by Kofi Natambu

The Panopticon Review

The history of sound and the conscious (re)organization and structural manipulation of its elemental dimensions (which we culturally and socially designate and define as "music") is nothing less than the history of our very existence on this planet and is thus an integral part of the physical and metaphysical DNA of what constitutes our lives and living in all its guises. Immersed in consciously wrestling with the creative demands and environmental terrain of this sonic forcefield are fearless and innovative musicians and composers who seek to not only actively engage and register these sounds at the level of the aural (and oral) aspects of absorbing and (re)producing its multivaried reality, but creatively and intellectually challenge our conventional perceptions and ideas of what the canonical histories and ritual traditions of music making means to us and our various conceptions and understandings of how we jointly experience and express this shared inheritance at both the quotidian and cosmic levels of our human engagement with this larger reality we call "nature."

It is in that broader and all encompassing context that we encounter and experience the varying sounds offered us by musicians and composers who have mastered the art of critically and/or joyfully examining intricate nuances of these histories and traditions in ways that simultaneously embrace and yet go beyond known artistic genres and expressive styles into a new realm of knowing and being that requires our sonic and textural connection to 'other aspects' of ourselves that we may have neglected or simply taken for granted in the past. It is this gateway to our experience via sound and its endless reverberations that such profound and deeply attentive musicians and composers as Roscoe Mitchell (b. 1940) have made possible while remaining both loyal to and openly challenging what we have been told about what constitutes various musics throughout our known world. This total commitment to the entire range of generic and stylistic traditions in this world (from "Jazz" to "classical", "blues", "rhythm and blues", "rock" and many other different "folk" and "spiritual" forms). Thus what we find in Mitchell is a man and an artist who has over the past 50 years(!) been and remains a major leading force in the creative rise and expansion and influence of what presently constitutes improvised and composed ensemble music on both a national and global scale.

The Panopticon Review

The history of sound and the conscious (re)organization and structural manipulation of its elemental dimensions (which we culturally and socially designate and define as "music") is nothing less than the history of our very existence on this planet and is thus an integral part of the physical and metaphysical DNA of what constitutes our lives and living in all its guises. Immersed in consciously wrestling with the creative demands and environmental terrain of this sonic forcefield are fearless and innovative musicians and composers who seek to not only actively engage and register these sounds at the level of the aural (and oral) aspects of absorbing and (re)producing its multivaried reality, but creatively and intellectually challenge our conventional perceptions and ideas of what the canonical histories and ritual traditions of music making means to us and our various conceptions and understandings of how we jointly experience and express this shared inheritance at both the quotidian and cosmic levels of our human engagement with this larger reality we call "nature."

It is in that broader and all encompassing context that we encounter and experience the varying sounds offered us by musicians and composers who have mastered the art of critically and/or joyfully examining intricate nuances of these histories and traditions in ways that simultaneously embrace and yet go beyond known artistic genres and expressive styles into a new realm of knowing and being that requires our sonic and textural connection to 'other aspects' of ourselves that we may have neglected or simply taken for granted in the past. It is this gateway to our experience via sound and its endless reverberations that such profound and deeply attentive musicians and composers as Roscoe Mitchell (b. 1940) have made possible while remaining both loyal to and openly challenging what we have been told about what constitutes various musics throughout our known world. This total commitment to the entire range of generic and stylistic traditions in this world (from "Jazz" to "classical", "blues", "rhythm and blues", "rock" and many other different "folk" and "spiritual" forms). Thus what we find in Mitchell is a man and an artist who has over the past 50 years(!) been and remains a major leading force in the creative rise and expansion and influence of what presently constitutes improvised and composed ensemble music on both a national and global scale.

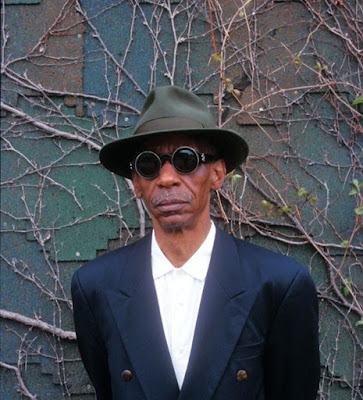

Roscoe Mitchell

(b. August 3, 1940)

Mr. Mitchell has recorded 87 albums and has written over 250 compositions. His compositions range from classical to contemporary, from wild and forceful free jazz to ornate chamber music. His instrumental expertise includes the saxophone family, from the sopranino to the bass saxophone; the recorder family, from sopranino to great bass recorder; flute, piccolo, clarinet, and the transverse flute.

His teaching credits include the University of Illinois, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the California Institute of the Arts, the AACM School of Music, the Creative Music Studio, The New England Conservatory Boston Masschusetts, University of Wisconsin Plattville, Wisconsin, Oberlin College Ohio and numerous workshops and artists-in-residence positions throughout the world. August 2007, Mr. Mitchell assumed the Darius Milhaud Chair at Mills College, Oakland, California.

Roscoe Mitchell

by Anthony Coleman

BOMB 91/Spring 2005

MUSIC

(Interview)

Roscoe Mitchell is one of the most important composer-improvisers of our time as well as a major musical thinker and conceptualist. His work has been important to my thinking since I became aware of it, over 30 years ago. He is certainly best known for his work with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, but I have a special fascination for two of the records he has released under his own name: Sound (Delmark, 1966) and Nonaah (Nessa, 1978). In addition to his mastery of the saxophone, he is an innovator in the use of collage techniques, repetition, silence, noise, and the AEC’s specialty “little instruments”: recorder, harmonica, whistle, and a range of small percussives like gourds and bells. Mitchell, along with his colleagues in the Chicago-based AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) particularly Anthony Braxton and Leo Smith, took the next step from the innovations of first-generation Free Jazz (Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor. Albert Ayler). The paroxysm or “ecstatic moment” that one finds in so much of early Free Jazz is channeled into a music which follows the stream of consciousness through a vastly different arc, one which relies much more on peaks and valleys. Where and how did this group of composer-performers grasp the necessity of this step? Although it has global implications, the jazz mainstream has never truly embraced it. On the fringes, however, this work has been extremely influential and I was delighted to have the chance to ask Roscoe Mitchell some of the questions that his music has raised for me.

Anthony Coleman So, I just got to hear the rehearsal of your new piece, “The Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City.” Where does the title come from? The text is from Joseph Jarman, is that right?

Roscoe Mitchell Yes, that’s correct, it’s from a poem he wrote. I became interested in setting it to music after doing a performance with Joseph reciting it back in the ’60s, A recording and videotape of that performance was originally made by Channel Four, the English channel. The videotape was later reissued by DIW/Art Ensemble.

AC It’s been very good for me to go back and listen to your records. You use radically different languages depending on projects. Some pieces are almost minimalist, with phrase repetition, and other pieces come much more clearly out of the jazz tradition. I’m thinking of the the Moers Creative Orchestra . . .

