https://arth.sas.upenn.edu/news/huey-copeland-cover-artforum-october-2023

Huey Copeland on the cover of Artforum (October 2023)

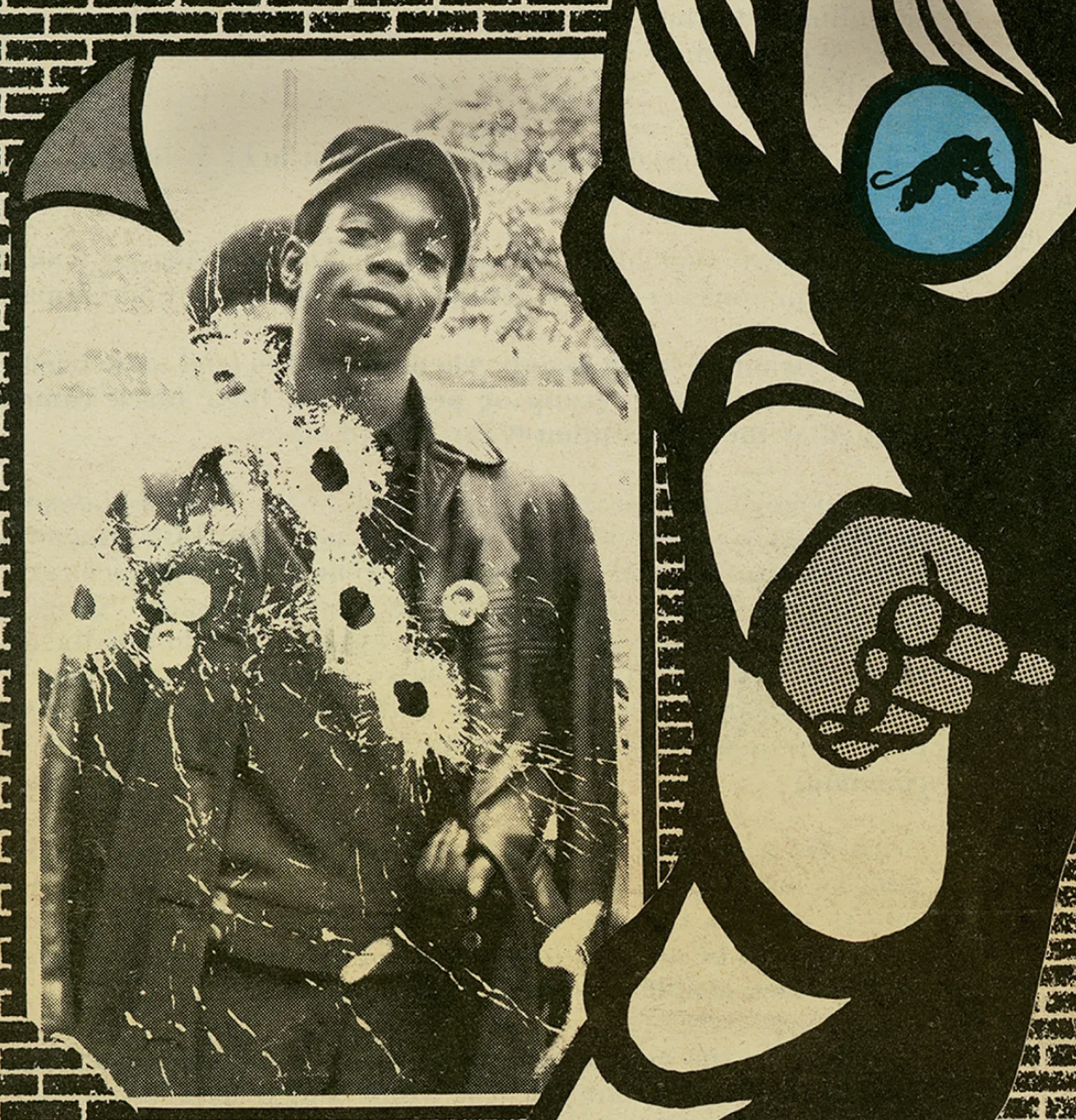

Detail of Emory Douglas’s back cover for The Black Panther, April 3, 1971. Bobby Hutton. © Emory Douglas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Professor Huey Copeland’s conversation is featured on the cover of the October issue of Artforum.

