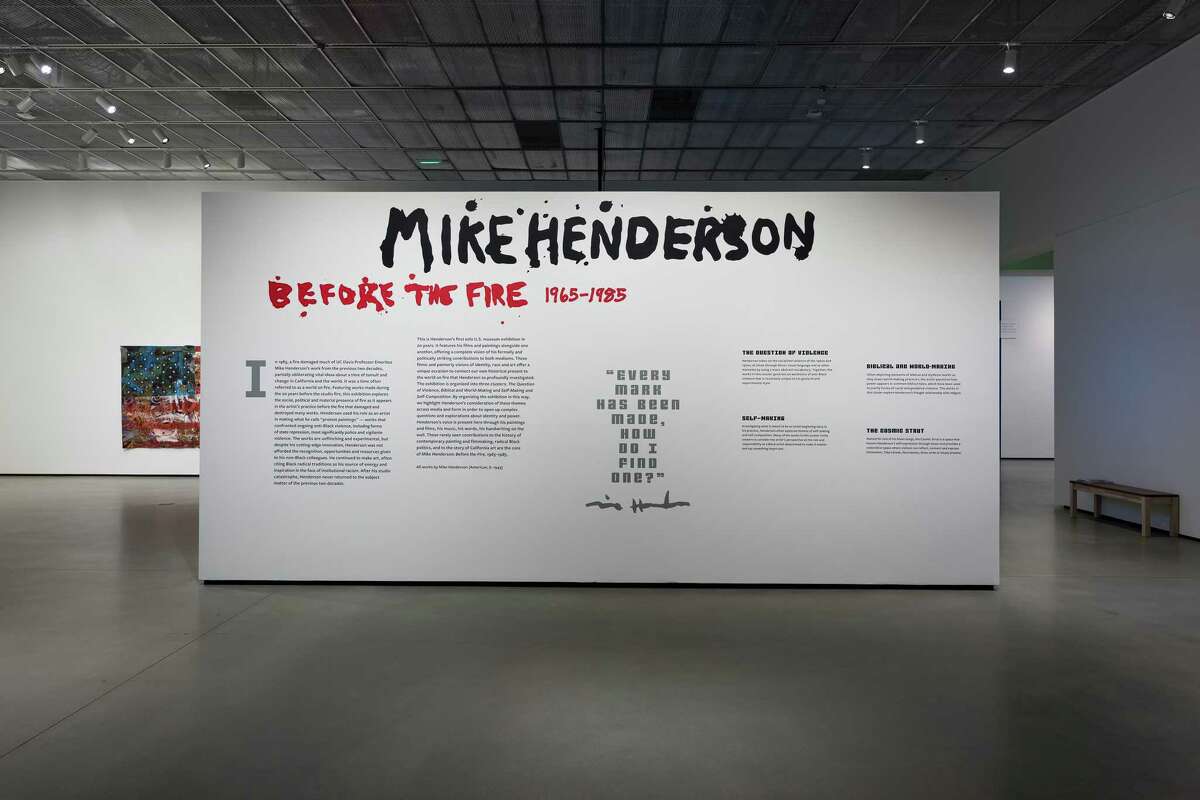

Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965–1985

Mike Henderson (b. 1944) is a painter, filmmaker, and professor emeritus at University of California, Davis. Published to accompany his first museum retrospective, this catalog surveys Henderson’s paintings and films from 1965 to 1985, which are rooted as much in Francisco Goya’s horror of humanity as in Sun Ra’s hope for a new Black future. In the work of that time, Henderson depicted scenes of racial violence, heteromasculinity, and abject social conditions with force and unflinching directness.

In 1985, a studio fire damaged much of Henderson’s output from the previous two decades, obscuring vital ideas about a time of tumult and change, often referred to as a world on fire. Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965–1985 addresses Henderson’s multifaceted art of that period, which examined and offered new ideas about Black life in the visual languages of protest, Afrofuturism, and surrealism.

Published in association with the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis

Exhibition dates:

Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art

January 29–June 25, 2023

Mike Henderson

Works | Bio | Press | Exhibition Views

American, b. 1943

Lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area, California

Mike Henderson is a pioneering African American artist, filmmaker and musician, whose dynamic practice has spanned more than fifty years. Born and raised in Marshall, Missouri, he moved to the Bay Area to attend the San Francisco Art Institute in 1965. His early, breakthrough figurative paintings from this period reveal the spirit of protest and social justice in 1960s San Francisco, as well as the vibrant community of artists and friends that would nourish his creativity for decades to come.

