from the University of California Berkeley and is now pursuing her career as an educator through the Urban Teacher Center in Washington, DC.

6 days ago

Teddy bears in Harlem

I visited Yuri and Bill in 1992 in their apartment in Harlem. The sofa where we sat was covered with dozens of cute little stuffed bears. On the walls were plaques and thank you messages from the Black community, at least one of them mentioning Malcolm X. I was there to learn about their history and perspectives on Asian American movement organizing. Years later I saw her give talks in different places and paying so much attention to everyone who approached her. She would ask for your name and record it in her little book, and then ask you all kinds of things about what you thought as if she were really learning from you. She was kind and strong and committed: one of a kind woman.

Karin Aguilar-San Juan is the editor of The State of Asian America: Activism & Resistance in the 1990s, published by South End Press

1 week ago

Remembering Yuri

Anne K. Johnson

1 week ago

Yuri & William’s son, Billy was a civil rights worker in Mississippi in the 1960’s, as was I. Yuri and my father became friends as part of a grouping of parents of civil rights workers. And that’s how I met Yuri.

Yuri was totally dedicated to ending class exploitation, and, as well, used her experience with internment to fight every battle she could to fight national and racial oppression. She was gentle and yet a warrior, an intellectual and a student.

I chaired the New Jewish Agenda in the late 1980’s/early 1990’s. Yuri was proud of our support of justice for the Palestinian people…I loved Yuri. Honor to her memory, and power to the people.

Ira Grupper, Louisville, Kentucky

1 week ago

From Dr. Mutulu Shakur to Nobuko Miamoto

Nobuko,

From your last discussion concerning your visit to Yuri I yearned for her to be free, something that we do not like to say to each other. But most of my life Yuri’s spirit has been a comforting factor in all matters to our lives in struggle. A true ally and sister, friend and comforter. The last stages of her mental capacity must have been a task for her to comprehend. But knowing her and the many agendas she entertained, no thought, no statement, no directive did not have a precise objective. She was a person with a driving thirst to accomplish, and in her next life we better get on our p’s and q’s. She will be guiding our lazy spirits that yearn for rest. We must answer Yuri’s call and her example of a thriving spirit in all stages of existence.

She called my name and remembered my love for her. I am thankful. For me it’s an affirmation of the role she will play in my life at her next stage. I will always love her and remember her. Hear from you later Yuri. Enjoy the ride. I see your beautiful smile already.

Fate is a strange and twisted fiber that runs through the material of our lives. The inevitable meeting between Yuri and I was not by chance. The combined destiny of our lives, at least for me, was spiritual. We followed each other in a dynamic evolution. I benefited extraordinarily from sister Yuri’s sacrifices and audacity in the struggle.

She became a bridge to her world that I did not know. I began to see through her eyes, meeting brothers and sisters of I Wor Kuen, discovering acupuncture from her introduction. And she followed me to places, unbeknownst to my then young mind, in search for the truth. As part of the Republic of New Africa, we went together to Mount Bayou Mississippi to El Malik. She followed to help me watch my steps, never untangling or disloyal to our collective fate.

I’m not missing you Yuri, for you are within me. Your life has set a standard with which solidarity is built. There are very few in the world that can compare a lifestyle I committed myself to over these years to give honor to your mentorship. I’m so thankful for your example. Much of what our struggle has accomplished, you have been a driving force. I am so thankful.

I take the prerogative to thank you for the many who are waiting for you in the universe, and the many who are unaware of your transition. We love you so very dearly. I will continue to follow your example, and spread that special love for life and justice all over the world.

It is said that still waters run deep. But your love, Yuri, was never still, yet very deep. Troubled waters was when you shined and made love manifest. Such love is always in the eyes of the stars.

We will never forget WA 6-7412. Look out comrades out there in the universe! Here she comes!!! What a show. And to the Kochiyama family, lest we forget, love goes on forever because it is born in a part of us that cannot die. I love you all and thank you for being Yuri’s rock and inspiration.

Love you always.

Stiff resistance,

Your brother,

Dr. Mutulu Shakur.

P.S.

For all the P.O.W.’S, P.P.’S, exiles and martyrs.

Dr. Mutulu Shakur is a Black nationalist political prisoner and acupuncturist. He is currently incarcerated in the U.S. Penitentiary, Victorville, in Adelanto, CA.

1 week ago

Yuri the Riveter

A few years ago when I was first becoming politicized and scoping for the imprints of past leaders, there appeared Yuri. Of course it was by way of that famous black-and-white photo of young Yuri, speaking at an anti-war demonstration, and looking astoundingly fierce. Yuri resembled the worn photos I have of my own mother when she was in her mid 20s, and past my age only by a few years. What I felt when I saw this photo is how I imagine others felt when they saw Rosie the Riveter. To me, this photo was and is bravery and badassery personified.

