THE MUSICAL LEGACY OF AMIRI BARAKA: The Modern Jazz Critic As Cultural Historian, Creative Artist, Social Theorist, And Philosophical Visionary

[This essay is dedicated to the memory and eternal presence of Amiri Baraka/Leroi Jones (1934-2014) who was not only a great artist, mentor, friend, colleague, and comrade but also--like he was for so many others around the world--a towering influence on my art and life]

“ ... Negro music is essentially the expression of an attitude, or a collection of attitudes, about the world, and only secondarily an attitude about the way music is made...Usually the critic's commitment was first to his appreciation of the music rather than to his understanding of the attitude that produced it. This difference meant that the potential critic of Jazz had only to appreciate the music, or what he thought was the music, and that he did not need to understand or even be concerned with the attitudes which produced it...The major flaw in this approach to Negro music is that it strips the music too ingenuously of its social and cultural intent. It seeks to define Jazz as an art (or a folk art) that has come out of no intelligent body of socio-cultural philosophy…”

--Leroi Jones, "Jazz and the White Critic," Downbeat magazine, 1963; later reprinted in his book of critical essays and reviews Black Music (William Morrow, 1968)

“Jazz and the White Critic” was a challenge to jazz writers of all backgrounds to reckon with the lived experience of black Americans and to consider how this experience had been embedded in the notes, tones, and rhythms of the music.”

--John Gennari, Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and its Critics (University of Chicago Press, 2006)

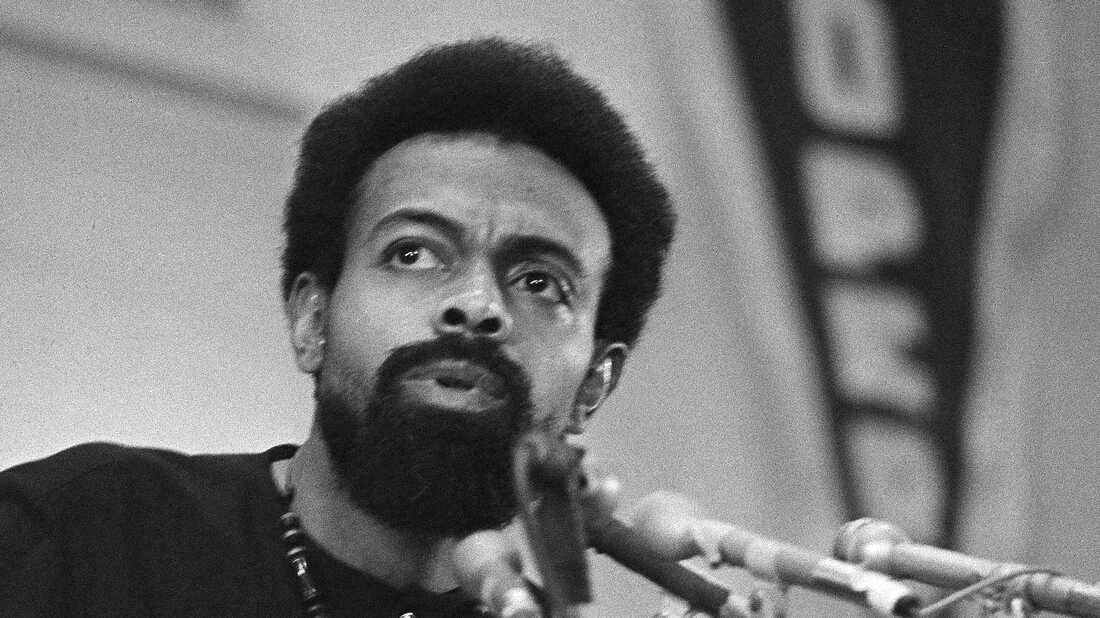

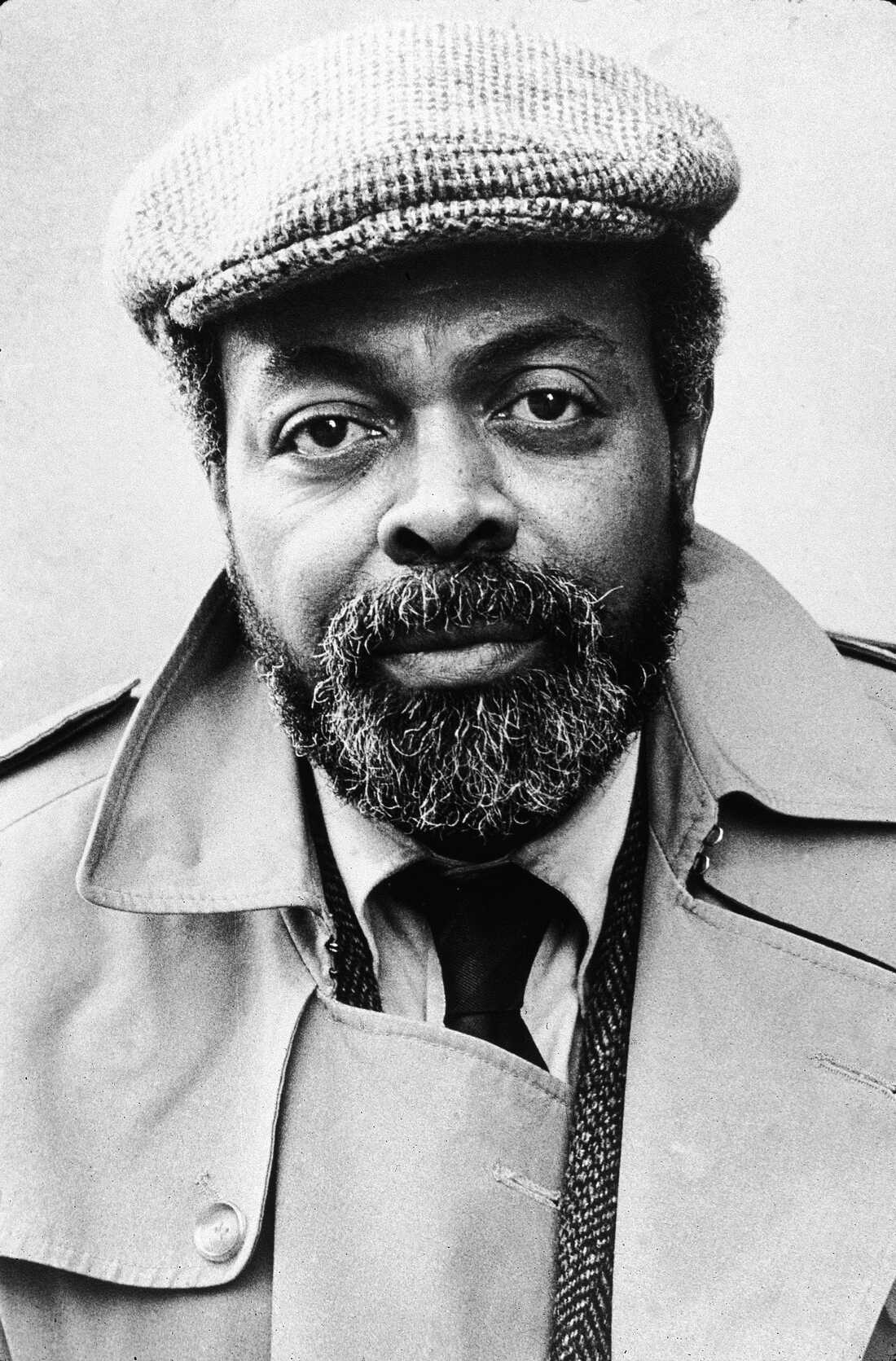

In the name of sheer historical accuracy and perhaps even ultimately a triumphant kind of poetic justice the following emphatic statement bears repeating as often as possible: For fifty years from 1963-2013 Amiri Baraka (also known as Leroi Jones) wrote and published the most profound, influential, and strikingly original body of musical criticism in the United States, as well as some of the most significant--and enduring--cultural and social criticism generally that this country has produced since 1945. This is especially true of his stunning and groundbreaking work in the musical genre of 'Modern Jazz' and his extensive, dynamic, and typically incisive examination of the music's rapid evolution since 1900 in both its visionary "avant garde" modes as well as its more traditional vernacular styles and expressions.