Henderson received his MFA from the SFAI in 1970, and soon left behind his figurative style, turning his artistic vision increasingly towards abstraction. Today, he is known for abstract, highly gestural paintings that demonstrate a palpable connection to post-war abstraction and a defining instinct for improvisation. Henderson’s lived experiences, conversations he has heard, and places he has visited—those moments that “stick to your retinas”—are all conjured up in his work through texture, form, and color.

In addition to painting, Henderson is an accomplished blues guitarist and filmmaker. His experimental short films have been screened at venues around the world, including recent presentations at the New York Film Festival (Lincoln Center); the Gene Siskel Film Center (Chicago); Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris); and the Academy Museum (Los Angeles, CA).

Mike Henderson has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1973) and two National Endowment for the Arts Artist Grants (1989, 1978). He was recently awarded the 2019 Artadia San Francisco Award and 2022 Margrit Mondavi Arts Medallion. Henderson’s paintings and films have been exhibited in such distinguished institutions as Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA; Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA; de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY; and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL. He is the subject of recent solo exhibitions in the Bay Area including his first museum retrospective, Before the Fire, 1965-1985 at the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, UC Davis, CA (2023); Chicken Fingers, 1976–1980 at Haines Gallery (2023); Honest to Goodness at the San Francisco Art Institute (2019); At the Edge of Paradise at Haines Gallery (2019); and was included in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 at the de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA (2019).

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520388055/mike-henderson

Disciplines Art Modern & Contemporary Art

Mike Henderson Before the Fire, 1965–1985

by Sampada Aranke (Editor), Dan Nadel (Editor)

January 2023

First Edition

Hardcover

$45.00, £38.00

Title Details

Rights: Available worldwide

Pages: 128

ISBN: 9780520388055

Trim Size: 9.5 x 10.75

Illustrations: 60 color illustrations

Share

Recommend to Your Library (PDF)

About the Book From Our Blog About the Author Related Books

ABOUT THE BOOK:

The first major exhibition and catalog dedicated to the work of groundbreaking painter and filmmaker Mike Henderson.

Mike Henderson (b. 1944) is a painter, filmmaker, and professor emeritus at University of California, Davis. Published to accompany his first museum retrospective, this catalog surveys Henderson’s paintings and films from 1965 to 1985, which are rooted as much in Francisco Goya’s horror of humanity as in Sun Ra’s hope for a new Black future. In the work of that time, Henderson depicted scenes of racial violence, heteromasculinity, and abject social conditions with force and unflinching directness.

In 1985, a studio fire damaged much of Henderson’s output from the previous two decades, obscuring vital ideas about a time of tumult and change, often referred to as a world on fire. Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965–1985addresses Henderson’s multifaceted art of that period, which examined and offered new ideas about Black life in the visual languages of protest, Afrofuturism, and surrealism.

Published in association with the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis

Exhibition dates:

Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art

January 29–June 25, 2023

From Our Blog:

Black History Month 2023: Art and Artists

Books featuring Black artists Throughout the month of February, UC Press will highlight books we have had the privilege to publish. Books featured will raise up Black voices, highlight the works of …

Black History Month 2023: Art and Artists

Books featuring Black artists Throughout the month of February, UC Press will highlight books we have had the privilege to publish. Books featured will raise up Black voices, highlight the works of …

ABOUT THE ARTIST/AUTHOR:

Mike Henderson is a pioneering African American artist, filmmaker and musician, whose dynamic practice has spanned more than fifty years. Born and raised in Marshall, Missouri, he moved to the Bay Area to attend the San Francisco Art Institute in 1965. He has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1973) and two National Endowment for the Arts Artist Grants (1989, 1978), and he was recently awarded the 2019 Artadia San Francisco Award.

ABOUT THE EDITORS:

Sampada Aranke, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has appeared in e-flux, Artforum, Art Journal, ASAP/J, and October and in catalogues for Sadie Barnette, Betye Saar, Rashid Johnson, Faith Ringgold, and many others. Her book, Death's Futurity: The Visual Life of Black Power, will be published in February 2023.