October 2, 2023

Let's Ride: Art history after Black studies

by Huey Copeland, Sampada Aranke, and Faye R. Gleisser

October 2023 | Artforum

BLACK STUDIES—as modeled by the transdisciplinary work of contemporary thinkers such as Kimberlé Crenshaw, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Saidiya Hartman, Kara Keeling, Katherine McKittrick, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, and Frank B. Wilderson III—has grown increasingly central to critical thought in the art world and the academy, with especially urgent implications for art-historical praxis: How do the discipline’s notions of objecthood and objectivity shift in light of transatlantic slavery’s production of persons as property? How must art-historical methods, given their origins in racist, sexist, and colonialist epistemologies, be retooled to engage with complexities of Black life and expression that are designed to evade capture? What becomes of art history as an intellectual enterprise when the ethical imperatives and liberatory horizons of Black studies occasion an interrogation of both the discipline’s objects of analysis and its political imaginaries? This year marks the publication of two groundbreaking books that address these questions.

Click HERE to read the entire article:

LET’S RIDE

BLACK STUDIES—as modeled by the transdisciplinary work of contemporary thinkers such as Kimberlé Crenshaw, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Saidiya Hartman, Kara Keeling, Katherine McKittrick, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, and Frank B. Wilderson III—has grown increasingly central to critical thought in the art world and the academy, with especially urgent implications for art-historical praxis: How do the discipline’s notions of objecthood and objectivity shift in light of transatlantic slavery’s production of persons as property? How must art-historical methods, given their origins in racist, sexist, and colonialist epistemologies, be retooled to engage with complexities of Black life and expression that are designed to evade capture? What becomes of art history as an intellectual enterprise when the ethical imperatives and liberatory horizons of Black studies occasion an interrogation of both the discipline’s objects of analysis and its political imaginaries? This year marks the publication of two groundbreaking books that address these questions.

In Death’s Futurity: The Visual Life of Black Power, Sampada Aranke provides a lyrical and materially nuanced account of how the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense mobilized a range of visual media, objects, and tactics to commemorate the tragic deaths and extend the revolutionary lives of three assassinated party leaders: Fred Hampton Jr., Bobby Hutton, and George Jackson. In the process, Aranke not only reorients our understanding of “the political” in art of the 1960s, but also puts tremendous pressure on art-historical conceits such as “the curatorial,” which in the Panthers’ hands does not mean protecting priceless artworks within neoliberal institutions, but rather involves preserving the bloodstained objects left in Hampton’s apartment in order to make visible the anti-Black violence that enables the coherence of American “civil society” and the ongoing expansion of the carceral state undergirding it.

A similar set of investments animates Faye R. Gleisser’s Risk Work: Making Art and Guerrilla Tactics in Punitive America, 1967–1987, which takes a complementary tack by homing in on the social reproduction of white supremacy and its import for art-historical inquiry. Organized around a diverse cast of Conceptual and performance artists and collectives, the book tells the riveting story of how US-based practitioners working in the shadow of the third-world guerrilla adapted themselves and their tactics to a nation increasingly reliant upon the prison-industrial complex, among other modes of racialized enclosure. Key to these efforts, and to Gleisser’s framing of them, is the notion of “punitive literacy,” which she defines as “the cumulative knowledge that allows for self-protective mobility in a penal society. It is a calculus of risk based on the body, spaces, and networks one inhabits. . . . Broadly speaking, punitive literacy is the ability to assess how one’s body will, or will not be, subjected to state violence.”

Taken together, these books’ foregrounding of Black radical histories and hermeneutics helps to model the discipline’s intersectional paths forward and enrich the African-American art historian’s methodological toolbox. Just as important, they set a rigorous standard for further work that moves beyond opportunistic engagements with African/diasporic art, whether produced by art historians with purposefully delimited understandings of Black culture or by cultural theorists with only a glancing familiarity with the aesthetic and the racialized historicity of its conventions. Here, contributing editor Huey Copeland, author of Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America, speaks with fellow travelers Aranke and Gleisser about their books as well as about the impact of Black studies on their scholarly and pedagogical practices, both present and future.

HUEY COPELAND: First off, I want to thank you both for these important interventions, which radically reframe our understanding of American visual culture post-1967—both its objects and histories as well as its figures and structural considerations. I think this is in no small part because of your projects’ sustained engagements with Black studies, which is still a relatively rare phenomenon within art history.

I had the privilege of seeing these books at earlier stages, and I wonder how, in bringing them into the world, you thought about negotiating both the demands of the art-historical discipline—the container in which we operate, departmentally and discursively—and the ethical imperatives of Black study, in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s sense, which push against and want to rupture precisely those kinds of disciplinary frameworks?

FAYE R. GLEISSER: Thank you for this invitation to be in conversation, Huey. It’s really such an honor. I’m thinking about how the art-historical discipline traditionally assigns value to arguments. I’m thinking about how these arguments are expected to be steeped in visual evidence that relies on formal analysis and classifications that are observable. The discipline uses comparative frameworks, and it relies on chronology and linearity.