While this image and Yuri’s lifelong resistance alongside Japanese American, Puerto Rican, and Black people urged me to practice outward acts of bravery of my own, learning about Yuri’s later life as a mother inspired me in a different way. In an interview, Yuri’s daughter recalled that their house “felt like it was a movement 24/7.” I imagined a home regularly warmed from stoves and body heat, with the lively din of chatter and laughter, and talk of the political and the everyday seamlessly intermixed.

Through her lifetime commitment of activism in myriad ways, Yuri taught me that activism isn’t confined to meeting rooms, or even on occupied streets. Yuri taught me that community work extends beyond tactics and strategy but is deeply interpersonal: it is how you treat youth and elders, how you relate to your neighbors, and with whom you choose to share your life, in love and in struggle. Yuri taught me that activism isn’t always bullhorns and storming the streets, it is humility, generosity, and fervent, unyielding compassion.

Minh Nguyen is an exhibit developer for the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle’s International District.

1 week ago

I met Yuri on the pilgrimage to Tule Lake internment camp immediately following the 9-11 attacks in NYC. The rise in overt racism against anyone who appeared to be Arab or Muslim made the pilgrimage especially powerful—it seemed as if history was on the verge of repeating. Tule Lake was the camp where Japanese American dissenters (“no-no boys”) were sent, and the dissent continued from inside, leading to the construction of a jail inside the camp. I sometimes accompanied Yuri as she used her wheelchair to visit different parts of the camp’s ruins, and she was always very kind, but also very fierce in her political commitments and support of young people taking up the fight for true freedom and justice. She was the first Asian American activist elder I met in the Bay Area, and thanks to her, I feel connected to an important lineage, one that continues to inspire me today—a touchstone I come back to often. I will always be grateful.

Kenji C. Liu is a poet, educator, and cultural worker.

1 week ago

Yuri showed me what it meant to be an Asian American radical when she came to my college campus back in the day when the Asian American movement was embryonic. The Kochiyamas welcomed young activists like me into their Harlem apartment and they were always warm, generous and gracious. She has embodied what it means to live for social justice and I will always keep her spirit and shining example close to my heart.

Helen Zia is a writer & activist.

1 week ago

Not Ashamed to Die

Yuri was one of my New York O-nesans - “New York” meaning bad ass in 1970s SoCal-ese and “o-nesan” meaning beloved and respected older sister in Japanese. Along with Michi Weglyn, Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig and Kazu Iijima, these four Nisei women were unlike any I - and most West Coast Sansei - had ever known before and each of them in singular and collective ways became political, professional and personal Big Sisters not only to me but to my entire generation.

Michi was the elegant costume designer turned hardcore history detective whose book, Years of Infamy was the first historical investigation of the WWII incarceration written by one of its inmates. Aiko is the researcher who found smoking gun evidence that the U.S. government premeditatively suppressed, altered and destroyed critical documents regarding the mass incarceration. Kazu was, according to Yuri, “the most informative and compelling Asian American woman on the East Coast” and the one Yuri credits for bringing her into the Asian American movement. All of these extraordinary women, as it turns out, were blessed with exceptional husbands - Walter Weglyn, Jack Herzig, Tak Iijima and Bill Kochiyama - each of them also very special to me. In their exhaustive support of their wives, they were truly the men behind the women, enabling Michi, Aiko, Kazu and Yuri to do what they did, making this world a better place for generations to come.

I would venture that the majority of accolades and remembrances of Yuri will be on her vast political contributions as Asian Pacific America’s foremost heroine. As much as I look forward to reading them - and encourage everyone to put down their own memories and tributes - for once I may be among the one percent, of those remember Yuri, not as much for her political contributions as being a mere mortal who succeeded in living well - and a corny Nisei lady at that.

Christmas Cheer was one hella production considering it was produced pre-technology-as-we-know-it and must have taken months to write and assemble since it was really a national newspaper in disguise with a circulation of hundreds of people. (In response to my email, Jimmy joked that Yuri and Bill must have had six kids in order to handle the production demands.) Each issue listed every marriage and baby born during that year from NY to Hawai’i as well as articles written by each of the kids. Many of the early issues had themes that were carried out in the design and writing. For example, the theme of the 1959 issue was popular magazines with column titles such as “Children’s Digest” for the kid’s articles, “Parents” for the baby column, and “Modern Romances” for the weddings - with each headline lettered in their corresponding magazine’s logo.

They reveal how wonderfully downhome and downright corny Yuri and Bill were. Or rather, korny. They had a penchant for substituting “k’s” for “c’s” - kind of like we did later with Amerika but in 1951 it was phrases like “Kochiyama Klan Kapers to Kinfolk in Kalifnorniya.” When my daughter Thai Binh was little, she used to say how corny adults are. Well, this was pure corn. We are much too cool to be corny, which is really too bad.