Dan Nadel is former Curator at Large of the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis. He has mounted exhibitions including What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art: 1960 to the Present; Gertrude Abercrombie; Kathy Butterly | ColorForm; and Chicago Comics, 1960s to Now. Nadel is the author and editor of several books, including Peter Saul: Professional Artist Correspondence, 1945–1976; The Collected Hairy Who Publications 1966–1969; and It’s Life As I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940–1980.

Mike Henderson (b. 1944) is a painter, filmmaker, and professor emeritus at University of California, Davis. Published to accompany his first museum retrospective, this catalog surveys Henderson’s paintings and films from 1965 to 1985, which are rooted as much in Francisco Goya’s horror of humanity as in Sun Ra’s hope for a new Black future. In the work of that time, Henderson depicted scenes of racial violence, heteromasculinity, and abject social conditions with force and unflinching directness.

In 1985, a studio fire damaged much of Henderson’s output from the previous two decades, obscuring vital ideas about a time of tumult and change, often referred to as a world on fire. Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965–1985 addresses Henderson’s multifaceted art of that period, which examined and offered new ideas about Black life in the visual languages of protest, Afrofuturism, and surrealism.

Published in association with the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis

Exhibition dates:

Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art

January 29–June 25, 2023

‘I could have died’: how an artist rebuilt his career after a studio fire

Much of Mike Henderson’s ‘protest paintings’ were destroyed after a fire but in his first solo exhibition for decades he shows what was recovered and restored

“The difference between a good life and a bad life,” begins a line attributed to psychiatrist Carl Jung, “is how well you walk through the fire.”

Artist Mike Henderson knows the purging, clarifying effects of conflagration. In 1985 a blaze ripped through his home studio, damaging much of his work from the previous two decades. But that moment of destruction was also one of creation.