An essential aspect of Baraka’s critical writing on jazz however is also rooted in a deep consciousness and visceral understanding and love of the rural and urban blues/rhythm and blues traditions not only in formal and aesthetic terms but as a complex and historically cumulative social and cultural statement about the ongoing meaning(s) of the content of these musics in both their structural and lyrical dimensions. Thus an appreciation and respect for the ideological complexities and contexts of African American culture as an important economic, social, and political reality as well as an essentially protean artistic force is integral to fully engaging and grasping what Baraka is primarily focused on and concerned with in his writing about the music.

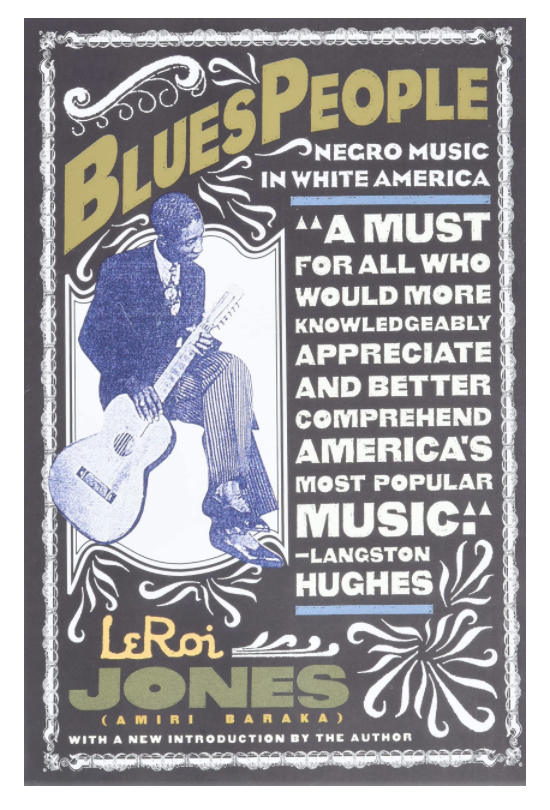

Thus it is not surprising that Baraka's first book about the music, originally entitled Blues People: Negro Music in White America became a seminal, widely acclaimed, and subsequently never out of print historical text. Published by the then 28-year-old writer in 1963, the book was also importantly subtitled in at least a few of its other many editions as "The Negro Experience in White America and the Music That Developed From It." Disdained and even dismissed in some quarters by some haughty and self-important highbrow critics, both white and black, as being too steeped in what they perceived as a fundamentally reductive sociological emphasis in Baraka's analysis of the blues as art and history (a highly inaccurate and quite dubious line of argument echoed in a particularly patronizing and intellectually self serving manner by the celebrated African American novelist and cultural critic Ralph Ellison) Blues People clearly marked a major new turning point in not only the history of Jazz and blues criticism in the United States but in its perception and intellectual appreciation and understanding by music critics generally. Not surprisingly this new consciousness was also beginning to be reflected to some degree in its public reception by audiences.

Despite its ill-informed detractors Blues People also firmly established Baraka as a major intellectual and literary force to be reckoned with because he was not afraid of expressing a strong and independently assertive viewpoint alongside a persistently sharp critical analysis of what the music has meant to black Americans from the standpoint of not only individual citizens or artists but of the mass culture generally. He insisted on an interpretive POV that saw class relations as well as "race" in terms that established a clear hierarchy and division of attitudes and values that informed one's deep affinity for or relative indifference to the various forms and expressions of the blues as creative/stylistic form and artistic identity as well as a distinct and thus substantive and independent sensibility in the larger society as a whole. Consequently Baraka declared that the purveyors of the blues sensibility and its primary cultural progenitors were not only the artists and the intellectual connoisseurs of the form (i.e. critics, academicians, and scholars) but the so-called 'ordinary citizens' who loved and represented and embodied the art themselves (the actual "Blues People" of the book's title). Therein, Baraka insisted, lay the music's true power and ultimate potential as both a creative and social/philosophical force.

In that light it is important to consider that as the great poet Langston Hughes and many other critics and commentators pointed out when the book made its initial appearance that Blues People was in many ways the intellectual and critical culmination of a contentious historical debate raging then (and even to a great extent today) within Black America as well as the larger society over the cultural and thus political and ideological value and meaning(s) of the African American experience and the role of its various artistic forms and artists who through their creative work publicly represent and embody this cultural history. In Baraka's analysis the music serves as both a crucial narrative record (literally as well as on vinyl) of what black people have experienced and an ongoing emotional and psychological register of the impact and effects this experience has had on them and their larger spiritual, existential, and philosophical conception of themselves. As he puts it in his original introduction to the book in 1963:

"In other words I am saying that if the Negro in America, in all its permutations, is subjected to a socio-anthropological as well as musical scrutiny, something about the essential nature of the Negro's existence in this country ought to be revealed, as well as something about the essential nature of this country, i.e. society as a whole...And the point I want to make most evident here is that I cite the beginning of blues as one beginning of American Negroes. Or, let me say, the reaction and subsequent relation of the Negro's experience in this country in his English is one beginning of the Negro's conscious appearance on the American scene...When America became important enough to the African to be passed on, in those formal renditions, to the young, those renditions were in some kind of Afro-American language..."

Baraka also was deeply concerned with how and why these specific musical traditions, techniques, and innovations took the various forms and stylistic identities that they did from the dialectical standpoint of their creators' dynamic, and critically informed engagement with their aesthetic material. One of Baraka's major strengths as a critic is his emphasis always on the process of the creative act in the course of expressing ideas and emotions via the integral elements of music making. This is a major even central aspect of Baraka's writing as a music critic that he strongly maintained and greatly enhanced in all future critiques and celebrations of Jazz, blues, and rhythm and blues following the publication of Blues People.

In Black Music (William Morrow, 1968), his second book devoted to the extraordinary social history and cultural identity of this musical art, Baraka lays out what amounts to a very erudite and casually elegant book-length manifesto on the most advanced, radical, and innovative developments in modern Jazz during the culturally and politically tumultuous 1960s. A trenchant and mesmerizing collection of many of the finest theoretical essays, feature articles, and music reviews that he had written for various national magazines and journals from 1959-1967, Baraka not only critically interprets the revolutionary music of this fascinating historical period but discusses its myriad meanings and values from the direct viewpoint of the individual musicians themselves. What results is a series of riveting, complex, and always critically challenging portraits of these musicians as dedicated cultural workers and the often visionary perspectives that these artists embodied and conveyed to their audiences. Baraka especially draws the readers' attention to the largely black working class and sometimes even more economically challenging (i.e. poor) social and cultural milieu that so many of these musicians and their peers and colleagues lived, created, and performed in. In doing so he reminds us that many of the most profound, lasting, and useful modern art expressions in the United States (and elsewhere) are not merely or exclusively the products of the academic “Ivory Tower” and foundation grant institutions nor are they dependent on the often fickle largesse of wealthy patrons. In fact as Baraka amply demonstrates in his analysis the evidence everywhere of the deep desire and demand for aesthetic, economic, and political self determination among this intrepid generation of musicians, composers, and improvisers is one of the major principles animating their work and overall vision. One of many brilliant examples of this analytical focus can be found in Baraka's intricate, detailed, and powerful dissection of the general aesthetics and cultural values of such legendary and even iconic musicians, composers, and improvisors of the post 1945 modern music era as John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, Wayne Shorter, Cecil Taylor, Joe Henderson, Sun Ra, Archie Shepp, Marion Brown, Milford Graves, Don Pullen, Bobby Bradford, and Roy Haynes, among many others who emerged as a self consciously radical, innovative, visionary. and transformative force in the music since the late 1950s.

Dedicated to “John Coltrane, the heaviest spirit” Baraka's Black Music posed a tremendous intellectual and artistic challenge to an entire generation of artists, critics, and cultural/political activists (and I might add is still doing so some two generations and 45 years later!) to begin to seriously address and attempt to resolve many of the major structural and institutional problems and crises facing not only our creative artists in the realms of music, literature, dance, filmmaking, visual and media art, etc. but our larger communities as well. Toward that end the book provides an important ongoing subtextual narrative about the insidious political economy of the music business and its direct and indirect effects on the musicians themselves who not only have to withstand and tragically negotiate the oppressive and exploitive impositions of white supremacy/racism in all its guises but the even more comprehensive venality of corporate capitalism in the studios, clubs, theatres and general commercial venues where the music was being recorded and/or performed for various live audiences during an era when Jazz, despite its growing richness and vitality in a creative sense, especially was suffering greatly economically as a result of its clearly limited reception and appreciation by the larger society. This unfortunately also included the growing commercial interest in and support for pop, rhythm and blues, and rock musics (resulting in the increasing exclusion and marginalization of Jazz and blues) in the national black community.

