https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/20/opinion/trump-manafort-lobbying.html

Guest Essay

If Donald Trump Wins, Paul Manafort Will Be Waiting in the Wings

by Brody Mullins and Luke Mullins

June 20, 2024

New York Times

[Brody Mullins is an investigative reporter who covers business, lobbying and campaign finance. Luke Mullins is a journalist who focuses on politics and power in Washington, D.C.]

A few years ago, Paul Manafort was a disgraced political operative living in a windowless cell. If Donald Trump wins in November, Mr. Manafort is likely to re-emerge as one of the most powerful people in Washington.

Because of Mr. Trump’s transactional nature and singular method of wielding power, as president, he would probably empower a small group of lobbyists who could profit from their access. Though no one elected them, these gatekeepers could exercise sweeping influence over U.S. policy on behalf of corporations and foreign governments, at the expense of regular Americans who can’t afford their services.

Rather than drain the swamp, an unleashed President Trump would return the lobbying industry to the smoke-filled rooms of the 1930s, an era unchallenged by the decades of reforms since Watergate.

And Mr. Manafort, whose career has been based on lobbying the same people he helped put in office, would be at the center. “A new Trump administration would be a bonanza for Paul,” says Scott Reed, a Republican political strategist who hired Mr. Manafort to work on Bob Dole’s 1996 presidential campaign. “Trump is the Manafort model: access at the highest levels for his clients and friends.”

A second Trump term, with the likelihood of yes-men and lackeys having more sway than political professionals and civil servants, would all but return Washington to an era when the nation’s laws were negotiated over steak dinners and golf. In the early 1970s, the leaders of a U.S. tool and die company worried about losing a Defense Department contract. They met with the era’s top lobbyist, Tommy Corcoran, who had worked in the White House for President Franklin Roosevelt and later advised Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

Mr. Corcoran picked up the phone and called a Pentagon contact. After a brief exchange, he hung up. “Your problems are over,” he told his new clients. His $10,000 bill is roughly the equivalent of $75,000 today.

After Watergate, voters elected lawmakers who took federal power out of the hands of the president and congressional leaders and spread it out among legislative committees, subcommittees and other officials. That spelled the end of the Corcoran era. No lobbyist, no matter how connected or wealthy, could get anything done alone.

Over 50 years, Washington’s lobbying industry evolved from a tiny club of well-connected insiders to a sophisticated economy of P.R. gurus, social media experts, political pollsters, data analysts and grass-roots organizers. That development was encouraged by a major ethics reform law passed by Congress in 2007 that sought to diminish personal ties by prohibiting members of Congress or government officials from receiving dinners, golf outings, sports tickets and anything else of value from lobbyists.

When Mr. Trump took office in 2017, the old cozy club reasserted itself. He reconsolidated federal policymaking in the Oval Office. For lobbyists, Congress no longer mattered as much. Neither did most of the executive branch. The only person who mattered in Washington was Mr. Trump. And the most effective way to lobby him was the most straightforward: hire someone who knew him well.

America’s founders envisioned that lobbyists would work to bend government policy to their liking. In the Federalist Papers, James Madison predicted that advocates for many interest groups, which he called factions, would be equally balanced and free to compete with one another in an open market of ideas. Corporate interests would battle with organized labor. Consumer groups would face off with representatives of industry.

The way Mr. Trump seems likely to govern gives lobbyists for certain well-heeled companies and countries a huge advantage. Fewer members of Congress and government officials would have the opportunity to weigh in. The same goes for interest groups. It is unlikely to be the kind of fair fight Madison expected. Look how Mr. Trump backed off his opposition to TikTok after the Club for Growth hired his former adviser Kellyanne Conway to be an advocate for the company.

Mr. Manafort learned the value of access while working on Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election. Then 31 years old, Mr. Manafort formed a lobbying firm with the Reagan aides Roger Stone and Charlie Black, which became the dominant outfit of the Reagan era. (Mr. Trump was a client.) The lobbyists created a legally separate firm to help Republicans win office. Employees of the firms had a saying: “Elect ’em on the second floor. Lobby ’em on the third floor.”

In the mid-2000s, Mr. Manafort moved the model overseas. After helping elect Viktor Yanukovych as prime minister of Ukraine in 2006 and president in 2010, Mr. Manafort made around $60 million in fees and loans from oligarchs close to Mr. Yanukovych, according to legal filings. That money train stopped in 2014 after Mr. Yanukovych was ousted from power.

Mr. Manafort returned to the United States deeply in debt and without any major source of income. In the spring of 2015 his wife, Kathy, confronted him about an affair with a woman more than three decades his junior. He broke down, begged his wife for forgiveness and checked into an Arizona sex addiction clinic.

He saw Mr. Trump’s 2016 White House bid as his path to redemption. Mr. Manafort secured a salary-free job on the team, and when the campaign manager was fired that June, Mr. Manafort got the top post.

Nearly everyone who works for a presidential campaign hopes to land a job in the administration. Instead, Mr. Manafort’s primary objective, his longtime deputy Rick Gates told us when we interviewed him for our book, was to get Mr. Trump elected so that he could use his new lobbying clout to escape his financial hole. “He was immediately thinking about how to monetize this,” Mr. Gates said.

At one point during the campaign, according to Mr. Gates, who later testified against Mr. Manafort in federal court, the would-be president approached Mr. Manafort with a question: “Hey, if we actually win this thing, what cabinet position do you want? I’ll give you anything that you want.” Mr. Manafort said he had no interest. For this inveterate political hustler, there was only one destination after a successful presidential campaign: K Street.

Things didn’t work out as Mr. Manafort had hoped, of course. He was forced to step down as campaign chairman amid a firestorm over his work for pro-Russian interests in Ukraine. As a result, he soon emerged as a central figure in Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russia’s influence on the 2016 election.

The eventual charges against him weren’t directly related to interference in the election. In 2018 he was convicted of or pleaded guilty to numerous federal counts mostly related to his work in Ukraine, including tax fraud and bank fraud, and was sentenced to more than seven years in prison.

Paul John Manafort Jr. (/ˈmænəfɔːrt/; born April 1, 1949) is an American former lobbyist, political consultant, and attorney. A long-time Republican Party campaign consultant, he chaired the Trump presidential campaign from June to August 2016. Manafort served as an adviser to the U.S. presidential campaigns of Republicans Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Bob Dole. In 1980, he co-founded the Washington, D.C.–based lobbying firm Black, Manafort & Stone, along with principals Charles R. Black Jr. and Roger Stone,[1][2][3] joined by Peter G. Kelly in 1984.[4] Manafort often lobbied on behalf of foreign leaders such as former President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych, former dictator of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos, former dictator of Zaire Mobutu Sese Seko, and Angolan guerrilla leader Jonas Savimbi.[5][6][7] Lobbying to serve the interests of foreign governments requires registration with the Justice Department under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA); on June 27, 2017, he retroactively registered as a foreign agent.[8][9][10][11]

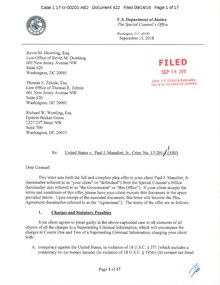

On October 27, 2017, Manafort and his business associate Rick Gates were indicted in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on multiple charges arising from his consulting work for the pro-Russian government of Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine before Yanukovych's overthrow in 2014.[12] The indictment came at the request of Robert Mueller's Special Counsel investigation.[13][14] In June 2018, additional charges were filed against Manafort for obstruction of justice and witness tampering that are alleged to have occurred while he was under house arrest,[15] and he was ordered to jail.[16]

Manafort was prosecuted in two federal courts. In August 2018, he stood trial in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia and was convicted on eight charges of tax and bank fraud. Manafort was next prosecuted on ten other charges, but this effort ended in a mistrial with Manafort later admitting his guilt.[17][18][19] In the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Manafort pled guilty to two charges of conspiracy to defraud the United States and witness tampering,[20] while agreeing to cooperate with prosecutors.