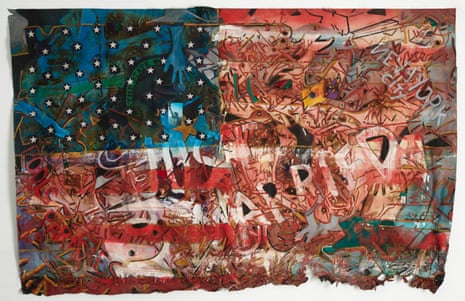

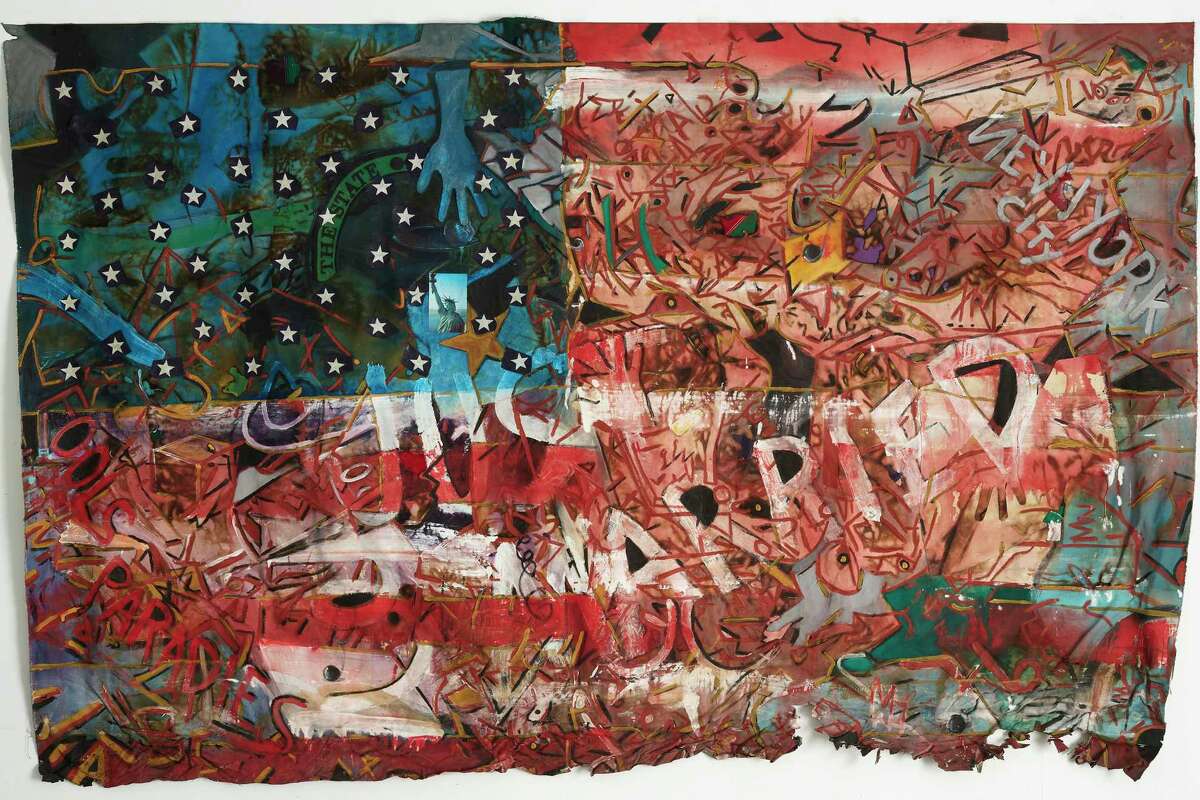

Mike Henderson - Love it or Leave it, I Will Love it if You Leave it, 1976 Photograph: Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery. Photo: Robert Divers Herrick

“The difference between a good life and a bad life,” begins a line attributed to psychiatrist Carl Jung, “is how well you walk through the fire.”

Artist Mike Henderson knows the purging, clarifying effects of conflagration. In 1985 a blaze ripped through his home studio, damaging much of his work from the previous two decades. But that moment of destruction was also one of creation.

“I came to realise that the fire was a changing part in my life,” the 79-year-old says via Zoom from his home in San Leandro near Oakland, California. “I could have died if I stayed in there. I started looking at my life in terms of relationships and what life is about. Raising a family: I wouldn’t have done that. I decided to clear out my life so I could find that person.”

Henderson did and has now been married for more than 30 years, though he ruefully waves a finger at the camera to show that he recently lost his wedding ring – he had removed it to put on some rubber gloves and believes it was stolen by workmen at his home.

The painter, film-maker and blues musician is now preparing for his first solo exhibition in 20 years. Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965-1985 opened last week at the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at the University of California, Davis.