All these demands of art history are at odds with artists’ tactics that subvert institutional power and thwart legibility and knowability. And, really, the Black radical tradition has been absolutely necessary to thinking through the work of artists’ tactics. I think, in some ways, what has been most useful in this challenge to art history is that Black studies provides methods for thinking about the relationship between vulnerability and power and how it’s maintained and normalized under white-supremacist conditions that manufacture and legalize gendered and sexualized anti-Black precarity.

From Black studies, I’ve learned that the call is not to become an expert on these subjects but to literally find ways to survive and collectively dismantle these structures. This approach has been critical to helping me understand that art history doesn’t merely tell stories about artists and art. It’s really through its own structural insistence on chronology, comparison, and classification that it reproduces anti-Black and colonial power structures.

These power structures have been scrutinized in necessary ways by scholars like Fred Moten, who show us that it’s not just looking but looking away—that it’s a particular kind of looking within the “hegemony of the visual”—or Saidiya Hartman’s work on the violence of empathy under conditions and afterlives of slavery. Or the work and writing on Black livingness that Katherine McKittrick names as the“praxis” of Black subjectivity.

This arena of scholarship has been a real toolbox for thinking about the politics of risk-taking and its racialized and gendered conditions. And that’s really what I’ve been trying to do in this study of “risk work,” which wants to think about more than just the romanticization of individualism and radicalism that we typically see in art history. Because there’s the celebration of the Artist with a capital A and the individual and their agency, but there’s also this story about the racialized, gendered work of taking risks that’s completely left out of a white-centering art history, which reconsolidates power in the stories we tell about resistance and intervention because it leaves white supremacy and anti-Blackness unaddressed.

HC: Word.

SAMPADA ARANKE: I’m so grateful to Huey for convening us. It’s a dream come true for many reasons, but key among them is what Faye just dropped. I’m sitting here like, Finally. It’s just this renewed energy, Faye, to hear you talk about the discipline of art history from a place of seeing where it recapitulates the same violence that some of us are aiming to undo. We’re a generation of scholars who have had the joys of coming up from within that critique. That was our starting point, working with people who trailblazed that. Huey, you’re among them. Krista [Thompson]is among them. Fred and Frank Wilderson are among them. Saidiya. We are able to start our work where we do only because of the work that you all have done to create an environment for scholars like us to be able to say brilliant things like what Faye just dropped unequivocally and without any fear or trepidation.

I feel like I can exhale, like, OK, we’re within our people. Which is such a big part of the work of Black studies: It forms and informs where you’re able to start a sentence. I call myself a bad art historian. I don’t have an art-history degree. My degree is in performance studies, so I feel like I’m on this strange path. And it’s because of people like Huey, who are like, “Come, find shelter in this section of the discipline that is a refuge for people invested in the things that aesthetics can make outside the burdens of market value, outside the teleological inheritance that Faye’s talking about, the construction of agency along racial vectors that don’t fit most of us.”

For me, the other piece that is so generative for the project—and just for the way that I think about what art can do—is how Blackness helps us rethink the intersection between objects and objecthood. Not only as a site of the production of extreme violence in the way that [Frantz] Fanon describes, but also in the uncanny way in which the aesthetic object is somehow constructed with Blackness always already in mind. There’s this fork in the road: You can—and we should—think about the extreme violence this mandates. And it also creates the opportunity to think about Blackness as an aesthetic formation that produces other forms that are both attached and unattached to a fixed or essential subjectivity.

Another way to put it is Blackness as a field, Blackness as a formation that almost turns upside down whiteness as the standard. That is a project, or maybe a language, that Black studies has given us and that I don’t take for granted. It still makes heads turn if you’re coming from a space so beautifully detailed, an idea of the aesthetic or an idea of objecthood that is bound to this white-supremacist ideal.

HC: It’s just amazing to hear both of you. What your accounts speak to, I think, is a fundamental shift in the temporal relation between Black studies and art history. I usually think of art history as belated in relation to Black studies—and to be honest, to many other things, methodologically! Folks like Moten and Hartman have been taken up in a broad way within the discipline only since, say, 2020, when they began to have more “mainstream” visibility and acclaim.

There are many folks now trying to wrap their heads around those discourses, and sometimes it happens to be in ways that at best misconstrue and at worst instrumentalize them as opposed to y’all, who have been deeply engaged with the work from the get-go. To me, that speaks to a different orientation in terms of what one wants the discipline to do because it has a much broader horizon of ethical and political commitments.

That brings me to a second question. Your books share a lot in terms of period and praxis—particularly their move away from singular artistic actors—and I think, importantly, your insistence on framing the American project as a carceral one, particularly as articulated for both of you by the work of Ruth Wilson Gilmore. But your interventions do differ in emphasis. To put it in baldly reductive terms, in Death’s Futurity, the project, it seems, is to understand the aesthetics of Black Panther politics as a revolutionary response to state violence. While Risk Work, we could say, reframes Conceptual and performance artists in relation to the ongoing production and reproduction of that same violence.