On November 26, 2018, Mueller reported that Manafort violated his plea deal by repeatedly lying to investigators. On February 13, 2019, D.C. District Court Judge Amy Berman Jackson concurred, voiding the plea deal.[21][22][23] On March 7, 2019, Judge T. S. Ellis III sentenced Manafort to 47 months in prison.[24][25][26] On March 13, 2019, Jackson sentenced Manafort to an additional 43 months in prison.[27][28][29] Minutes after his sentencing, New York state prosecutors charged Manafort with sixteen state felonies.[30] On December 18, 2019, the state charges against him were dismissed because of the doctrine of double jeopardy.[31][32][33] The Republican-controlled Senate Intelligence Committee concluded in August 2020 that Manafort's ties to individuals connected to Russian intelligence while he was Trump's campaign manager "represented a grave counterintelligence threat" by creating opportunities for "Russian intelligence services to exert influence over, and acquire confidential information on, the Trump campaign."[34]

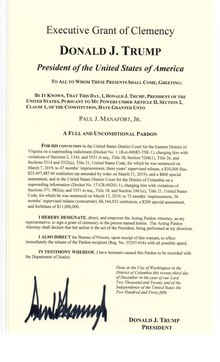

On May 13, 2020, Manafort was released to home confinement due to the threat of COVID-19.[35] On December 23, 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump pardoned Manafort.[36][37][38]

In mid-March 2024, Manafort re-emerged on the political scene, with reports of him potentially joining the Trump 2024 campaign.[39][40][41] His prospects with the Trump campaign may be complicated, however, by his business dealings in China since his release from prison.[42]

Early life and education

Paul John Manafort Jr. was born on April 1, 1949,[43] in New Britain, Connecticut. Manafort's parents are Antoinette Mary Manafort (née Cifalu; 1921–2003) and Paul John Manafort Sr. (1923–2013).[44][45] His grandfather immigrated to the United States from Italy in the early 20th century, settling in Connecticut.[46] He founded the construction company New Britain House Wrecking Company in 1919 (later renamed Manafort Brothers Inc.).[47] His father served in the U.S. Army combat engineers during World War II[45] and was mayor of New Britain from 1965 to 1971.[5] His father was indicted in a corruption scandal in 1981 but not convicted.[48]

In 1967, Manafort graduated from St. Thomas Aquinas High School, a private Roman Catholic secondary school, in New Britain.[49] He attended Georgetown University, where he received his B.S. in business administration in 1971 and his J.D. in 1974.[50][51]

Career

Between 1977 and 1980, Manafort practiced law with the firm of Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease in Washington, D.C.[43]

Political activities

In 1976, Manafort was the delegate-hunt coordinator for eight states for the President Ford Committee; the overall Ford delegate operation was run by James A. Baker III.[52] Between 1978 and 1980, Manafort was the southern coordinator for Ronald Reagan's presidential campaign, and the deputy political director at the Republican National Committee. After Reagan's election in November 1980, he was appointed associate director of the Presidential Personnel Office at the White House. In 1981, he was nominated to the board of directors of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.[43]

Manafort was an adviser to the presidential campaigns of George H. W. Bush in 1988[53] and Bob Dole in 1996.[54]

Chairman of Trump's 2016 campaign

In February 2016, Manafort approached Trump through a mutual friend, Thomas J. Barrack Jr. He pointed out his experience advising presidential campaigns in the United States and around the world, described himself as an outsider not connected to the Washington establishment, and offered to work without salary.[55] In March 2016, he joined Trump's presidential campaign to take the lead in getting commitments from convention delegates.[56] On June 20, 2016, Trump fired campaign manager Corey Lewandowski and promoted Manafort to the position. Manafort gained control of the daily operations of the campaign as well as an expanded $20 million budget, hiring decisions, advertising, and media strategy.[57][58][59]

On June 9, 2016, Manafort, Donald Trump Jr., and Jared Kushner were participants in a meeting with Russian attorney Natalia Veselnitskaya and several others at Trump Tower. A British music agent, saying he was acting on behalf of Emin Agalarov and the Russian government, had told Trump Jr. that he could obtain damaging information on Hillary Clinton if he met with a lawyer connected to the Kremlin.[60] At first, Trump Jr. said the meeting had been primarily about the Russian ban on international adoptions (in response to the Magnitsky Act) and mentioned nothing about Mrs. Clinton; he later said the offer of information about Clinton had been a pretext to conceal Veselnitskaya's real agenda.[61]

In August 2016, Manafort's connections to former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and his pro-Russian Party of Regions drew national attention in the US, where it was reported that Manafort may have received $12.7 million (~$15.8 million in 2023) in off-the-books funds from the Party of Regions.[62]

On August 17, 2016, Trump received his first security briefing.[63] The same day, August 17, Trump shook up his campaign organization in a way that appeared to minimize Manafort's role. It was reported that members of Trump's family, particularly Kushner, who had originally been a strong backer of Manafort, had become uneasy about his Russian connections and suspected that he had not been forthright about them.[64] Manafort stated in an internal staff memorandum that he would "remain the campaign chairman and chief strategist, providing the big-picture, long-range campaign vision".[65] However, two days later, Trump announced his acceptance of Manafort's resignation from the campaign after Steve Bannon and Kellyanne Conway took on senior leadership roles within that campaign.[66][67]

Upon Manafort's resignation as campaign chairman, Newt Gingrich stated, "nobody should underestimate how much Paul Manafort did to really help get this campaign to where it is right now."[68] Gingrich later added that, for the Trump administration, "It makes perfect sense for them to distance themselves from somebody who apparently didn't tell them what he was doing."[69]

In January 2019, Manafort's lawyers submitted a filing to the court in response to the allegation that Manafort had lied to investigators. Through an error in redacting, the document accidentally revealed that while he was campaign chairman, Manafort met with Konstantin Kilimnik, a likely Russian intelligence officer and an alleged operative of the "Mariupol Plan" which would separate eastern Ukraine by political means with Manafort's help.[70] The filing says Manafort gave him polling data related to the 2016 campaign and discussed a Ukrainian peace plan with him. Most of the polling data was reportedly public, although some was private Trump campaign polling data. Manafort asked Kilimnik to pass the data to Ukrainians Serhiy Lyovochkin and Rinat Akhmetov. The Republican-controlled Senate Intelligence Committee concluded in August 2020 that Manafort's contacts with Kilimnik and other affiliates of Russian intelligence "represented a grave counterintelligence threat" because his "presence on the Campaign and proximity to Trump created opportunities for Russian intelligence services to exert influence over, and acquire confidential information on, the Trump campaign."[71][72][34]

During a February 4, 2019, closed-door court hearing regarding false statements Manafort had made to investigators about his communications with Kilimnik, special counsel prosecutor Andrew Weissmann told judge Amy Berman Jackson that "This goes, I think, very much to the heart of what the special counsel's office is investigating," suggesting that Mueller's office continued to examine a possible agreement between Russia and the Trump campaign.[73]

While Manafort served within the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, it is alleged that Manafort, via Kyiv-based operative Konstantin Kilimnik, offered to provide briefings on political developments to Deripaska.[74][75] Behaviors such as these were seen by writers at The Atlantic as an attempt by Manafort "to please an oligarch tied to" Putin's government.[76]

Lobbying career

In 1980, Manafort was a founding partner of Washington, D.C.-based lobbying firm Black, Manafort & Stone, along with principals Charles R. Black Jr. and Roger Stone.[1][2][3][77] After Peter G. Kelly was recruited, the name of the firm was changed to Black, Manafort, Stone and Kelly (BMSK) in 1984.[4]: 124

Manafort left BMSK (then a subsidiary of Burson-Marsteller) in 1995 to join Richard H. Davis and Matthew C. Freedman in forming Davis, Manafort, and Freedman.[78]

Association with Jonas Savimbi

In 1985, Manafort's firm, BMSK, signed a $600,000 (~$1.44 million in 2023) contract with Jonas Savimbi, the leader of the Angolan rebel group UNITA, to refurbish Savimbi's image in Washington and secure financial support on the basis of his anti-communism stance. BMSK arranged for Savimbi to attend events at the American Enterprise Institute (where Jeane Kirkpatrick gave him a laudatory introduction), The Heritage Foundation, and Freedom House; in the wake of the campaign, Congress approved hundreds of millions of dollars in covert American aid to Savimbi's group.[79] Allegedly, Manafort's continuing lobbying efforts helped preserve the flow of money to Savimbi several years after the Soviet Union ceased its involvement in the Angolan conflict, forestalling peace talks.[79]