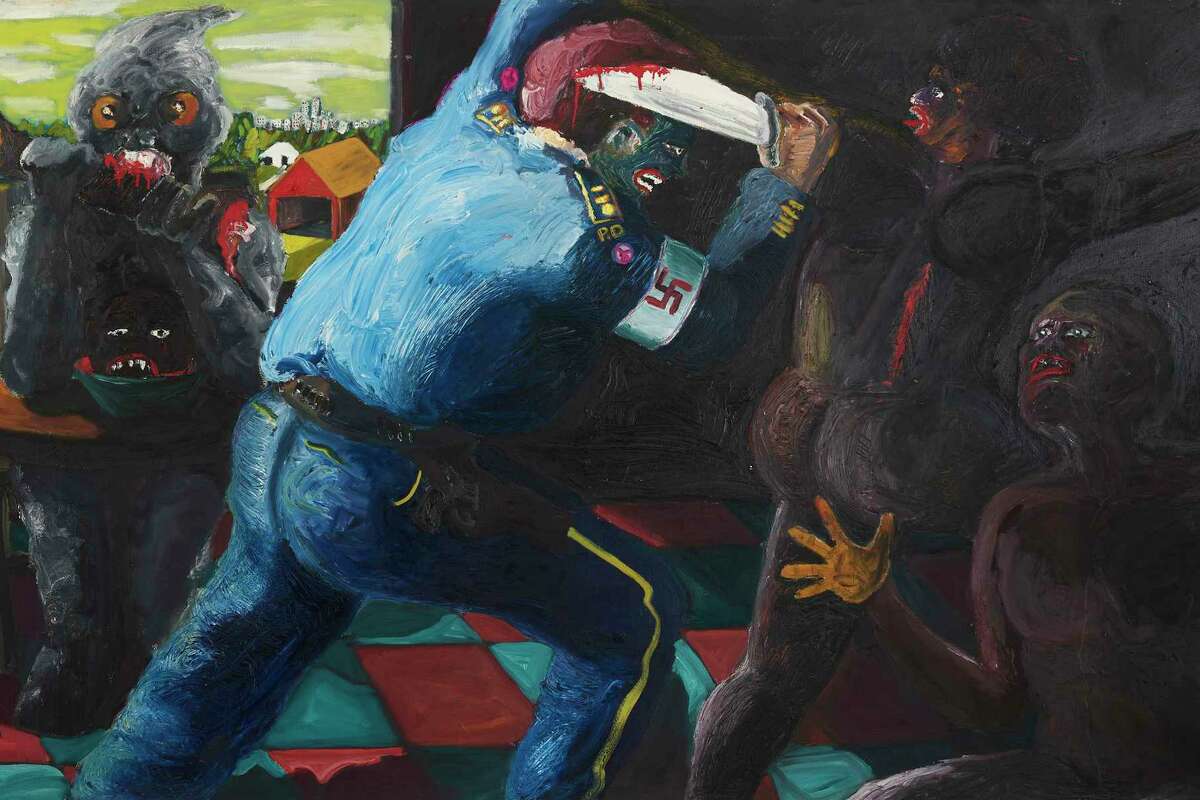

It is a rare chance to see Henderson’s big, figurative “protest paintings” depicting the racist violence and police brutality of the civil rights era. The show includes many pieces that were thought lost in the fire but have been recovered and restored by the museum. There is also a slideshow of damaged artworks to illuminate the dozens of paintings that were beyond salvation.

It has been a long journey here. Henderson grew up in a home that lacked running water in Marshall, Missouri, during the era of Jim Crow segregation. His mother was a cook; his father worked in a shoe factory and as a janitor. “We were poor,” he recalls, reclining in a chair under a blue baseball cap. “We couldn’t even spell ‘poor’. We couldn’t get the P.”

But attending Sunday sermons at church with his grandmother, Henderson was moved by the religious paintings. “I was an oddball because I was still a dreamer. I had these dreams of something else like wanting to be an artist or wanting to play the guitar. It didn’t make much sense. You’ve got to be a football player, athlete, you go to the army, you get married, you live two doors down from your parents and it repeats all over again. Sit around and tell lies in the barbershop and so forth. I tried to fit in but didn’t.”

Severely dyslexic, he quit school when he was 16 but returned at 21. A visit to a Vincent van Gogh exhibition in Kansas City proved inspiring and life-changing. In 1965 Henderson rode west on a Greyhound bus to study at the San Francisco Art Institute, then the only racially integrated art school in America. He found a community of artists and kindred spirits from backgrounds very different from his own.

“I went as an empty container. I had no opinions about anything so I was like a sponge just sucking it all up. I was around students whose parents were New York artists, kids who travelled the world. Real diverse: Indians, Koreans, Chinese, Japanese and different tribes of Native Americans. I made it a habit to mingle with everybody that I could to find out whatever it was that I didn’t know.”

This was also the tumultuous era of civil rights demonstrations, protests against the Vietnam war and, in Oakland, the birth of the Black Panthers, a political organisation that aimed to combine socialism, Black nationalism and armed defence against police brutality.

The rallies were culturally and racially diverse, Henderson recalls. “There’s a common thread here; everybody’s feeling something here. Everybody was questioning everything and saying, why are we fighting? It was like a magnet that glued me to it and I was just taking it all in.”

He smiles when he thinks back to one anti-war protest where a limousine pulled up and a woman got out, kissed him and exclaimed: “Harry, I haven’t seen you in years!” It was the singer-songwriter Joan Baez. Henderson, tongue-tied, managed to point out, “I’m not Harry!” Baez excused herself, got back in the limo and went to the civic centre, where Henderson watched her perform the Lord’s Prayer.

But it was also a revolutionary moment in art – bad timing for a fledgling figurative painter who idolised Goya, Rembrandt and Van Gogh. “In the 60s, painting was dead. Conceptual art, film-making, the new stuff was coming in. How was I going to make a living from it? I don’t know.

“I knew one thing. I wasn’t going to be on my deathbed wondering why I didn’t try. I knew that the protest paintings I was doing weren’t going to hang in anybody’s living room but the paintings were coming through me. There was a deeper calling. It wasn’t about, will it sell or is it popular? It’s coming out of me and I had no control of it. It controlled me.”

It was a financial struggle. Henderson sometimes had popcorn for dinner and depended on student loans or the kindness of strangers. But in 1970 he joined the groundbreaking UC Davis art faculty, teaching for 43 years alongside Wayne Thiebaud, Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest, Manuel Neri and William T Wiley (he retired in 2012 as professor emeritus).

In 1985 he took a sabbatical from UC Davis to play in a band touring Switzerland. But during his first weekend away, he learned that his home in San Francisco had been destroyed by fire. “It was like the rug was yanked from under my feet when my landlord called me and told me that everything was gone,” he says.