PM Well, that is true. All of these different aspects of music are great and you don’t want to be excluded from any of them, so the best thing in your studies is to look at all of these things. Talking about the Moers Creative Orchestra music, one piece on that album is a swing piece, there’s another one that is rather minimalist but that comes out of a system of cards that I developed. I was doing a lot of workshops with improvisers and I noticed that there were some common problems that most of these ensembles would have. So I went about trying to create something that would help people with these problems. The cards have music written on them and each musician gets six cards that they can arrange in any way that they want, at their own tempo, to create their own improvisation. You actually score the improvisation, thereby eliminating the musician having to come up with the material to play, which is one of the problems I’ve had in playing with inexperienced improvisers.

AC I noticed on Song For My Sister, you also have a piece that talks about the cards.

RM Yeah, that piece was also generated from the card catalogue.

AC Would you talk a little bit more about the problems of inexperienced improvisers? I played for a long time in John Zorn’s project Cobra, that’s not about inexperienced improvisers, but about the kinds of things improvisers do by rote. For example, improvisers tend to show that they’re listening by imitating what the other person’s playing. That can get to be an enormous cliché and in fact you can really show that you’re listening to people by doing something radically different from what they’re doing. Cobra sets up both situations.

RM Well, you actually hit on one of the problems. You’re doing the phrase and then someone else is coming up and doing it. That means that they’re not really there in the moment. They’re waiting around to listen to see what you’re doing. I would describe it like being behind on a written piece of music—you really know your part, and I don’t really know mine, so I’m kind of following and listening to see what you’re doing and because of that I can’t really be with you. That was one of the problems I wanted to correct, getting people to function as individuals inside of the improvisation so that counterpoint is maintained, which is a very important element in music. I also addressed the issue of people leaving some space of rest in between what they’re doing. You wouldn’t compose a piece that was a run-on sentence, but this is what a lot of inexperienced improvisers do. I introduce complex rhythmic figures so that everybody’s not always hitting on one all the time. You know, I bring them in at different parts of the beat—all of these things that you would have in a written piece of music.

AC You mentioned silence, AACM brought the use of silence to the world of black music or jazz as a very strong parameter. It’s something you and [Anthony] Braxton and Leo [Smith] all share in your music. When I listen to your record Sound, Braxton’s For Alto, and early Leo, the connections are so obvious and very deep. You’ve mentioned the concerts that you did together. Did you all talk about theories of silence or was it just understood that you had arrived at this moment together?

RM See, this is the difference between Chicago and New York. Musicians really got together and rehearsed in Chicago, over a long period, on a consistent basis. So all of these questions came up, and we were constantly trying to figure out how the improvisation related to each piece in the song. And we spent a lot of time developing improvisation for a particular piece. If you were to write a piece of music, you might have these instruments leading for a minute and then these over here and so on, and then some silent, and some playing at one point and then those instruments silent. So, it’s all those kinds of things. I feel like if you want to be a good improviser you have to know how composition works. Music is 50 percent sound and 50 percent silence. If you sit down and listen to nothing but silence, it’s very intense. So, when you interrupt that silence with a sound, then they start to work together, depending on how you use the space. I’ve practiced it in lots of different ways. A lot of younger improvisers will get into this rhythm that doesn’t exist, that they feel somehow committed to, and just pound away at that. I’ve found that these different card strategies can move you out of that and move you into an area where things start to become a bit more open.

AC Were you at all influenced by Cage?

RM Oh, we used to have concerts with Cage. In the early days, Joseph Jarman and John Cage would do performances together. See, this is the thing that we’ve gotten away from. Back then, you’d have concerts with a very wide palate musically; you were always listening to all these different people. Now people get involved in these narrow fads and that has really cut off a lot of their options, when in fact most of our listeners are accustomed to being challenged on several levels.

AC This may be a side question, but when you look at Cage’s statements on black music or jazz, they’re very, very limited. Was he present at these concerts?

RM Yeah, they were performing there. Though I wouldn’t call what they were doing jazz, either.

AC Right, but still, it should have given him some sort of idea that there were other possibilities in that language.

RM The impression that I got was that they were meeting as improvisers, and they were exploring from that end. I mean, John Cage would be hooked up to different microphones on his throat and he’d drink something, and so on. It didn’t really have any elements of jazz or rhythm in it.

AC So much of what the AACM was about, and so much of what the Art Ensemble was about was the distinctness of the personalities involved, the counterpoint between the personalities. Do you feel any kind of stylistic difference between your own music and the music that you’ve done within the Art Ensemble?

RM No. The way I see it, the Art Ensemble is like what you just said. It was a band of individuals who would go out and explore different things and bring in new ideas to the collective. It was a unit that studied music all the time and was constantly exploring different ways of doing music. Over the years, you develop this vocabulary that you can expand and extend. I can go back now and look at some of those concepts in a whole other kind of way that I couldn’t have done back then because I didn’t have the knowledge or the language to be able to do that. For instance, in the ’60s I heard these long lines at a rapid pace that never stopped. I couldn’t put those lines together then because I couldn’t circular breathe. But once I was able to, I could practice and perfect them. With me, everything is a study. If I’ve done something this way tonight, I’m trying to do that a little bit differently the next night, because the element of music that interests me is the exploration. I think I’ve probably said this before, but we’re living in the era of the Super Musician now; this is what I’m trying to be.

AC So you want to be able to fit into all of these contexts equally, with equal strength, equal passion.

RM Oh, that would be great. I can’t stand to hear somebody doing something that I really like and then I don’t know how to do it. And that’s part of the motivation.

AC What’s the thing you want to find out how to do now?

RM So much, man. I need another life! I definitely want to go back to working with the earlier instruments after I get off the road this time. I’ve already set up a bunch of rehearsals. I was really starting to get into the whole concept and improvisational aspect of it, playing with recorders, the baroque flute . . .

AC Do you listen to a lot of Renaissance music?

RM Oh yeah, definitely, and play it. We did a big concert in Madison where I took some existing pieces that we had and brought Joe Kubera and Thomas Buckner. Like I said, there’s a lot of stuff out there to learn. My fascination with the instruments is that the sound is so incredible.

AC I’m interested in all the different musical languages that you access. But when I think about your music, there are certain patterns that really come to me as your thing. If you look at Noonah, for example, there’s an obsessiveness that you’re able to access that seems to be yours. You don’t use it all the time, of course, but it’s in a certain relation to early minimalism, you know, minimalism before it became fun. (laughter)

RM Right. You know, there are different types of minimalism too. There’s a minimalism that deals with things rhythmically, there’s another type that deals with very few notes. The piece I’m working on right now is like that. It’s for this thing in Munich called Symposium in Munich, two weeks of music, lectures, demonstrations with myself and Evan Parker as the composers. We have a 12-piece ensemble and our concerts will be recorded by ECM. What I’m interested in with this piece is that it’s limited to a few notes but then when you put all these different rhythms together, that makes things react in a very strange way, all of these different sounds come out.