Lobbying for other foreign leaders

Between June 1984 and June 1986, Manafort was a FARA-registered lobbyist for Saudi Arabia. The Reagan Administration refused to grant Manafort a waiver from federal statutes prohibiting public officials from acting as foreign agents; Manafort resigned his directorship at OPIC in May 1986. An investigation by the Department of Justice found 18 lobbying-related activities that were not reported in FARA filings, including lobbying on behalf of The Bahamas and Saint Lucia.[80]

Manafort's firm, BMSK, accepted $950,000 yearly to lobby for then-president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos.[81][82] He was also involved in lobbying for Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaïre,[83] securing a US$1 million (~$2.14 million in 2023) annual contract in 1989,[84] and attempted to recruit Siad Barre of Somalia as a client.[85] His firm also lobbied on behalf of the governments of the Dominican Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya (earning between $660,000 and $750,000 each year between 1991 and 1993), and Nigeria ($1 million in 1991). These activities led Manafort's firm to be listed amongst the top five lobbying firms receiving money from human-rights abusing regimes in the Center for Public Integrity report "The Torturers' Lobby".[86]

The New York Times reported that Manafort accepted payment from the Kurdistan Region to facilitate Western recognition of the 2017 Kurdistan Region independence referendum.[87]

Involvement in the Karachi affair

Manafort wrote the campaign strategy for Édouard Balladur in the 1995 French elections, and was paid indirectly.[88] The money, at least $200,000, was transferred to him through his friend, Lebanese arms-dealer Abdul Rahman al-Assir, from middle-men fees paid for arranging the sale of three French Agosta-class submarines to Pakistan, in a scandal known as the Karachi affair.[79]

Association with Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence Agency

Manafort received $700,000 from the Kashmiri American Council between 1990 and 1994, supposedly to promote the plight of the Kashmiri people. However, an FBI investigation revealed the money was actually from Pakistan's Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) agency as part of a disinformation operation to divert attention from terrorism. A former Pakistani ISI official claimed Manafort was aware of the nature of the operation.[89] While producing a documentary as part of the deal, Manafort interviewed several Indian officials while pretending to be a CNN reporter.[90]

HUD scandal

In the late 1980s, Manafort was criticized for using his connections at HUD to ensure funding for a $43 million rehabilitation of dilapidated housing in Seabrook, New Jersey.[91] Manafort's firm received a $326,000 fee for its work in getting HUD approval of the grant, largely through personal influence with Deborah Gore Dean, an executive assistant to former HUD Secretary Samuel Pierce.[92]

Transition to Ukraine

Manafort's involvement in Ukraine can be traced to 2003, when Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska hired Dole, Manafort's prior campaign candidate, to lobby the State Department for a waiver of his visa ban, primarily so that he could solicit otherwise unavailable institutional purchasers for shares in his company, RusAL.[93][94] Then in early 2004, Deripaska met with Manafort's partner, Rick Davis, also a prior campaign adviser to Bob Dole, to discuss hiring Manafort and Davis to return the former Georgian Minister of State Security, Igor Giorgadze, to prominence in Georgian politics.[95]

By December 2004, however, Deripaska shelved his plans in Georgia and dispatched Manafort to meet with Akhmetov in Ukraine to help Akhmetov and his holding firm, System Capital Management, weather the political crisis brought by the Orange Revolution.[95] Akhmetov would eventually flee to Monaco after being accused of murder, but during the crisis Manafort shepherded Akhemtov around Washington, meeting with U.S. officials like Dick Cheney.[93][94][95] Akhmetov introduced Manafort to Yanukovych, to whose political party, the Party of Regions, Akhmetov was a contributor.[96]

Lobbying for Viktor Yanukovych and involvements in Ukraine

Manafort worked as an adviser on the Ukrainian presidential campaign of Yanukovych (and his Party of Regions during the same time span) from December 2004 until the February 2010 Ukrainian presidential election,[96][97][98] even as the U.S. government (and U.S. Senator John McCain) opposed Yanukovych because of his ties to Russia's leader Vladimir Putin.[54] Manafort was hired to advise Yanukovych months after massive street demonstrations known as the Orange Revolution overturned rigged Yanukovych's victory in the 2004 presidential race.[99] Borys Kolesnikov, Yanukovych's campaign manager, said the party hired Manafort after identifying organizational and other problems in the 2004 elections, in which it was advised by Russian strategists.[98] Manafort rebuffed U.S. Ambassador William B. Taylor Jr. when the latter complained he was undermining U.S. interests in Ukraine.[79] According to a 2008 U.S. Justice Department annual report, Manafort's company received $63,750 from Yanukovych's Party of Regions over a six-month period ending on March 31, 2008, for consulting services.[100] In the 2010 election, Yanukovych managed to pull off a narrow win over Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, a leader of the 2004 demonstrations. Yanukovych owed his comeback in Ukraine's presidential election to a drastic makeover of his political persona, and—people in his party say—that makeover was engineered in part by his American consultant, Manafort.[98]

In 2007 and 2008, Manafort was involved in investment projects with Deripaska—the acquisition of a Ukrainian telecommunications company—and Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash—redevelopment of the site of the former Drake Hotel in New York City).[101] Manafort negotiated a $10 million (~$15 million in 2023) annual contract with Deripaska to promote Russian interests in politics, business, and media coverage in Europe and the United States, starting in 2005.[102] A witness at Manafort's 2018 trial for fraud and tax evasion testified that Deripaska loaned Manafort $10 million in 2010, which to her knowledge was never repaid.[48]

At Manafort's trial, federal prosecutors alleged that between 2010 and 2014 he was paid more than $60 million by Ukrainian sponsors, including Akhmetov, believed to be the richest man in Ukraine.[48]

In May 2011, Yanukovych stated that he would strive for Ukraine to join the European Union,[103] In 2013, Yanukovych became the main target of the Euromaidan protests.[104] After the February 2014 Ukrainian revolution (the conclusion of Euromaidan), Yanukovych fled to Russia.[104][105] On March 17, 2014, the day after the Crimean status referendum, Yanukovych became one of the first eleven persons who were placed under executive sanctions on the Specially Designated Nationals List (SDN) by President Barack Obama, freezing his assets in the US and banning him from entering the United States.[106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][a]

Manafort then returned to Ukraine in September 2014 to become an adviser to Yanukovych's former head of the Presidential Administration of Ukraine Serhiy Lyovochkin.[96] In this role, he was asked to assist in rebranding Yanukovych's Party of Regions.[96] Instead, he argued to help stabilize Ukraine. Manafort was instrumental in creating a new political party called Opposition Bloc.[96] According to Ukrainian political analyst Mikhail Pogrebinsky, "He thought to gather the largest number of people opposed to the current government, you needed to avoid anything concrete, and just become a symbol of being opposed".[96] According to Manafort, he has not worked in Ukraine since the October 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election.[117][118] However, according to Ukrainian border control entry data, Manafort traveled to Ukraine several times after that election, all the way through late 2015.[118] According to The New York Times, his local office in Ukraine closed in May 2016.[62] According to Politico, by then Opposition Bloc had already stopped payments for Manafort and this local office.[118]

In an April 2016 interview with ABC News, Manafort stated that the aim of his activities in Ukraine had been to lead the country "closer to Europe".[119]

Ukrainian government National Anti-Corruption Bureau studying secret documents claimed in August 2016 to have found handwritten records that show $12.7 million in cash payments designated for Manafort, although they had yet to determine if he had received the money.[62] These undisclosed payments were from the pro-Russian political party Party of Regions, of the former president of Ukraine Yanukovych.[62] This payment record spans from 2007 to 2012.[62] Manafort's lawyer, Richard A. Hibey, said Manafort didn't receive "any such cash payments" as described by the anti-corruption officials.[62] The Associated Press reported on August 17, 2016, that Manafort secretly routed at least $2.2 million in payments to two prominent Washington lobbying firms in 2012 on Party of Regions' behalf, and did so in a way that effectively obscured the foreign political party's efforts to influence U.S. policy.[10] Associated Press noted that under federal law, U.S. lobbyists must declare publicly if they represent foreign leaders or their political parties and provide detailed reports about their actions to the Justice Department, which Manafort reportedly did not do.[10] The lobbying firms unsuccessfully lobbied U.S. Congress to reject a resolution condemning the jailing of Yanukovych's main political rival, Yulia Tymoshenko.[120]