I’m hoping that you each might speak about how the aesthetic, the political, and their complex relation get recast in these books and about the implications for future studies not only of this period but of American art and contemporary art more broadly.

SA: Faye, I can’t wait to dig into this with you, because I feel like what you’re helping me do, in the aftermath of Death’s Futurity, is reconfigure the impact of the carceral in retrospect.I was so focused on the book being a microhistory. There are so many books on the Panthers. I just wanted this to be a trailer that I could hitch as a little addendum to something like Leigh Raiford’s Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare [2011] or [Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr.’s] Black Against Empire [2013].

One thing that I was really moved by when doing research is the way that the visual has always been constituted within the logic of the political. And because of that, the idea that the aesthetic is something that can be unbounded from the political imperatives of the mandate to be Black and live while there is an ongoing war against you—that, somehow, an aesthetic thing would be extra or abundant in relation to that—was completely false, (a), but (b), it’s also a misunderstanding of the political, which always mandates the formation of an aesthetic wing, whether that’s ideological or material or visual. It’s always already constituted within the logic of what it means to live in a world that is constantly out to kill you.

One of the things that really struck me was the way that documentary photography and documentary film were the technological apparatuses by which these aesthetic objects formed. That’s not because drawing or painting wasn’t happening. It’s because, within the logic of photographic technology, there is this relationship to capture, to fugitivity, to the ways that the history of the photographic is always dependent on anti-Black violence. It’s impossible for us to untether the things that apparatus makes, the way that apparatus gets perfected, for example, through Louis Agassiz and J. T. Zealy’s use of enslaved peoples in their experiments in daguerreotype, through these histories of extreme violence. It’s impossible for us to think about what those things produced, their aesthetic accumulations, as somehow separate from the politics from which they form. And because of that, Black radicals of the time turn to those very mechanisms, with their roots in anti-Black violence, to generate another form of resistance, rebellion, revolutionary existence.

I was committed to this idea of one story and one object, but it was so incredible to read your project, Faye, and all the multiplicities that it created for me in terms of recasting the entanglements of politics and aesthetics in the very same moment that my book is trying to unpack.

“It’s really through art history’s structural insistence on chronology, comparison, and classification that it reproduces anti-Black and colonial power structures.” —Faye R. Gleiss

FRG: That gives me so much to think about, and I loved reading your book. One of the reasons I’m excited to teach it is because it models this intentional closeness with following the mutations of images or the different contexts in which they accrue these important instances of resistance. But you really have to be looking for it, and your transparency about letting the objects lead, not covering up those gaps or those “imperfections” of the chronologies—what that’s teaching us is really powerful.

In my project, one of the things that came out was this desire to stay close to the centrality of the carceral within art history, how art history as a form reproduces carcerality through the ways that the discipline hasn’t adequately engaged with surveillance, violence, and force. It’s not ancillary to performance art, to Conceptual art, especially the artists I’m looking at, like Adrian Piper, Tehching Hsieh, and Pope.L and the groups PESTS, the Guerrilla Girls, and Asco, among others. They are anticipating arrest or the presence of police, and not as an afterthought. But that’s often how it’s talked about in art history when the police are mentioned anecdotally: “An artist did this thing in public, and then a police officer showed up and halted the piece.” That’s unsatisfactory; it discounts how artists differently anticipated that there would be police there and choreographed their movement and its documentation accordingly. Pope.L, for example, crawled through Times Square, a small space that was nevertheless one of the most heavily policed areas in all of New York City at that time.

Not looking away from the carceral is what allowed the naming of “punitive literacy” to come through in the book. In the United States, we have a lot of conversations around literacy. We talk about media literacy, financial literacy, cultural literacy, legal literacy. But becoming aware of how punitive relations shape our decisions to move, to act—how each of us is differently positioned, differently vulnerable to state-sanctioned violence—is a literacy, too. Artists who are thinking about form and aesthetics are great theorists of punitive literacy because within the guerrilla tactics they deploy in public, they are not only anticipating arrest but simultaneously theorizing how mobility, visuality, and materiality align within this reality.

I think of when Harry Gamboa Jr., one of the cofounders of Asco, spoke about anticipating police presence in East Los Angeles and needing to enact and document performance-based works on the street very quickly. He said you just have to be in a place for “a thousandth of a second” to take the photograph. I’m interested in how an image like First Supper (After a Major Riot) [1974] materializes this kind of temporality of being there and surviving punitiveness. And how the punitive temporality that informs Asco’s occupation of space is linked directly and dialectically to the timing of what Chris Burden is doing in the same city but in the gallery district, with a piece like Deadman [1972], where he feels comfortable lighting flares on the street and expecting them to last the full fifteen minutes he needs to perform. And he is shocked when police officers come and actually arrest him on charges of a false emergency being called in.