AC So the pitch field is set? How limited is it?

RM Three notes.

AC And then the rhythms are given? Or they are freely improvised?

RM No, I’m writing them down. There’ll be improvisation with the piece, but it’ll be on the improvisers to construct the improvisations according to what they have experienced in the piece. And I’ll probably suggest a few approaches for improvisation. There’ll be one section where each player has three notes. And then maybe I’ll work up a section where each player only has one note of the three, and then at the end of that, the selected player or players would be asked to do an improvisation with just that one note to see what they can really do with that one note.

AC I’m glad you still work in that way. It’s a part of your music that has always meant a lot to me. From the record Sound to Nonaah.

RM Well, it’s a constant study, what I find is that it just doesn’t stop. If you really want to develop yourself as an improviser, you have to do it that way. Sometimes you jump up there and can’t do any wrong, but most of the time music is work.

AC For sure. I was talking about the similarities between you and Leo and Braxton, how they never worked with those repetitive phrases. This is a kind of a personal question, but in the Art Ensemble did you ever find that your obsessive way of working was not well received? It’s very different from their music.

RM Well, see that’s the thing about the Art Ensemble. Nobody tried to tell anybody what to do. What I do is study extremes. So if you have the obsessive, you also have things that are not so obsessive.

AC But even in your bebop tunes, I’ve noticed sometimes, there’ll be a cycling of a couple of pitches, almost Monkish, or maybe even more connected to someone like Sonny Rollins’ playing, where a couple of notes are sort of worried or turned around, like in “Song for Atala.”

RM Oh, yeah, that’s the song I wrote for my daughter. That’s a little bit different format. Instead of being 8-8-8, and a bridge, it is an A-A-B-A but 16-16-8-16. A lot of my tunes have a twist in them like that. Like the “Ninth Room” is 9-9-9-9-9, it’s nine measures. It is, I guess, just trying to take something a little further or put a different twist on it. Actually, different forms for things are created, and so you either stick with that or you create yet another form.

AC There’s something I noticed around the end of the ’70s, where the Art Ensemble went from being more stream-of-consciousness, a big canvas where one kind of stylistic thing flowed into another, and became more like a catalogue. A Message to our Folks was a partitioned record from earlier, but as the late ’70s came along discrete pieces seemed to become the rule: the Roscoe piece, the Lester piece . . . How conscious was that?

RM I don’t know if it was a conscious thing. You know that as that era approached, everything was changing. The Art Ensemble was one of a very small number of groups that even survived the late ’70s. The music in general changed, in some ways it got a little more conservative, but thank God we’re coming to the end of that.

AC You think?

RM Yeah, I think we are, man.

AC I hope so. Do you see it from your touring?

RM In the touring, from students asking me different questions . . . A lot of them have gone to college, they come out and they’re disillusioned. A young trumpet player that I’m playing with now, Corey Wilkes, he goes out to sit in at a lot of jam sessions, the same thing that I used to do when I was young, and he’s getting tired of it. Everybody’s up there sounding the same or playing the same kind of a thing and it doesn’t have any meaning because they don’t really know what they’re doing. I mean it’s hard to think of a situation that doesn’t really exist anymore and try to relate that to something that’s really happening. But you can look at it in the sense of re-creation.

AC You think the idea of a jazz repertory orchestra is good thing?

RM Oh yeah, I think it is. But I don’t think it’s a good thing to say that they’re the only thing happening and nobody else is.

AC But the jazz repertory orchestra brings up a lot of questions. Like when you have the saxophone sound not being the right saxophone sound, then it’s not really—

RM —It’s not right.

AC But on the other hand, take an improviser, if they’re going to get themselves to be able to play with the saxophone sound of a Johnny Hodges, how creative can they be with it in terms of their own playing?

RM It’s hard, because if you look at the real-life stories, I mean, Bird used to listen to Lester Young. They don’t sound anything like each other. What I’ve noticed about the masters of the music is that it’s really music. It’s not mechanical in any sense of the word. They’re hearing ideas and bringing them about based on their lifestyles. This is what I think makes their music so important. I look at the saxophone as one of the most versatile instruments there is. There are so many people with so many different approaches to the saxophone; it’s a study. So you study these different styles. You think about the tenor, there are a lot of people to study there. It goes on and on. What I would say to a musician is this: That’s there for you to study, you take that, and then you bring your own thing to it, and that’s where your own message comes from.

AC Tell me a little about your approach to saxophone sound, especially on the tenor. You have a unique, very particular sound on the tenor. I could recognize you anywhere. Also on the alto, but on tenor you have this way of approaching articulation where you really put it in the face of the listener. I could say maybe it comes out of Rollins, but it’s still very much your own thing. Sometimes almost consciously not articulating. I know you’re a master of articulating. But sometimes you use the same articulation with a lot of notes in a row.

RM There I am at the extremes again. I’ll take a particular rhythm through all of its courses. That way you really do get familiar with it. But the tenor for me was problematic. I was always hearing it higher than what it is because I come from alto. And then with the alto I’d be trying to get a lower sound. But once I came to grips with what the sound of the tenor really was I think then I started to advance a little bit on it. If I’m playing the soprano, I’m trying to get it down low, so it doesn’t sound irritating. Those higher instruments, there’s a special skill in playing those to get them where they really sound warm. Now I’m starting to get a sound on the tenor that I can rely on. And that’s been a long time coming. What helped me with it was playing the bass saxophone because I could approach it the other way, and that helped put it in perspective.

AC Bass saxophone is really special.

RM Oh my God. I love it. It’s just so difficult to get around. And now, they make it so hard for you, like at the airports.

AC (laughter) What about this new piece that we just heard in rehearsal? It has a kind of tonal language that is surprising in a way. I guess I don’t know some of your other music that goes in that particular direction. It has something to do with the instruments, the way the voice is underscored. It’s a very attractive tonal language with a lot of diminished coloring. I’m curious about how you approached that. Having heard some of your earlier orchestral music, not particularly for symphony orchestra, but the Creative Orchestra music, it’s surprising.

RM What I’ve found working with text is to a certain degree the text dictates how the music should be. You can’t take a sad song and write a bunch of major stuff around it, so a lot of the time a text will inspire the way I approach it musically.

AC Have you written a lot of pieces that use musical language in this way?

RM For orchestra I have Variations and Sketches from the Bamboo Terrace and Fallen Heroes. Those are the largest works. But a lot of times the musical pieces develop over a long period. If you look at Variations and Sketches from the Bamboo Terrace, it started out as a piece for the trio space, Thomas Buckner, voice, Gerald Oshita, and myself on woodwinds. It eventually developed into a chamber orchestra piece that incorporated improvisation inside of it. A lot of my works start off with an initial idea that I may decide to continue later. After hearing the improvisation, I was inspired to extend and write some of it out. It has two parts for soloists in it, one for bass, which was inspired by an improvisational solo that Mel Graves played on this piece, and it also has a rather extended, written-out part for the violin. I wrote that after I wrote the bass solo, just in terms of the way I wanted to lay the piece out. It’s the voice, which is featured in “Variation Number 1” and then you move into the second part, which is “Sketches,” that features a solo for bass and a solo for violin, and then the last part is “Variations Number 2” which features the voice again.