Financial records certified in December 2015 and filed by Manafort in Cyprus showed him to be approximately $17 million (~$21.4 million in 2023) in debt to interests connected to interests favorable to Putin and Yanukovych in the months before joining the Trump presidential campaign in March.[121] These included a $7.8 million debt to Oguster Management Limited, a company connected to Deripaska.[121] This accords with a 2015 court complaint filed by Deripaska claiming that Manafort and his partners owed him $19 million in relation to a failed Ukrainian cable television business.[121] In January 2018, Surf Horizon Limited, a Cyprus-based company tied to Deripaska, sued Manafort and his business partner Richard "Rick" Gates, accusing them of financial fraud by misappropriating more than $18.9 million that the company had invested in Ukrainian telecom companies, known collectively as the "Black Sea Cable".[122] An additional $9.9 million debt was owed to a Cyprus company that tied through shell companies to Ivan Fursin, a Ukrainian Member of Parliament of the Party of Regions.[121] Manafort spokesman Jason Maloni maintained in response, "Manafort is not indebted to Deripaska or the Party of Regions, nor was he at the time he began working for the Trump campaign."[121] During the 2016 Presidential campaign, Manafort, via Kilimnik, offered to provide briefings on political developments to Deripaska, though there is no evidence that the briefings took place.[74][123] A July 2017 application by the FBI for a search warrant revealed that a company controlled by Manafort and his wife had received a $10 million (~$12.2 million in 2023) loan from Deripaska.[124][125]

According to leaked text messages between his daughters, Manafort was also one of the proponents of violent removal of the Euromaidan protesters, which resulted in police shooting dozens of people during 2014 Hrushevskoho Street riots. In one of the messages, his daughter writes that it was his "strategy that was to cause that, to send those people out and get them slaughtered."[126]

Manafort has rejected questions about whether Kilimnik, with whom he consulted regularly, might be in league with Russian intelligence.[127] According to Yuri Shvets, Kilimnik previously worked for the GRU, and every bit of information about his work with Manafort went directly to Russian intelligence.[128]

2017 activities

Registering as a foreign agent

Lobbying for foreign countries requires registration with the Justice Department under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). Manafort did not do so at the time of his lobbying. In April 2017, a Manafort spokesman said Manafort was planning to file the required paperwork; however, according to Associated Press reporters, as of June 2, 2017, Manafort had not yet registered.[8][10] On June 27, he filed to be retroactively registered as a foreign agent.[11] Among other things, he disclosed that he made more than $17 million between 2012 and 2014 working for a pro-Russian political party in Ukraine.[129][130] The sentencing memorandum submitted by the Office of Special Council on February 23, 2019, stated that the "filing was plainly deficient. Manafort entirely omitted [his] United States lobbying contracts ... and a portion of the substantial compensation Manafort received from Ukraine."[131]

China, Puerto Rico, and Ecuador

Early in 2017, Manafort supported Chinese efforts at providing development and investment worldwide and in Puerto Rico and Ecuador.[132] Early in 2017, he discussed possible Chinese investment sources for Ecuador with Lenín Moreno who later obtained loans worth several billion US dollars from the China Development Bank.[132] In May 2017, Manafort and Moreno discussed the possibility of Manafort brokering a deal for Ecuador to relinquish Julian Assange to American authorities in exchange for concessions such as debt relief from the United States.[133]

Manafort acted as the go between for the China Development Bank's investment fund to support bailout bonds for Puerto Rico's sovereign debt financing and other infrastructure items.[132] Also, he advised a Shanghai construction billionaire Yan Jiehe (严介和), who owns the Pacific Construction Group (太平洋建设) and is China's seventh richest man with a fortune estimated at $14.2 billion in 2015, on obtaining international contracts.[132][134][135]

Kurdish independence referendum

In mid-2017, Manafort left the United States in order to help organize the 2017 Kurdistan Region independence referendum that was to be held on September 25, 2017, something that surprised both investigators and the media.[136] He was hired by the President of Kurdistan Region Masoud Barzani's son Masrour Barzani who heads the Kurdistan Region Security Council.[132][137] To help Manafort's efforts in supporting Kurdish freedom and independence, his longtime associate Phillip M. Griffin traveled to Erbil prior to the vote.[132] The referendum was not supported by United States Secretary of Defense James Mattis.[138] Manafort returned to the United States just before both his indictment and the start of the 2017 Iraqi–Kurdish conflict in which the Peshmerga-led Kurds lost the Mosul Dam and their main revenue source at the Baba GurGur Kirkuk oilfields to Iraqi forces.[139][140]

Homes, home loans and other loans

Manafort's work in Ukraine coincided with the purchase of at least four prime pieces of real estate in the United States, worth a combined $11 million, between 2006 and early 2012.[141] In 2006, Manafort purchased an apartment on the 43rd floor of Trump Tower for a reported $3.6 million (~$5.24 million in 2023).[142] Manafort, however, purchased the unit indirectly, through an LLC named after him and his partner Rick Hannah Davis, "John Hannah, LLC."[143] That LLC, according to court documents in Manafort's indictment, came into existence in April 2006,[144] roughly one month after the Ukrainian parliamentary elections that saw Manafort help bring Yanukovych back to power on March 22, 2006.[145] According to Afghan-Ukrainian journalist Mustafa Nayyem, Akhmetov, the Ukrainian oligarch sponsoring Yanukovych, paid the $3 million purchase price for Manafort's Trump Tower apartment for helping win the election.[93] It was not until March 5, 2015, when Manafort's income from Ukraine dwindled,[146] that Manafort would transfer the property out of John Hannah, LLC, and into his own personal name so that he could take out a $3 million loan against the property.[147] The Trump Tower residence was claimed as Manafort's primary residence in order to receive a tax abatement, though Manafort also listed a Florida residence as his primary residence, also to gain tax breaks.[148] The property was since seized by the federal government, and listed for sale in 2019.[149]

Since 2012, Manafort has taken out seven home equity loans worth approximately $19.2 million (~$25.2 million in 2023) on three separate New York-area properties he owns through holding companies registered to him and his then son-in-law Jeffrey Yohai, a real estate investor.[150] In 2016, Yohai declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy for LLCs tied to four residential properties held with the actor Jake Hoffman; Manafort holds a $2.7 million (~$3.36 million in 2023) claim on one of the properties.[151]

As of February 2017, Manafort had about $12 million in home equity loans outstanding. For one home, loans of $6.6 million exceeded the value of that home; the loans are from the Federal Savings Bank of Chicago, Illinois, whose CEO, Stephen Calk, was a campaign supporter of Donald Trump and was a member of Trump's economic advisory council during the campaign.[150] In July 2017, New York prosecutors subpoenaed information about the loans issued to Manafort during the 2016 presidential campaign. At the time, these loans represented about a quarter of the bank's equity capital.[152]

The Mueller investigation is reviewing a number of loans that Manafort has received since leaving the Trump campaign in August 2016, specifically $7 million (~$8.71 million in 2023) from Oguster Management Limited, a British Virgin Islands-registered company connected to Deripaska, to another Manafort-linked company, Cyprus-registered LOAV Advisers Ltd.[153] This entire amount was unsecured, carried interest at 2%, and had no repayment date. Additionally, NBC News found documents that reveal loans of more than $27 million from the two Cyprus entities to a third company connected to Manafort, a limited-liability corporation registered in Delaware. This company, Jesand LLC, bears a strong resemblance to the names of Manafort's daughters, Jessica and Andrea.[154]

Russia investigations

FBI and Special Counsel investigation

The FBI reportedly began a criminal investigation into Manafort in 2014, shortly after Yanukovych was deposed during Euromaidan.[155] That investigation predated the 2016 election by several years and is ongoing. In addition, Manafort is also a person of interest in the FBI counterintelligence probe looking into the Russian government's interference in the 2016 presidential election.[8]