Most notably, Yuri and Bill’s connection to all of humanity is apparent through the issues from the first to the last. Mostly, of course, it was everyday family and folks they cherished and reported on as if they celebrities. Each issue listed some hundred people they saw, corresponded with or just plain thought of through the year. And sometimes they mingled with for-real celebrities who I’m sure they treated like everyday folk. Besides the famous visit from Malcolm X in 1964, the 1958 issue reports that they met First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Little Rock NAACP leader Daisy Bates and renowned Zen Buddhist scholar D.T. Suzuki. I’m sure this trio never appeared in the same article together again. As so many have testified to Yuri’s radical politics and passion for justice, and so many of us remember Bill’s quiet strength and resolve, these Christmas Cheers are testimony to their deep and oceanic love of ordinary life and just plain folk.

One caveat: as much as Yuri was salt-of-the-earth, she was also star-struck - for example, running after Japanese actress Miyoshi Umeki for her autograph with three kids on each side of her holding on for dear life. And yet this is precisely what made Yuri the extraordinary person she was: her capability to be a political powerhouse as well as a corny Nisei lady. She treated every student and admirer in the same manner she treated the biggest and baddest revolutionary - perhaps because she was herself a unity of what others might think of as contradictory. By her words and deeds, she dared us to struggle. But by her example, she also tells us to have a life - have children, run after autographs, be corny, savor everything.

Horace Mann once said, “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” Yuri was not ashamed to die. As much as this is a tribute to Yuri, I’d like to end with a note of acknowledgement and thanks to Yuri’s surviving children Audee, Eddie, Jimmy and Tommy for sharing their mother with too many people for all these many years. Especially when they were young and came home to find their home a youth hostel or Grand Central Station. And especially now when what would ordinarily be a private grieving must be extraordinarily shared with thousands.

Karen Ishizuka’s latest book is on the making of Asian America to be published by Verso Press in 2015.

Directed, produced, photographed, recorded & edited by C. A. Griffith & H. L. T. Quan, along with Co-editor Paul Hill, this documentary was completed through a prestigious, Art & Technology post-production residency award at Wexner Center for the Arts (2009-2010). Mountains that Take Wing is distributed by Women Make Movies and available for you to buy or rent.

Participant Biographies

A

Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Angela

Y. Davis is an internationally acclaimed scholar, professor, author and

activist. Her parents were teachers and activists, and as a child

growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, she witnessed and experienced the

brutality of the Jim Crow regime of intolerance, violence and hatred. In

1969, she was fired from her Assistant Professor position in UCLA’s

Philosophy Department because of her politics and membership in the

Communist Party, but was rehired after public protest. A year later, her

involvement in the campaign to free the Soledad Brothers lead to a

warrant for her arrest and placement on the FBI’s Most Wanted List. Once

captured, international campaigns to “Free Angela Davis” lead to her

eventual release and acquittal on all charges. Davis remains a staunch

advocate for prison abolition and has developed powerful critiques of

the criminal justice system. Her books include If They Come in the

Morning, Angela Davis: An Autobiography, Women, Race and Class, Women

Culture and Politics, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, Are Prisons

Obsolete?, Abolition Democracy, and Beyond the Frame: Women of Color and

Visual Representation.

Born in 1921, Yuri Kochiyama is a dedicated grassroots organizer, activist and an archivist of the Civil Rights Era. Nominated for a 2005 Nobel Peace Prize, among grassroots communities she is best known for her political involvement with Malcolm X, the Puerto Rican Independence Movement, the Asian American Movement and campaigns to release U.S. political prisoners. After her experience witnessing her father’s abduction by the FBI and her family’s interment during World War II, Kochiyama was primed for activism. In 1960, when she and her husband moved with their large family into public housing in New York’s Harlem, she worked with neighborhood educational struggles and rapidly became a respected community activist and organizer. She met Malcolm X at a courthouse after she’d been arrested in a labor protest. She joined his Organization of Afro-American Unity and supported a Pan-Asian perspective by collaborating with the Hibakusha (Japanese Atom Bomb survivors) and having a strong stance against the Vietnam War. Despite her frail health, Kochiyama remains undaunted in her efforts to free U.S. political prisoners; her personal correspondence has sustained hundreds of men and women both behind the wall and once they gained freedom. Kochiyama devotes her life to progressive causes and is an inspiration to young people and activists around the globe.

The subject of several documentaries and books, Kochiyama moved to Oakland in 1999. She and Davis live several miles apart and cross paths regularly at conferences and political events. Her book, Passing It On-A Memoir, was published in 2004. The reviews include one by Angela Davis: “In this book, [Kochiyama] passes on a legacy of humility and resolve, vitality and resistance, and, perhaps most important of all, hope for the future.”

The Conversations

Yuri Kochiyama and Angela Y. Davis embody personal and political experiences, theories, struggles and art. They are writers, friends, spiritual leaders, aunts, mothers, lovers, educators, warriors, icons, and role models who inspire and challenge the larger and often hostile society, their own generations, and many generations to come. Together, they constitute a culture of social justice and human rights.