AC I want to talk a little bit about the Note Factory. I’ve seen the Note Factory in concert a couple of times, I’ve heard the records, and its interesting, when you were talking about the Super Musician of today—people like Craig Taborn, Vijay Ayer, these are really the prime examples of what you’re describing.

RM Well, I would say that the Super Musician is concerned with the study of music, wherever it takes him. The Super Musician is someone that is able to move freely in and out of several musical genres. And that incorporates a lot. I see the Super Musician as someone who not only plays with an ensemble but who also does solo concerts. You have to know how to do that on your own and it helps you because it really teaches you how to function individually.

AC But if I think about the musicians of the ’70s, who were Super Musicians in their own way, but more quirky in a sense, they had one thing that they could do fantastically. Jarman is a genius, but I would never say that he was a Super Musician in the terms that you were talking about. His limitations, like some of the early greats such as Johnny Dodds or King Oliver, were so much a part of what made him who he was. If you listen to the early ’70s players, there was always a big edge on the sound. I find I’m not as drawn in by the Super Musician’s sound today as I have been by some people who maybe didn’t have as big a vocabulary.

RM Well, I think that’s what draws you in, the sound. I certainly get drawn in by the sound. If I hear Johnny Griffin, it’s the sound. If I hear Sonny Rollins, I’m drawn in. It’s the sound.

AC I’ve played with Gerald Cleaver, Craig Taborn. They have the ability to leap between the mainstream and the avant-garde with no trouble.

RM Yeah, I agree. But it’s still a long road. At some point I’m going to do a record of classical flute.

AC What repertoire would you want to play?

RM Well, I like all the great composers, like Bach and Beethoven. And I do concerts where I perform their music. I have a trio called the Nonaah trio for flute, bassoon, and piano that performs concerts regularly here in Madison.

AC Who’s the pianist?

RM Jim Erickson. And Willie Walters is the bassoonist. I’ve got a piece that I’m working on right now with a composer from Puerto Rico named William Ortiz for flute and guitar. Before I was on tour, Jaime Guiscafre and I were working on it rather consistently. William sent us the piece because he heard this recording of Jaime’s where I’m playing flute on some of the pieces, bossa novas, sambas and stuff like that, flute and guitar and so on. There’s a lot out there that I’m fascinated by. I figured the only way that you can really learn the flute is by taking it through the standard repertory to avoid becoming a saxophone player that just plays the flute on the side.

AC One of the most interesting things I’ve ever heard was when I asked John Zorn whether he considered himself a jazz musician. He said, “Listen, I play the classical music of the saxophone. And the classical music of the saxophone is Charlie Parker, Lester Young. If you learn the classical repertoire of the flute you have to learn Bach and so on, if you want to learn the classical music of the saxophone, it’s not going to be Jacques Ibert.” That’s not what has established the saxophone as a language.

RM But see, like, I’m interested also in Jacques Ibert. (laughter) I mean, all the tonguing and stuff in there, man.

AC Marcel Mule, you interested in Marcel Mule records?

RM Definitely. And Rudy Wiedoff.

AC Rudy Wiedoff is a very special case. Chicago also, right?

RM That’s right. Rudy Wiedoff had this tonguing thing happening. I have all his books. These pieces where he’s got the saxophone laughing. I love the saxophone, anybody that’s playing. I mean, I’m not crazy, I know whether or not somebody’s playing the saxophone!

AC Those guys were, definitely. I mean Lester Young adored Frankie Trumbauer. Whatever else you can say about them, they’re definitely playing the saxophone.

Roscoe Mitchell. Images: Roscoe Mitchell. Photos: Joseph Blough. Courtesy of the photographer.

Roscoe Mitchell Interview (3 of 3) - AACM

ALL COMPOSITIONS BY ROSCOE MITCHELL

William Winant (percussion): Jacob Zimmerman (alto saxophone); Dan VanHassel (piano); Eclipse Quartet; James Fei Alto Quartet; Thomas Buckner (baritone); Petr Kotik (conductor)

A monumental recording of recent concert works by Roscoe Mitchell, for solo percussion, alto saxophone & piano, string quartet, alto saxophone quartet, baritone & chamber orchestra. Recorded live at Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Concert Hall, Mills College, Oakland, CA, March 31, 2012. Live recording and mixing by Robert Shumaker assisted by James Frazier.

Since the early 1960's composer Roscoe Mitchell has been a vital force in American music. An acclaimed saxophonist, Mitchell tours regularly throughout the United States and overseas. He is a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians and a founder of the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Recently he appeared to great critical acclaim with the Art Ensemble of Chicago and The Orchestra of the S.E.M Ensemble as soloist and composer on tours in the United States and Europe.

Recent compositions include Variations and Sketches From The Bamboo Terrace for chamber orchestra (1988), Contacts, Turbulents (1986), Memoirs of A Dying Parachutist for chamber orchestra with poetry by Daniel Moore (1995), Fallen Heroes for baritone and orchestra (1998), The Bells of Fifty Ninth Street for alto saxophone and Gamelan Orchestra (2000), 59A for solo soprano saxophone (2000), and Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City (2002) with text by Joseph Jarman.

TRACK LIST

Bells for New Orleans for tubular bells and orchestra bells (8:18)

Not Yet for alto saxophone and piano (13:16)

9/9/99 with Cards for string quartet (10:23)

Nonaah for alto saxophone quartet (11:37)

Would You Wear My Eyes? for baritone and chamber orchestra (9:44)

Nonaah for chamber orchestra (11:36)

REVIEWS

This is Roscoe Mitchell’s finest classical album yet. And, interestingly, it’s one on which his own horn playing is absent; he’s intent on fully inhabiting the role of composer. It’s no secret how a modern conceptualist gets good performances of fiercely difficult, experimental works: you get a chair in composition at a major music school, draw interested students to your side, and present concerts. Mitchell has done that as a chair of composition studies at Mills College. And his student Jacob Zimmerman does the teacher proud in the skittering, sheets-of-sound atonality of the title track (for saxophone and piano), as well as in the sax-quartet arrangement of the infamous Mitchell piece “Nonaah.” Some more senior eminences drop by to tackle a chamber orchestra version of “Nonaah,” also. When paired with the finest recorded example we have of Mitchell’s writing for string quartet (“9/9/99 with Cards”), this album becomes an essential document of a portion of the composer’s legacy. -Seth Colter Walls, eMusic

ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO IN LIVE PERFORMANCE, 1978:William Winant (percussion): Jacob Zimmerman (alto saxophone); Dan VanHassel (piano); Eclipse Quartet; James Fei Alto Quartet; Thomas Buckner (baritone); Petr Kotik (conductor)

A monumental recording of recent concert works by Roscoe Mitchell, for solo percussion, alto saxophone & piano, string quartet, alto saxophone quartet, baritone & chamber orchestra. Recorded live at Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Concert Hall, Mills College, Oakland, CA, March 31, 2012. Live recording and mixing by Robert Shumaker assisted by James Frazier.