Those temporalities, those literacies, and punitive relations are linked. They are a form within the work. It’s not an ancillary aesthetic. And that’s also a politics of enablement, one that reveals, for example, Burden’s relationship as a white man to assumed protections under the law and the underpolicing that occurs in predominantly white, upper-class, English-speaking areas and neighborhoods. The book is thinking, too, about how artists’ punitive literacies are specific to the places where these artworks are happening in the United States, yet this is also a much larger story because policing is global. The United States plays a massive part in the manufacture of weaponry and the training and enhancement of militarized police violence worldwide. These relations shape art and its interpretation but have not yet been adequately named. We’re seeing a necessary, emergent critical vocabulary change art history now—thanks in no small part to methods of inquiry rooted in Black studies—with concepts like Nicole Fleetwood’s “carceral aesthetics” and Simone Browne’s “dark sousveillance.”

“Within the logic of photographic technology, there is this relationship to capture, to fugitivity, to the ways that the history of the photographic is always dependent on anti-Black violence.” —Sampada Aranke

SA: Hearing you talk about Pope.L, Gamboa, and Burden so brilliantly teases out how we think about the artist as a social formation. So often, we have to turn to the biographical to make our case.But your work posits a different matrix of formation, which is organized specifically around these structural realities like place, policing, the temporal registers of whatever medium is at play. And then it allows us to make the case for the way that the artist’s subject is formed precisely, maybe even primarily, through their relationship to the carceral versus the way that the carceral is embedded in their life story.

There’s a way, for example, that with the Pope.L crawl pieces, people turn to his relationship to being houseless, or his relationship to poverty, and the proximity of his life story to those systems. It is directional: from the singular person out. But you help us think about the structures that give rise to moments of artistic subjectivity instead of the ways that artistic subjectivity points to structures. I’m blown away that you’re able to get us to a nonessential, maybe even anti-essential notion of artistic subjectivity.

HC: Both projects are so smart in how they emphasize these fields of relation and how different actors can and cannot move within them—clearly, the lessons of performance studies have served you both well! Faye, you have this notion of interlacement, which I found incredibly compelling.I would love it if y’all could speak about the process of constructing a method that allows you to produce these narratives, which have different frames of reference and different understandings of what the individual artistic actor is and is not in relation to a wider constellation of possibilities.

FRG: I love writing, but it was really a struggle to write this book. Along the way, I got feedback saying that this wasn’t “art history.” I would get excited, like, “Why isn’t it art history? What are the narratives in place that suggest that we should limit our understanding of knowledge production and artistic practice?” But on the other hand, there is something about the book format that feels antagonistic to the story of artists’ tactics. Especially an art-history book, which is often based on these expectations of “high quality” visual documentation.Some of the images I’m working with don’t exist. Or they’re black-and-white, they’re grainy; they get swept up in the complications of collectives working together around possession and authorship and property rights.So the writing of the book just continued to reveal these larger power structures in which it is trapped or conditioned.

One of the ways that the writing of the book came together was through curation, and one of the earliest experiments with this question of literacy as a constructed condition was through a show called “The Making of a Fugitive” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2016. An inspiration for the show was a 1970 cover image of Life magazine that features Angela Davis; the title of the story was “The Making of a Fugitive.” I remember noticing how, in this dramatically cropped, blown-up image of her on the cover, another story in the magazine hovers nearby: “The Sculpture of Matisse.” And just sitting and looking at this cover, I realized I was seeing a composite image, an object lesson in the entanglement of power and form, wherein the making of a fugitive and the making of sculpture are cultural processes codetermined by racialized, gendered, and sexualized notions of innocence, beauty, and deviance. That cover, to me, is a case study in what you were saying earlier, Sam: The aesthetic and the political are deeply imbricated.

In that exhibition, I was thinking alongside artists like Glenn Ligon and Burden, Hương Ngô and Xaviera Simmons, looking at how we learn to know what fugitivity is or how that form takes shape in art history, in a museum collection. The writing is in some ways belated to the story that needs to be told. I don’t think necessarily that the book format is the best one for a history of guerrilla tactics, but I see the importance of writing it down on at the scale of a book alongside exhibitions and documentaries. It feels like a very cinematic story because it’s in motion, so I’ve struggled with the writing of it, and I think the interlacement is thinking about artists relationally but also the sites of knowledge production: archives, museums, police headquarters. Thinking about how art-history archives are also archives of policing and about how police archives are archives of art history. Interlacement was a strategy for thinking about those interconnections, those entanglements, as consistently as possible.