With a combined history of nearly a century of community activism, Angela and Yuri shared time in 1996 to discuss their lives and their passion for justice. Although their paths had crossed many times, this was the first occasion they had an in depth conversation with one another. Their dialogue is full of vitality, humility, resolve, hope.and great love. What they have to say about the ethical and social implications of war and the vast prison industrial complex on education, civil liberties and the arts proves to be especially perceptive and poignant when they pick up their conversation twelve years later in 2008. MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING is a compilation of the conversations between these two amazing women on life, struggles and liberation. Davis’s and Kochiyama’s, vast historical knowledge, cogent observations and analyses are passionate and compelling, while offering important lessons in empowerment and community building for current and future generations.

The fervent and diverse styles of teaching and leadership of generations of women inspire the conversational format of MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING. The film honors the breadth and depth of knowledge achieved through the recursive nature of conversation – where complex, challenging subjects and often painful memories and histories are brought to light, and then later, a more nuanced and multifaceted understanding is gleaned from the time and additional context provided. The conversational format was also inspired by Co-Director C. A. Griffith’s experiences while filming Eyes on the Prize, where she observed that many natural, relaxed and fascinating exchanges often happened when shooting paused for film or sound reel changes. Griffith and Co-Director, H. L. T. Quan wondered what gems might arise if they had an opportunity to capture what Davis and Kochiyama had to say to each other. MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING -ANGELA DAVIS & YURI KOCHIYAMA offers audiences the gift of these remarkable women’s lives and their conversations about life, individual and community strategies to resist oppression, and their steadfast resolve that a more just and humane world is not only possible, but vital.

C. A. Griffith and H. L. T. Quan struggled for over a decade to complete this film. Thanks in large part to invitations to screen early cuts of the film and receipt of extensive audience feedback at the University of California Irvine and Riverside, along with the in-kind post-production award from the Wexner Center for the Arts, they were able to complete the documentary in late summer 2009. MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING was filmed in HD, MiniDV and Hi8 video. Originally planned as a series of conversations between Davis and three generations of women doing cultural work – June Jordan, Elizabeth Martinez, Julie Dash, Jude Narita, Abbey Lincoln, The Poetess, among others – the original project scope was too expansive for one film and was refocused on political culture, Davis and Kochiyama.

http://www.racialicious.com/2014/06/02/ahead-of-her-time-yuri-kochiyama-1921-2014/

‘AHEAD OF HER TIME’: YURI KOCHIYAMA (1921-2014)

By Arturo R. García

As the East Bay Express reported in 2002, Yuri met Malcolm X that October while she was being arraigned at a Brooklyn courthouse, taking the opportunity to shake his hand — but also to challenge him.

“I admire what you’re doing,” she told him. “But I disagree with some of your thoughts.”

“And what don’t you agree with?” Malcolm replied.

“Your harsh stand on integration,” she said.

But rather than sour their acquaintance, the encounter served as the starting point to a friendship that blossomed after Malcolm left the Nation of Islam and formed the Organization for Afro-American Unity, which she joined:

That year, she invited him to her apartment to meet some hibakusha, atom-bomb victims who were traveling on the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Mission. They wanted to meet Malcolm X more than anyone else in America. She doubted that he would come, but as the program began, a knock came at the door. There stood Malcolm, with one of his bodyguards.

Yuri remembers his words from that evening well. He told the hibakusha he could see their scars, and that Harlem bore scars too, the result of racism. He talked of the European colonization of Asia, a miserable history it shared with black nations. “And I remember he said the struggle of the people of Vietnam is the struggle of the Third World, a struggle against imperialism,” Yuri recalled in her room the other day, still impressed.

Malcolm opened Yuri’s eyes to the depth of American racism, her daughter Audee said. “At a certain point, she believed not just in civil rights, but felt it was a lot deeper than civil rights and that we had to look at US policy in this country and across the world,” Audee said. His refusal to sell out, as well as his willingness to change, earned her respect. “He symbolized an uncompromised challenge to policy and the social structure,” explained Greg Morozumi, a Kochiyama family friend who helps run the Eastside Arts Alliance in Oakland. “He was going for self-determination of black people and refused to sell out at any point.”

When Malcolm traveled to Africa, he sent the Kochiyamas eleven postcards from nine different countries. “Still trying to travel and broaden my scope, since I’ve learned what a mess can be made by narrow-minded people,” he wrote in one. “Bro. Malcolm X.”

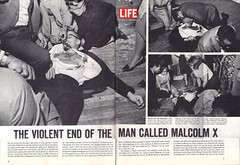

Kochiyama holds Malcolm X after his fatal shooting in February 1965. Image via Discover Nikkei.