Since the early 1960's composer Roscoe Mitchell has been a vital force in American music. An acclaimed saxophonist, Mitchell tours regularly throughout the United States and overseas. He is a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians and a founder of the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Recently he appeared to great critical acclaim with the Art Ensemble of Chicago and The Orchestra of the S.E.M Ensemble as soloist and composer on tours in the United States and Europe.

Recent compositions include Variations and Sketches From The Bamboo Terrace for chamber orchestra (1988), Contacts, Turbulents (1986), Memoirs of A Dying Parachutist for chamber orchestra with poetry by Daniel Moore (1995), Fallen Heroes for baritone and orchestra (1998), The Bells of Fifty Ninth Street for alto saxophone and Gamelan Orchestra (2000), 59A for solo soprano saxophone (2000), and Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City (2002) with text by Joseph Jarman.

TRACK LIST

Bells for New Orleans for tubular bells and orchestra bells (8:18)

Not Yet for alto saxophone and piano (13:16)

9/9/99 with Cards for string quartet (10:23)

Nonaah for alto saxophone quartet (11:37)

Would You Wear My Eyes? for baritone and chamber orchestra (9:44)

Nonaah for chamber orchestra (11:36)

REVIEWS

This is Roscoe Mitchell’s finest classical album yet. And, interestingly, it’s one on which his own horn playing is absent; he’s intent on fully inhabiting the role of composer. It’s no secret how a modern conceptualist gets good performances of fiercely difficult, experimental works: you get a chair in composition at a major music school, draw interested students to your side, and present concerts. Mitchell has done that as a chair of composition studies at Mills College. And his student Jacob Zimmerman does the teacher proud in the skittering, sheets-of-sound atonality of the title track (for saxophone and piano), as well as in the sax-quartet arrangement of the infamous Mitchell piece “Nonaah.” Some more senior eminences drop by to tackle a chamber orchestra version of “Nonaah,” also. When paired with the finest recorded example we have of Mitchell’s writing for string quartet (“9/9/99 with Cards”), this album becomes an essential document of a portion of the composer’s legacy. -Seth Colter Walls, eMusic

Roscoe Mitchell, as. ts. ss. fl.

Joseph Jarman, ss. ts. fl.

Malachi Favors, b.

Don Moye, dr. perc.

Lester Bowie, tp.

Recorded Willisau (Switzerland) Jazz Festival in 1978

"Jo Jar" by Roscoe Mitchell

Roscoe Mitchell Sound Ensemble

From recording: "3X4 EYE"

Recorded December 28, 1981

Black Saint Records (Italy)

Roscoe Mitchell: Composer, alto and tenor saxophones

Hugh Ragin: Trumpet & Piccolo trumpet

Jaribu Shahid: Bass

Tani Tabbal: Drums and percussion

Roscoe Mitchell Sound Ensemble

From recording: "3X4 EYE"

Recorded December 28, 1981

Black Saint Records (Italy)

Roscoe Mitchell: Composer, alto and tenor saxophones

Hugh Ragin: Trumpet & Piccolo trumpet

Jaribu Shahid: Bass

Tani Tabbal: Drums and percussion

MUSIC BY ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO:

Roscoe Mitchell: tenor, alto, baritone, and soprano saxophones, flute, percussion)

Joseph Jarman: tenor, alto, sopranino, and soprano saxophones, flute, percussion)

Lester Bowie: Trumpet, percussion)

Don Moye: Drums, percussion

Malachi Favors: Acoustic and electric bass, percussion)

"Theme De YoYo" (composition by AEC, 1970):

Roscoe Mitchell: tenor, alto, baritone, and soprano saxophones, flute, percussion)

Joseph Jarman: tenor, alto, sopranino, and soprano saxophones, flute, percussion)

Lester Bowie: Trumpet, percussion)

Don Moye: Drums, percussion

Malachi Favors: Acoustic and electric bass, percussion)

"Theme De YoYo" (composition by AEC, 1970):

Composed for the film: LES STANCES A SOPHIE

Recorded July 22, 1970 in Boulogne, France

'Theme De Yoyo"

(Music & Lyrics by the Art Ensemble of Chicago--the singer is FONTELLA BASS)

Your head is like a yoyo

your neck is like a string

Your body's like camembert

oozing from its skin.

Your fanny's like two sperm whales

floating down the Seine

Your voice is like a long fork

that's music to your brain.

Your eyes are two blind eagles

that kill what they can't see

Your hands are like two shovels

digging in me.

And your love is like an oil-well

Dig, dig, dig, dig it,

On the Champs-Elysees.

Recorded July 22, 1970 in Boulogne, France

'Theme De Yoyo"

(Music & Lyrics by the Art Ensemble of Chicago--the singer is FONTELLA BASS)

Your head is like a yoyo

your neck is like a string

Your body's like camembert

oozing from its skin.

Your fanny's like two sperm whales

floating down the Seine

Your voice is like a long fork

that's music to your brain.

Your eyes are two blind eagles

that kill what they can't see

Your hands are like two shovels

digging in me.

And your love is like an oil-well

Dig, dig, dig, dig it,

On the Champs-Elysees.

ROSCOE MITCHELL

Adventurous composer, jazz improviser, and iconoclastic saxophone don: Art Ensemble of Chicago’s Roscoe Mitchell looks back at his career.

When again did we start expecting art to be fluffy, calm and easy to digest, building a comfort zone for our weary heads to rest in? Well, that must’ve been a world before Roscoe Mitchell. Mitchell is one of the top saxophonists to emerge from the creative melting pot of 1960s Chicago. A key member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and the Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Mitchell gained notoriety as a particularly strong and adventurous improviser, pushing the boundaries of what was imaginable in the fields of jazz and Neue Musik. Take his seminal Sound (1966), an experimental behemoth of an album that incorporated toys, horns and random objects into the traditional sound palette. A prolific composer and performer, Mitchell’s charisma translates on record and stage, whether as part of a large ensemble, alongside the likes of Sun Ra and Pauline Oliveros, or in unaccompanied solo performances. Much celebrated is Mitchell’s rare ability to move, with apparent ease, from free and formal jazz into the realms of contemporary classical music and beyond. Some critics have chosen to award him the akward nimbus of the super musician – a hypothetical construct reserved for the type of genius that reigns over various styles, as s/he has deciphered the very DNA of a musical genre. But maybe they just didn’t get the humour.