Finally, the flagship essay of Black Music that opens the volume contains one of the most prescient, eloquent, historically significant, and intellectually honest essays ever written about the “Modern Jazz” dimension of African American music. Entitled "Jazz and the White Critic" the piece had originally appeared in Downbeat the largest national 'mainstream' Jazz magazine in the country in August, 1963 just before the appearance of his first book on the music Blues People later that year. What remains essential about this prophetic essay is its analytical insistence that the philosophical and cultural aspects of African American music like that of all major aesthetic traditions throughout the world is key to acquiring a genuine knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the art. As he states in his concluding paragraph:

“We take for granted the social and cultural milieu and philosophy that produced Mozart. As Western people the socio-cultural thinking of eighteenth-century Europe comes to us as a historical legacy that is a continuous and organic part of the twentieth-century West. The socio-cultural philosophy of the Negro in America (as a continuous historical phenomenon) is no less specific and no less important for any critical speculation about the music that came out of it...this is not a plea for narrow sociological analysis of Jazz, but rather that this music cannot be completely understood (in critical terms) without some attention to the attitudes which produced it. It is the philosophy of Negro music that is most important, and this philosophy is only partially the result of the sociological disposition of Negroes in America. There is, of course, much more to it than that.” (Italics mine)

The Music: Reflections on Jazz and Blues (William Morrow, 1987)

The long awaited arrival of Amiri's third full volume of music criticism in 1987 published some twenty years after Black Music and twenty-five years after Blues People was not only well worth the wait but added still more brilliant wrinkles to his long-term critique of the music, its artists, and the larger social, economic, and political contexts that it existed and persisted in. Both a dynamic synthesis and extension of previous writing about its historical identity as well as an celebratory examination of its contemporary expressions, The Music is divided between a series of poems that center on Jazz and the blues by both Amiri and his wife, Amina Baraka, which takes up a third of the text, an extraordinary political play entitled The Primitive World: An Anti-Nuclear Musical by Amiri that uses both “avant-garde” as well as more traditional Jazz and blues elements, techniques, and styles in an updated and innovative operatic context. Most of the actors in the production are the musicians themselves who both play and sing their parts. Such important and highly accomplished 'avant' Jazz musicians of the post-1970 era as the tenor saxophonist David Murray, drummer and percussionist Steve McCall, violinist Leroy Jenkins, and the pianist/organist Amina Claudine Myers acted and played in this production.

The last third of the book features 26 virtuosic and typically incisive essays, reviews, liner notes, and feature articles by Baraka written for and published by various national magazines, journals, and newspapers in the 1975-1987 period as well as some new and important critical essays written specifically for the book. Covering everyone and everything from Miles Davis (in a masterful 1985 article for the New York Times) to the history of Jazz and other African American musics in Greenwich Village in NYC to a series of briliant book and music reviews of books and recordings about and by such major musicians as Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Woody Shaw, Cecil McBee, Gil Scott-Heron, Chico Freeman, Ricky Ford, and Craig Harris. There are also a scintillating collection of extremely informative, lyrically written, and politically astute theoretical and critical essays like "Where's the Music Going and Why?", "Jazz Writing: Survival in the Eighties", "The Phenomenon of Soul in African American Music". "Masters in Collaboration", "Blues, Poetry, and the New Music" "AfroPop", "The Class Struggle in Music" and "The Great Music Robbery." There is simply not enough space in this piece to do justice to the crackling intellectual firepower and truly impressive depth and scope of Baraka's writing here; suffice it to say for now that he (re)proves all over and once again exactly WHY he is the preeminent American music critic of the past half century by a very wide margin with virtually no real contenders in sight. Long out of print (and criminally never republished in paperback!) one MUST track down this 1987 hardcover classic and read what it says about a massive range of issues and concerns with respect to the music in not only aesthetic and ideological terms but from the equally profound standpoints of literature (and rhetoric), social theory, cultural history, and political analysis and journalism. One will not come away disappointed. If only the academic departments of 'American and African American Studies' (and all other so-called "ethnic", "humanities", and "cultural studies" programs generally) had professors, public intellectuals, and social activists of Baraka's caliber and clarity running them instead of the often pretentious, biased, and myopic fetishists of "language and culture" who too often ride herd in these fields in U.S. colleges and universities today, we would all be much better informed about the actual strength, beauty, and complex reality of the multiracial and multinational society that we all in fact inhabit. As Baraka makes clear in the essay "Blues, Poetry, and the New Music" from what is finally a GREAT book:

"Each generation adds to and is a witness to extended human experience, If it is honest it must say something new. But in a society that glorifies formalism, i.e. form over content, because content rooted in realistic understanding of that society must minimally be critical of it--the legitimately truthfully new is despised. Surfaces are shuffled , dresses are lengthened or shortened, hair is green or blond, but real change is opposed. The law keeps the order and the order is exploitive and oppressive! The new music reinforces the most valuable memories of a people but at the same time creates new forms, new modes of expression, to more precisely reflect contemporary experience!"

Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music (University of California Press, 2009)

After an astonishing forty five years of endlessly writing, teaching, and lecturing about African American music all over the world it was an absolutely thrilling and inspiring surprise to find yet another extraordinary volume of music criticism by Amiri in the 21st century. Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music (University of California Press, 2009) is an epic 411 page text of 84 essays, reviews, liner notes, articles, and precise literary portraits of and about musicians and their art over a fifty year period.. Taking on a huge canvas of critical themes and musical personalities Baraka carries off one can only be described as a penultimate triumph of the art and craft of music criticism at its highest possible level. In a stunning display and critical synthesis that includes an encyclopedic knowledge of the music, a razor sharp attention to the historical nuances of the music and how it it has stylistically evolved and mutated over the years, and finally a thoroughly independent theoretical and critical perspective on the music in aesthetic, historical, and social/cultural terms, Baraka compiled and summed up what constitutes a comprehensive philosophical treatise on Jazz and blues music in U.S.--and by extension the world-- over the past century.

In this quest Digging joyously and fastidiously examines the work, philosophy, craft, and vision of such GIANTS as John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Wayne Shorter, Miles Davis, Nina Simone, David Murray, Art Tatum, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Billie Holiday, Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy, Andrew Cyrille, Barry Harris, James Moody, Jackie McLean, Sarah Vaughan, Stevie Wonder, Roscoe Mitchell, Fred Hopkins, Pharoah Sanders, Charles Tolliver, Odean Pope,John Hicks, Von Freeman, Jimmy Scott, and Reggie Workman (WHEW!). Baraka also writes with great insight, intelligence, and passion about such exciting and important emerging musicians and composers of the past two decades as Vijay Iyer, Rodney Kendrick, Ralph Peterson, Jon Jang, and Ravi Coltrane.

Finally Digging is an intense, wide ranging, and deeply philosophical and scholarly meditation on, and relentless excavation of, the multidimensional aspects of the music's varied diasporic genealogies, and a celebration of its ongoing presence and importance on both a national and global level. Amiri incorporates everything he has learned and experienced in the both the music and his life (and their endless interconnections). This synergy of the personal and aesthetic gives the book an organic unity and focus that shapes and informs the text as the essays strive to fuse an understanding of politics, history, ideology, and art with a larger vision of "what it all means." Confronting this complicated task is handled beautifully in such sage and critical essays as "The 'Blues Aesthetic' and the 'Black Aesthetic: Aesthetics as the Continuing Political History of a Culture ', "Jazz Criticism and Its Effects On the Music", "Black Music As A Force for Social Change", "Bopera Theory", "Jazz and the White Critic: Thirty Years Later" , "Newark's "Coast" and the Hidden Legacy of Urban Culture", "Blues People: Looking Both Ways", "Miles Later" and "Griot/Djali: Poetry, Music, History, Mesage". "Cosby and the Music", and "The American Popular Song: The Great American Song Book" among others. In other words NO ONE has written about American music with a wider, deeper, and more informed LOVE, UNDERSTANDING and KNOWLEDGE than Amiri Baraka/Leroi Jones or what this music means to the artists who create it and the millions of blues people/citizens from all over the world who listen, dance, sing and live their lives to and with it. On this and much much more besides, Amiri has--as always-- the 'last word' (for now) on the subject:

"...So Digging means to present , perhaps arbitrarily, varied paradigms of this essentially Afro-American art. The common predicate, myself, the Digger. One who gets down, with the down, always looking above to see what is going out, and so check Digitaria, as the Dogon say, necessary if you are the fartherest Star, Serious. So this book is a microscope, a telescope, and being Black, a periscope. All to dig what is deeply serious. From a variety of places,,,the intention is to provide some theoretical and observed practice of the historical essence of what is clearly American Classical Music, no matter the various names it, and we, have been called. The sun is what keeps the planet alive, including the Music, like we say, the Soul of which is Black."