Both Yuri and her husband were present at the Audubon Ballroom on Feb. 21, 1965, when Malcolm was shot and killed during a speech. Life Magazine captured not just his death, but Yuri being at his side during his final moments.

“I said, ‘Please, Malcolm, please, Malcolm, stay alive,’” she told Democracy Now in 2007. “But he was hit so many times. Then a lot of people came on stage. They tore his shirt so they could see how many times he was hit. People said it was like about thirteen times. I mean, the most visible is the one here on his chin. He was hit somewhere else in the face, and then he was just peppered all over on his chest.”

But as her granddaughter recounted, Kochiyama continued her work after Malcolm’s death, joining not only the Republic of New Africa, but the Puerto Rican Young Lords Party and Asian Americans for Action — building “bridges, not walls,” as she would later put it, becoming an inspiration to generations worth of activists.

“Today seems a little darker without Yuri’s light in the world,” Jenn at Reappropriate wrote on Sunday. “But I think Yuri would be the first to want us to mourn her passing by rededicating ourselves to the fight; by finding our missions; by learning from each other; and by vowing to never let our battle cries fall silent.”

Post navigationhttp://www.racialicious.com/tag/yuri-kochiyama/

http://modelminority.com/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=431:an-activist-life-15-minutes-with-yuri-kochiyama-&catid=43:leaders&Itemid=56

Knowledge, Generosity, and Yuri Kochiyama

Submitted by Sean Miura on June 2, 2014

"Don't become too narrow. Live fully. Meet all kinds of people. You'll learn something from everyone."

It is with a heavy heart and a reflective spirit that our community remembers and meditates on the life of Yuri Kochiyama. For over half a century, she has helped shape and redefine conversations around race, gender, and justice. It is Yuri's active and generous practice -- sharing knowledge and building deep solidarity -- that has tied so many of us to her legacy.

"Don't become too narrow. Live fully. Meet all kinds of people. You'll learn something from everyone." -- Yuri Kochiyama

I first stepped into Sumi Pendakur’s office eight years ago. Sumi was assistant director of Asian Pacific American Student Services at the University of Southern California at the time, and made herself available to students across campus. I came to USC believing that I knew everything there was to know. When angry, I expected everyone to be as angry as I was. When ready for action, I expected an army by my side. I would come to Sumi time and time again, hoping for affirmation. Perhaps a fellow student was not radical enough for me. Perhaps I felt an organization was not following their mission the way I expected. Perhaps I was feeling unheard in class and outraged at the politics of my professors. Time and time again Sumi would listen -- and then she would ask questions. She would help me analyze the situation, ask me to consider angles I didn’t even know existed, and in the end I would leave her office understanding that, perhaps, I did not know everything there was to know.

These moments of grounded reflection have shaped my process and growth as a community organizer. We often grow thanks to the generosity of those around us, and those whose work we read and follow. We take this inherited knowledge, study it, adjust our perspective, and then pass it forward. It is through this process of learning and sharing that our understanding of the world changes, and it is this very process that has connected so many of us to Yuri Kochiyama.

I did not know Yuri, nor do I know as much of her work as I should. Her spirit, like mist over permafrost, has floated through our conversation and community spaces, evaporating into our actions and words. Yuri opened her home to visitors in New York and held countless meetings at her apartment, introducing attendees to lifelong collaborators and seeding projects innumerable. She modeled tangible solidarity, contributing her hands, her feet, and her voice to Black Panthers and the Young Lords (among many other organizations). Her image amongst “Free Mumia” signs, energy radiating from her powerful face, will not soon be forgotten; how could it be? We have known her words, even if we did not know her, and we have known her actions, even if we did not have the privilege to personally build with her.

It is with great generosity that Yuri shared her life and her stories, raising scores of organizers, activists, thinkers, and writers. Today this indomitable spirit still burns in her work, her mentees, and her family -- who continue in the revolutionary resistance she embodied. We will still fight for freedom in our government and society, in the way Yuri fought to achieve a more just and free-thinking world.

With each generation the conversation changes, but the spirit of these mentors, thinkers, and elders persists. There is so much more learning, so much more sharing to be done.

Our thoughts are with the Kochiyama family, Yuri’s close community, and those who carry her legacy ever forward.

Rest, rise, and revolutionize in power.

***

You can read more about Yuri Kochiyama's life and legacy here. Please add your memories and reflections in the comments below.

The author would like to thank the many people who helped shape this piece in various ways, particularly Cynthia Brothers, Terry Park, Juliet Shen, Trung Nguyen, Lorraine Bannai, and Tracy Nguyen-Chung.

Accompanying photo by An Rong Xu, a documentary photographer based in New York.

Rest in Power, Yuri Kochiyama: A Civil Rights Hero Who Inspired a Generation

June 1, 2014

Reappropriate

In her own words, from Legacy to Liberation:

What I would say to students or young people today. I just want to give a quote by Frantz Fanon. And the quote is “Each generation must, out of its relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it or betray it.”