Origin

Chicago, United States

Credits

NessaDIW

Links

The Art Ensemble Of Chicago

1 Thème De Yoyo

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Pathé Marconi

2 One Little Suite

Roscoe Mitchell Sextet

Delmark

3 A Jackson In Your House

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

BYG

4 Thème De Yoyo

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Pathé Marconi

5 Toro

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Freedom

6 Tutankhamun

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Freedom

7 Nice Guys

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

ECM

8 Ancient To The Future

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

DIW

9 Zombie

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

DIW

10 Strawberry Mango

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Atlantic

11 Hail We Now Sing Joy

Art Ensemble Of Chicago

Pi Recordings

ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO

"Odwalla" (composition by Roscoe Mitchell, 1972)

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2008/02/roscoe-mitchell-master-musiciancomposer.html

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on February 25, 2008):

Monday, February 25, 2008

Roscoe Mitchell--Master Musician/Composer in Residence

Roscoe Mitchell, Musician/Composer

All,

My wife and I attended Mr. Mitchell's talk and musical performance at 'The Marsh' in San Francisco last wednesday evening (February 20). Extraordinary lecture, exquisite music, and very informative question-and-answer session with a rapt and deeply appreciative audience. It was everything I had hoped for and expected and more. Roscoe is one of the most creative, important, and influential American musician/composers in the world over the past 40 years and as always it was a great pleasure to experience him and his music live. I have just about every single album and CD the man has led and appeared on since 1966 I'm very proud to say and it's absolutely thrilling that he will be here in the Bay Area for the next three years as the prestigious Darius Milhaud Chair of Composition at Oakland's Mills College. We are indeed very fortunate to have such a great artist in our midst.

Kofi

NOTE: For still more information about Mitchell and his music see article by New York Times critic Adam Shatz from 1999 directly following the new SF Chronicle article below. I will also soon be providing a discography of Mitchell's work on this site.

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=%2Fc%2Fa%2F2008%2F02%2F18%2FDDC7V3H8S.DTL

Roscoe Mitchell brings jazz history to Mills

David Rubien, Chronicle Staff Writer

Monday, February 18, 2008

The building that houses the music department at Mills College is undergoing rehabilitation, so Roscoe Mitchell, the saxophonist who was hired last fall as the Darius Milhaud Chair of Composition, has been given a temporary office in another hall down the road that winds through the leafy Oakland campus.

<<<>>>

The room is large but barely furnished, with a scratched-up '60s-vintage desk, an empty bookshelf and two grand pianos abutting each other. The wooden chair Mitchell is sitting in seems incommensurate with his status as perhaps the most prestigious instructor at one of the most prestigious graduate music schools in the country. Not that this seems to bother him.

"Yes, it is prestigious," he acknowledges nonchalantly. "A lot of great people have been in this chair" - not meaning the one he's sitting on. Previous occupants of the position, named after the French composer who taught at Mills from 1941 to 1971, include Lou Harrison, Iannis Xenakis, Pauline Oliveros and Anthony Braxton.

Talking to Mitchell, you get the sense that sitting in an old wooden chair and being an exalted professor are about equivalent in the grand scheme of things - at least at this particular moment, when he is concentrating on an interviewer with that uncanny focus jazz musicians have when they're listening to each other on the bandstand.

In fact, a cheap chair and a fancy professorship represent the twin poles of what Mitchell, 67, could have become, as a budding jazz artist blazing trails in sonic realms neither understood nor respected by many people - unless they happened to observe the music being performed, in which case they'd likely be tweaked for life.

Mitchell, who teaches composition and improvisation at Mills, is best known as one of the founding members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, a quintet that existed with its original personnel for 30 years, and continues with some fresh blood now that two of its members, trumpeter Lester Bowie and bassist Malachi Favors, have passed away. One of the great groups in all of jazz history, the Art Ensemble had the misfortune of doing its key work from the late '60s through the early '80s, something of a lost era in jazz. You didn't hear much about this incredibly fruitful period in the otherwise excellent documentary "Jazz," a shameful omission on director Ken Burns' part.

"I was lucky to be around people who were so committed to what they were doing, and that's what kept us going for so long," Mitchell says.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago grew out of two bands Mitchell formed in the early '60s, the Roscoe Mitchell Sextet and the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble. As did many important bands in jazz history - Charlie Parker's and John Coltrane's pioneering groups, for instance - the Art Ensemble embodied exactly the point that jazz had evolved to at the time of the band's existence. The Art Ensemble made and still makes astonishing, joyful, swinging, sometimes difficult music based not only on the revolutions of the '60s, but on bebop, big band swing, kitschy vaudeville, 20th century classical and African percussion.

When Mitchell's sextet released "Sound" on Delmark Records in 1966, it was the birth of a new approach to improvised music, one based on an examination of music almost at the level of wavelength, where the saxophonist set about dissecting individual notes in order to unlock their mysteries. In performance, Mitchell often showed off this approach in hypnotic solo saxophone playing with a remarkable circular breathing technique.

In the few dozen albums he's made as a leader outside the Art Ensemble, he's pursued this from-the-ground-up approach, erecting suites and sheets of sound with various combinations of musicians.

Larry Ochs, a founding member of the Rova Saxophone Quartet who organized the Improv: 21 "informance" series where Mitchell is talking Wednesday, says Mitchell has influenced countless musicians even if they don't realize it.

"When I was a young man, Roscoe's electrifying tenor solos on the Art Ensemble's live recording from a concert in Ann Arbor ("Bap-Tizum") was crucial to my own playing, and the band's recording 'Les Stances a Sophie,' which is probably still in my top 10 albums of all time, showed one critical way to combine forms and feelings that spoke to me," Ochs says. "And certainly the Art Ensemble pointed the way for Rova to see the value of keeping a band together for a long time."

The commitment factor emerged early on in Chicago when Mitchell, along with several other musicians who were rehearsing with pianist Muhal Richard Abrams' big band, decided to form an organization that would teach artists to become self-sufficient. That's when, in 1961, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music was born.

"We were able to establish a unit of people who gave us a foundation, where we really didn't have to be dependent on things that were outside of us," Mitchell says.

The association still exists today, and has spawned such artists as former Darius Milhaud Chair Braxton, reed player Henry Threadgill, trombonist George Lewis, keyboardist Amina Claudine Myers, violinist Leroy Jenkins, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith and dozens more.

Mitchell says that when he was a kid, all kinds of music were everywhere in Chicago. "If you went to a movie, after the movie there'd be Count Basie's big band. Duke Ellington. Ella Fitzgerald. Lester Young. On and on like that."

Mitchell took up the clarinet while attending Inglewood High School on Chicago's South Side. "Back then, it was kind of a normal rule that if you wanted to play saxophone, you had to start with clarinet."

In the Army, he says, he started "functioning 24 hours a day as a musician." While stationed in Orleans, France, Mitchell first saw a performance by another Army player, tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler. "He had an enormous sound on his instrument. And though I didn't quite understand what it was that he was doing ... he made a big impression on me - but not enough to deter me from studying a more straight-ahead form.