On January 19, 2017, the eve of Trump's presidential inauguration, it was reported that Manafort was under active investigation by multiple federal agencies including the Central Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Director of National Intelligence, and the financial crimes unit of the Treasury Department.[156] Investigations were said to be based on intercepted Russian communications as well as financial transactions.[157] CNN reported in September 2017 that Manafort was wiretapped by the FBI "before and after the election ... including a period when Manafort was known to talk to President Donald Trump." The surveillance of Manafort reportedly began in 2014, before Donald Trump announced his candidacy for President of United States. According to a subsequent CNN editor's note, however: "On December 9, 2019, the Justice Department Inspector General released a report regarding the opening of the investigation on Russian election interference and Donald Trump's campaign. In the report, the IG contradicts what CNN was told in 2017, noting that the FBI team overseeing the investigation did not seek FISA surveillance of Paul Manafort".[158][159]: 357 [160]

Special Counsel Robert Mueller, who was appointed on May 17, 2017, by the Justice Department to oversee the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections and related matters, took over the existing criminal probe involving Manafort.[8][161] On July 26, 2017, the day after Manafort's United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence hearing and the morning of his planned hearing before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, FBI agents at Mueller's direction conducted a raid on Manafort's Alexandria, Virginia home, using a search warrant to seize documents and other materials, in regard to the Russian meddling in the 2016 election.[162][163] Initial press reports indicated Mueller obtained a no-knock warrant for this raid, though Mueller's office has disputed these reports in court documents.[164][165] United States v. Paul Manafort was analyzed by attorney George T. Conway III, who wrote that it strengthened the constitutionality of the Mueller investigation.[166]

Former Trump attorney John Dowd denied March 2018 reports by The New York Times and The Washington Post that in 2017 he had broached the idea of a presidential pardon for Manafort with his attorneys.[167][168]

Congressional investigations

In May 2017, in response to a request of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI), Manafort submitted over "300 pages of documents ... included drafts of speeches, calendars and notes from his time on the campaign" to the Committee "related to its investigation of Russian election meddling."[169] On July 25, he met privately with the committee.[170]

A congressional hearing on Russia issues, including the Trump campaign-Russian meeting, was scheduled by the Senate Committee on the Judiciary for July 26, 2017. Manafort was scheduled to appear together with Trump Jr., while Kushner was to testify in a separate closed session.[171] After separate negotiations, both Manafort and Trump Jr. met with the committee on July 26 in closed session and agreed to turn over requested documents. They are expected to testify in public eventually.[172]

The United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence concluded in its August 2020 final report that as Trump campaign manager "Manafort worked with Kilimnik starting in 2016 on narratives that sought to undermine evidence that Russia interfered in the 2016 U.S. election" and to direct such suspicions toward Ukraine. The report characterized Kilimnik as a "Russian intelligence officer" and said Manafort's activities represented a "grave counterintelligence threat."[173] The investigation found:

Manafort's presence on the Campaign and proximity to Trump created opportunities for the Russian intelligence services to exert influence over, and acquire confidential information on, the Trump Campaign. The Committee assesses that Kilimnik likely served as a channel to Manafort for Russian intelligence services, and that those services likely sought to exploit Manafort's access to gain insight [into] the Campaign...On numerous occasions over the course of his time of the Trump Campaign, Manafort sought to secretly share internal campaign information with Kilimnik...Manafort briefed Kilimnik on sensitive campaign polling data and the campaign's strategy for beating Hillary Clinton.[174][175]

The Committee did not definitively establish Kilimnik as a channel connected to the hacking and leaking of DNC emails, noting that its investigation was hampered by Manafort and Kilimnik's use of "sophisticated communications security practices" and Manafort's lies during SCO interviews on the topic.[176] The report noted: "Manafort's obfuscation of the truth surrounding Kilimnik was particularly damaging to the Committee's investigation because it effectively foreclosed direct insight into a series of interactions and communications which represent the single most direct tie between senior Trump Campaign officials and the Russian intelligence services."[176] In April 2021, a document released by the U.S. Treasury Department announcing new sanctions against Russia confirmed a direct pipeline from Manafort to Russian intelligence, noting: “During the 2016 U.S. presidential election campaign, Kilimnik provided the Russian Intelligence Services with sensitive information on polling and campaign strategy”.[177][178]

The fifth and final volume of the August 2020 Senate Intelligence Committee report, in a section on Manafort, noted: "Manafort had direct access to Trump" as well as the Trump campaign's senior officials, strategies, and information," and "Manafort, often with the assistance of Gates, engaged with individuals inside Russia and Ukraine on matters pertaining both to his personal business prospects and the 2016 U.S. election."[179][180] The report found that beginning around 2004, Manafort began to work for Deripaska and pro-Russian oligarchs in Ukraine, and that this involvement led to Manafort's involvement in the victory of Yanukovych in the 2010 Ukrainian elections.[179][180] The committee report stated: "The Russian government coordinates with and directs Deripaska" as part of the influence operations that Manafort assisted with, and that "Manafort's influence work for Deripaska was, in effect, influence work for the Russian government and its interests."[179][180]

Private investigation

The Trump–Russia dossier, also known as the Steele dossier,[181] is a private intelligence report comprising investigation memos written between June and December 2016 by Christopher Steele.[182] Manafort is a major figure mentioned in the Steele dossier, where allegations are made about Manafort's relationships and actions toward the Trump campaign, Russia, Ukraine, and Viktor Yanukovych. The dossier claims:

- that "the Republican candidate's campaign manager, Paul MANAFORT" had "managed" the "well-developed conspiracy of co-operation between [the Trump campaign] and the Russian leadership," and that he used "foreign policy adviser, Carter PAGE, and others as intermediaries."[183][184][185][186] (Dossier, p. 7)

- that Yanukovych told Putin he had been making untraceable[187] "kick-back payments" to Manafort, who was Trump's campaign manager at the time.[188] (Dossier, p. 20)

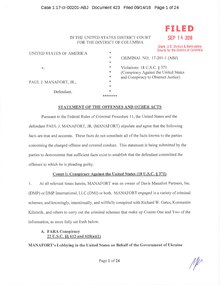

Indictments and charges

On October 30, 2017, Manafort was arrested by the FBI after being indicted by a federal grand jury as part of Mueller's investigation into the Trump campaign.[189][190] The indictment against Manafort and Rick Gates charged them with engaging in a conspiracy against the United States,[14][191] engaging in a conspiracy to launder money,[14][191] failing to file reports of foreign bank and financial accounts,[14][191][b] acting as an unregistered agent of a foreign principal,[14][191] making false and misleading statements in documents filed and submitted under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA),[14][191] and making false statements.[14][191] Prosecutors claimed Manafort laundered more than $18 million (equivalent to $22,374,152 in 2023), money he had received as compensation for lobbying and consulting services for Yanukovych.[191][198]

Manafort and Gates pleaded not guilty to the charges at their court appearance on October 30, 2017.[199][200] The US government asked the court to set Manafort's bail at $10 million and Gates at $5 million.[200] The court placed Manafort and Gates under house arrest after prosecutors described them as flight risks.[201] If convicted on all charges, Manafort could face decades in prison.[202][203]

Following the hearing, Manafort's attorney Kevin M. Downing made a public statement to the press proclaiming his client's innocence while describing the federal charges stemming from the indictment as "ridiculous".[204] Downing defended Manafort's decade-long lobbying effort for Yanukovych, describing their lucrative partnership as attempts to spread democracy and strengthen the relationship between the United States and Ukraine.[205] Judge Stewart responded by threatening to impose a gag order, saying "I expect counsel to do their talking in this courtroom and in their pleadings and not on the courthouse steps."[206] Revealed on September 13, 2018, Manafort and Donald Trump had signed a joint defense agreement allowing their attorneys to share information during the Mueller investigations and, previously, joint defense agreements had been arranged between Donald Trump and both Michael Cohen and Michael Flynn.[207][208]

On November 30, 2017, Manafort's attorneys said that Manafort had reached a bail agreement with prosecutors that would free him from the house arrest he had been under since his indictment. He offered bail in the form of $11.65 million worth of real estate.[209] While out on bond, Paul Manafort worked on an op-ed with a "Russian who has ties to the Russian intelligence service", prosecutors said in a court filing[210] requesting that the judge in the case revoke Manafort's bond agreement.[211]

On January 3, 2018, Manafort filed a lawsuit challenging Mueller's broad authority and alleging the Justice Department violated the law in appointing Mueller.[212] A spokesperson for the department replied that "The lawsuit is frivolous but the defendant is entitled to file whatever he wants".[212]