And I think today part of the missions would be to fight against racism and polarization, learn from each others’ struggle, but also understand national liberation struggles — that ethnic groups need their own space and they need their own leaders. They need their own privacy. But there are enough issues that we could all work together on. And certainly support for political prisoners is one of them. We could all fight together and we must not forget our battle cry is that “They fought for us. Now we must fight for them!”

Yuri Kochiyama was my hero. Yesterday, I wrote about the 12 year anniversary of Reappropriate; this blog would not have been built had I not been inspired as a student by Yuri Kochiyama’s life of activism, and the work of other civil rights legends in her generation.

Today seems a little darker without Yuri’s light in the world. But I think Yuri would be the first to want us to mourn her passing by rededicating ourselves to the fight; by finding our missions; by learning from each other; and by vowing to never let our battle cries fall silent.

Thank you for your life, and the legacy you left for us, Yuri Kochiyama. Rest in power.

Read More:

Fascinasians: Rest in Power, Yuri Kochiyama

Discover Nikkei: A Heart Without Boundaries, a paper by grand-daughter Maya Kochiyama written in 2011

18MillionRising

NPR CodeSwitch

The Nerds of Color: R.I.P. Yuri Kochiyama: For All The Free by Jeff Castro

Time Magazine

The Progressive Pulse

Grace Hwang Lynch at BlogHer: Remembering Yuri Kochiyama, Civil Rights Activist

Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Los Angeles: Yuri Kochiyama, Hero of Civil Rights and Racial Justice, Passes Away

BecauseOfYuri Tumblr

ChangeLab’s Storify of Yuri tweets

Hyphen Magazine: Knowledge, Generosity, and Yuri Kochiyama

Angry Asian Man: Legendary activist Yuri Kochiyama dies at 93

LA Times

Yuri Kochiyama©

Photo collage with Fuji Crystal Archive prints, 1997

Size: 24" x 27"

Artist: Masumi Hayashi

Japanese American Internee Portraits

Yuri Kochiyama: Remembering a Japanese-American Leader and Social Activist

by Patricia Yollin

June 6, 2014

In Memory of Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014)

Dear Alumni and Friends,

We received word of the passing of Yuri Kochiyama who touched and inspired the lives of thousands of people through her decades-long activism and incredible dedication to social justice.

The Kochiyama Family has issued a brief statement:

"Life-long activist Yuri Kochiyama passed away peacefully in her sleep in Berkeley, California on the morning of Sunday, June 1 at the age of 93. Over a span of more than 50 years, Yuri worked tirelessly for social and political change through her activism in support of social justice and civil and human rights movements. Yuri was born on May 19, 1921 in San Pedro, California and spent two years in a concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas during World War II. After the war, she moved to New York City and married Bill Kochiyama, a decorated veteran of the all-Japanese American 442nd combat unit of the U.S. Army.

Born in 1921, Yuri Kochiyama is a dedicated grassroots organizer, activist and an archivist of the Civil Rights Era. Nominated for a 2005 Nobel Peace Prize, among grassroots communities she is best known for her political involvement with Malcolm X, the Puerto Rican Independence Movement, the Asian American Movement and campaigns to release U.S. political prisoners. After her experience witnessing her father’s abduction by the FBI and her family’s interment during World War II, Kochiyama was primed for activism. In 1960, when she and her husband moved with their large family into public housing in New York’s Harlem, she worked with neighborhood educational struggles and rapidly became a respected community activist and organizer. She met Malcolm X at a courthouse after she’d been arrested in a labor protest. She joined his Organization of Afro-American Unity and supported a Pan-Asian perspective by collaborating with the Hibakusha (Japanese Atom Bomb survivors) and having a strong stance against the Vietnam War. Despite her frail health, Kochiyama remains undaunted in her efforts to free U.S. political prisoners; her personal correspondence has sustained hundreds of men and women both behind the wall and once they gained freedom. Kochiyama devotes her life to progressive causes and is an inspiration to young people and activists around the globe.

The subject of several documentaries and books, Kochiyama moved to Oakland in 1999. She and Davis live several miles apart and cross paths regularly at conferences and political events. Her book, Passing It On-A Memoir, was published in 2004. The reviews include one by Angela Davis: “In this book, [Kochiyama] passes on a legacy of humility and resolve, vitality and resistance, and, perhaps most important of all, hope for the future.”

The Conversations

Yuri Kochiyama and Angela Y. Davis embody personal and political experiences, theories, struggles and art. They are writers, friends, spiritual leaders, aunts, mothers, lovers, educators, warriors, icons, and role models who inspire and challenge the larger and often hostile society, their own generations, and many generations to come. Together, they constitute a culture of social justice and human rights.