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PUBLISHED MUSIC CRITICISM BY AMIRI BARAKA (aka Leroi Jones): 1963-2009:

Blues People: Negro Music in White America. by Leroi Jones. William Morrow, 1963

Black Music. by Leroi Jones. William Morrow and Company, 1968

The Music: Reflections On Jazz and Blues. by Amiri Baraka and Amina Baraka. William Morrow and Company, 1987

Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music. by Amiri Baraka. University of California Press, 2009

Blues People

The original text is divided into twelve chapters, summarized below.

"The Negro as Non-American: Some Backgrounds"

Baraka opens the book by arguing that Africans suffered in America not only because they were slaves, but because American customs were completely foreign to them. He argues that slavery itself was not unnatural or alien to the African people, as slavery had long before existed in the tribes of West Africa. Some forms of West African slavery even resembled the plantation system in America. He then discusses a brief history of slavery, inside and outside the United States. He argues that unlike the slaves of Babylon, Israel, Assyria, Rome, and Greece, American slaves were not even considered human.

Baraka then further addresses his previous assertion that African slaves suffered in the New World because of the alien environment around them. For example, the language and dialect of colonial English had no resemblance to the African dialects. However, the biggest difference that set the African people aside was the difference in skin color. Even if the African slaves were freed, they would always remain apart and be seen as ex-slaves rather than as freed individuals. Colonial America was an alien land in which the African people could not assimilate because of the difference in culture and because they were seen as less than human.

The horrors of slavery can be broken down into the different ways in which violence was done against African people. In this section Baraka contends that one of the reasons the Negro people had, and continue to have, a sorrowful experience in America is the violently different ideologies held by them and their captors. He transitions from highlighting the economic intentions of Western religion and war to pointing out how the very opposite life views of the West African can be construed as primitive because of the high contrast. He addresses the violence done against the cultural attitudes of Africans brought to this country to be enslaved. He references the rationale used by Western society to justify its position of intellectual supremacy. Western ideologies are often formed around a heightened concept of self; it is based on a belief that the ultimate happiness of mankind is the sole purpose of the universe. These beliefs are in direct opposition to those of the Africans originally brought to this country, for whom the purpose of life was to appease the gods and live out a predetermined fate.

Baraka stresses a point made by Melville Herskovits, the anthropologist responsible for establishing African and African-American studies in academia, which suggests that value is relative or that "reference determines value". Although Baraka is not justifying the white supremacist views of the West, he does create a space to better understand the belief that one can be more evolved than a people from whom one differs very much. Likewise the author does not present the African system of belief in supernatural predetermination as better but speaks of how an awful violence is done against these people ideologically, by forcing them into a world that believes itself to be the sole judge of the ways in which proper existence must occur.

"The Negro as Property"

In chapter 2, "The Negro as Property", Baraka focuses on the journey from the African to the African American. He breaks down the process of the African's acculturation to show its complex form. Baraka begins with the initial introduction to life in America. He compares the African's immigrant experience to that of the Italian and Irish. He says the Italian and Irish came "from their first ghetto existences into the promise and respectability of this brave New World" (p. 12). Africans, on the other hand, came to this new world against their will. There was no promise or respectability in America for them, only force and abrupt change, and this defines the evolution of African-American culture.

After emancipation in 1863, the former slaves are being included in society. Baraka explains, these former slaves are no longer Africans. They are people of African descent who have, for generations, adapted to American culture. Their arrival and assimilation are most importantly not by choice. After being forcefully brought to America, the following generations are raised in a system that obliterates any trace of African culture. Children are immediately separated from their slave mothers at birth. They only learn stories and songs about Africa but lack the experience. Baraka states, "the only way of life these children knew was the accursed thing they had been born into" (p. 13). He shows that slavery is the most influential factor in African-American culture. He goes on to include the living conditions of slavery as an additional force. He refers to Herskovits's ideas to explain the dilution of African culture in the United States specifically. In the Caribbean and the rest of the Americas there are much heavier traces of African culture in the slave population. Herskovits explains this as a result of the master to slave ratio in these areas. In the United States the master to slave ratio was much smaller than in other regions of the New World, and is reflected in its form of a slave culture with constant association between the master and slave.

Baraka continues with a description of the effects of the "constant association" between African slaves and the culture of their white masters. This, he states, was a phenomenon confined to the United States. Whereas in the Caribbean and South America the majority of white slave owners had households wealthy enough to keep teams of hundreds of slaves, the American South maintained a class of "poor whites" who owned smaller groups of forced workers. In these smaller estates slaves would often be subjected to sexual abuse at the hand of their masters, as well as social cohabitation among small children (however black and white children would not attend the same schools.) Baraka asserts that a result of this "intimacy" was the alienation of African slaves from the roots of their culture—tribal references (as well as the "intricate political, social, and economic systems of the West Africans"—including trades such as wood carving and basket weaving) faded in the wake of American culture—relegated to the status as "artifact". He argues that only religious, magical, and artistic African practices (that do not result in "artifacts") survived the cultural whitewashing, standing as the "most apparent legacies" of the roots of African families made slaves.

"African Slaves / American Slaves: Their Music"

Jazz is recognized as beginning around the turn of the 20th century, but is actually much older. Most people believe that its existence derived from African slavery, but it has native African-American roots. Blues music gave birth to Jazz, and both genres of music stem from the work songs of the first generation of African slaves in America.

As slave owners forbade their slaves to chant and sing their ritualistic music, in fear of a rebellion, the original African slaves were forced to change their work songs in the field. The lyrics of their songs changed as well, as the original African work songs did not suit their oppressed situation. Jones states that the first generation of these slaves, the native Africans, truly knew the struggle of being forced into submission and stripped of their religion, freedoms, and culture. The music that formed as a result became a combination of the original African work songs and references to slave culture. Negroes in the New World transformed their language to be a mix of their own language and their European masters', which included Negro-English, Negro-Spanish, Negro-French, and Negro-Portuguese, all of which can be observed in their songs.

Storytelling was the primary means of education within the slave community, and folk tales were a popular and useful means of passing down wisdom, virtues, and so on from the elders to the youth. These folk tales also became integrated into their music and American culture, and later began to appear in the lyrics of blues songs.

Expression of oneself, emotions, and beliefs was the purpose of the African work song. Instruments, dancing, culture, religion, and emotion were blended together to form this representative form of music. Adaptation, interpretation, and improvisation lay at the core of this American Negro music. The nature of slavery dictated the way African culture could be adapted and evolved. For example, drums were forbidden by many slave owners, for fear of its communicative ability to rally the spirits of the enslaved, and lead to aggression or rebellion. As a result, slaves used other percussive objects to create similar beats and tones.

As the music derived from their slave/field culture, shouts and hollers were incorporated into their work songs, and were later represented through an instrumental imitation of blues and jazz music. Based on this, Jones declares that "the only so-called popular music in this country of any real value is of African derivation."

"Afro-Christian Music and Religion"

Christianity was adopted by the Negro people before the efforts of missionaries and evangelists. The North American Negroes were not even allowed to practice or talk about their own religion that their parents taught them. Specifically, in the south, slaves were sometimes beaten or killed when they talked about conjuring up spirits or the devil. Negroes also held a high reverence to the gods of their conquerors. Since their masters ruled over their everyday lives, Negroes acknowledge that the conqueror's gods must be more powerful than the gods they were taught to worship through discreet traditions. Christianity was also attractive to the Negroes, because it was a point of commonality between the white and black men. Negroes were able to finally imitate something valuable from their white slave owners. By accepting Christianity, Negro men and women had to put away a lot of their everyday superstitious traditions and beliefs in lucky charms, roots, herbs, and symbolism in dreams. Bakari felt white captors or slave masters exposed Christianity to the slaves because they saw Christianity as justification for slavery. Christianity gave the slaves a philosophical resolution of freedom. Instead of wishing to go back to Africa, slaves were looking forward to their appointed peaceful paradise when they meet their savior. Although they had to endure the harshness of slavery, the joy of living a peaceful life forever in eternity meant a lot more for them. As a result of accepting Christianity, slave masters were also happy that their slaves were now bound to live by a high moral code of living in order that they might reach the promised land. A lot of the early Christian Negro church services greatly emphasized music. Call-and-response songs were typically found in African services. Through singing of praise and worships songs in church, Negroes were able to express pent up emotions. African church elders also banished certain songs they considered "secular" or "devil songs" (p. 48). They also banished the playing of violins and banjos. Churches also began sponsoring community activities such as barbecues, picnics, and concerts, which allowed the Negro people to interact with each other. As time went by, African churches were able to produce more liturgical leaders such as apostles, ushers, and deacons. After the slaves were emancipated, the church community that was built by Negro leaders began to disintegrate because many began to enjoy the freedom outside of the church. As a result, some began listening again to the "devil's music" that was banned in the church and secular music became more prevalent.