On February 2, 2018, the Department of Justice filed a motion seeking to dismiss the civil suit Manafort brought against Mueller.[213] Judge Jackson dismissed the suit on April 27, 2018, citing precedent that a court should not use civil powers to interfere in an ongoing criminal case. She did not, however, make any judgment as to the merits of the arguments presented.[214]

On February 22, 2018, both Manafort and Gates were further charged with additional crimes involving a tax avoidance scheme and bank fraud in Virginia.[215][216] The charges were filed in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, rather than in the District of Columbia, as the alleged tax fraud overt actions had occurred in Virginia and not in the District.[217] The new indictment alleged that Manafort, with assistance from Gates, laundered over $30 million through offshore bank accounts between approximately 2006 and 2015. Manafort allegedly used funds in these offshore accounts to purchase real estate in the United States, in addition to personal goods and services.[217]

On February 23, 2018, Gates pleaded guilty in federal court to lying to investigators and engaging in a conspiracy to defraud the United States.[218] Through a spokesman, Manafort expressed disappointment in Gates' decision to plead guilty and said he had no similar plans. "I continue to maintain my innocence," he said.[219]

On February 28, 2018, Manafort entered a not guilty plea in the District Court for the District of Columbia. Jackson subsequently set a trial date of September 17, 2018, and reprimanded Manafort and his attorney for violating her gag order by issuing a statement the previous week after former co-defendant Gates pleaded guilty. Manafort commented, "I had hoped and expected my business colleague would have had the strength to continue the battle to prove our innocence."[220]

On March 8, 2018, Manafort also pleaded not guilty to bank fraud and tax charges in federal court in Alexandria, Virginia. Judge T. S. Ellis III of the Eastern District of Virginia set his trial on those charges to begin on July 10, 2018.[221] He later pushed the trial back to July 24, citing a medical procedure involving a member of Ellis's family.[222] Ellis also expressed concern that the special counsel and Mueller were only interested in charging Manafort to squeeze him for information that would reflect on Mr. Trump or lead to Trump's impeachment.[223] Ellis later retracted his comments against the Mueller prosecution.[224][225]

Friends of Manafort announced the establishment of a legal defense fund on May 30, 2018, to help pay his legal bills.[226]

On June 8, 2018, Manafort and Kilimnik were indicted for obstruction of justice and witness tampering.[227] The charges involved allegations that Manafort had attempted to convince others to lie about an undisclosed lobbying effort on behalf of Ukraine's former pro-Russian government. Since this allegedly occurred while Manafort was under house arrest, Judge Jackson revoked Manafort's bail on June 15 and ordered him held in jail until his trial.[228] Manafort was booked into the Northern Neck Regional Jail in Warsaw, Virginia, at 8:22 PM on June 15, 2018, where he was housed in the VIP section and kept in solitary confinement for his own safety.[229][230][231][232] On June 22, Manafort's efforts to have the money laundering charges against him dismissed were rejected by the court.[233][234] Citing Alexandria's D.C. suburbia status, abundant and significantly negative press coverage, and the margin by which Hillary Clinton won the Alexandria Division in the 2016 presidential election, Manafort moved the court for a change of venue to Roanoke, Virginia on July 6, 2018, citing Constitution entitlement to a fair and unbiased trial.[235][236] On July 10, Judge T. S. Ellis ordered Manafort to be transferred back to the Alexandria Detention Center, an order Manafort opposed.[237][238]

In February 2023, Manafort agreed to pay $3.15 million to settle a civil suit brought by the Justice Department in 2022 regarding undisclosed foreign bank accounts.[239]

New York State indictment

On March 13, 2019, the same day on which he was sentenced in the Washington case, Manafort was indicted by the Manhattan District Attorney on 16 charges related to mortgage fraud. District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. said the charges stemmed from an investigation launched in March 2017.[240] Unlike his previous convictions, these were levied by the State of New York, and therefore a presidential pardon cannot override or affect the sentence in the event of conviction.[30] NBC News reported in August 2017 that a state investigator was exploring jurisdiction to charge potential defendants in the Mueller probe with state crimes, and that such charges could provide an end run around any presidential pardons.[241] On December 18, 2019, Justice Maxwell Wiley of the New York Supreme Court, Criminal Term, New York County, dismissed the charges against Manafort.[31][32][33]

On August 20, 2020, the New York County District Attorney's Office appealed the dismissal to the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division.[242][243] In October 2020, a panel of the Appellate Division unanimously upheld the dismissal.[244][245] After Manafort was pardoned in December 2020, the Manhattan District Attorney's Office announced it would continue to seek appellate remedies.[246] On February 4, 2021, the New York Court of Appeals declined to hear the appeal of the Appellate Division's decision.[247][248]

Trials

The numerous indictments against Manafort were divided into two trials.

Eastern District of Virginia

Manafort was tried in the Eastern District of Virginia on eighteen charges including tax evasion, bank fraud, and hiding foreign bank accounts - financial crimes uncovered during the special counsel's investigation into Russia's role in the 2016 election.[18] The trial began on July 31, 2018, before U.S. District Judge T. S. Ellis III.[249][250] On August 21, the jury found Manafort guilty on eight of the eighteen charges, while Ellis declared a mistrial on the other ten.[18] He was convicted on five counts of tax fraud, one of the four counts of failing to disclose his foreign bank accounts, and two counts of bank fraud.[251] The jury was hung on three of the four counts of failing to disclose, as well as five counts of bank fraud, four of them related to the Federal Savings Bank of Chicago run by Stephen Calk.[252] Mueller's office advised the court that Manafort should receive a sentence of 20 to 24 years,[253] a sentence consistent with federal guidelines, but on March 7, 2019, Ellis sentenced Manafort to just 47 months in prison, less nine months for time already served, adding that the recommended sentence was "excessive" and that Manafort had lived an "otherwise blameless life." However, Ellis noted that Manafort had not expressed "regret for engaging in wrongful conduct".[254][255][256]

District of Columbia

Manafort's trial in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia was scheduled to begin in September 2018.[220] He was charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States, money laundering, failing to register as a foreign lobbyist, making false statements to investigators, and witness tampering.[257] On September 14, 2018, Manafort entered into a plea deal with prosecutors and pleaded guilty to two charges: conspiracy to defraud the United States and witness tampering.[258] He also agreed to forfeit to the government cash and property worth an estimated $11-$26 million,[259] and to co-operate fully with the Special Counsel.[260] A tentative sentencing date for Manafort's guilty plea in the D.C. case has been set for March 2019.[261]

Mueller's office stated in a November 26, 2018, court filing that Manafort had repeatedly lied to prosecutors about a variety of matters, breaching the terms of his plea agreement. Manafort's attorneys disputed the assertion.[262] On December 7, 2018, the special counsel's office filed a document with the court listing five areas in which they say Manafort lied to them, which they said negated the plea agreement.[261] DC District Court judge Amy Berman Jackson ruled on February 13, 2019, that Manafort had violated his plea deal by repeatedly lying to prosecutors.[263]

In a February 7, 2019, hearing before U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Judge Amy Berman Jackson, prosecutors speculated that Manafort had concealed facts about his activities to enhance the possibility of his receiving a pardon. They said that Manafort's work with Ukraine had continued after he had made his plea deal and that during the Trump campaign, he met with his campaign deputy Rick Gates, who also had pleaded guilty in the case, and with alleged Russian Federation intelligence agent, Konstantin Kilimnik, in an exclusive New York cigar bar. Gates said the three left the premises separately, each using different exits.[264]

On March 13, 2019, Jackson sentenced Manafort to 73 months in prison, with 30 months concurrent with the jail time he received in the Virginia case, for a resultant sentence of an additional 43 months in jail (30 additional months for conspiracy to defraud the United States and 13 additional months for witness tampering). Manafort also apologized for his actions.[28][29][265]

Prison sentence

Manafort was jailed from June 2018 until May 2020. During that time he was briefly held at the United States Penitentiary Canaan in Waymart, Pennsylvania. He was held at Federal Correctional Institution, Loretto in Loretto, Pennsylvania (inmate #35207-016).[266] In June 2019, he was moved to the Metropolitan Correctional Center, New York in Manhattan.[267] In August 2019, he was moved back to the Federal Correctional Institution, Lorretto, Pennsylvania with an expected release date of December 25, 2024.[267] On May 13, 2020, Manafort was released to home confinement over COVID-19 concerns.[268] On December 23, 2020, Trump issued Manafort a full pardon.[269]