“The story of American art is a story of racial formation, and if you’re not willing to tell the story in that way or see it on its own terms, that’s not my problem.” —Sampada Aranke

SA: My first response to the question of method is the question of urgency, which I think is actually related to Faye. When you conduct this kind of research, be it archival or institutional, you’re returning to scenes that arose out of necessity.In the immediate aftermath of the murders of Bobby Hutton, Fred Hampton [Jr.], and George Jackson, there was this sense of a state of emergency. We were at war, and so we needed to create opportunities and occasions for the visual to help us fight that war.Which is already a different temporal register than conventions of art history, which assume that art comes after the war it’s about because it takes five years to make that painting about a war.

When you’re a historian decades out looking at this particular moment, if you’re doing it with a certain kind of attention, that urgency makes its way through. Then there’s the second layer, writing with that same urgency, by which I don’t mean doing it quickly, but holding on—in method or in voice or in form—to the fact that the scenes you’re turning to were responsive, that they had a certain political or ethical weight.

When it came to thinking about method, I also tried to think about how to tell the story through the object instead of through the ecosystem from which the object might appear for a few sentences or a few sections and then trail back off. I tried to hold on to the same urgency with which those objects were created, by letting the objects be the thing that propelled the narrative or that guided me through these other arenas. I wanted to tell the story of the object.

HC: I wanted to ask about the archive. Your frames of address are radically interdisciplinary, engaging the best of all these different fields, but you have really different means of expanding and critiquing the archive—both its violence and its silences, which, of course, have been a major preoccupation of scholars like Saidiya and Krista. How have your approaches to the archive evolved over the course of research and writing in relation to the specific material, political, and ethical concerns unique to each study and in the stories you wanted to tell about them?

FRG: I’ll start by saying that I really was in awe, Sam, of your work with the archive and your ability to name your own struggle with what you called “archival chasing,” this desire to find these stories, and then describing coming up short and really understanding that that is a big part of the story. Early on in this research, I wanted to write about Asco’s Decoy Gang War Victim, a significant media intervention in the ’70s, during which the artists created a staged image of gang-war aftermath that ended up on the local news as an authentic depiction of violence. It’s usually dated 1974. I wanted to find the footage of the news program that the artists had disrupted with their media hoax. So I went to UCLA, to the Film & Television Archive, and searched news programs from that year, but I couldn’t find the footage. What I found instead, as I continued to research this piece in exhibition catalogues, articles, and the artists’ archival papers, was that Decoy has been given many different dates: ’74, ’75, ’76, ’78. It jumps around, and initially I was like, How do I write about this act of sabotage if I can’t find it? Then I realized that’s what’s guerrilla. It’s fugitive within the archive, and what I’m seeing is the duration of its own misinformation as it’s moving around.

That was a turning point in my thinking about what the archives are when it comes to the story of guerrilla tactics in art. The other turning point was when I began to understand the long-lasting significance of when artists solicit arrest and when they evade arrest. For example, Pope.L evaded arrest in Times Square Crawl [1978] because crawling isn’t technically illegal. Because, as he says, “I wasn’t loitering, I was actually moving.” That is punitive literacy. He’s moving in a particular way that draws attention to these structures of legality around mobility. But his evasion of arrest is a present absence in legal discourse, one that impacts future court rulings: His non-arrest is not covered in studies of art and law. Instead, you start to see arrests of white men like Burden and Jean Toche, who are differently enabled and protected by police, become fundamental case studies for the emergent art law that is developing out of Stanford [University] in the mid-to-late 1970s. Those instances of punitive encounter become standards that set legal precedents around risk-taking in art, and they’re almost entirely shaped by the arrests and acquittals of white men.

I now have different questions about what is actually being constituted in art archives. I have interviewed artists who have recently evaded arrest while making performance art in public. The book’s epilogue considers today’s expanding carceral environment, and it became clear that I couldn’t include some of these examples. It was important to avoid bringing renewed and potentially harmful legal scrutiny to [these artists’] actions. That turns into another question of just how much of art history or these archives is shaped by the ability and necessity of people differently vulnerable to state-sanctioned violence to evade the historical record. What is the ethical imperative to talk about that shape in the archive, that shadow archive of non-arrest and what it does by remaining illegible?

Sam, you do such an amazing job of staying with those moments of not knowing. It’s so easy to retroactively think about what we know now—the proof of [the illegal FBI project] COINTELPRO, for example. You keep us in that moment of the archive, of exactly when and why the Black Panthers needed to create evidence of the state-sanctioned murders before this information was publicly accessible, and it’s really incisive.

SA: I feel so seen right now. I too, Faye, have images and stories that didn’t appear in the book because they weren’t mine to tell. Kara Keeling in The Witch’s Flight [2007] I think embodies this spirit so beautifully. Reading that book taught me the importance of trying not to betray the very thing that you want to live.