"Slave and Post-Slave"

The chapter "Slave and Post-Slave" mainly addresses Baraka's analysis of the cultural changes Negro Americans had to face through their liberation as slaves, and how the blues developed and transformed through this process. After years of being defined as property, the Negro had no place in the post-slave white society. They had to find their place both physically, as they looked for somewhere to settle, but also psychologically, as they reconstructed their self-identity and social structure. Their freedom gave them a new sense of autonomy, but also took away the structured order of life to which they were accustomed. Baraka believes the Civil War and the Emancipation served to create a separate meta-society among Negroes, separating the Negroes more effectively from their masters with the institution of Jim Crow laws and other social repressions. The Reconstruction period brought about liberty for the American Negro and an austere separation from the white ex-slave owners and the white society that surrounded them. Organizations such as the KKK, Pale Faces, and Men of Justice emerged, seeking to frighten Negroes into abandoning their newfound rights, and to some extent succeeding. The Negro leaders — or educated, professional or elite Negro Americas such as Booker T. Washington— and many of the laws that were made to separate races at the time, divided blacks into different groups. There were those who accepted the decree of "separate but equal" as the best way for the Negro to live peacefully in the white order, and those who were separate from white society. After the initial period following the Emancipation, songs that arose from the conditions of slavery created the idea of blues, including the sounds of "shouts, hollers, yells, spirituals, and ballits", mixed with the appropriation and deconstruction of white musical elements. These musical traditions were carried along the post-slavery Negro culture, but it had to adapt to their new structure and way of life, forming the blues that we recognize today.

"Primitive Blues and Primitive Jazz"

The chapter "Primitive Blues and Primitive Jazz" refers to Baraka's breakdown of the development of blues — and jazz as an instrumental diversion — as Negro music through the slave and especially post-slave eras, into the music that we would consider blues today (its standardized and popular form). After Emancipation Negroes had the leisure of being alone and thinking for themselves; however, the situation of self-reliance proposed social and cultural problems that they never encountered as slaves. Both instances were reflected in their music, as the subject music became more personal and touched on issues of wealth and hostility. The change among speech patterns, which began to resemble Americanized English, also created a development in blues as words had to be announced correctly and soundly. With Negro singers no longer being tied to the field, they had an opportunity to interact with more instruments; primitive or country blues was influenced by instruments, especially the guitar. Jazz occurs from the appropriation of this instrument and their divergent use by blacks, with elements like "riffs", which gave it a unique Negro or blues sound. In New Orleans blues was influenced by European musical elements, especially brass instruments and marching band music. Accordingly, the uptown Negroes, differentiated from the "Creoles" — blacks with French ancestry and culture, usually of a higher class — gave a more primitive, "jass" or "dirty" sound to this appropriated music; which gave blues and jazz a distinct sound. Creoles had to adapt to this sound once segregation placed them on the same level as all other freed black slaves. The fact that the Negro could never become white was a strength, providing a boundary between him and the white culture; creating music that was referenced by African, sub-cultural, and hermetic resources.

"Classic Blues"

Baraka starts the chapter with marking it as the period where classic blues and ragtime proliferated. The change from Baraka's idea of traditional blues to classic blues represented a new professional entertainment stage for African-American art. Prior to classical blues, traditional blues' functionality required no explicit rules, and therefore a method didn't exist. Classic blues added a structure that was not there before. It started becoming popular with the change in minstrel shows and circuses. Minstrel shows demonstrated recognition of the "Negro" as part of American popular culture, which though it always had been, was never formally recognized. It was now more formal. Minstrel shows, despite the overall slanderous nature towards African Americans, were able to aid in the creation of this new form. It included more instruments, vocals and dancing than the previous blues tradition. Blues artist like Bessie Smith in "Put it Right Here or Keep It Out There" were presenting an unspoken story to Americans who have not heard of or had ignored it. He makes the distinction between blues, which he ties to slavery, and ragtime, which he claims to have more European musical ties. Baraka notes that this more classic blues created more instrumental opportunities for African Americans, but on the other hand instruments such as the piano were the last to incorporate and had a much more free spirited melody than the other instruments or compared to ragtime. Even with these new sounds and structure, some classic blues icons remained out of the popular music scene.

"The City"

The "Negroes" were moving from the south to the cities for jobs, freedom and a chance to begin again. This, also known as a "human movement", made jazz and classical blues possible. They worked the hardest and got paid the least. Ford played an important role with their transition because it was one of the first companies to hire African Americans. They even created the first car that was available for purchase for African Americans. Blues first began as a "functional" music, only needed to communicate and encourage work in the fields, but soon emerged into something more. Blues music became entertaining. It morphed into what was called "the 'race' record", recordings of music targeted towards African Americans. Mamie Smith was the first African American to make a commercial recording in 1920. She replaced Sophie Tucker, a white singer who was unable to attend due to illness. After that, that "Jazz Age" began, otherwise known as the "age of recorded blues". Soon, African American musicians began being signed and selling thousands of copies. Their music began to spread all over. Companies even began hiring African Americans as talent scouts. To the surprise of many, African Americans became the new consumers in a predominantly white culture. Blues went from a small work sound to a nationwide phenomenon. Musicians in New York were very different from the ones in Chicago, St. Louis, Texas and New Orleans; the music of performers of the east had a ragtime style and was not as original, but eventually the real blues was absorbed in the east. People were only really able to hear the blues and real jazz in the lower-class "gutbucket" cabarets. World War I was a time where the Negroes became mainstream in American life. Negroes were welcomed into the services, in special black units. After World War I, there were race riots in America and Negroes started to think of the inequality as objective and "evil." Because of this, many groups were formed, such as Marcus Garvey's black nationalist organization, and also other groups that had already been around, like the NAACP regained popularity. Another type of blues music that came to the cities was called "boogie woogie", which was a blend of vocal blues and early guitar techniques, adapted for the piano. It was considered a music of rhythmic contrasts instead of melodic or harmonic variations. On weekends, Negroes would attend "blue light" parties. Each featured a few pianists, who would take turns playing while people would "grind". In 1929, the depression left over 14 million people unemployed and Negroes suffered most. This ruined the blues era; most night clubs and cabarets closed and the recording industry was destroyed. Events that shaped the present day American Negro included, World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II, and the migration to the cities.

"Enter the Middle Class"

"The movement, the growing feeling that developed among Negroes, was led and fattened by the growing black middle class".[2]

In Chapter 9, Baraka's focus is on the cause and effect of the black middle class in the North. Negroes who held positions, such as house servants, freedmen and church officials, were seen as having a more privileged status among Negroes of this time. These individuals embodied the bulk of the black middle class. Although Negroes attempted to salvage their culture in the North, it was impossible to be free of the influence of "white America", drowning out the Negroes' past. The black middle class both responded and reacted to this by believing their culture should be completely forgotten, trying to erase their past and culture completely to be able to fit in. This, in turn, contributed to the growing support for cutting off Southerners in order to have a life in America. This divided and separated blacks, physically and mentally. All in all, the black middle class' attempt to fit into America around them, caused them to conform their own black culture, to the white culture that surrounded them. Not only did they attempt to change music, but media such as paintings, drama and literature changed, as a result of this attempt to assimilate into the culture around them.