“Wow, the first thing I did was get rid of all the liquor around me because I wanted to bounce and that was going to fog my brain. I was in shock. When I got back, I found out later things weren’t as bad. There were some paintings that were saved.”

And thankfully the fire had stopped at the door of a storage closet containing Henderson’s precious films of blues musicians such as Big Mama Thornton. “When the landlord told me the whole block was gone, I first thought about that film. The paintings I could do again, perhaps, but I could never replace those films.”

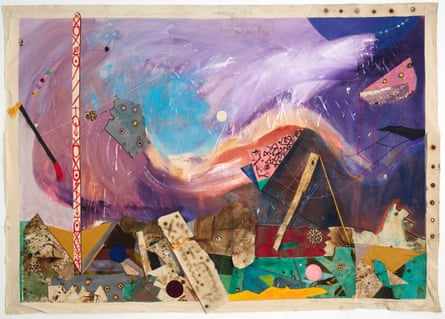

Henderson did not resume work on protest paintings after the fire. Instead his later work explores Black life and utopian visions through abstraction, Afro-futurism and surrealism. He reflects: “I didn’t want to paint figures any more. I felt like I was through with figures.”

His home was gone and he could no longer afford to live in San Francisco – “I’m not Rauschenberg!” – so he found a place in Oakland instead. “It was a big change and I did a lot of soul searching why I was there. I knew there was only one way to go and that was to go forward.

“I remember thinking I’m like in a trench. I can’t go over the right side or left side. I can’t go back. I have to go forward and just keep on going, see where this leads, and maybe I can climb out of this trench. Eventually I moved on and got married and had a son: he’s a wildlife biologist. I couldn’t complain because I chose art. So whatever he chooses is OK with me!”

Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965-1985 is now on show at the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at the University of California, Davis

https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/mike-henderson-after-fire-18136259.php

Fire destroyed 20 years of Mike Henderson’s work. But it also turned his art in a new direction