"It wasn't until I got out of the Army and I heard Coltrane's record 'Coltrane,' when he was doing 'Inch Worm' and 'Out of This World,' that I thought, 'Oh my god, you can do that?' And then I thought, 'OK, I better go back and listen to Eric Dolphy a bit.' And then I said, 'Hmm, I better pull out these Ornette Coleman records.' And then it all started to make sense to me."

Mitchell is much too earnest and self-possessed to indulge in hero worship, but when recalling his early infatuation with the mighty 'Trane, his eyes fog up a bit.

"Man, I used to go around and think: Oh my god, what must it be like to be going down the street, and someone asks you, 'What's your name?' and the reply would be, 'John Coltrane.' I couldn't imagine what that would be like."

Mitchell got to sit in with Coltrane, too. Drummer Jack DeJohnette - who was a friend of Mitchell's when they both played in that nascent Abrams big band - had a brief gig with Coltrane after Elvin Jones left the group. The band came through Chicago, and "Jack told Coltrane you should ask this guy to play. And I was like, 'Wait a minute, Jack, man.' But Coltrane did ask me to come up and play. ... It was a remarkable experience for me. I mean (drummer) Roy Haynes came in that night and sat in, and it ended up with the club owner putting us out of the club because we played so late."

As a scientist of sound, Mitchell seems uniquely suited to teaching. One approach he uses involves a scored-improvisational system he developed decades ago that he calls the "card catalog." It's a series of cards that contain different kinds of cues to help students with improvisation.

"I noticed that when it came time to improvise, my students would often make mistakes. So I derived this system to help them discover some different options."

The big picture for Mitchell as a teacher, though, is to help his students figure out their own paths.

"I think the best thing you can teach a person is how to learn," he says. "And once they discover their own individual approach to that - which is inside all of us - then all of a sudden they've opened up a door of endless resources."

Roscoe Mitchell: "Informance" conversation with Derk Richardson. 7:30 p.m. Wednesday. The Marsh, 1062 Valencia St., San Francisco. Tickets: $10. Call (415) 826-5750 or go to themarsh.org/rising.html.

Roscoe Mitchell with the Stanford Jazz Orchestra: 8 p.m. Feb. 27. Dinkelspiel Auditorium, Stanford University. Tickets: $10 general public; $5 students; free for Stanford students. Call (650) 723-2720 or go to music.stanford.edu.

To hear music by Roscoe Mitchell, go to sfgate.com/eguide.To see a video of Mitchell performing, go to youtube.com/watch?v=Tbfd8_U4Ac.

E-mail David Rubien at drubien@sfchronicle.com.

http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=%2Fc%2Fa%2F2008%2F02%2F18%2FDDC7V3H8S.DTL

This article appeared on page E - 1 of the San Francisco Chronicle

MUSIC: A Maestro Of Esoteric Invention Becomes Accessible

By ADAM SHATZ

Published: March 28, 1999

IN 1937 John Cage inaugurated a musical revolution in three sentences of typically Zenlike simplicity: ''Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.'' In the future, he declared, music would be replaced by a broader field of creativity, which he called ''the organization of sound.''

In 1966 Roscoe Mitchell, then a 26-year-old saxophonist living on the South Side of Chicago, released a stunning album called ''Sound.'' Mr. Mitchell's band looked like a jazz sextet, but it didn't play like one. For starters, the music had no fixed pulse: the drums were used atmospherically, not rhythmically. The solos were explorations of timbre and noise punctuated by long silences; the overall effect was a trippy suspension of time. ''Sound'' belonged as much to the future Cage envisioned as to the jazz tradition.

Any similarities to Cage, however, were serendipitous. Unlike Cage, a privileged insider who delighted in mischief, Mr. Mitchell was a purposeful outsider, intent on claiming new rights for himself and his peers. ''Sound'' was no mere esthetic experiment. It was a pointed challenge to what Mr. Mitchell's fellow Chicagoan Anthony Braxton has called ''the myth of the sweating brow'' -- the notion that black music is an expression of native grace rather than introspection. And in 1966, the year Stokely Carmichael raised the cry of black power, ''Sound'' had the force of a manifesto.

Roscoe Mitchell, whose album ''Nine to Get Ready'' has just appeared, is a leading member of jazz's forgotten avant-garde. Once hailed as an heir to Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, Mr. Mitchell found himself pushed to the margins in the 1980's by Wynton Marsalis and his traditionalist followers, who viewed free jazz as an evil second only to fusion. Since the early 90's, Mr. Mitchell has been staging a comeback, recording and performing at a furious clip. He might not be welcome at Lincoln Center, where musicians are expected to adhere to blues-derived forms and steer clear of European dissonances. But among younger jazz players who chafe at such restrictions, Mr. Mitchell is increasingly recognized as an elder statesman.

''Jazz,'' he said recently, ''is a part of the whole picture, but the communication lines are all over the place now. If you're truly in love with music, you can't help being affected by that fact.''

A small, wiry man with close-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair, Mr. Mitchell, 59, is best known as a member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, one of the most important free-jazz groups since Mr. Coleman's 1960's quartet. But it is in Mr. Mitchell's work as a solo performer and as a leader that he has expressed his vision most rigorously.

A saxophonist and flutist with a hard, acerbic sound reminiscent of Eric Dolphy, Mr. Mitchell has a predilection for unusual effects like circular breathing, a technique of simultaneously inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth that allows a musician to blow for marathon stretches. His compositions have been performed by a wide array of ensembles, ranging from his own experimental jazz bands to contemporary classical groups like the S.E.M. Ensemble.

Although he has been accused of making self-consciously cerebral music, he said: ''It does not bother me to hear my music described that way. I am a scientist involved in the study of music, and it may well be that my work possesses some of those qualities.''

On ''Nine to Get Ready,'' the scientist has unbuttoned his lab coat and delivered some of the most lyrically accessible music of his career. Half the album is devoted to Mr. Mitchell's thorny, stylishly polytonal chamber music. But the jazzier half blazes with feelings that Mr. Mitchell once seemed bent on renouncing in his pursuit of sonic invention.

The unusual nine-piece band on ''Nine to Get Ready'' is composed of Mr. Mitchell on reeds, his longtime associate George Lewis on trombone and Hugh Ragin on trumpet, simultaneously backed by two full rhythm sections: the pianists Craig Taborn and Matthew Shipp, the bassists Jaribu Shahid and William Parker and the drummers Tani Tabbal and Gerald Cleaver. As Mr. Mitchell pointed out, the rhythm sections ''can function together or separately.''