"Swing—From Verb to Noun"

In this chapter, Baraka illustrates the importance of Negro artist to be a "quality" black man instead of a mere "ordinary nigger". Novelists such as Charles Chesnutt, Otis Shackleford, Sutton Griggs, and Pauline Hopkins demonstrated the idea of social classes within the black race in literature, similar to that of the "novel of their models", the white middle class. The separation created within the group gave a voice to the house servant. As the country became more liberal, in the early 1920s, Negroes were becoming the predominant urban population in the North, and there was the emergence of the "New Negro". This was the catalyst for the beginning of the "Negro Renaissance". The Negro middle-class mindset changed from the idea of separation, which was the "slave mentality", into "race pride" and "race consciousness", and a sense that Negroes deserved equality. The "Harlem School" of writers strove to glorify black America as a real production force, comparable to white America. These writers included Carl Van Vechten, author of the novel Nigger Heaven. Since the Emancipation, the blacks' adaptation to American life had been based on a growing and developing understanding of the white mind. In the book, Baraka illustrates the growing separation, in New Orleans between the Creoles, gens de couleur, and mulattoes. This separation was encouraged as a way to emulate the white French culture of New Orleans. Repressive segregation laws forced the "light people" into relationships with the black culture and this began the merging of black rhythmic and vocal tradition with European dance and march music. The first jazzmen were from the white Creole tradition and also the darker blues tradition. The music was the first fully developed American experience of "classic" blues.

In the second half of this chapter, Baraka breaks down the similarities and differences between two jazz stars: Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke. "The incredible irony of the situation was that both stood in similar places in the superstructure of American society: Beiderbecke, because of the isolation any deviation from mass culture imposed upon its bearer; and Armstrong, because of the socio-historical estrangement of the Negro from the rest of America. Nevertheless, the music the two made was as dissimilar as is possible within jazz."[3] He goes on to draw a distinction between what he identifies as Beiderbecke's "white jazz" and Armstrong's jazz, which he sees as being "securely within the traditions of Afro-American music". Moreover, Baraka's broader critique of the place of Negro music in America is emphasized when he claims sarcastically, despite Beiderbecke's white jazz being essentially "antithetical" to Armstrong's, that "Afro-American music did not become a completely American expression until the white man could play it!"[4] Baraka then goes on to chart the historical development of Armstrong's music as it became influenced by his performances and recordings with the Hot Five. He notes that though previous jazz bands were focused on an aesthetic based on a flexible group improvisation, Armstrong's presence in the Hot Five changed the dynamic of play and composition. Instead of a cohesive "communal" unit, the other members followed Armstrong's lead and therefore, he claims, the music made by the Hot Five became "Louis Armstrong's music".[5]

Baraka goes on to write about the rise of the solo jazz artist and specifically Armstrong's influence on the tendencies and styles of jazz bands all over. His "brass music" was the predecessor of music featuring reed instruments that would follow. He writes about the bands playing in the 1920s and '30s and how the biggest and best of them were run and organized by predominately college-educated black men. These men worked for years to grow the music and integrate new waves of style as much as they could without sacrificing the elements that were so important to the identity of the music. Furthermore, Baraka writes about Duke Ellington's influence being similar in magnitude to Armstrong's but in a different way. He sees Ellington as perfecting the "orchestral" version of an expressive big band unit, while maintaining its jazz roots.

After this, much of the white middle-class culture adopted a taste for this new big band music that had the attitude and authenticity of the older black music but was modified, in part, to suit the modern symphony-going listener. This started transforming into the well-known swing music. When there became a market for this particular taste, white bands started trying to appropriate the style for the sake of performance and reaching broader audiences (a testament to the growing influence and significance of the Negro music movement). Unfortunately, Baraka points out, with the explosion in popularity, the industry for recording and producing music of this kind became somewhat monopolized by wealthy white record labels and producers. There was widespread discrimination against black performers, even after labels would pay good money for original scores written by someone else. This discrimination was evident too in the subsequent alienation of many Negro listeners, who became turned off by the appropriation and new mainstream success of what they felt and saw as their own music.

"The Blues Continuum"

Large jazz bands had begun to replace traditional blues, which had begun to move to the underground music scene. Southwestern "shouting" blues singers developed into a style called rhythm and blues, which was largely huge rhythm units smashing away behind screaming blues singers. The performance of the artists became just as important as the performance of the songs. Rhythm and blues, despite its growth in popularity, remained a "black" form of music that had not yet reached the level of commercialism where it would be popular in the white community. The more instrumental rhythm and blues use of large instruments complemented the traditional vocal style of classic blues. It however differed from traditional blues by having more erratic, louder percussion and brass sections to accompany the increased volume of the vocals. Rhythm and blues had developed into a style that integrated mainstream without being mainstream. With its rebellious style, rhythm and blues contrasted the mainstream "soft" nature of Swing with its loud percussion and brass sections, and because of its distinctive style remained a predominantly "black" form of music that catered to an African American audience. There was divide however between the middle class of African Americans, who had settled upon mainstream swing and the lower class, who still had a taste for traditional country blues. Over time, the mainstream sounds of swing became embedded so far into rhythm and blues that it became indistinguishable from its country blues roots and into a commercialized style.

"The Modern Scene"

As white Americans adopted styles of blues and adopted this new expression of music, jazz became the more accepted "American" music, which related to a broader audience and was accepted for commercial use. Through this evolution of blues into jazz and this idea that jazz could be more socially diverse and appeal to a broader range of Americans, blues started to become less appreciated while jazz represented the "true expression of an American which could be celebrated". Copying the oppressive ideas that segregated the people between white and black blues was devalued and the assimilation of both African Americans and their music into being considered "American culture" was next to impossible. As years went on there was a failure to see that the more popular mainstream sounds of swing and jazz and "white" wartime entertainment was a result of the black American tradition, blues created by the very people that America was trying so hard to oppress. In efforts to try to re-create their own sound once more and create their own culture of music, they began with their roots in blues and evolved their sounds of the past into a new sound, bebop.References:

New York: William Morrow & Company, 1963. ISBN 0-688-18474-X

Baraka, Amiri (1999). Blues People: Negro Music in White America. Harper Perennial. p. 123. ISBN 978-0688184742.

Baraka (1999). Blues People. p. 154.Baraka (1999). Blues People. p. 155.

William J. Harris is an emeritus professor of American literature, African American literature, creative writing, and jazz studies. He taught at the University of Kansas, Pennsylvania State University, and Cornell University, among other universities. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of the acclaimed critical text on Amiri Baraka's work (University of Missouri Press, 1986).

Amiri Baraka, Black Music, and Black Modernity

Amiri Baraka is undoubtedly one of the most central figures of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S as well as a key literary and cultural figure post World War II. Baraka’s politics and aesthetics, though ever evolving over his career, have solid consistencies throughout. These come in the form of his deep engagement with Black musical practices and formations. This is where James Smethurst’s Brick City Vanguard begins. “The first thing to say is that Amiri Baraka loved “the music”, which was jazz in the first place but also almost all forms of [B]lack music.” What this text asks us to consider is Baraka’s music writing, including writing on liner notes and a serious consideration of the popular Black musical form. To this end, I would situate this text as something that speaks to and against a tradition of anti-popular music writing, though I would argue anti-Black-popular music writing, fronted by the likes of Theodor Adorno who disparaged the work of jazz. Smethurst positions Baraka early on in relation to other thinkers as well, noting, “Unlike Stuart Hall, who famously claimed that he “doesn’t give a damn” about popular music except as a site or arena for political contestation, a place “where socialism might be constituted (a claim that I do not really believe, given Hall’s early fondness for jazz, especially the work of Miles Davis), Baraka would not have advanced such an argument.”

James Smethurst’s Brick City Vanguard is essential reading for anyone engaged in the life of Amiri Baraka or the Black Arts Movement. Further, anyone interested in the various ways in which music is thought and written about would find this text a most useful resource. This text is an attempt to open up, or at the very least, expound on a conversation about the ways in which we read Baraka’s work on art and music (influenced by Amina Baraka), and the changes over his career of his performance and literary writing. Smethurst also wants us to think about what music is, what music does, and how music does it, through Baraka’s writing. I think what is interesting is the site of the funeral as a place to bear witness to the reach and scope of the work Baraka made over his lifetime. It is here where we see the extent of his politics – union members, teachers, socialists, communists, musicians, poets, and artists. This is a testament to what constitutes the range of work Baraka influenced, but more importantly, this speaks to Baraka’s impossibly profound legacy. In the closing stanzas Smethurst notes

Looping back to Symphony Hall and what Amiri Baraka’s funeral might indicate about how to assess that career and contributions, one might recall again Baraka’s declaration that Newark embodied for him “a measure, a set of standards and life influencing principles.” Given his ability to sometimes talk about himself and his past as if he he were standing outside himself, passing judgement on his successes and failures, one could easily imagine him sitting in the audience of his own funeral, joking with the people onstage, looking around at the composition of the crowd, and concluding that his work had connected with the blues people of Newark and helped them survive and potentially even more forward.