As part of his pardon, some of his forfeitures were unwound. He was able to retain his large house in Water Mill, New York, his brownstone in Brooklyn, his apartment on the edge of Manhattan’s Chinatown, and assets seized in an account at Federal Savings Bank. He did not retain assets that were already forfeited and sold, such as an apartment in Trump Tower in Manhattan, a bank account and a life insurance policy.[270]

Law licenses

In 2017, Massachusetts lawyer J. Whitfield Larrabee filed a misconduct complaint against Manafort in the Connecticut Statewide Grievance Committee, seeking his disbarment on the basis of "conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit and misrepresentation."[271] In 2018, after Manafort pleaded guilty to conspiracy, the Connecticut Office of Chief Disciplinary Counsel brought a case against Manafort.[272] In January 2019, ahead of a disbarment hearing, Manafort resigned from the Connecticut bar and waived his right to ever seek readmission.[273][274][275]

Manafort was disbarred from the DC Bar on May 9, 2019.[276]

Personal life

Manafort has been married to Kathleen Bond Manafort since August 12, 1978; she graduated from George Washington University with a B.B.A. in 1979, became an attorney after graduating from Georgetown University Law Center with a J.D. and passing her Virginia Bar exam in 1988, and became a member of the DC Bar in 1991.[277] They have two adult daughters, Jessica and Andrea.[126]

See also:

- Links between Trump associates and Russian officials and spies

- Carter Page

- Conspiracy theories related to the Trump–Ukraine scandal

- List of people pardoned or granted clemency by the president of the United States

- Timeline of Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections

- Timeline of investigations into Trump and Russia (2017)

- Timeline of investigations into Trump and Russia (January–June 2018)

- Timeline of investigations into Trump and Russia (July–December 2018)

- Timeline of investigations into Trump and Russia (2019)

Further reading

- Foer, Franklin (March 2018). "The Plot Against America". The Atlantic.

External links

https://www.nytimes.com/…/politi…/manafort-trump-trial.html…

"What's Past is Prologue..."

[NOTE: The following article was originally posted on August 12, 2018]

https://www.nytimes.com/…/politi…/manafort-trump-trial.html…

ALEXANDRIA, Va. — A week before the Trump presidential campaign announced that it had hired Paul Manafort, a Yankees ticket specialist alerted him that his annual season tickets would soon be arriving at his 43rd-floor apartment at Trump Tower in New York.

“Will you and Kathy be attending opening day?” the specialist asked in an email in late March 2016, referring to Mr. Manafort’s wife. “Yes, Kathy and I will be attending,” Mr. Manafort replied. The four seats — prime spots behind the Yankees’ dugout, with access to the owner’s suite — cost $210,600 for the season.

But Mr. Manafort didn’t have the money to pay for them. Six months later, he still had not paid the American Express bill that included the charge.

He didn’t have money to make payments on the $5.3 million loan he had just taken out against his Brooklyn brownstone, either, which was heading toward foreclosure as he ran the Trump campaign. His political consulting firm was at least $600,000 in debt and had not had a single client after taking in more than $60 million in five years from the Ukrainian oligarchs funding the country’s pro-Russia president.

The whole trajectory of Mr. Manafort’s life — from the son of a blue-collar, small-town mayor to a jet-setting international political consultant to Trump campaign chairman and now to prisoner in an Alexandria, Va., jail awaiting a jury verdict — is a tale of greed, deception and ego. His trial on 18 charges of bank and tax fraud has ripped away the elaborate facade of a man who, the story went, had moved the swimming pool at one of his eight homes a few feet to catch the perfect combination of sun and shade, and who worked for the Trump campaign at no charge to intimate that for a man of his fabulous wealth, a salary was trivial.

His trial also underscores questions about how someone in such deep financial trouble rose to the top of the Trump campaign, spreading a stain that has touched the president’s innermost circle. The formidable parade of more than 20 witnesses and hundreds of exhibits has further eroded the notion, advanced by President Trump, that the special counsel investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election, Robert S. Mueller III, is on a “witch hunt.”

The trial is also a spectacle of small humiliations for Mr. Manafort, 69. His once perfectly coifed dark hair, admired by Mr. Trump, is now gray and shaggy without the benefit of a stylist. His shirts, which he once bought by the half dozen for $1,500 each, are now delivered by his wife to his lawyer in a white plastic bag. Their communication consists of him winking at her or forming a silent kiss as he is led in and out of the courtroom. He has been admonished not to turn around in his courtroom seat to look at her.

A subplot of the saga is the betrayal of Mr. Manafort by his longtime deputy Rick Gates, who had been at his side for the last dozen years. A former senior official of both the Trump campaign and the Trump inaugural committee, Mr. Gates has testified that he helped execute Mr. Manafort’s fraudulent schemes while simultaneously stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from him, apparently because he felt that Mr. Manafort was not dividing the riches from Ukraine fairly.

Mr. Gates, 46, has pleaded guilty to two felony charges and is hoping that by helping Mr. Mueller prosecute Mr. Manafort, he might receive probation despite the long list of additional crimes with which he has been charged. On the witness stand Tuesday, he sneaked a furtive glance at Mr. Manafort at a moment when his former boss was looking at his notes. In testimony, he stated that he had decided to come clean, but that Mr. Manafort had decided otherwise.

Some of Mr. Manafort’s associates now say they had predicted that greed would be his downfall. Blessed with extraordinary political instincts and his Georgetown Law School degree, Mr. Manafort built his political consultancy into a power center in Reagan-era Washington, where the name of Black, Manafort and Stone became synonymous with string-pulling, insider access and electoral success.

But along the way, many say, he became a mercenary, willing to serve brutal dictators and corrupt industrialists as long as they paid handsomely. Riva Levinson, an international lobbyist who worked for Mr. Manafort from 1985 to 1995, said she initially accepted his explanation that he served strongmen to push them closer to Western democratic ideals. But “as time went on,” she said in an interview, “it seemed to me, he became all about money, big money.”

The Russia-aligned oligarchs backing Viktor F. Yanukovych, the Ukrainian president whose rise to power Mr. Manafort helped stage-manage, provided very big money for at least five years. But when a popular uprising forced Mr. Yanukovych from power in 2014 and that financial spigot shut off, the government claims, Mr. Manafort resorted to bank fraud rather than give up his lifestyle.

Paul John Manafort Jr. was born in New Britain, Conn., about 12 miles from Hartford. He caught the political bug from his father, the town’s mayor, when P.J., as Paul was then known, was in high school. His father was indicted over accusations of perjury in a municipal corruption scandal in 1981 but never convicted.

As an undergraduate and then a law student at Georgetown University, Mr. Manafort gravitated toward Republican politics. By the time he married Kathleen Bond, a George Washington University graduate, in 1978, he had already worked on Gerald Ford’s presidential campaign, and he would soon be hired by Ronald Reagan’s.

Tall, good-looking, with an authoritative air, Mr. Manafort thrived in political boiler rooms. But he distinguished himself even more as a lobbyist. He and two colleagues from his days with the Young Republicans and the Reagan campaign created two linked consulting firms that broke the mold in Washington, achieving legendary success. Shrewd and aggressive, Mr. Manafort, Charlie Black and Roger J. Stone helped elect politicians, then scored contracts to lobby those same politicians on behalf of businesses and foreign interests.

“After Reagan won the election, we started getting calls from people who wanted to know if we wanted to lobby,” Mr. Black said. “I didn’t think much of it,” he added, but Mr. Manafort “knew that it could be profitable.”

He also began to indulge his expensive tastes. He was attracted to displays of “opulence,” Mr. Stone said. “Manafort thought that if something was expensive, it meant it was good.”

His partners objected to some of his business expenses, questioning his Concorde flights to Paris and suites at the city’s lavish Hôtel de Crillon. In 1995, Mr. Manafort struck out on his own, focusing in part on clients in the former Soviet states where a clutch of oligarchs exercised control over entire industries. Washington seemed less hospitable. Mr. Manafort later told one associate that Karl Rove, the longtime Republican Party strategist, had “banished” him from the capital. In a 2016 memo seeking a position on Mr. Trump’s anti-establishment campaign, he cast his distance from the Republican elite as a positive.