Certain archives were not meant to live; some objects in the book were meant to die. They were just supposed to be conduits to make the revolution happen, and then we wouldn’t need political posters or documentary films like this. They were cheaply made because they were popular objects and they were supposed to be accessible and democratic with a lowercase d, and they were stuffed in folders and pinned on walls, and they weren’t archival pigment. For me, trying to approach those objects in their livingness, in the ways that they were meant to be used, was fundamental.

I think you and I have this in common, Faye. We keep talking about artists. I’ve taught in art schools for ten years, and I want artists to be able to use this book. And I hope that they use these objects to make other histories so that there isn’t a unified consensus.

HC: I’m really interested in how these projects have shifted your pedagogical practices, above all in terms of what it means to narrate the story of American art or contemporary art. What does it even mean to tell the story of American artists? Do we care about Robert Smithson anymore? Or do we care about him because of Hotel Palenque [1969–72] instead of Spiral Jetty [1970]?

“We talk about media literacy, financial literacy, cultural literacy, legal literacy. But becoming aware of how punitive relations shape our decisions to move, to act—how each of us is differently positioned, differently vulnerable to state-sanctioned violence—is a literacy, too.” —Faye R. Gleisser

FRG: I really love this question about pedagogy. I think of it in terms of the structures of art history, the visual-analysis paper, the exhibition project, the chronologies, and the comparisons that are the bedrock of the discipline, especially in these introductory classes. I’ve been trying to rethink pedagogical exercises that make sure we are having conversations in the classroom around constructions of power through the stories we tell about art. Something I’ve been implementing alongside visual-analysis assignments are wonderment exercises, where I invite students to sit and ask questions about artworks based on things they cannot know. To really show that the practice of sitting with and asking questions about what you don’t know is a skill, that it’s knowledge-producing, and that it could be the basis of art or a research project.

I’ve also shifted away from relying on the exhibition project, where we invite students to curate shows around a theme. Alongside that, I now like to assign acquisition reports. It might sound boring to them at first, but that’s the point: “If you think this is bureaucratic, that is where power and knowledge are reconsolidated and normalized.” They’re writing a proposal for why a museum should acquire work and what that would do long-term. This makes them aware that these proposals are what curators do at collecting institutions: They have to go in front of a board of trustees. I’m trying to demystify the romanticized version of art history and get them involved in recognizing how structures of authority and whiteness are reinforced and the histories they come from.

The other, I think bigger takeaway for me pedagogically is that teaching art history or American art or contemporary art is also about teaching advocacy and collaboration. I want students to see that they have a part to play right now in changing the way things are done and that there are tactics at their disposal. Some of the really exciting work has happened when I’ve understood my own internalizing of noncompensation. I remember having teachers say, “Go interview an artist. You’re a student, they’ll think it’s cute and they’ll talk to you (for free).” But there’s no follow-up about payment or talking about the ways that universities normalize noncompensation for artists and how this model hides and exacerbates class, gender, and racial hierarchies within economies of exchange. So I worked in my department to create a fund so that students get in the practice of raising money for artists. If they’re interviewing artists for one of their projects, they compensate them, and this has been incredible, seeing students understand that they are part of institutions, that universities are not neutral, and that they can be advocates. We can have conversations around these structures that normalize extractive power relations and think differently about access and accountability.

I also rely on and teach the work of curators who are attuned to these concerns, like Allison Glenn and her recent collaboration with Amy Sherald in creating a coacquisition of the painting by Sherald of Breonna Taylor. Shifting this idea of just one institution owning an object, what it means to even think about coacquisition or to really care for art objects and the lives of the people connected to them, opens alternative possibilities. I also teach Thea Quiray Tagle’s work on “relational curation.” Thea is centering the care of artists and their trust and needs and prioritizing that over an exhibition schedule or object maintenance.

SA: I wish I could take your class. When I teach certain kinds of intros to American art, I basically teach it as an intro to African American art. I always start with a lecture about the Middle Passage, turning upside down this idea that the making of the modern world is anything other than anti-Black at its core. If you start from there, it allows students to self-select if they want to be in that class, but it also clarifies certain stories in art history. Suddenly, Surrealism doesn’t become something that’s so psychedelic or about a flight of fancy. It becomes shaped by the horror of the transatlantic slave trade: “If that is what constitutes the real, then fuck.”

I’ve really been unabashed about this since writing the book: “I don’t tell the story in this way. I tell the story in this way.” From there, I fill in everybody in relation to Black American artists. Then maybe the story isn’t just Smithson; the story is Smithson in the wake of Benjamin Patterson or, more directly, Smithson in conjunction with Noah Purifoy or Thornton Dial. Those are the artists who tell the dominant story, and then other stories are positioned in relation to them.