With a combined history of nearly a century of community activism, Angela and Yuri shared time in 1996 to discuss their lives and their passion for justice. Although their paths had crossed many times, this was the first occasion they had an in depth conversation with one another. Their dialogue is full of vitality, humility, resolve, hope.and great love. What they have to say about the ethical and social implications of war and the vast prison industrial complex on education, civil liberties and the arts proves to be especially perceptive and poignant when they pick up their conversation twelve years later in 2008. MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING is a compilation of the conversations between these two amazing women on life, struggles and liberation. Davis’s and Kochiyama’s, vast historical knowledge, cogent observations and analyses are passionate and compelling, while offering important lessons in empowerment and community building for current and future generations.

The fervent and diverse styles of teaching and leadership of generations of women inspire the conversational format of MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING. The film honors the breadth and depth of knowledge achieved through the recursive nature of conversation – where complex, challenging subjects and often painful memories and histories are brought to light, and then later, a more nuanced and multifaceted understanding is gleaned from the time and additional context provided. The conversational format was also inspired by Co-Director C. A. Griffith’s experiences while filming Eyes on the Prize, where she observed that many natural, relaxed and fascinating exchanges often happened when shooting paused for film or sound reel changes. Griffith and Co-Director, H. L. T. Quan wondered what gems might arise if they had an opportunity to capture what Davis and Kochiyama had to say to each other. MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING -ANGELA DAVIS & YURI KOCHIYAMA offers audiences the gift of these remarkable women’s lives and their conversations about life, individual and community strategies to resist oppression, and their steadfast resolve that a more just and humane world is not only possible, but vital.

C. A. Griffith and H. L. T. Quan struggled for over a decade to complete this film. Thanks in large part to invitations to screen early cuts of the film and receipt of extensive audience feedback at the University of California Irvine and Riverside, along with the in-kind post-production award from the Wexner Center for the Arts, they were able to complete the documentary in late summer 2009. MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING was filmed in HD, MiniDV and Hi8 video. Originally planned as a series of conversations between Davis and three generations of women doing cultural work – June Jordan, Elizabeth Martinez, Julie Dash, Jude Narita, Abbey Lincoln, The Poetess, among others – the original project scope was too expansive for one film and was refocused on political culture, Davis and Kochiyama.

ASIAN AMERICAN MOVEMENT EZINE

AZINE

Progressive, Radical, and Revolutionary Asian American Perspectives

Home / East Wind Vol. 1 No. 1

Asian Women: Past, Present and Future

apipower - Posted on 13 October 2012

by Yuri Kochiyama

Asian Women: Past, Present and Future

apipower - Posted on 13 October 2012

by Yuri Kochiyama

Yuri

Kochiyama has been a prominent activist in the Asian and Third World

movement for many years. Her involvement in the anti-war movement,

community struggles, redress/reparations, workers organizing and

international liberation support work has earned her the respect of

thousands of people. On March 7, 1981, she delivered this keynote

address to the East Coast Asian Student Union's Asian Women's Conference

held at Mt. Holyoke College.

* * *

Thank you for the opportunity and privilege of being here with you. We as Asian women are here, I think, for several reasons: 1 ) to get to know one another, have dialogue with each other, feel good vibes of mutual concern and unity; 2) to explore who we are, have been and where we would like to go as Asian women, as Third World women, international women and just plain women; 3) to seriously consider questions like: What brought about stereotypes? What has been the history of Asian women? Are we subservient to societal forces, traditions, trends? What should we oppose; what should we support? Where are we now? What are our needs? In a constantly changing world, priorities change as new problems develop. Strategies and tactics must change as assessments become clearer. Minority women's rights and general women's rights must be placed in proper perspective.

We must also realistically realize that the era of visibly recognizable Asian women in the United States may be only for a few more generations. A large percent of Asian women are marrying non-Asians and their heirs may not look that Asian, but a woman's most personal rights are the right to choose one's mate and the right to procreate when she desires or is ready to do so.

Also, the large influx of Asian refugees must be our concern, for the problems they will face in this country should not be shouldered by themselves alone. We, as Asians and as concerned women, must keep abreast of their needs and adjustment.

Thus, my topic will be: "Asian women, past, present and future." Let's begin with our past. Whether our backgrounds take us back to China, Korea, Japan, the Philippines, India, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Hawaii or other Pacific Islands - we all come from a history of feudalism, foreign domination, colonialism, Asian national traditions, Western chauvinism and racism. That's a whole lot of oppression.

All of our mothers knew the meaning of obedience, subservience, and knowing their place in both a male dominated and a racist society. Women's place worldwide, but especially in Asia, was/is second class. A quotation from India reads: "Man is gold. Woman is only an earthen vessel."