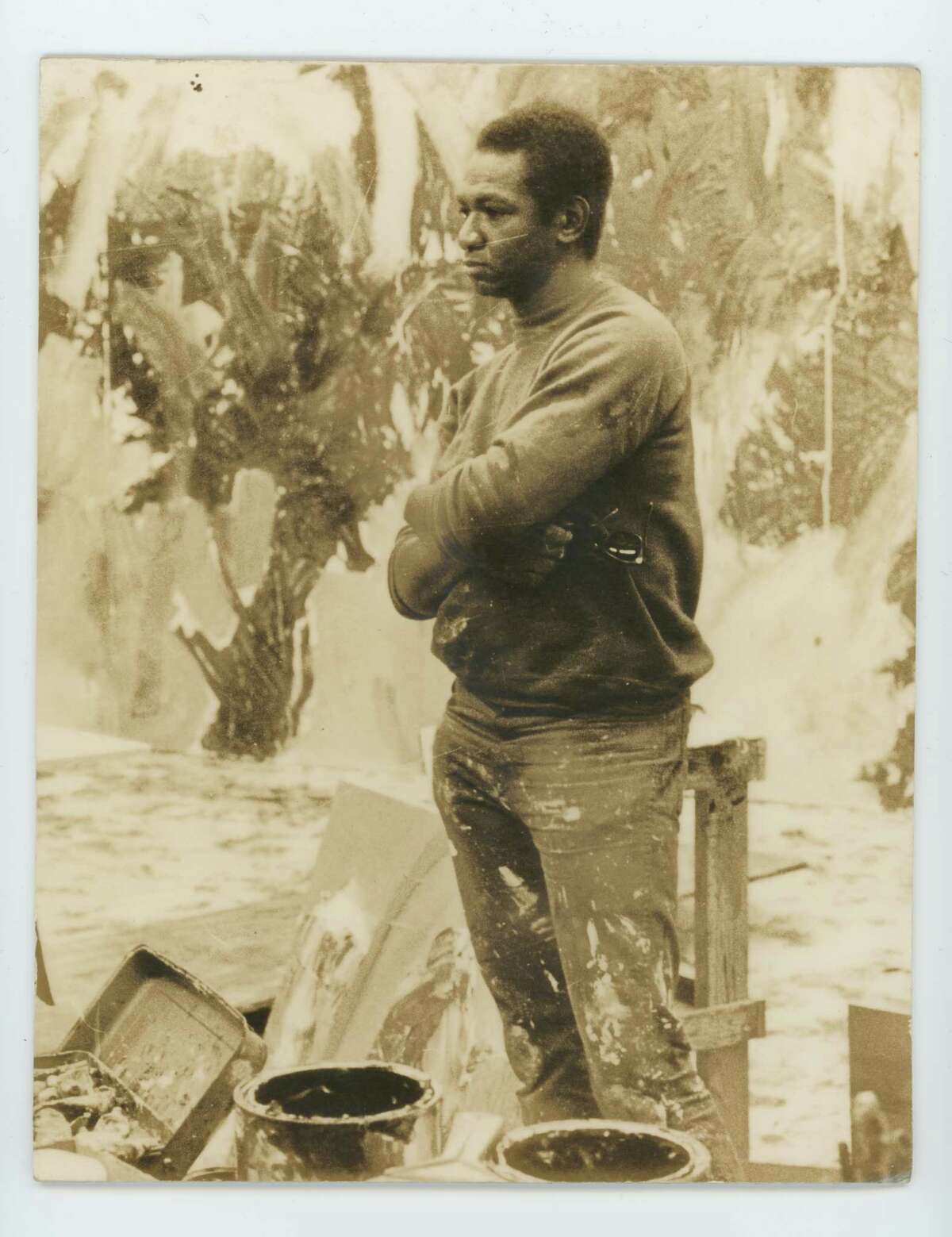

Mike Henderson poses in his art studio in San Leandro, Calif. on Monday, June 12, 2023. (Samantha Laurey / Special to The Chronicle)

Samantha Laurey/Special to The ChronicleMike Henderson believes in moving forward. Throughout his 50-plus years creating art, he’s been driven by what he calls “the great question: Why am I here?”

That purpose has also enabled him to work through devastating events, like the 1985 studio fire caused by a neighbor’s errant barbecue coal that decimated many of his groundbreaking protest paintings from the 1960s and ’70s.

The 80-year-old artist describes his first 20 years of work, which reflected the period’s cultural upheaval, as “a foundation I could stand on.” Much of that groundwork was “damaged somehow, either through the fire or rotted in storage,” he told The Chronicle via a video interview from his Oakland studio.

Decades later, his first major museum solo exhibition in 20 years, titled “Mike Henderson: Before the Fire, 1965-1985” and on view through July 15 at Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, has prompted the painter to look back at that tumultuous time. Now he sees how certain events, the fire most of all, steered him in a new direction.

“All of a sudden I start with a blank canvas again, and the material has to change because my life has changed,” he said.

Punctuated with his short films and blues music, which he’s played since the ’60s and continues to perform at Bay Area venues, the show features paintings that explore power and the radical Black politics of the ’60s and ’70s for a “profoundly moving and timely exhibition,” said Rachel Teagle, the museum’s founding director, in a statement. Some canvas edges are tattered and slightly scorched, either as a result of the 1985 blaze or from his own experimentation with the element, a practice that predated the accident.

The process to restore Henderson’s paintings began more than three years ago, a collaborative effort between Manetti Shrem’s curatorial team and the Oakland firm Preservation Arts with the support of Haines Gallery, which has represented Henderson since 1991. Through a process of “investigating the condition of paintings and developing treatment plans” like organic remediation, in-painting and re-stretching works, they were able to conserve 10 works for the monumental exhibition, said Robin Bernhard, director of collections and conservation at Preservation Arts.

The first room, themed “The Question of Violence,” drops the viewer into a turbulent flurry of racialized violence not dissimilar to our current moment. In the giant oil composition “Non-Violence,” the most visceral in the protest series, a white police officer brutalizes two Black people in their own home during the Civil Rights Movement era; off to the side, a ghoulish figure feasts on a human arm at the kitchen table. Though the painting is dark and pitched in shadows, its emotionally charged colors and kinetic impasto lend the image an unflinching clarity.

At the time, protests were a relatively new phenomenon for Henderson, who in 1965 moved from his quiet Missouri hometown of Marshall to the politically active streets of San Francisco. He attended the San Francisco Art Institute, one of the only desegregated art schools at the time, and for years had a studio in North Beach.

“I was witnessing something I’d never seen before,” he said, describing a Black Panther rally he attended in the mid-’60s. “It was exciting to be in a group of people who felt that the world could be better. … I grew up, if you weren’t saluting the flag or something like that and into football and Jesus, then, you know, there’s something wrong with you.”

Facing civil rights issues through his art — painting the terror he witnessed and the taboos of the time — helped dissolve the knots in his stomach, he said: “Every artist that I sort of admired through history and time has addressed the two main issues: death and violence.” He cites van Gogh’s “The Potato Eaters” as inspiration, along with several other greats who addressed “human concern.”

Henderson explored other cultural concerns like women’s issues, but those works, he said, were rotted beyond repair in a long-dormant storage container. Years later, he chooses “not to look back,” he said, comparing it to the ritual of hanging a photo of a deceased loved one in a casket.

Still, he added, being forced to look back was cathartic.

“Doing this catalog for the show was very interesting, to allow the emotional things I would go through, reliving all of that,” he said. “I’m looking forward to seeing how that opened my eyes. It definitely shows you what a brief thing life is, when you look at your life, say, from the middle to the end.”

Mike Henderson, “Self Portrait,” 1966. Acrylic on canvas, 45 × 29 inches. Collection of John and Gina Wasson.

Mike HendersonAt Manetti Shrem, Henderson’s “Self Making” room is covered in self-portraits. Some are figurative, like the 1966 “Self Portrait” where a hat casts a shadow over closed eyes as he sings or shouts. Other, more opaque, pieces gesture toward a mutable inner life, like the cosmic shapes and dysmorphic images in “Trust” (1981) that coalesce into a collage resembling a memory or dream.

Other rooms play his films from the 1970s, shorts in which Henderson narrates in flare dungarees against a San Francisco skyline, or dances in a kitchen with a touch of verite. A section that depicts spiritual motifs questions how power appears in biblical tales, sometimes reconfiguring them with his own subversive storytelling. The final room corrals the viewer into a soothing space that plays the artist’s blues music. A message on the wall encourages you to release and decompress through journaling or discussion after the intensity of the exhibition.

Reflecting on his work, Henderson has a way of connecting each creative stage with a particular phase of life. The fire was one reason for his shift away from protest paintings toward abstraction, but there was also his divestment in figurative work and the deliberate choices it requires. “After a while there, there was no more,” he said, regarding the protest motif. “I felt like I was repeating myself.”

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

From Mike Henderson’s “Pitchfork and the Devil,” 1979, color and black and white 16mm film, running time 15 minutes.

His mediums and materials, too, have evolved. He likens his chosen medium of oil paint to having a favorite instrument — for him, the guitar. His environment in the ’70s dictated a move to experimentation with acrylic. That, he said, sometimes felt like trying the drums, which he would have liked to play but made him feel like he “had two left feet.”

Changes in studio space forced changes in thinking. “Not having the big workspace that we did when we were going to school, the luxury of it all, all of a sudden you’ve got to deal with storage,” he said. “So the work changed.”

Mike Henderson (center) with Terry Allan (left) and William T. Wiley at their three-person show at Cuesta College Art Gallery in San Luis Obispo in 1988

Provided by Mike Henderson/Haines GalleryWhen the fire occurred in October 1985, Henderson was out of the country on a three-month tour in Europe. He wasn’t able to jet back and deal with it immediately because of the financial investment in the tour.

Once he returned to San Francisco, he moved to a less expensive artist warehouse in Oakland. His East Bay studio faced a back alley where new sounds — a church choir, songbirds, different languages — and views stimulated his senses. He immediately returned to oil and also accepted a full-time position at UC Davis, where he taught painting, filmmaking and printmaking for 43 years before retiring in 2012.

Mike Henderson pictured in his backyard garden in San Leandro.

Samantha Laurey/Special to The Chronicle“Eventually I realized the advantages of that,” he said. “Whatever the fire, the door it closed, it opened up another one.”

Life’s hedges and occasional flare-ups may be out of his control, the artist has learned, but one thing he can count on is the journey, and his desire to keep moving forward. He points to a book, “Beginner’s Mind, Zen Mind,” gifted to him by a fellow artist. “There was a passage, and it said: ‘Don’t worry about where the tracks are going, just enjoy the ride.’ ”

Reach Vanessa Labi:

Correction: This story has been updated to include Haines Gallery’s role in the restoration of Henderson’s work, and to make clear that San Francisco Art Institute was not the only desegregated art school at the time.