That is absolutely an ideological argument I’m making, and I tell students that outright. But for me, it’s also fundamentally about naming, without fear, whiteness as an aesthetic formation and white supremacy as a vector of power. Blackness is an aesthetic formation that reflects something about white supremacy but is actually not primarily about that. It’s a very simple thing, just flipping it around so I don’t have to name the phenomenon of a certain story of American art as a story about a white canon or a white Western canon or a white male canon. It does that for me.

I’m disinterested in code-switching between being the African Americanist in the department and then having to do the service of these bigger classrooms and pretending to be a generalist. Instead, it’s just like, “This is what I do. If you would love for me to do it in this way, let’s ride.” The story of American art is a story of racial formation, and if you’re not willing to tell the story in that way or see it on its own terms, that’s not my problem.

HC: More and more, for the students I’m encountering, intersectionality is the floor. If you can’t speak to that analytic, they’re like, “Um . . . what are you talking about?” [Laughter.]

In closing, I want to ask, What is on the horizon for each of you? How does what you’re working on now extend, redirect, radically depart from, or build on the lessons you learned writing these books?

SA: Toward the end of my research, I started seeing the works of Black American artists who weren’t directly a part of the Black Panthers or weren’t even organizers in their own right but who were making works that were responsive to the same kinds of political events that the Panthers were responding to. Artists like Melvin Edwards and Benny Andrews and Faith Ringgold. That cracked open a whole turn that I’m hoping to take up in the second project, which is loosely called “The Hammons Effect.” It’s not about David Hammons, really, but about the ways that David Hammons presses on certain methodologies and conventions of contemporary art history that help us reconfigure the role of the Black American artist as we think about how to stage stories in an exhibition setting.

It may or may not be a book. But as of now, that project will look at artists, curators, and collectors who are impacted by methodological turns that Hammons himself performs to help us assemble modes of storytelling that fall out of some conventions. And, quite honestly, forms of policing, to your point, Faye, that art history mandates that we perform, which completely recapitulate the violences that we want to undo when we tell stories about Black arts and Black aesthetics.

FRG: I can’t wait to learn more about that project. Coming out of Risk Work, I’ve taken a turn toward embodiment that combines the sensorial, the haptic, and its relationship to racial formation. This new project is tentatively called “The Color of Hormones.” I’m going to be a research fellow at the Kinsey Institute and a College Arts and Humanities Institute research fellow at Indiana University in the fall, and I want to spend time in the archive thinking about and looking for material articulations of hormonal management and relations of hormones and perception.

Part of this research extends the interest in Risk Work around punitive literacy to the ongoing criminalizing of gestational bodies and surveillance of hormonal management. I’m looking to better understand the narration of hormones. Hormones, in the scientific sense, were “discovered” in the early twentieth century, but the story of hormones goes much farther back, obviously. I’m interested in the history of trying to know what happens inside our bodies and how this narration of hormones is also a history of how the desire to know has been enacted within a society that largely prioritizes visual evidence and documentation and criminalizes illegibility, nonlinearity, and nonnormative desires. I’ve been really influenced by the work of artist Elizabeth M. Claffey and her questions around hormonal consciousness and radical kinship and am looking to her and a number of artists investigating somatic knowledge.

This research is unfolding at a very particular moment. The Kinsey Institute [originally the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research] has been hosted at Indiana University since the late 1940s, and it’s always been under assault by conservative and religious groups because of the way it documents and celebrates and legitimizes human sexual desires. This past spring, Indiana State legislators banned the use of state funds to support the Kinsey. That’s become a very complicated event, with large implications for the existence and role of the Kinsey, and I think that will also be part of the story I’m tracing. It’s not just how hormones have been narrativized but how the archives or the sites for their study are increasingly policed.

HC: That’s fascinating! It’s interesting, too, because one of the things you say toward the end of your introduction is, “Look, this is a study that I realize is focused on people that are cis-gendered and heteronormative.” It seems like this new project is trying to sit more within that complicated space that wasn’t centered in Risk Work because of how the artists’ own identities and identifications informed their actions.

FRG: Thank you for mentioning that. That is definitely something I’ve been thinking about. In a lot of ways, Risk Work is about canon revision, and I think this next project is less invested in the canon as a structure to navigate. I’m drawn to the work that’s emerging in critical trans* and disability studies that is challenging rights-based or representationally based politics or modes of resistance. Hormones hopefully open up powerful modes of connection that resist this ocular-centric needing to see, needing to know. Because it’s impossible to adequately describe these internal hormonal experiences, and yet there is a desire to do that. I’m drawn to this tension.

HC: That so beautifully underlines how what animates

the work, for both of you and for us as readers, is that willingness to

sit with these impossible-to-narrate moments and to allow them to open

onto other sets of possibilities than the ones scripted for us. So thank you.