By 2005, Mr. Manafort had forged bonds with two oligarchs in the former Soviet bloc. One was Oleg V. Deripaska, a Russian aluminum magnate who is close to President Vladimir V. Putin. One witness in Mr. Manafort’s trial testified that Mr. Deripaska lent Mr. Manafort $10 million in 2010, saying she saw no evidence it was ever repaid. Later, Mr. Deripaska sued him.

The other oligarch was Rinat Akhmetov, who with estimated assets of more than $12 billion was the richest man in Ukraine. At Mr. Akhmetov’s urging, Mr. Manafort agreed to try to engineer a political comeback for Mr. Yanukovych, a former coal trucking director, twice convicted of assault, who had lost a bid for the presidency in 2004.

In the words of federal prosecutors, Mr. Akhmetov and several other oligarchs backing Mr. Yanukovych became Mr. Manafort’s “golden goose.” Konstantin Kilimnik, a Russian citizen who prosecutors have said had ties to Russian intelligence, served as Mr. Manafort’s man on the ground in Kiev.

“Thank you for your unexpected generosity,” Mr. Manafort wrote to Mr. Yanukovych in an email with the subject line “bonuses” in 2010, the year that Mr. Yanukovych became Ukraine’s president.

Prosecutors allege that between 2010 and 2014, Mr. Manafort was paid more than $60 million from his Ukrainian patrons and hid much of that income in secret foreign bank accounts in the names of 15 or more shell companies. He avoided paying taxes on at least $16.5 million of it, they allege. The remainder, they said, might be considered nontaxable business expenses, construed broadly enough to include $45,000 for cosmetic dentistry.

Mr. Manafort used his tax-free dollars, prosecutors have said, to support a lifestyle of staggering extravagance. In 2012 alone, he bought three homes.

Mr. Gates has testified that he helped Mr. Manafort conceal his true income, hiding the foreign bank accounts from his accountants and disguising several million dollars in income as nontaxable loans from companies that Mr. Manafort secretly controlled.

Mr. Yanukovych’s fall from power in Ukraine in 2014 was cataclysmic for Mr. Manafort. Even though the oligarchs regrouped to fund a new political party for which Mr. Manafort worked, the payments to him dwindled fast, and he complained about unpaid bills. When Mr. Gates told him in April 2015 about his estimated tax bill for the previous year’s earnings, he erupted in anger. “WTF,” Mr. Manafort demanded in an email. “How could I be blindsided like this.”

“This is to calm down Paul,” Mr. Kilimnik, the Russian aide in Ukraine, wrote to Mr. Gates in mid-2015 in an email that promised that $500,000 would be wired soon.

Ukrainian prosecutors had begun investigating the payments to Mr. Manafort and others, turning to the F.B.I. for help. Agents interviewed both Mr. Manafort and Mr. Gates in 2014, but considered them only witnesses to the theft of Ukrainian government funds.

At about the same time, Mr. Manafort’s family confronted him over an affair he was having with a much younger woman, whose rent and credit card bill they believed he was paying, according to interviews and text messages hacked from one of his daughters. He entered an Arizona clinic to try to put his life back together, texting his younger daughter that he had emerged with newfound self-awareness.

But prosecutors claim that his schemes continued. They say he and Mr. Gates kept accountants at two firms and officials at three banks busy with a round robin of made-up explanations and doctored financial records.

For example, Mr. Manafort had falsely reported $1.5 million in income from Ukraine as a loan to lower his tax bill. He then claimed the same nonexistent loan had been “forgiven” in order to inflate his income so banks would agree to lend to him.

Paul Manafort and Rick Gates attempted to get Mr. Manafort out of financial trouble while they were working on the president’s campaign and inauguration, prosecutors say.

Trump campaign

Financial schemes

MARCH

2016

Paul Manafort is hired to manage Donald J. Trump’s strategy for the Republican convention. Rick Gates joins as his deputy.

Mr. Manafort secures a $3.4 million mortgage loan using false information, hid other debt and inflated his income with the help of Mr. Gates and his accountant.

APRIL

An expanded campaign role for Mr. Manafort is announced.

Mr. Manafort obtains a $1 million business loan from Banc of California using false information.

MAY

Mr. Manafort’s promotion to campaign chairman and chief strategist is announced.

Mr. Gates helps Mr. Manafort attempt to secure a fraudulent construction loan.

JUNE

JULY

Mr. Manafort and Mr. Gates attend the Republican National Convention in Cleveland.

Stephen M. Calk, the founder and chief executive of the Federal Savings Bank of Chicago, helps expedite a loan approval for Mr. Manafort. Days later, Mr. Manafort asks for his résumé.

AUG.

The Times reports on a ledger listing undisclosed cash payments earmarked for Mr. Manafort from a pro-Russian political party.

SEPT.

Mr. Trump hires Stephen K. Bannon as campaign chief, and Mr. Manafort resigns two days later. Mr. Gates becomes a liaison between the Republican National Committee and the campaign.

Mr. Manafort tells Mr. Calk that he must have had a “blackout” when he misrepresented his debts to him during a lunch.

OCT.

Mr. Gates helps Mr. Manafort doctor profit-and-loss statements to inflate his income for lenders.

Mr. Trump is elected. Mr. Gates eventually works on his inaugural committee.

NOV.

Mr. Calk helps secure a $9.5 million loan to Mr. Manafort. His bank later approves another $6.5 million loan.

Mr. Manafort asks Mr. Gates to promote Mr. Calk for a position in the administration.

By The New York Times

Mr. Manafort soon had plenty of detractors among the campaign staff. He won few points by calling Mr. Trump “Donald” in his first CNN appearance, as if he were Mr. Trump’s peer. Some aides suggested he was unfamiliar with all the changes in politics — most notably the rise of the internet — since 1996, when he last worked on an American presidential campaign. Others described him as lazy, carefully noting when he took off on Fridays for the Hamptons. Mr. Manafort said he had built a television studio at his home there so he could appear on Sunday talk shows remotely.

He lasted only five months, three of them as campaign chairman. When The New York Times revealed that a ledger found by Ukrainian investigators had listed $12.7 million in off-the-books cash payments to Mr. Manafort’s firm, one former campaign aide said that Mr. Trump was enraged. But another article detailing how Mr. Manafort and others were begging Mr. Trump to stop picking public fights equally angered Mr. Trump. When Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, told Mr. Manafort he was out, Mr. Trump was barely speaking to him.

By then, Mr. Manafort’s financial house of cards was on the verge of collapse. Less than two weeks after he left the campaign, one lender informed him that it had started to foreclose on his Brooklyn brownstone. He had paid cash for it when he was financially flush four years earlier, then borrowed $5.3 million against it that February. Five months had passed with no payments.

Mr. Gates managed to retain his affiliation to Mr. Trump as a liaison between the campaign and the Republican National Committee, although Mr. Trump disliked him so much that he was barred from flying on the candidate’s private plane. Mr. Manafort tried to use his lingering connection to Mr. Trump to land consulting work and to persuade banks to bail him out. He dangled a possible cabinet secretary post in front of Stephen Calk, chairman of Federal Savings Bank in Chicago, pressing Mr. Gates to promote him as a possible secretary of the Army.

He continued to treat Mr. Gates as his aide, asking him how to convert profit-and-loss statements from PDF format into Word in order, prosecutors said, to inflate his income and appear more creditworthy to banks. After the election, Mr. Calk approved two loans to Mr. Manafort for a total of $16 million. Mr. Manafort used some of it to save his Brooklyn property from foreclosure.

But even Mr. Calk was getting worried. On Dec. 7, 2016, he wrote to another top bank official: “Nervousness is setting in.” Less than a year later, Mr. Mueller’s team filed the first of a series of indictments against Mr. Manafort. Mr. Mueller granted a plea deal to Mr. Gates and immunity from prosecution to five of the nearly dozen witnesses for the prosecution.

Earlier versions of this article incorrectly identified an international lobbyist who worked for Mr. Manafort. She is Riva Levinson, not Rita Levinson.

Related Coverage: