https://truthout.org/articles/from-the-streets-of-la-to-the-national-stage-the-left-must-win-the-cultural-war

News Analysis

Culture & Media

From the Streets of LA to the National Stage: The Left Must Win the Cultural War

Trump’s war on dissent can only be defeated by a left that challenges the values sustaining authoritarianism.

by Henry A. Giroux

June 20, 2025

Truthout

Thousands of protesters rally in Downtown Los Angeles, California, during an anti-Trump demonstration on June 14, 2025. Barbara Davidson / Getty Images

Thousands of protesters rally in Downtown Los Angeles, California, during an anti-Trump demonstration on June 14, 2025. Barbara Davidson / Getty Images

On June 6, resistance ignited in the streets of Los Angeles to confront the Trump regime’s brutal campaign against immigrants, enforced by the brutality of ICE agents and the machinery of mass deportation. In a chilling escalation, Trump branded the protesters “insurrectionists” and threatened the use of military force — turning dissent into a crime and protest into a pretext for repression. Stephen Miller, White House deputy chief of staff, called Los Angeles “occupied territory,” adding, “We’ve been saying for years this is a fight to save civilization.”

This is not merely the rhetoric of strongman fantasies; it is the language of fascist ambition, a calculated pretext to invoke the Insurrection Act and erect a police state. Beneath this chilling facade lies something far more ominous: the weaponization of the war on immigrants as a means to orchestrate ethnic cleansing, veiled under the apparatus of law and the grotesque spectacle of state power. Moreover, as Kristi Noem and Trump have blatantly outlined, their assault on immigrants extends beyond individual lives — it’s a direct attack on the U.S.’s largest cities, like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York, which stand as Democratic Party strongholds. When they claim to be liberating these urban centers from “socialists,” they are not just declaring war on ideological foes, they are also setting the stage for a fascist takeover, one rooted in division and destruction. This is not about upholding law and order; it is the calculated weaponization of authoritarian culture to escalate state violence, instill terror, criminalize dissent, and legitimize white nationalist ideology. By framing defiance as treason, Trump attempts to cloak his own authoritarian crimes while constructing a political climate where any challenge to power is met with brutal retaliation. As Michelle Goldberg noted in The New York Times, “This is what autocracy looks like.”

The authoritarian dream is rooted in the belief that state violence should serve as the primary tool of governance. When the guardrails of democracy are dismantled, violence shifts from being a last resort to a governing principle. This is precisely what unfolded in Los Angeles, where Trump deployed the National Guard and Marines to crush protests against his mass deportation policies, while mobilizing ICE as a modern-day Gestapo. What cannot be ignored is that the militarization of civil society is not merely an overreaction or illegal response to a fabricated insurrection; it is the very foundation upon which martial law is established, paving the way for a fully realized fascist state. What unfolded in LA was not an insurrection; it was the people rising in defense of democracy. The true insurrection happened on January 6, with Trump as its chief architect. Yet once again, violence was being used not to protect democracy, but to crush it.

What we are witnessing is a spectacle of domination. The deployment of troops, the vigilante targeting of Democratic lawmakers, the planned grotesquerie of Trump’s military parade, and Trump’s order for ICE to target cities led by Democrats are not isolated events — they are scenes in the same authoritarian drama. Together, they represent a fusion of militarism and national identity, designed to normalize cruelty, fetishize strength, and recast obedience as patriotism. As Susan Sontag once warned, fascism cloaks violence in the aesthetics of spectacle — making submission not only palatable, but seductive. This is the pornography of power — where culture and repression merge in a theater of fear, scripted to extinguish political imagination and render dissent illegible.

If we are to reclaim democracy not as a slogan but as a living, breathing ethos, we must begin with culture.

In this moment of escalating violence, Trump’s use of force is more than a show of control — it is a pedagogical performance meant to normalize repression and etch it into public consciousness. This is fascist aesthetics reimagined for a media-saturated age, where power must not only be wielded but displayed as performance. Here, domination is choreographed, televised, and turned into a civic lesson. The spectacle becomes a tutorial in submission, transforming images of state violence into instruments of mass indoctrination. Culture is not summoned to illuminate reality but to obliterate it, replacing historical memory with myth, dissent with loyalty, and resistance with silence. The convergence of Trump’s militarized crackdown in Los Angeles and his self-aggrandizing parade of force reveals a machinery of destruction no longer hidden but flaunted, a grotesque exhibition engineered to numb the senses and turn state terror into a national ritual.

The Terrain of Culture Is Central in the Struggle Against Authoritarianism

In the current political moment, we would do well to remember Milan Kundera’s words from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting:

The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have someone write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long the nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was.

Indeed dominant culture is not peripheral to politics; it is its staging ground, its arsenal, and, increasingly, its most contested terrain. Authoritarianism does not rely solely on law or policy; it reshapes consciousness, manufactures consent, and weaves the logic of domination into the fabric of everyday life. Under Trump, culture is not merely an accessory to power – it is the weapon and the war zone.

Democracy is not shattered only by the blunt force of military coups; instead, it can be hollowed out from within, undermined by the ghosts of past tyrannies reanimated through symbols, digital technologies, and the ever-churning machinery of social media. Today, power speaks in the seductive language of images laced with bigotry, seeded with cruelty, and driven by the logic of exclusion and ethnic cleansing. Culture is no longer merely a reflection of the past; it has become its erasure. It functions as pedagogy — through what Ariella Aïsha Azoulay names as “imperial technologies,” and what I have called “disimagination machines.” It is designed to strip the colonized not only of their futures but of their histories, their very presence in the world. In this age of resurgent fascisms, we see its devastating effects in the genocidal assault waged by Israel against the Palestinian people, and in the scorched-earth war on historical memory and civic belonging carried out by the Trump regime in the United States. Culture is no longer a backdrop to political struggle — it is its very stage, its arsenal, and its battleground. Culture as an educational force is no longer subordinate to relations of power — it is the very essence of politics.

This is the pornography of power — where culture and repression merge in a theater of fear, scripted to extinguish political imagination and render dissent illegible.

As Catherine Caruso points out in Harvard News, “AI-powered autonomous weapons represent a new era in warfare and pose a concrete threat to scientific progress and basic research.” Yet the danger extends far beyond the battlefield. Artificial intelligence now plays an insidious role in shaping policy, normalizing militarism, censoring ethical debate, and legitimizing what can only be described as a culture of war. It reconfigures not only how we fight but also how we think — molding public consciousness in ways that privilege surveillance over solidarity, control over compassion.

For instance, the rise of artificial intelligence is accelerating a cultural transformation that is as dangerous as it is seductive. When OpenAI recently shut down its ChatGPT responses on the Gaza war for “safety” reasons, it wasn’t a glitch, — it was a warning. AI is not just organizing knowledge; it is curating memory, defining what can be said, and erasing what must be forgotten. In the wrong hands — and increasingly in the hands of authoritarian regimes and corporate overlords — AI becomes a weapon not of innovation but of ideological control. Brett Wilkins reports in Common Dreams that “commercial AI models are directly being used” by Israel in Gaza for mass surveillance and the targeting of “critics, dissidents, and opponents.” Culture, in this context, is no longer merely shaped by human struggle and historical memory; it is engineered, automated, and sanitized.

Too many on the left have long overlooked a fundamental truth: The real battle against gangster capitalism and its updated fascist versions is not solely over policies or economies but over culture itself — over the values, desires, and everyday practices that shape how people see the world and their place within it.

News Analysis

Culture & Media

From the Streets of LA to the National Stage: The Left Must Win the Cultural War

Trump’s war on dissent can only be defeated by a left that challenges the values sustaining authoritarianism.

by Henry A. Giroux

June 20, 2025

Truthout

On June 6, resistance ignited in the streets of Los Angeles to confront the Trump regime’s brutal campaign against immigrants, enforced by the brutality of ICE agents and the machinery of mass deportation. In a chilling escalation, Trump branded the protesters “insurrectionists” and threatened the use of military force — turning dissent into a crime and protest into a pretext for repression. Stephen Miller, White House deputy chief of staff, called Los Angeles “occupied territory,” adding, “We’ve been saying for years this is a fight to save civilization.”

This is not merely the rhetoric of strongman fantasies; it is the language of fascist ambition, a calculated pretext to invoke the Insurrection Act and erect a police state. Beneath this chilling facade lies something far more ominous: the weaponization of the war on immigrants as a means to orchestrate ethnic cleansing, veiled under the apparatus of law and the grotesque spectacle of state power. Moreover, as Kristi Noem and Trump have blatantly outlined, their assault on immigrants extends beyond individual lives — it’s a direct attack on the U.S.’s largest cities, like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York, which stand as Democratic Party strongholds. When they claim to be liberating these urban centers from “socialists,” they are not just declaring war on ideological foes, they are also setting the stage for a fascist takeover, one rooted in division and destruction. This is not about upholding law and order; it is the calculated weaponization of authoritarian culture to escalate state violence, instill terror, criminalize dissent, and legitimize white nationalist ideology. By framing defiance as treason, Trump attempts to cloak his own authoritarian crimes while constructing a political climate where any challenge to power is met with brutal retaliation. As Michelle Goldberg noted in The New York Times, “This is what autocracy looks like.”

The authoritarian dream is rooted in the belief that state violence should serve as the primary tool of governance. When the guardrails of democracy are dismantled, violence shifts from being a last resort to a governing principle. This is precisely what unfolded in Los Angeles, where Trump deployed the National Guard and Marines to crush protests against his mass deportation policies, while mobilizing ICE as a modern-day Gestapo. What cannot be ignored is that the militarization of civil society is not merely an overreaction or illegal response to a fabricated insurrection; it is the very foundation upon which martial law is established, paving the way for a fully realized fascist state. What unfolded in LA was not an insurrection; it was the people rising in defense of democracy. The true insurrection happened on January 6, with Trump as its chief architect. Yet once again, violence was being used not to protect democracy, but to crush it.

What we are witnessing is a spectacle of domination. The deployment of troops, the vigilante targeting of Democratic lawmakers, the planned grotesquerie of Trump’s military parade, and Trump’s order for ICE to target cities led by Democrats are not isolated events — they are scenes in the same authoritarian drama. Together, they represent a fusion of militarism and national identity, designed to normalize cruelty, fetishize strength, and recast obedience as patriotism. As Susan Sontag once warned, fascism cloaks violence in the aesthetics of spectacle — making submission not only palatable, but seductive. This is the pornography of power — where culture and repression merge in a theater of fear, scripted to extinguish political imagination and render dissent illegible.

If we are to reclaim democracy not as a slogan but as a living, breathing ethos, we must begin with culture.

In this moment of escalating violence, Trump’s use of force is more than a show of control — it is a pedagogical performance meant to normalize repression and etch it into public consciousness. This is fascist aesthetics reimagined for a media-saturated age, where power must not only be wielded but displayed as performance. Here, domination is choreographed, televised, and turned into a civic lesson. The spectacle becomes a tutorial in submission, transforming images of state violence into instruments of mass indoctrination. Culture is not summoned to illuminate reality but to obliterate it, replacing historical memory with myth, dissent with loyalty, and resistance with silence. The convergence of Trump’s militarized crackdown in Los Angeles and his self-aggrandizing parade of force reveals a machinery of destruction no longer hidden but flaunted, a grotesque exhibition engineered to numb the senses and turn state terror into a national ritual.

The Terrain of Culture Is Central in the Struggle Against Authoritarianism

In the current political moment, we would do well to remember Milan Kundera’s words from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting:

The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have someone write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long the nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was.

Indeed dominant culture is not peripheral to politics; it is its staging ground, its arsenal, and, increasingly, its most contested terrain. Authoritarianism does not rely solely on law or policy; it reshapes consciousness, manufactures consent, and weaves the logic of domination into the fabric of everyday life. Under Trump, culture is not merely an accessory to power – it is the weapon and the war zone.

Democracy is not shattered only by the blunt force of military coups; instead, it can be hollowed out from within, undermined by the ghosts of past tyrannies reanimated through symbols, digital technologies, and the ever-churning machinery of social media. Today, power speaks in the seductive language of images laced with bigotry, seeded with cruelty, and driven by the logic of exclusion and ethnic cleansing. Culture is no longer merely a reflection of the past; it has become its erasure. It functions as pedagogy — through what Ariella Aïsha Azoulay names as “imperial technologies,” and what I have called “disimagination machines.” It is designed to strip the colonized not only of their futures but of their histories, their very presence in the world. In this age of resurgent fascisms, we see its devastating effects in the genocidal assault waged by Israel against the Palestinian people, and in the scorched-earth war on historical memory and civic belonging carried out by the Trump regime in the United States. Culture is no longer a backdrop to political struggle — it is its very stage, its arsenal, and its battleground. Culture as an educational force is no longer subordinate to relations of power — it is the very essence of politics.

This is the pornography of power — where culture and repression merge in a theater of fear, scripted to extinguish political imagination and render dissent illegible.

As Catherine Caruso points out in Harvard News, “AI-powered autonomous weapons represent a new era in warfare and pose a concrete threat to scientific progress and basic research.” Yet the danger extends far beyond the battlefield. Artificial intelligence now plays an insidious role in shaping policy, normalizing militarism, censoring ethical debate, and legitimizing what can only be described as a culture of war. It reconfigures not only how we fight but also how we think — molding public consciousness in ways that privilege surveillance over solidarity, control over compassion.

For instance, the rise of artificial intelligence is accelerating a cultural transformation that is as dangerous as it is seductive. When OpenAI recently shut down its ChatGPT responses on the Gaza war for “safety” reasons, it wasn’t a glitch, — it was a warning. AI is not just organizing knowledge; it is curating memory, defining what can be said, and erasing what must be forgotten. In the wrong hands — and increasingly in the hands of authoritarian regimes and corporate overlords — AI becomes a weapon not of innovation but of ideological control. Brett Wilkins reports in Common Dreams that “commercial AI models are directly being used” by Israel in Gaza for mass surveillance and the targeting of “critics, dissidents, and opponents.” Culture, in this context, is no longer merely shaped by human struggle and historical memory; it is engineered, automated, and sanitized.

Too many on the left have long overlooked a fundamental truth: The real battle against gangster capitalism and its updated fascist versions is not solely over policies or economies but over culture itself — over the values, desires, and everyday practices that shape how people see the world and their place within it.

Capitalism Is Not Merely an Economic System

Historically, some strands of Marxist and progressive thought have dismissed culture as secondary or irrelevant — a critique that scholar Judith Butler powerfully challenged in their 1997 essay. They argued that the left’s cultural focus was wrongly seen as abandoning the materialist core of Marxist politics, often accused of being “factionalizing, identitarian, and [narrowly] particularistic.”

Downplaying the role of culture is not just a tactical misstep — it’s a fundamental error. As Antonio Gramsci warned, all politics is pedagogical, and every exercise of “hegemony” is inherently an educational act. In a capitalist society, the power of education does more than repress critical thought and informed consciousness, it actively shapes and empowers. It creates subjects, molds emotions, and defines what we accept as sensible.

AI is not just organizing knowledge; it is curating memory, defining what can be said, and erasing what must be forgotten.

As Theodor Adorno argued, capitalism is not merely an economic system but a totalizing cultural force, shaping desire through the “culture industry” — reducing human experience to commodified clichés and reinforcing conformity through repetition and distraction. Raymond Williams insisted that culture is both ordinary and political, embedded in the everyday practices through which people live and make meaning. Like Vaclav Havel, he believed that, “the political is not independent of the cultural, but it follows it.”

In this view, politics follows culture because the culture is the terrain in which politics establishes itself, the framework through which individuals are shaped, and the force that reproduces societies in ways that sustain distinct political systems. Stuart Hall’s work is crucial here in illuminating how culture is the site where ideology takes root, where identities are formed, contested, and secured. As Bruce Robbins notes in a commentary on Hall, the cultural theorist argued that everyday life could not be separated from politics as a matter of lived experience, and that culture could not be removed from “the political and economic structures that constrained it.”

This was particularly true for Hall’s critique of neoliberalism, which he viewed not only as an economic system but also as a pedagogical project. According to Hall, capitalism is not just enforced from above; it is lived, felt, and reproduced from below, woven into the most intimate structures of daily life, particularly given its notion that the market is the template for all social relations and embracing Margaret Thatcher’s toxic claim that there is no such thing as society.

Confronting the Current Dominant Culture of Cruelty

We are, in this Trumpian historical moment, suffocating under a dominant culture that functions as a powerful disimagination machine, shaping desires, identities, and common sense through a vast network of pedagogical sites, from social media and news platforms to advertising, entertainment, and relentless political spectacles. Education is no longer merely an institutional force; it has become the most decisive cultural arena where individual and collective consciousness is produced and contested. Hall understood this with prophetic clarity. For him, culture is never outside politics, it is the terrain on which political struggle is fought, particularly through the politics of identification.

Later in his life, Hall warned that the left had failed to grasp the educative dimension of politics, the need to transform not just policies but the very framework through which people interpret the world and their place in it. In a 2012 interview with The Guardian’s Zoe Williams, Hall put it bluntly: “The left is in trouble. It’s not got any ideas, it’s not got any independent analysis of its own, and therefore it’s got no vision. It just takes the temperature: ‘Whoa, that’s no good, let’s move to the right.’ It has no sense of politics being educative, of politics changing the way people see things.”

For Hall, without this pedagogical imperative, the left forfeits its ability to generate hope, build alliances, and forge new political subjectivities: The promise of democracy is torn asunder. In the shadow of rising state terrorism, bodies are broken, abducted, and freedoms extinguished. Silence spreads like a fog. It blankets the cries of the young, the starving children of Gaza; lives obliterated by bombs and buried by indifference as entire families are killed by Israel in Gaza. The horror knows no borders, reproduced at home as immigrant youth in the United States are torn from their families, thrust into a trauma so vast it swallows the future.

Trump’s budget, which he calls “one big, beautiful bill,” is a deliberate weapon of mass inequality, ruthlessly crafted to fatten the coffers of the financial elite while punishing the most vulnerable.

Meanwhile, as Peter Baker notes in The New York Times, the demagogue-in-chief revels in gifts from dictators, ranging from a luxury flying palace from Qatar to collecting “$320 million in fees from a new cryptocurrency” and shamelessly brokering “overseas real estate deals worth billions of dollars.” Trump displays his vast corruption while openly normalizing the widespread abuse of presidential power. How else to explain his “opening an exclusive club in Washington called the Executive Branch [while] charging $500,000 apiece to join,” all the while presiding over a regime that slashes “funding for health care, food and education through some of the largest cuts in U.S. history, while even raising taxes on many low-income families”?

This is a Trump-Musk-engineered culture of cruelty, ramped up to grotesque extremes, a form of state terrorism that Bill Gates aptly describes as “killing the world’s poorest children,” both here and abroad. Beneath the surface, the agenda is clear: Trump’s budget, which he calls “one big, beautiful bill,” is a deliberate weapon of mass inequality, ruthlessly crafted to fatten the coffers of the financial elite while punishing the most vulnerable. In addition, it has the “potential to increase the federal deficit by up to $3.8 trillion over the next decade.” This monstrous budget, born from the twisted minds of Trump and his MAGA sycophants, is so brutal that Paul Krugman condemns it as a product of “sadistic zombies,” a horrifying manifestation of cruelty that reflects the regime’s moral decay. His anger is rightly focused on a budget that slashes taxes for the ultra-wealthy while funneling endless resources into instruments of state violence, all in the name of control, domination, and the obliteration of any semblance of social justice, both within our borders and beyond.

This is more than a policy crisis. It is a cultural catastrophe. Fascism today is not only wrapped in lawless decrees and armed repression, it is also cloaked in spectacles of cruelty and a language steeped in hate and terminal exclusion. Trump’s fervent advocates, Elon Musk and Steve Bannon, raise Nazi salutes, as though rehearsing for the dark future they are determined to summon. Stephen Miller channels Hitler’s rhetoric under the guise of patriotism, declaring that “America is for Americans and Americans only.” Trump resurrects the Confederacy, embracing its monuments, symbols, and genocidal logic. In their hands, the culture of fascism is not hidden. It is performed, televised, and normalized. The horror of fascist violence is back, though it is now draped in AI-guided bombs, ethnic cleansing, and white supremacists basking in their project of racial cleansing while destroying every vestige of decency, human rights, and democracy.

What we are witnessing is the death not just of democracy but of moral and civic conscience itself. A collective numbness has settled in, a culture of forgetting, cruelty and complicity, where silence speaks louder than resistance, enabling the violence to grow unchecked. In part, this is fueled by an anti-intellectualism and culture that embraces civic illiteracy, a culture of immediacy that banishes informed judgment and contemplation, and institutions that embrace critical thought as a foundation for creating critical citizens. We are not merely talking about the death of the imagination, but an attack on any institutions that provide what Hannah Arendt once called “thinking without a banister.”

This is more than a policy crisis. It is a cultural catastrophe.

At the heart of this decay lies a cultural ethos cultivated by capitalism for decades: to live is to consume, selfishness is freedom, personal responsibility eclipses systemic problems, and solidarity is weakness. Culture has become a site of struggle, now more intense than ever, amplified by new digital technologies, social media, podcasts, and a host of other pedagogical platforms. These platforms not only disempower resistance but also amplify the forces of domination, shaping the contours of public discourse and ideological control. Society fragments further, social atomization rises, and the numbing routines of a consumer-driven spectacle are matched by what Jonathan Crary calls “vacant forms of attentiveness.”

Corporate-controlled cultural apparatuses now hold immense pedagogical and political power, reshaping the relationship between power, culture, and daily life. Everyday existence is captive to new modes of socialization, a tsunami of fragmentation, and the dissolution of society, driven by the morally numbing routines of a punishing state and its ever-expanding criminalization of free speech and social problems. In such a climate, the ideological mobilization of memory, agency, and desire becomes inseparable from the pedagogical construction of neoliberal public spaces and civic life, laying the foundation for an emerging authoritarianism.

Also central to this emerging fascism is a culture in which memory is rendered inaccessible, critical thinking is scorned, and dissent is branded as treason, subject to harsh penalties imposed by a regime of terror — one that includes abductions, attacks on due process, an unprecedented assault on higher education, and a growing political culture of corruption and lawlessness.

This isn’t to suggest that culture is simply absorbed into an all-encompassing system of domination, subjugated by the unchecked power of brutal billionaires and Vichy-like politicians. On the contrary, culture has moved to the front lines of struggle, central to the effort to normalize gangster capitalism, erase institutions that promote democratic values, and create an army of loyal fascist subjects. The vicious attacks by the Trump administration on higher education, public schools, journalists, oppositional media, and dissident politicians demonstrate the fear of Trump and his enablers who recognize the power of these institutions in potentially educating students and the wider public to hold power accountable, to engage in refusal rather than in conformity, adaptation, and political resignation.

At the same time, the right’s attacks have eroded the responsibility of institutions like Columbia University to stand against Trump’s assault on academic freedom and free speech. In failing to resist, they become complicit in what Chris Hedges describes as “capitulations and crackdowns on pro-Palestine activism,” resulting in the suspension, expulsion, and firing of students and professors protesting the genocide in Gaza.

In this context, as I recently stated in an interview on Courage My Friends podcast, that critical education is the glue that connects hope, justice, and the fight for a real, radical democracy. If we fail to recognize the centrality of education, the left will be in serious trouble. But equally crucial is the need to rethink the power of culture as a site of both domination and empowerment, a site that holds profound pedagogical, economic, and political significance in the digital age.

Building a Culture of Solidarity

Cultural politics has a long legacy in Marxist thought, from Gramsci and Hall, to Robin D.G. Kelley, the Frankfurt School and the Situationists, to the radical movements of the 1960s and the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement. It’s time to reignite and propel this work forward, to shape it anew in the crucible of our present crisis and the urgency of this historical moment.

What we are witnessing is the death not just of democracy but of moral and civic conscience itself.

Late former Uruguayan President José Mujica, in one of his speeches, reprinted in Jacobin, argued poignantly that capitalism is not just property relations but a set of cultural values that the Left must confront with a culture of solidarity. He argued strongly that social change could not be reduced to changing capitalist economies and that “capitalism is a culture” with enormous power that must be understood, analyzed and resisted. The late cultural critic Ellen Willis adds to this insight by noting that at the core of cultural politics is the recognition “that the project of organizing a democratic political movement necessarily entails the hope that one’s ideas and beliefs are not merely idiosyncratic but speak to vital human needs, interests, and desires, and therefore will be persuasive to many and ultimately most people.”

Mujica’s reflection on the limits of revolutionary strategy underscores the crucial role of culture in any transformative movement, emphasizing that without a profound shift in cultural consciousness, systemic change remains unattainable. This insight directly ties into the larger thesis that fascism cannot be countered merely through political and economic reforms but requires a radical transformation of culture itself, a cultural shift that challenges the very values and ideologies that sustain authoritarianism. He makes clear that struggles over culture are not just about struggles over meaning and identity, but struggles over power, human freedom and equality.

Mujica’s lament is our warning. My generation, he said, made the mistake of believing that revolution meant taking over the means of production. Some of us thought we could change the system without changing the culture. But capitalism, he insisted, survives not through force alone, but through the everyday values it instills, values stronger than any army. You cannot build a new world with people shaped by the old one: “You cannot build a socialist building with bricklayers who are capitalists,” he warned, because their consciousness will reproduce the very system they seek to overthrow.

This insight could not be more relevant and urgent. If we are to resist the death cult of fascism, if we are to reclaim democracy not as a slogan but as a living, breathing ethos, we must begin with culture. Not the commodified culture of products and performances, but culture in its deepest sense: the web of values, relationships, and meanings that shape how we live and what we imagine possible. We need, in short, a cultural revolution rooted in a politics of solidarity, care, limits, and humility. To be revolutionary today means more than redistributing wealth and changing economic structures, however fundamental. It also means redefining what it means to live well. It means teaching each other to resist the seductions of greed and the numbness of cruelty. It means building new ways of being together, of listening, of imagining. As Mujica said, “Poor is the one who needs a lot.” The left must reclaim a culture of enough, of sufficiency rather than excess, of cooperation rather than conquest.

Culture, as an educational force, does more than mirror society — it challenges dominant ideologies, unsettles normalized values, and disrupts the social relations that sustain oppression. It cultivates a critical awareness of how power operates, but awareness alone is not enough. Knowledge must ignite action. Critical consciousness must be bound to collective struggles — to movements that confront the machinery of poverty, the cruelty of inequality, the devastation of climate collapse, and the enduring violence of systemic racism. Without this fusion of insight and resistance, culture risks becoming reflection without consequence, critique without transformation.

The challenge for left progressives and others is to produce an anti-capitalist culture that provides the modes of literacy, comprehensive analysis, historical consciousness, and vision to make clear and resist a long legacy of colonialism with its fantasies of displacement, dispossession, and extermination. One cannot be silent or ignore a cultural politics in which Trump calls for a policy that amounts to the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from northern Gaza.

Trump’s neocolonial vision of an ethnically cleansed Gaza is not policy; it’s cultural imperialism draped in empire, a death wish spoken aloud, a nightmare clawing its way into daylight. The rigor mortis of ethical and political decay, born from colonial and imperial fantasies, is made even more visible by Trump’s call to annex Canada, Panama, and Greenland. Intoxicated with power, this resurgent view of globalization is fashioned on a toxic mix of greed, fear, delusions of grandeur, and cruelty. This is cultural politics in the service of death, a form of politics that not only perpetuates violence but also reshapes society in its own image, normalizing annihilation and dispossession as acceptable byproducts of imperial ambition.

There is no future without a cultural shift away from gangster capitalism. Without it, the left risks fading into a mere ghost, clinging to slogans while the world burns, as the politics of extermination, displacement, and ethnic cleansing rage on. The horrors of the past are back, but so too must be our memory, our imagination, and our courage to begin again — not as mourners of a failed nostalgia, but as creators of a new, insurgent radical democratic culture. A culture that remembers the children, hears the silences, and refuses to let the future be stolen without a fight. The fight against fascism demands a new language, one that integrates materialist and cultural concerns, where the critique of structural domination is inseparable from cultural and educational struggles. This language must reshape how we think about power, justice, and agency, emphasizing the need for a critical pedagogy and cultural transformation that challenges the ideologies sustaining authoritarianism while empowering collective resistance.

In this struggle, pedagogy is not peripheral; it is the front line. Education, culture, and daily life are the terrains where fascism is either normalized or resisted. This is where mass consciousness takes root and where the seeds of a transformative political movement are sown. Despair is not an option; it is surrender. In an era when silence is complicity and culture is weaponized to erase memory and stifle dissent, what’s needed is a revolutionary pedagogy, a cultural politics that teaches us to remember, to resist, and to reimagine the world. As the late political philosopher Sheldon Wolin warned, “the central challenge of our time … is about nurturing a discordant democracy,” a task that depends on awakening “the civic consciousness of the nation.” This means placing culture at the very heart of politics — where critique, agency, and the radical imagination converge.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Henry A. Giroux

Henry A. Giroux currently holds the McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the English and Cultural Studies Department and is the Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy. His most recent books include: The Terror of the Unforeseen (Los Angeles Review of books, 2019), On Critical Pedagogy, 2nd edition (Bloomsbury, 2020); Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy: Education in a Time of Crisis (Bloomsbury 2021); Pedagogy of Resistance: Against Manufactured Ignorance (Bloomsbury 2022) and Insurrections: Education in the Age of Counter-Revolutionary Politics (Bloomsbury, 2023), and coauthored with Anthony DiMaggio, Fascism on Trial: Education and the Possibility of Democracy (Bloomsbury, 2025). Giroux is also a member of Truthout’s board of directors.

Part of the Series

The Public Intellectual

…Reading List

Politics & Elections

Mamdani’s Massive Victory Should Show Democrats Where the Party’s Future Lies

Economy & Labor

Trump Is Setting the US Economy Up for Another Great Financial Crisis

War & Peace

It’s Time to Put an End to the US-Israeli Fantasy of Regime Change in Iran

Politics & Elections

Mike Johnson Suggests War Powers Act Is Unconstitutional

Politics & Elections

Zionists Tried to Make NYC Race About Israel. Zohran Mamdani Didn’t Give In.

Politics & Elections

Voters Will “Get Over It,” McConnell Tells GOP Colleagues About Medicaid Cuts

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fascism_in_the_United_States

Fascism in the United States

Fascism in the United States is an expression of fascist political ideology that dates back over a century in the United States, with roots in white supremacy, nativism, and violent political extremism. Although it has had less scholarly attention than fascism in Europe, particularly Nazi Germany, scholars say that far-right authoritarian movements have long been a part of the political landscape of the U.S.[1]

Scholars point to early 20th-century groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and domestic proto-fascist organizations that existed during the Great Depression as the origins of fascism in the U.S. These groups flourished amid social and political unrest.[1] Alongside homegrown movements, German-backed political formations during World War II worked to influence U.S. public opinion towards the Nazi cause. After the U.S.'s formal declaration of war against Germany, the U.S. Treasury Department raided the German American Bund's headquarters and arrested its leaders. Both during and after World War II, Italian anti-fascist activists and other anti-fascist groups played a role in confronting these ideologies.

Events such as the 2017 Charlottesville rally have exposed the persistance of racism, antisemitism, and white supremacy within U.S. society. The resurgence of fascist rhetoric in contemporary U.S. politics, particularly under the administration of Donald Trump, has highlighted the persistence of far-right ideologies and it has also rekindled questions and debates surrounding fascism in the United States.[1]

Part of a series on Fascism

Early origins

The origins of fascism in the United States date back to the late 19th century with the passage of Jim Crow laws in the American South, the rise of the eugenicist discourse in the U.S., and the intensification of nativist and xenophobic hostility towards immigrants. During the early 20th century, several groups were formed in the United States that contemporary historians have classified as fascist organizations – with a prominent example being the Ku Klux Klan.[1]

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan parade in Washington, D.C., September 13, 1926

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), or "the Klan," is an American Protestant-led Christian extremist, white supremacist, far-right hate group founded in 1865 during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era in the devastated South.

Scholars have characterized the Klan as America's first terrorist group[2][3][4][5] and compared its emergence to fascist trends in Europe.[6] Historian Peter Amann states that: "Undeniably, the Klan had some traits in common with European fascism—chauvinism, racism, a mystique of violence, an affirmation of a certain kind of archaic traditionalism—yet their differences were fundamental. ... [The KKK] never envisioned a change of political or economic system."[7]

The first Klan, founded by Confederate veterans, assaulted and murdered politically active Black people and their white political allies in the South.[8] The second Klan was formed in 1915 as a small group in Georgia and flourished nationwide by the mid-1920s.[9]

Inter-war period

The rise of fascism in Europe during the interwar period raised concerns in the U.S.; however, European fascist regimes were largely viewed positively by the American ruling class. This was because fascist interpretations of ultranationalism allowed a nation to gain a significant amount of economic influence in the Western world and permitted a nation's government to destroy leftists and labor movements.[10]

Sympathy with Italian fascism

Poet Ezra Pound in prison (1945)

During the 1920s, American scholars frequently wrote about the rise of Italian fascism under Benito Mussolini, but few of them supported it; however, Mussolini's fascist policies initially gained widespread support among Italian Americans.[11][12]

William Phillips, who served as the American ambassador to Italy, was "greatly impressed by the efforts of Benito Mussolini to improve the conditions of the masses" and found "much evidence" in support of the fascist argument that "they represent a true democracy in as much as the welfare of the people is their principal objective."[13]

Phillips found Mussolini's achievements "astounding [and] a source of constant amazement" and greatly admired his "great human qualities." United States Department of State officials enthusiastically agreed with Phillips' assessment, praising Italian fascism for having "brought order out of chaos, discipline out of license, and solvency out of bankruptcy," as well as Mussolini's "magnificent" achievements in Ethiopia during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.[13]

The American poet Ezra Pound moved from the United States to Italy in 1924, becoming a loyal supporter of Benito Mussolini, the founder of a fascist state. He wrote articles and produced radio broadcasts that were critical of the United States, international bankers, Franklin Roosevelt, and the Jews. His propaganda was poorly received in the U.S.[14]

In November 1925, the Order Sons of Italy in America helped organize the first U.S. Fascist convention in Philadelphia. The goal of the convention was "setting up Fascist infiltration into political organizations and mutual aid societies so as to create friendly ties and spiritual agreement".[15] After World War II, the organization faced criticism for the "heavy involvement by the OSIA in Mussolini's Fascist propaganda campaign in the 1920s and 1930s".[16]

Black Legion

Main article: Black Legion (political movement)

Black Legion's uniform and weapons, posed by police officers after arrests

In 1925, Virgil Effinger established the paramilitary Black Legion, a violent white supremacist offshoot of the KKK that sought to establish fascism in the United States by launching a revolution against the federal government.[17] The Black Legion was active in the Midwestern United States in the 1920s and the 1930s and grew to prominence during the Great Depression. The FBI estimated its membership numbered "at 135,000, including a large number of public officials, including Detroit's police chief."[18] Historians have suggested lower estimates.[19][20]

The Black Legion is widely viewed as having been an even more violent and radical offshoot of the Klan.[21] In 1936, the group was suspected of having killed as many as 50 people, according to the Associated Press, including Charles Poole, an organizer for the federal Works Progress Administration. Eleven men were found guilty of Poole's murder.[18] The Associated Press described the organization as "a group of loosely federated night-riding bands operating in several States without central discipline or common purpose beyond the enforcement by lash and pistol of individual leaders' notions of 'Americanism.'"[22] Nearly 50 Legionnaires were ultimately convicted of murder, conspiracy to commit murder, kidnapping, arson, and perjury.[23] Although it was responsible for numerous attacks, the Black Legion remained limited in size and ultimately petered out.[17]

Father Charles Coughlin

Father Charles Coughlin (right) on the cover of Time magazine (1934)

Father Charles Coughlin was a Roman Catholic priest who hosted a prominent radio program in the late 1930s, on which he often ventured into politics. In 1932, he backed and welcomed the election of President Franklin Roosevelt, but the two had a falling out after 1934. His radio program and his newspaper, "Social Justice," denounced Roosevelt, as well as the "big banks" and "the Jews."[24] When the United States entered World War II, the U.S. government took his radio broadcasts off the air and blocked his newspaper from the mail. He abandoned politics but remained a parish priest until he died in 1979.[24]

The American architect-to-be Philip Johnson was a correspondent (in Germany) for Coughlin's newspaper between 1934 and 1940 (before beginning his architectural career). He wrote articles that were favorable to the Nazis and critical of "the Jews," as well as taking part in a Nazi-sponsored press tour, in which he covered the 1939 Nazi invasion of Poland. He quit the newspaper in 1940, was investigated by the FBI, and was cleared for army service in World War II. Years later, he would refer to these activities as "the stupidest thing[sic] I ever did ... [which] I never can atone for."[25]

Rise of Hitler

Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933.[26] In the years that followed, before the outbreak of World War II, some German-Americans attempted to create pro-Nazi movements in the U.S., often bearing swastikas and wearing uniforms.[27] These groups had little to do with Nazi Germany, and they lacked support from the wider German-American community.[28]

Across the U.S., so many small groups sprang up wearing uniforms and identifying as fascist that in 1934, the American Civil Liberties Union released a pamphlet titled "Shirts! A Survey of the New 'Shirt' Organizations in the United States Seeking a Fascist Dictatorship" detailing the gold, silver, brown, black, gray, white and blue-colored shirt liveries of the different emergent fascist groups.[29]

In May 1933, Heinz Spanknöbel, a German immigrant to America, received authority from Rudolf Hess, the deputy führer of Germany, to form an official American branch of the Nazi Party. The branch was known as the Friends of New Germany in the U.S.[28] The Nazi Party referred to it as the National Socialist German Workers' Party of the U.S.A.[26] Though the party had a strong presence in Chicago, it remained based in New York City, having received support from the German consul in the city. Spanknöbel's organization was openly pro-Nazi. Members stormed the German-language newspaper New Yorker Staats-Zeitung and demanded that the paper publish articles sympathetic to Nazis. Spanknöbel's leadership was short-lived, as he was deported in October 1933 following revelations that he had not registered as a foreign agent.[28]

Some American corporations had branches in neutral countries that traded with Germany after the U.S. declared war in late 1941.[30]

German American Bund

Flag of the German American Bund (1936)

The German American Bund was the most prominent and well-organized fascist organization in the United States. It was founded in 1936, following the model of Hitler's Nazi Germany. It appeared shortly after the founding of several smaller groups, including the Friends of New Germany and the Silver Legion of America, founded in 1933 by William Dudley Pelley and the Free Society of Teutonia. The Friends of New Germany dissolved in December 1935 when Hess ordered all German citizens to leave the group after realizing that the organization was not beneficial to advancing their cause.[31]

The German American Bund, led by Fritz Kuhn, was formed in 1936 and lasted until America formally entered World War II in 1941. The Bund existed with the goal of a united America under ethnic German rule and following Nazi ideology. It proclaimed communism as its main enemy and expressed anti-Semitic attitudes.[28] After March 1, 1938, membership in the German-American Bund was only open to American citizens of German descent.[32][33] Its main goal was to promote a favorable view of Nazi Germany. The Bund was active, providing its members with uniforms and encouraging participation in "training camps."[34]

Poster for Bund rally at Madison Square Garden (1939)

Inspired by the Hitler Youth, the Bund created its youth division, where members "took German lessons, received instructions on how to salute the swastika, and learned to sing the 'Horst Wessel Lied' and other Nazi songs."[35] The Bund continued to justify and glorify Hitler and his movements in Europe during the outbreak of World War II. After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Bund leaders released a statement demanding that America stay neutral in the ensuing conflict and expressed sympathy for Germany's war effort. The Bund reasoned that this support for the German war effort was not disloyal to the United States, as German-Americans would "continue to fight for a Gentile America free of all atheistic Jewish Marxist elements."[35]

The Bund held rallies with Nazi insignia and procedures such as the Hitler salute. Its leaders denounced the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jewish-American groups, communism, "Moscow-directed" trade unions, and American boycotts of German goods.[36] They claimed that George Washington was "the first Fascist" because he did not believe that democracy would work.[37]

The high point of the Bund's activities was their rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City on February 20, 1939, with around 20,000 people in attendance.[38] The anti-Semitic speakers repeatedly referred to President Roosevelt as "Frank D. Rosenfeld," calling his New Deal the "Jew Deal," as well as denouncing the supposed Bolshevik-Jewish American leadership.[39] The rally ended with violence between protesters and the Bund's "storm-troopers."[40] In 1939, America's top fascist, the Bund's leader Fritz Julius Kuhn, was investigated by the city of New York and was found to be embezzling the Bund's funds for his personal use. He was arrested, his citizenship was revoked, and he was deported.

The U.S. Army organized a draft in 1940 to bring citizens into military service. The Bund advised its members not to submit to the draft. Based on this advice, the U.S. government outlawed the Bund, and Kuhn fled to Mexico.

After many internal and leadership disputes, the Bund's executive committee agreed to disband the party on December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 11, 1941, the United States formally declared war on Germany, and Treasury Department agents raided Bund headquarters. The agents seized all records and arrested 76 Bund leaders.[35]

World War II

Canada and the United States battled the Axis powers during World War II. As part of the war effort, they suppressed the fascist movements within their borders, which were already weakened by the widespread public perception that they were fifth columns. This suppression consisted of the internment of fascist leaders, the disbanding of fascist organizations, the censorship of fascist propaganda, and pervasive government propaganda against fascism. In the U.S., this campaign of suppression culminated in "The Great Sedition Trial" of November 1944, in which George Sylvester Viereck, Lawrence Dennis, Elizabeth Dilling, William Dudley Pelley, Joe McWilliams, Robert Edward Edmondson, Gerald Winrod, William Griffin, and, in absentia, Ulrich Fleischhauer were all put on trial for aiding the Nazi cause, supporting fascism and isolationism. However, after the judge's death, a mistrial was declared, and all charges were dropped.[41]

Post-World War II

Hermine Braunsteiner, the first Nazi war criminal to be extradited from the United States, pictured during her time in the SS

In the 1980s, the Office of Special Investigations estimated around ten thousand Nazi war criminals entered the United States from Eastern Europe after the conclusion of World War II, albeit the number has since been determined to have been much smaller.[42][43]

Some were brought in Operation Paperclip, a project to bring German scientists and engineers to the U.S. Most Nazi collaborators entered the United States through the 1948 and 1950 Displaced Persons Acts and the Refugee Relief Act of 1953. Supporters of the acts exhibited only slight awareness that Nazi war criminals would exploit the legislation to enter the United States. Most of the supporters' concern was about disallowing known communists from entering. This shift of focus was likely due to the pressures of the Cold War in the years after World War II when the United States focused on countering Soviet communism more than Nazism.[42]

During the 1950s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service conducted several investigations into suspected Nazi war criminals. No official trials came from these investigations. The Holocaust and the possibility of Nazi collaborators living in the country entered the national discussion in the 1960s with the trial of Adolf Eichmann, accusations of war criminals during Soviet war crimes trials, and a series of articles published by Charles R. Allen detailing the presence of Nazi war criminals living in the U.S. The federal government began to focus on uncovering Nazi war criminals remaining in the country.[42]

Public awareness of the Holocaust and remaining Nazi war criminals increased in the 1970s. Many cases made headline news. The case of Hermine Braunsteiner, the first Nazi war criminal to be extradited from the United States, received widespread media coverage. The case triggered the Immigration and Naturalization Service to locate Nazi collaborators further. By the late 1970s, INS addressed thousands of cases, and the U.S. government formed the Office of Special Investigations, which was dedicated to locating Nazi war criminals in the United States.[42]

Neo-Nazism

See also: Neo-Nazism

Neo-Nazism began to emerge as an ideology in the 1970s, seeking to revive and implement Nazi ideology.[44] In the United States, organizations such as the American Nazi Party, the National Alliance, and White Aryan Resistance were formed during the second half of the 20th century.[45] While initially composed of distinctive movements, in the 21st century, many U.S. Neo-Nazi groups have moved towards more decentralized organization and online social networks with a terroristic focus.[46]

American Nazi Party

George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party, at a hearing of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1963

In 1959, the American Nazi Party was founded by George Lincoln Rockwell, a former U.S. Navy commander, who was dismissed from the Navy due to his espousal of fascist political views.[47]

Headquartered in Arlington, Virginia, the organization was initially named the World Union of Free Enterprise National Socialists, intended to denote opposition to state ownership of property. The same year—it was renamed the American Nazi Party to attract 'maximum media attention.'[48]

The party was based primarily upon the ideals and policies of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party in Germany during the Nazi era and embraced its uniforms and iconography. Since the late 1960s, several small groups had used the name "American Nazi Party," with most being independent of each other and disbanding before the 21st century.[49][A]

On August 25, 1967, Rockwell was shot and killed in Arlington by John Patler, a former party member who had previously been expelled by Rockwell due to his espousal of his alleged "Bolshevik leanings."[47] The party was dissolved in 1983.

National Alliance

National Alliance member with a Nazi flag at a rally in Washington, D.C., August 2002

The National Alliance is a neo-Nazi,[53] white supremacist[53][54][55][56] political organization founded by William Luther Pierce, author of The Turner Diaries, in 1974 and based in Mill Point, West Virginia. It was the largest and most active neo-Nazi group in the United States in the 1990s.[57][45] In 2002, its membership was estimated at 2,500 with an annual income of $1 million.[58]

Its membership declined after Pierce died in 2002, and after a split in its ranks in 2005, it became largely defunct.[53][59] According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the National Alliance had lost most of its members by 2020 but is still visible in the U.S.[57][46] Other groups, such as Atomwaffen Division, have taken its place.[60]

National Socialist Movement

The National Socialist Movement (NSM or NSM88)[fn 1] is a US-based Neo-Nazi organization that was founded in 1974.[61][62] The Anti-Defamation League has described the NSM as "one of the more explicitly neo-Nazi groups in the United States." It seeks the transformation of the United States into a white ethnostate from which Jews, non-Whites, and members of the LGBTQ community would be expelled and barred from citizenship.[63][64]

NSM rally on the west lawn of the United States Capitol building, Washington, D.C., in 2008

Once considered to be the largest and most prominent neo-Nazi organization in the United States, its membership has plummeted since the late 2010s.[63] It is a part of the Nationalist Front[65] and is classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.[64]

2017 Charlottesville rally

Main article: Unite the Right rally

Rally participants preparing to enter Emancipation Park in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 12, 2017, carrying Neo-Confederate flags, Confederate battle flags, Gadsden flags, a Nazi flag, and a flag depicting Mjölnir

From 11 to 12 August 2017, the Unite the Right rally, a white-nationalist event,[66][67][68] took place in Charlottesville, Virginia.[69][70][71] It was organized by Richard B. Spencer and Jason Kessler, both Neo-Nazism adherents.[72][73][74][75] Marchers included members of the alt-right,[76] neo-Confederates,[77] neo-fascists,[78] white nationalists,[79] neo-Nazis,[80] Klansmen,[81] and far-right militias.[82]

Some groups chanted racist and antisemitic slogans and carried weapons, Nazi and neo-Nazi symbols, the valknut, Confederate battle flags, Deus vult crosses, flags, and other symbols of various past and present antisemitic and anti-Islamic groups.[87] The organizers' stated goals included the unification of the American white nationalist movement[76] and opposing the proposed removal of the statue of General Robert E. Lee from Charlottesville's former Lee Park.[85][88] The rally sparked a national debate over Confederate iconography, racial violence, and white supremacy.[89]

Patriot Front

Patriot Front is an American white supremacist and neo-fascist hate group.[90] Part of the broader alt-right movement, the group split off from the neo-Nazi organization Vanguard America in the aftermath of the Unite the Right rally in 2017.[91][92][93][94]

Patriot Front's aesthetic combines traditional Americana with fascist symbolism. Internal communications within the group indicated it had approximately 200 members as of late 2021.[95] According to the Anti-Defamation League, the group generated 82% of reported incidents in 2021 involving the distribution of racist, antisemitic, and other hateful propaganda in the United States, comprising 3,992 incidents in every continental state.[96]

Donald Trump and fascism

Main article: Donald Trump and fascism

See also: Alt-right, Political positions of Donald Trump, Racial views of Donald Trump, Radical right (United States), and Trumpism

Historians and election experts have compared Trump's anti-democratic tendencies and egotistical personality to the sentiments and rhetoric of Benito Mussolini and Italian fascism.[97]

There has been significant academic and political debate over whether Donald Trump, the 45th and 47th president of the United States, can be considered a fascist, especially during his 2024 presidential campaign and second term as president.

Trumpism has been likened to Benito Mussolini's Italian fascism by critics of Trump,[98] and significant academic debate exists over the prevalence of fascism and neo-fascism within Trumpism.[99][100] Historians and election experts have compared Trump's anti-democratic tendencies and egotistical personality to the sentiments and rhetoric of Benito Mussolini and Italian fascism.[97] Several scholars have rejected comparisons with fascism, instead viewing Trump as authoritarian and populist.[101][102]

Madeleine Albright, the former secretary of state, warned in a book about Fascism in 2018.[103] Some scholars have drawn comparisons between the political stylings of Donald Trump and fascist leaders. Such assessments began during Trump's 2016 presidential campaign,[104][105] continuing throughout the first Trump presidency as he appeared to court far-right extremists,[106][107][108][109] including his attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election after losing to Joe Biden,[110] and culminating in the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[111]

Protest sign at a rally in 2018 describing Donald Trump as a fascist

The January 6 United States Capitol attack has been compared to the Beer Hall Putsch.

The attack on the United States Capitol by supporters of Donald Trump on January 6, 2021, has been compared to the Beer Hall Putsch,[112] a failed coup attempt in Germany by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler against the Weimar government in 1923.[113]

In "Trump and the Legacy of a Menacing Past," Henry Giroux argued that understanding the rise of "fascist politics" in the U.S. necessitates examining the power of language, social media, and public spectacle in fostering American-style fascism.[114] Jason Stanley argued in 2018 that Trump employed "fascist techniques" to mobilize his base and weaken liberal democratic institutions.[115] Trump has also been compared to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi,[116] while former aide Anthony Scaramucci compared Trump to Benito Mussolini and Augusto Pinochet.[117]

Since Trump was elected to office in 2016, many academics have compared Trump's politics to fascism. Several have pointed out that contrasts exist between historical fascism and Trump's politics. Many also argued that "fascist elements" have operated within and around Trump's movement. Following the January 6 attack, some voices within the academic community felt that things had changed and that Trump's politics and connections with fascism deserved greater scrutiny.[118][119] According to an October 2024 poll held by ABC News and Ipsos, 49% of American registered voters considered Trump to be a fascist,[a] defined in the poll as "a political extremist who seeks to act as a dictator, disregards individual rights and threatens or uses force against their opponents", while 23% considered Kamala Harris to be a fascist.[120] Another YouGov survey from the same year reported that about 20% of Americans believed that Trump saw Hitler as completely bad; among Republican respondents, four in ten believed that Trump held such position. The same poll reported that nearly half of Trump voters would continue to support a political candidate even if he or she stated that Hitler had done some good things, a position that was held by a quarter of all respondents.[121]

Anti-fascism

See also: Anti-fascism and Antifa (United States)

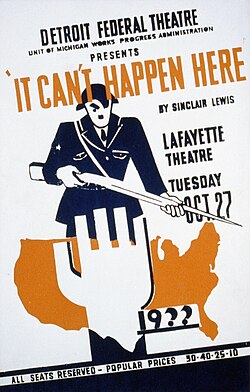

Poster for the stage adaptation of It Can't Happen Here, October 27, 1936, at the Lafayette Theater as part of the Detroit Federal Theatre

The attack on the United States Capitol by supporters of Donald Trump on January 6, 2021, has been compared to the Beer Hall Putsch,[112] a failed coup attempt in Germany by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler against the Weimar government in 1923.[113]

In "Trump and the Legacy of a Menacing Past," Henry Giroux argued that understanding the rise of "fascist politics" in the U.S. necessitates examining the power of language, social media, and public spectacle in fostering American-style fascism.[114] Jason Stanley argued in 2018 that Trump employed "fascist techniques" to mobilize his base and weaken liberal democratic institutions.[115] Trump has also been compared to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi,[116] while former aide Anthony Scaramucci compared Trump to Benito Mussolini and Augusto Pinochet.[117]

Since Trump was elected to office in 2016, many academics have compared Trump's politics to fascism. Several have pointed out that contrasts exist between historical fascism and Trump's politics. Many also argued that "fascist elements" have operated within and around Trump's movement. Following the January 6 attack, some voices within the academic community felt that things had changed and that Trump's politics and connections with fascism deserved greater scrutiny.[118][119] According to an October 2024 poll held by ABC News and Ipsos, 49% of American registered voters considered Trump to be a fascist,[a] defined in the poll as "a political extremist who seeks to act as a dictator, disregards individual rights and threatens or uses force against their opponents", while 23% considered Kamala Harris to be a fascist.[120] Another YouGov survey from the same year reported that about 20% of Americans believed that Trump saw Hitler as completely bad; among Republican respondents, four in ten believed that Trump held such position. The same poll reported that nearly half of Trump voters would continue to support a political candidate even if he or she stated that Hitler had done some good things, a position that was held by a quarter of all respondents.[121]

Anti-fascism

See also: Anti-fascism and Antifa (United States)

Poster for the stage adaptation of It Can't Happen Here, October 27, 1936, at the Lafayette Theater as part of the Detroit Federal Theatre

During World War II

American singer-songwriter and anti-fascist Woody Guthrie and his guitar labeled "This machine kills fascists"

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts, in September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. As political refugees from Mussolini's regime, they disagreed among themselves on whether to ally with communists and anarchists or to exclude them. In 1942, the Mazzini Society joined other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference in Montevideo, Uruguay. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members, Carlo Sforza, to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the overthrow of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy.[122][123]

Post-World War II

During the Second Red Scare, which occurred in the United States in the years that immediately followed the end of World War II, the term "premature anti-fascist" came into currency. It was used to describe Americans who had actively agitated or worked against fascism, such as Americans who had fought for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War before fascism was seen as a proximate and existential threat to the United States (which only occurred generally after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and only occurred universally after the attack on Pearl Harbor). The implication was that such persons were either communists or communist sympathizers whose loyalty to the United States was suspect.[124][125][126] However, the historians John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr have written that no documentary evidence has been found of the U.S. government referring to American members of the International Brigades as "premature antifascists": the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Office of Strategic Services, and United States Army records used terms such as "Communist," "Red," "subversive," and "radical" instead. Indeed, Haynes and Klehr indicate that they have found many examples of members of the XV International Brigade and their supporters referring to themselves sardonically as "premature antifascists."[127]

Since the 1980s

Main article: Antifa (United States)

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts, in September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. As political refugees from Mussolini's regime, they disagreed among themselves on whether to ally with communists and anarchists or to exclude them. In 1942, the Mazzini Society joined other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference in Montevideo, Uruguay. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members, Carlo Sforza, to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the overthrow of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy.[122][123]

Post-World War II

During the Second Red Scare, which occurred in the United States in the years that immediately followed the end of World War II, the term "premature anti-fascist" came into currency. It was used to describe Americans who had actively agitated or worked against fascism, such as Americans who had fought for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War before fascism was seen as a proximate and existential threat to the United States (which only occurred generally after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and only occurred universally after the attack on Pearl Harbor). The implication was that such persons were either communists or communist sympathizers whose loyalty to the United States was suspect.[124][125][126] However, the historians John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr have written that no documentary evidence has been found of the U.S. government referring to American members of the International Brigades as "premature antifascists": the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Office of Strategic Services, and United States Army records used terms such as "Communist," "Red," "subversive," and "radical" instead. Indeed, Haynes and Klehr indicate that they have found many examples of members of the XV International Brigade and their supporters referring to themselves sardonically as "premature antifascists."[127]

Since the 1980s

Main article: Antifa (United States)

Anti-fascists with banner reading "good night white pride"

Antifascist activists with a modified anarchist red and black flag and a transgender pride flag containing the hammer and sickle in a 2017 protest

Protesters hold an antifa banner in Minneapolis on February 18, 2017.

Modern antifa politics can be traced back to opposition to the infiltration of Britain's punk scene by white power skinheads in the 1970s and 1980s and the emergence of neo-Nazism in Germany following the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Germany, young leftists, including anarchists and punk fans, renewed the practice of street-level anti-fascism. Columnist Peter Beinart writes that "in the late '80s, left-wing punk fans in the United States began following suit, though they initially called their groups Anti-Racist Action (ARA) on the theory that Americans would be more familiar with fighting racism than they would be with fighting fascism".[128]

Dartmouth College historian Mark Bray, author of Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, credits the ARA as the precursor of modern antifa groups in the United States. In the late 1980s and 1990s, ARA activists toured with popular punk rock and skinhead bands to prevent Klansmen, neo-Nazis, and other assorted white supremacists from recruiting.[129][130] Their motto was "We go where they go," meaning they would confront far-right activists in concerts and actively remove their materials from public places.[131] In 2002, the ARA disrupted a speech in Pennsylvania by Matthew F. Hale, the head of the white supremacist group World Church of the Creator, resulting in a fight and twenty-five arrests. In 2007, Rose City Antifa, likely the first group to utilize the name antifa, was formed in Portland, Oregon.[132][133][134] Other antifa groups in the United States have other genealogies. In 1987, in Boise, Idaho, the Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment (NWCAMH) was created in response to the Aryan Nation's annual meeting near Hayden Lake, Idaho. The NWCAMH brought together over 200 affiliated public and private organizations and helped people across six states--Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming.[135] In Minneapolis, Minnesota, a group called the Baldies was formed in 1987 with the intent to fight neo-Nazi groups directly. In 2013, the "most radical" chapters of the ARA formed the Torch Antifa Network,[136] which has chapters throughout the United States.[137] Other antifa groups are a part of different associations, such as NYC Antifa, or operate independently.[138]

Modern anti-fascism in the United States is a highly decentralized movement. Antifa political activists are anti-racists who engage in protest tactics, seeking to combat fascists and racists such as neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and other far-right extremists.[139] This may involve digital activism, harassment, physical violence, and property damage[140] against those whom they identify as belonging to the far-right.[141][142] According to antifa historian Mark Bray, most antifa activity is nonviolent, involving poster and flyer campaigns, delivering speeches, marching in protest, and community organizing on behalf of anti-racist and anti-white nationalist causes.[143][133]

A June 2020 study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies of 893 terrorism incidents in the United States since 1994 found one attack staged by an anti-fascist that led to a fatality (the 2019 Tacoma attack, in which the attacker, who self-identified as an anti-fascist, was killed by police), while attacks by white supremacists or other right-wing extremists resulted in 329 deaths.[144][145][146] Since the study was published, one homicide has been connected to anti-fascism.[144] A DHS draft report from August 2020 similarly did not include "antifa" as a considerable threat while noting white supremacists as the top domestic terror threat.[147]

There have been multiple efforts to discredit Antifa groups via hoaxes on social media, many of them false flag attacks originating from alt-right and 4chan users posing as Antifa backers on Twitter.[148][149] Some hoaxes have been picked up and reported as fact by right-leaning media.[150][151]

During the George Floyd protests in May and June 2020, the Trump administration blamed Antifa for orchestrating the mass demonstrations. Analysis of federal arrests did not find links to Antifa.[152] There had been repeated calls by the Trump administration to designate Antifa as a terrorist organization, a move that academics, legal experts, and others argued would both exceed the authority of the presidency and violate the First Amendment.[153][154][155][156]

Modern antifa politics can be traced back to opposition to the infiltration of Britain's punk scene by white power skinheads in the 1970s and 1980s and the emergence of neo-Nazism in Germany following the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Germany, young leftists, including anarchists and punk fans, renewed the practice of street-level anti-fascism. Columnist Peter Beinart writes that "in the late '80s, left-wing punk fans in the United States began following suit, though they initially called their groups Anti-Racist Action (ARA) on the theory that Americans would be more familiar with fighting racism than they would be with fighting fascism".[128]