We must admit that such inequities are part of our Asian heritage, but it does not have to remain so. We must recognize that all heritage and traditions are not necessarily something to be proud of. We must continually discard what is confining or harmful and create what is beneficial, useful, broadening and humane. But the other side of the coin of the feudal period - and other eras mentioned - was constant struggle against injustices. Women in Asia as well as women in the Third World and everywhere have never ceased in their struggles. Today, that struggle continues even in this so-called democracy where inequities, injustices, exploitation and racism persist. New ideas and lifestyles must improve the quality of life not only for women but for men, children, everyone.

However, there are Asian traditions that we can continue and hold on to: the deep respect for the elderly; the preciousness of children the appreciation of nature; the proximity to the soil (land); and the reverence for the ancestors.

The bamboo has always been the symbol for the Asians - men and women. It's gracefulness and strength - able to bend with the wind; resilient but unbreakable; rooted in the solid ground.

It sounds nice, but today, we cannot deal in simple analogies and symbolism. Women in Asia are coming together, joining hands on problem they consider mutual. One of the struggles that liberated women of Japan are fighting against - along with women of Korea, Taiwan, Philippines, Okinawa and Thailand - the growing sexploitation by Japanese businessmen who travel to those mentioned countries. The problem is so serious that progressive Asian leaders have publicly condemned Japanese prostitution tourism which has been booming in the 1970's. One Pilipino leader stated that this perpetration of a social evil is like a "sexual invasion of Imperial soldiers wearing civilian clothes." This immoral indulgence has expanded to Sri Lanka and Nepal.

Prostitution tourism is a classic example of the distorted political/economic relationship between capitalism and exploitation of women; and the social aspect of the violations of human rights meaning women's rights and women's dignity.

We are now in the 1980's. As Asian American women we have graduated from identity crisis to community organizing to Third World interaction to study groups, political education to supporting international liberation struggles. Much water has gone under the bridge. Asian awareness was born during the fight for Ethnic Studies twelve years ago and flowered during the Viet Nam War when we proudly marched in Asian contingents on both the West and East Coast in support of our Asian sisters and brothers in Viet Nam, Laos and Cambodia.

In 1971, two historic meetings took place in Canada, one in Vancouver, the other in Toronto ... the Indochinese Women's Conference where several dozen Asian women along with several hundred Third World and white women from North America met with six unforgettable, indomitable women from Indochina; revolutionary women whose courage, spirit and warmth all struck the North Americans with a humanity and humility. Perhaps, these women - who were teachers, doctors, housewives, mothers, workers, all who worked collectively in the struggle (one who spent six years in the Tiger cages and survived) - brought with them the profoundest meaning or the best of Asian womanhood. It was a combination of gentility with strength, zeal with patience, commitment with understanding.

For most North American women who attended, it was the most moving event of that time. It was an international, transcontinental exchange during the height of the war, when North American women learned about the horrors and heroics that a cruel, unrelenting war could evoke; and Southeast Asian women heard for the first time the history of the Black, Native American, Chicano, Puerto Rican and Asian experience in America. What an impact these women must have made on one another.

Unforgettable, too, was that the planning for the conference had to be done clandestinely for fear that the U.S. government would stop the women from attending this momentous event.

We are here today at another women's conference. We did not cross oceans to gather. We do not need translators. There is nothing clandestine about this gathering. It is not an international meeting. But, this conference of East Coast Asian women can be meaningful, educational and have its own kind of impact. We are living in a very serious period of national retrogression with domestic policies, budget cuts and media control already closing avenues of special social, cultural outlets such as this. It is to your credit that this conference got off the ground, and that Asian women made an effort to attend. A couple of years from now, there may not be any more Asian or Third World gatherings. Asian Studies itself is being iced out across the country along with other ethnic studies. In New York, only City College and Hunter College have a few courses. In event that these meetings are halted, we must think of some kind of communication links in the future.

The Bakke and Weber cases made mileages for U.S. domestic policies against affirmative action, not only in education but in work places. We must fight to keep the gains made in the '60s.

Ethnic ties, ethnic unity and ethnic organizing have to give rise to ethnic creativity and talent. We Asians can be proud of the number of Asian women artists, writers, poets, singers, dancers, musicians, photographers, film makers. Women like - Nobuko Miyamoto, Chris Choy, Fay Chiang, Roberta Uno, Camillia Ry Wong, Diane Mark, Ginger Chih, Mitsu Yashima, Nelly Wong, Kazu lijima, Nancy Hom, Renee Tajima, Hisaye Desoto, Janice Mirikitani, Grace Lee Boggs and others. Art is not for art's sake.-For people's artists, art is for people's sake.

Internationally, we live in a world where all peoples and nations are interdependent. The oppression of any nation or people must be the concern of all. Today, as we see struggles enflaming in El Salvador, Namibia, the Middle East, Philippines, Eritrea, East Timor, Afghanistan - such diverse places - what strange names - now areas we must keep our eyes on. We must read and understand what is happening there in terms of U.S. involvement and imperialism and give support to those in liberation struggles. We are Third World women, international women.