This section exemplifies much of what Smethurst attempts to work through here. He explores the range of influences on Amiri Baraka and the absolute mass of people who he influenced as well. This book is as much about the man Amiri Baraka as it is about the place Brick City. It is an astute assessment of the importance of the relationship between Baraka and Newark, showing how and why this place held such a deep significance for Amiri and Amina Baraka. It is an attempt at showing exactly the kind of vitally important work that happens outside of the central art metropoles like Harlem.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Wilton Schereka is a PhD student in Africana Studies at Brown University. He is a graduate of the University of the Western Cape, where he obtained a Master of Arts in History, an Honors degree in English literature, a certificate in English and History education, and a Bachelor of Arts in English and History. His academic interests include black radical philosophy, the movement of philosophies between Africa's diasporas and the continent, aurality, sound, music, and visions of the postcolonial moment.

Black History Meets Black Music: 'Blues People' At 50

PHOTO: Amiri Baraka leaves the polling place after voting in Newark, N.J., in 2010. Amiri's son, Ras Baraka, is currently running for mayor. Patti Sapone/Star Ledger/Corbis

The year 1963 saw the March on Washington, the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and Medgar Evers, the bombing of the Birmingham church that resulted in the deaths of four black girls and the passing of W.E.B. Du Bois. That same year, LeRoi Jones — a twentysomething, Newark, N.J.-born, African-American, Lower East Side-based Beat poet — published a book titled Blues People: a panoramic sociocultural history of African-American music. It was the first major book of its kind by a black author, now known as Amiri Baraka. In the 50 years since, it has never been out of print.

"The book was originally titled Blues: Black and White," says Baraka, now 78, by phone from Newark, while he was working on his son Ras Baraka's mayoral campaign. "But I changed it because I wanted to focus on the people that created the blues. And that was the real intent of that title: I wanted to focus on them — us — the creators of the blues, which is still, I think, the predominate music under all American music. It cannot be dismissed, even though you might give it to some pop singer, they change it around. But it will come out. It will be heard."

Blues People argues that in their art, Louis Armstrong, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and countless other black bards confronted the forces of racism, poverty and Jim Crow. This gave birth to work songs, blues, gospel, New Orleans jazz, its Chicago and Kansas City swing extensions, the bebop revolution (which in turn spawned the so-called cool and hard bop schools), and the then-emerging avant-garde of the late '50s and early '60s, characterized by the forward-thinking artistry of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor. For Baraka, jazz is "the most cosmopolitan of any Negro music, able to utilize almost any foreign influence within its broader spectrum" — a cultural achievement Baraka says was downplayed and ignored by Eurocentric whites.

"They have to do that to make themselves superior in some kind of way: that everything has come from Europe, which is not true," Baraka says. "And if you study, you'll see [the Africanisms] even in the way Americans talk; it's quite unlike English [from Great Britain]. And certainly the music has been one abiding register of Afro-American influence."

Baraka wrote that Blues People was a "theoretical endeavor" that "proposes more questions than it will answer" about how descendants of enslaved Africans created a new American musical genre and turned "Negroes" into "African Americans" in the process. That message still resonates deeply with many scholars, including Ingrid Monson, a professor of African-American music at Harvard University and author of Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Call Out to Jazz and Africa.

"I assign portions of this book in virtually every course I teach," Monson wrote in Blues People: Amiri Baraka As a Social Theorist, a speech she delivered in 2004, "to remind my students that cultural studies and critical race theory didn't begin in the academy, but in 20th-century African-American thought and intellectual practice from DuBois to Garvey, Locke, Ellington, Ellison and Baraka."

You've Got To Be Modernistic

Baraka was certainly not the first black writer to write about African-American music. But it was his modern stance, propelled by the momentum of the Civil Rights Era, that made his analysis unique.

"[Early works by black authors] primarily focused on the written tradition of African-American music, as part of the Western art music tradition," says University of Pennsylvania professor Guthrie Ramsey, author of Bud Powell: Black Genius, Black History and the Challenge of Bebop. "The goals of those books were to position black music within Western culture. There weren't many black writers who had the platforms like Baraka was developing at that time. He wrote that book from [a contemporary] African-American perspective. And that's what made it unique at that time.

"Blues People was out there not entirely by itself — Ralph Ellison had written some essays on jazz here and there and a few others," says fellow historian A.B. Spellman, author of Four Jazz Lives. "But Blues People certainly was the first one to take a comprehensive look at the music: where it came from, the people who made it and the culture that produced it. So in that sense it was a trailblazing book. And still remains a strong read today."

Baraka — as LeRoi Jones — came from a middle-class upbringing, including university studies at Rutgers, Columbia and Howard Universities. But he also served in the Air Force, married Jewish writer Hettie Cohen and published a critically acclaimed 1961 work, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, which established him as a noteworthy figure among the Beat Generation. It was the influence of the late poet Sterling Brown, who taught generations of Howard students — including Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison and conservative economist Thomas Sowell — who gave Baraka the impulse to investigate the older folk traditions of African-American music.

"I always liked jazz," Baraka says. "And my people liked the old blues, race records and the doo-wop and all that. But when I went to Howard, the great Sterling Brown was a great influence on many of us. A.B. Spellman and I, Toni Morrison ... a lot of us sat up under Brown. And so, you can always tell that influence.

"We thought we knew so much about jazz. [Brown] said, 'Why don't you come on by my house, I'll show you some things.' We went by there, and he had the whole wall full of records, by chronology and genre, and he said to me, 'That's your history.' So it took me a decade to find that those records told a story: Every voice, every title is telling you the story of Afro-American history. I really latched on to that idea. And I went back and started listening to the blues."

"[Professor Brown] knew the music very well — particularly the great heroic bands like [Duke] Ellington, [Don] Redman, [Jimmie] Lunceford and [Count] Basie, and so forth," Spellman says. "And he was always very insistent that we know the music of the founders, and to know why their music endures, and what made that music. He was a terrific mind: a person with a good, clear and solidly based intellect."

Call And Response

Inspired by Brown, Baraka's Blues People spoke forcefully about the art black people produced — and the pain they endured in this country — and was well-received by black and white critics. Langston Hughes hailed it as "a must for all who would more knowledgeably appreciate and better comprehend America's most popular music."

Not everyone was convinced. In his 1964 book of essays Shadow and Act, novelist Ralph Ellison wrote that "[t]he tremendous burden of sociology, which Jones would place upon this body of music, is enough to give even the blues the blues."

"He put my book down in his book," Baraka says, still stinging from Ellison's criticism five decades later. "I came with a sociological analysis of the blues that he didn't want to accept. He had a romantic kind of conception: The blues is just music that comes out of... But I was trying to find out why. [Sterling] Brown said if you study the actual music and the lyrics, they're talking about their lives. What do you think they're talking about? Some fantasy world? They're talking about their lives in America. And for Ralph not to understand that I think was a fundamental flaw in his understanding."

Today's scholars might take issue with the exact nature of Baraka's argument. Ingrid Monson's paper points out the author's "tendency toward social determinism [that] is particularly obvious in Baraka's discussion of class — which, to me, is where his argument is most undermined by essentialism. Here, middle-classness is the ultimate marker of cultural inauthenticity, because the black middle class, according to Baraka, dedicated itself to assimilation."

But Monson offers praise for the book in general. "Blues People is a brilliant and path-breaking book, not because all of its factual information is correct, or because all of its interpretive perspectives are unassailable, but because of the sheer audacity, scope and originality of its interpretive perspective," she wrote.

Becoming Baraka

Blues People outlined a black experience in sound, and it marked the beginning of LeRoi Jones' social and personal metamorphosis. His drama and fiction works grew increasingly centered on African-American themes. He moved from Manhattan's Lower East Side to predominantly black Harlem. He founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre and School in 1965 and, along with poet and critic Larry Neal, kick-started the Black Arts movement — a cultural arm of the Black Power movement. And, in 1968, Jones changed his name to Imamu Ameer Baraka, and later dropped Imamu (meaning "spiritual leader") and changed Ameer to Amiri. He would later move from Harlem back to his hometown of Newark, participate in the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Ind., and reject the narrow confines of cultural nationalism for Marxist-Leninist doctrines.

From the '70s to today, Baraka remains prolific, and has written an autobiography, essays and poetry. He's continued to publish books about music. But by far, Blues People remains his most influential work about music.

"You'd be hard-pressed to think about who has not been influenced by that book — anyone from Sterling Stuckey to Samuel Floyd, Ingrid Monson, Scott DeVeaux and myself," Guthrie Ramsey says, listing fellow scholars. "That book created a space in what I call the literary community theatre for all kinds of ruminations on black music." For Ingrid Monson, "[t]he speculative history of African-American music that [Baraka] presented in Blues People in 1963 successfully articulated a number of crucial issues that foreshadow recent work in cultural studies, post-structuralism, anthropology and ethnomusicology."

A.B. Spellman says a 2013 version of Blues People would naturally be different, but the focus on black experiences would remain. "A young writer trying to do a comprehensive book on African-American serious music would want to have a clear look at the sociopolitical environment of the music today," Spellman says. "It's a different one from the environment Blues People was written in, but no less exploitative; no less cynical, and it needs a different analysis. And you'd want to have a sense of pride, because African-American music has affected the culture of the world, and continues to do so. I would not attempt to be neutral."

As for the author, Baraka himself notes with satisfaction that the music and culture of "blues people" enjoys a wider influence in the 21st century than it did in 1963. "My own thinking has evolved," Baraka says. "You find Africanisms in American speech. You find an African influence on United States culture. There are all kinds of Africanisms in America, as you would expect, if you really thought about it. ... That whole thing is much broader; the influence is much broader than I first understood."

October 3, 2013

The Blues People 50 Years Later

Description

Inspired by Amiri Baraka’s Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963), a generation of scholars in the field of Jazz and Blues music history and criticism was born, creating a legitimate space in the academy for the serious study of African American music. Joining Amiri Baraka in this conversation-- reflecting on the years between Baraka’s Blues People and his Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Music -- will be two major scholars in this field: Ingrid Monson and John Szwed.

Fifty years ago Blues People was the first book-length history written by an African American that addressed the social, musical, economic, and cultural influences of the blues and jazz on American history. His approach to music criticism was different from anything else that existed when he first began writing in the 1950s and 60s, partly because he was the only black writer in a field of white critics. Furthermore, he was not simply describing the music, but he was also fashioning a type of prose writing that was itself an artistic performance about music.

Speakers

-

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka is one of the most respected and widely published African-American writers. With the beginning of Black Civil Rights Movements during the sixties, Baraka explored the anger of African-Americans and used his writings as a weapon against racism. Also, he advocated scientific socialism with his revolutionary inclined poems and aimed at creating aesthetic through them. Amiri Baraka’s writing career spans over nearly fifty years and has mostly focused on the subjects of Black Liberation and White Racism. He is counted among the few influential political activists who have spent most of their lifetime fighting for the rights of African-Americans.

-

Ingrid Monson

Harvard University

Dr. Ingrid Monson is the Quincy Jones Professor of Jazz at Harvard and the author of Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Call out to Jazz and Africa. She has a Ph.D. and an M.A. in Musicology from NYU, and a B.M. from New England Conservatory. Professor Monson won the Sonneck Society's 1998 Irving Lowens Prize for the best book in American music for her 1996 Saying Something, Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. She was also a founding member of the nationally known Klezmer Conservatory Band, and plays trumpet with jazz and salsa bands. She is working on a book on the music of the African Diaspora.

-

John Szwed

Columbia University

Dr. John Szwed is the Director of Jazz Studies at Columbia where he is also Professor of Music and Jazz Studies and the author of Jazz 101. Dr. Szwed’s publications range from anthropological studies of Newfoundland and the West Indies to record liner notes and jazz journalism. Before he joined Columbia, Szwed taught Anthropology, African American Studies, and Film Studies for many years at Yale University, and also received fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller foundations. He is President of the non-profit music production company Brilliant Corners, which is based in New York City.

Video Recording:

Fifty years ago Blues People was the first book-length history written by an African American that addressed the social, musical, economic, and cultural influences of the blues and jazz on American history. His approach to music criticism was different from anything else that existed when he first began writing in the 1950s and 60s, partly because he was the only black writer in a field of white critics. Furthermore, he was not simply describing the music, but he was also fashioning a type of prose writing that was itself an artistic performance about music.

Amiri Baraka’s ‘Blues People’ Comes Home to the Apollo

The trumpeter and composer Russell Gunn will premiere “The Blues and Its People,” a suite inspired by Baraka’s influential text, to mark its 60th anniversary.

When he first read Amiri Baraka’s epochal study “Blues People: Negro Music in White America,” originally published in 1963, Russell Gunn felt that he already understood, on some level, the book’s urgent themes. That’s not just because “Blues People”— which centers the blues as the foundation of American music, and the lives of Black Americans as the foundation of the blues — has been widely influential, shaping public and institutional understanding of the history of the blues, jazz and American culture.

While growing up in East St. Louis in the 1970s and early ’80s, Gunn — the trumpeter, composer and bandleader — had always felt that truth already, in a way he links to ancestral memory.

“When the teacher would leave the classroom, all of us would beat rhythms on our desk,” Gunn recalled in a late January Zoom interview from his Atlanta home. “Somebody would rap, and then we’d take turns. This is what we did naturally, before we knew anything about New York, or people getting signed for their rapping. We’d never heard of a drum circle, never heard of a djembe or a griot.”

That experience exemplifies deeper aspects of the theories that Baraka, who died in 2014, first laid out in “Blues People” and then explored the rest of his life: that the music’s history is an ongoing community narrative of a people and their adaptation to and adoption of American life. It’s a story forged not just by African roots — work songs and church choirs, field calls and bebop, storied blues and jazz masters. Instead, it’s a history still being lived and written, wherever its people gather and make it.

The Apollo Theater stands singular among those gathering spots. On Saturday, Gunn and his genre-defying big band, the Royal Krunk Jazz Orkestra, will premiere his Baraka-inspired suite, “The Blues and Its People,” at the Harlem institution. A host of soloists and performers, many with deep connections to Baraka, will augment the 24-member band: the saxophonist and poet Oliver Lake, the singer Jazzmeia Horn, the trombonist Craig Harris, the Grammy-winning vibraphonist Stefon Harris, the poet Jessica Care Moore and the West African djembe player Weedie Braimah.

“Baraka’s book starts with a call and response,” said Leatrice Ellzy, the Apollo’s senior director of programming, who commissioned the work. “In the tradition of Black folk, call-and-response and the drum beats throughout our entire being, in the rhythm of how we speak, in artistic pieces and on that Apollo stage.”

Dr. Fredara Hadley, an ethnomusicology professor at Juilliard, noted, “You can’t have call-and-response off by yourself.” When she teaches “Blues People,” a book she finds continually rewarding and challenging, Hadley emphasizes Black Americans’ “ongoing engagement with Africa and African music, generations after enslavement ends.”

“It’s asking, ‘What and where is home?’” she said. “The music’s part of the grass-roots exercises of creating one’s world, fashioning one’s self and making one’s self whole, all inside a community space. The music is the medicine.”

That echoes Baraka’s own call for “art for the sake of evolution” — as in art expressive of and directed to community — made from the Apollo stage as he introduced the consciousness-raising Last Poets collective in 1972.

Gunn called that stage “the mecca of what I represent as a musician.” He has blended jazz and hip-hop since the ’90s, notably on his Grammy-nominated “Ethnomusicology” album series. On its three albums and occasional live performances, the Atlanta-based RKJO performs with grit and power, a keen sense of jazz history, a searching cosmic-mindedness and pure funk with roots in Southern hip-hop.

Gunn credits Ronald Carter, his band director at East St. Louis Lincoln Senior High School, with showing him that despite clear harmonic and rhythmic differences, the music that they played in school was not fundamentally different from the music on the radio, or in his grandmother’s church. “It’s all part of the same continuum,” Gunn said. And he credits Branford Marsalis with reminding him, when Gunn played in Marsalis’s ’90s jazz-meets-hip-hop ensemble Buckshot LeFonque, how to play music “that’s serious, deep and meaningful” without being “pure self-indulgent [expletive].”

Gunn laughed recalling how some RKJO members have complained about how difficult his compositions can be to master. “This is high level music for sure,” he said, “but it’s still music, and it’s still for the people.”

That idea is at the heart of both Baraka’s book and Gunn’s

suite. “What kind of music do you play?” asks Oliver Lake, in his poem

“Separation,” now the centerpiece of the final movement of “The Blues

and Its People.” Lake’s answer: “The good kind!” The poem is a blazing

statement of how “labels” divide and separate, how “Aretha Franklin and

Sun Ra are the same” and how Lake prefers “all my food on the same

plate.”

“All of it is valid,” Lake said late last month in a

spirited Zoom round table interview with musicians collaborating on the