Although most of the music on ''Nine to Get Ready'' is notated, Mr. Mitchell's composing methods blur the line between written and improvised music. To preserve the spontaneity of improvised music, he uses written instructions and graphic symbols as well as notes in his sheet music. (In one concert, Mr. Mitchell divided a stage into squares, each containing suggestions for the performers, who would move from one to the next.) At the same time, Mr. Mitchell abhors off-the-cuff expressiveness; he expects musicians to shape each improvisation as if it were composed. As he put it, ''You've got to know your part in improvised music, too.''

MR. MITCHELL, who was born and reared in Chicago, reached musical maturity at a time when the South Side nearly surpassed New York as a center of jazz innovation. In the early 60's, Mr. Mitchell began playing in the pianist and composer Muhal Richard Abrams's Experimental Band, which gave birth to the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (now better known as simply A.A.C.M.). Drawing inspiration from the music of Mr. Coleman and from the politics of Malcolm X, the collective staged concerts and provided music lessons to inner-city children. ''We knew what happened to people who were out there on their own, and we didn't want to end up like that,'' Mr. Mitchell recalled. ''We wanted to have a scene that we controlled.''

The collective nurtured some of the most significant composers of the 70's and 80's, including Mr. Mitchell, Mr. Braxton and Henry Threadgill. ''There was a feeling of not waiting around for someone to say you're O.K.'' said Mr. Mitchell. ''You'd go to someone's concert, get really inspired and go back home to prepare for your own concert.'' A distinctive regional sound arose, one that valued shadings of color and structural experiments over rhythmic motion and soloing. If New York loft musicians were the action painters of free jazz, these Chicagoans were its constructivists, working through appropriation and collage.

In 1968, Mr. Mitchell founded the collective's flagship band, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, with the bassist Malachi Favors, the trumpeter Lester Bowie and the saxophonist Joseph Jarman. While traveling in France the next year, the Art Ensemble added the drummer Don Moye. Its motto was ''Great Black Music: Past, Present and Future.'' (Early album titles like ''Certain Blacks Do What They Wanna! -- Join Them!'' gave the band a certain radical chic cachet.) The Art Ensemble produced sophisticated pastiches of advanced jazz, big band music, blues, African percussion and reggae that honored -- and sent up -- the black musical tradition.

Mr. Mitchell was the band's intellectual-in-residence. (Mr. Bowie was its jester, Mr. Jarman its mystic.) He was also the only member to appear on stage in street clothes. Since Mr. Moye, Mr. Favors and Mr. Jarman covered their faces with tribal paint and Mr. Bowie wore a physician's suit, Mr. Mitchell's appearance was a symbolic rejection of ornament. It reflected the lean, analytic style he was cultivating as a composer.

Although Mr. Mitchell still performs with the Art Ensemble, since the late 70's he has focused on his work as a composer and leader. In 1976, he moved with his family to a big farm in Wisconsin, where he could finally hear, he said, ''silence and the way things move in nature.'' As he explained: ''When you're in the city you're always being influenced by what's going on around you. I needed to get out of the city to find myself, though I admit when I first looked in the mirror I didn't see all that much. I found that I wasn't all that great and I kept working, from morning to night.''

On his records, Mr. Mitchell has painstakingly documented this process of self-examination. Although he has produced marvels like the 1981 album ''Snurdy McGurdy and Her Dancin' Shoes,'' some of his records demonstrated that avant-garde jazz could be as arid as academic serialism. With ''Nine to Get Ready'' -- his best record since ''Snurdy'' -- Mr. Mitchell has succeeded in fusing his scientific investigations of sound with the humanism of his Art Ensemble work. The chamber pieces have an unusual suppleness; the ballads are almost voluptuous. The opening track, ''Leola,'' is a breathtaking requiem for the composer's stepmother. In ''Jamaican Farewell,'' a beautiful, cloud-like formation, Mr. Ragin's trumpeting sounds virtually Coplandesque.

Mr. Mitchell, who now lives in Madison, Wis., leads a fairly ascetic life for a jazz musician. He often wakes up early to run through Bach's flute sonatas with Joan Wildman, a pianist on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin, where he occasionally teaches. He spends most of the day composing, studying and practicing. Baroque music is his latest obsession, and he has been transcribing some of his compositions for a recorder orchestra. ''Berkeley Fudge, a saxophonist, gave me my recorder, and it felt so natural, just the one key and the six holes,'' he said. ''And of course the sound is just incredible. I've been in a lot of halls in Italy that were just built for that sound.''

If all of this seems a long way from his Chicago jazz roots, Mr. Mitchell continues to uphold what he calls ''A.A.C.M. philosophy.'' His dream, he said, is to set up a collective of his own -- in the country, of course: ''I'd love to have a school and a big performance space. And I'd love to have a state of the art video studio because the only example we have is MTV.'' He paused, then added: ''I'd never have to leave the house. Can you think of a hipper life than that?''

Adam Shatz's most recent article for Arts and Leisure was on DJ interpretations of Steve Reich's music.

Posted by Kofi Natambu at 6:13 AM

Roscoe Mitchell, Musician/Composer

All,

My wife and I attended Mr. Mitchell's talk and musical performance at 'The Marsh' in San Francisco last wednesday evening (February 20). Extraordinary lecture, exquisite music, and very informative question-and-answer session with a rapt and deeply appreciative audience. It was everything I had hoped for and expected and more. Roscoe is one of the most creative, important, and influential American musician/composers in the world over the past 40 years and as always it was a great pleasure to experience him and his music live. I have just about every single album and CD the man has led and appeared on since 1966 I'm very proud to say and it's absolutely thrilling that he will be here in the Bay Area for the next three years as the prestigious Darius Milhaud Chair of Composition at Oakland's Mills College. We are indeed very fortunate to have such a great artist in our midst.

Kofi

NOTE: For still more information about Mitchell and his music see article by New York Times critic Adam Shatz from 1999 directly following the new SF Chronicle article below. I will also soon be providing a discography of Mitchell's work on this site.

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=%2Fc%2Fa%2F2008%2F02%2F18%2FDDC7V3H8S.DTL

Roscoe Mitchell brings jazz history to Mills

David Rubien, Chronicle Staff Writer

Monday, February 18, 2008

The building that houses the music department at Mills College is undergoing rehabilitation, so Roscoe Mitchell, the saxophonist who was hired last fall as the Darius Milhaud Chair of Composition, has been given a temporary office in another hall down the road that winds through the leafy Oakland campus.

<<<>>>

The room is large but barely furnished, with a scratched-up '60s-vintage desk, an empty bookshelf and two grand pianos abutting each other. The wooden chair Mitchell is sitting in seems incommensurate with his status as perhaps the most prestigious instructor at one of the most prestigious graduate music schools in the country. Not that this seems to bother him.

"Yes, it is prestigious," he acknowledges nonchalantly. "A lot of great people have been in this chair" - not meaning the one he's sitting on. Previous occupants of the position, named after the French composer who taught at Mills from 1941 to 1971, include Lou Harrison, Iannis Xenakis, Pauline Oliveros and Anthony Braxton.

Talking to Mitchell, you get the sense that sitting in an old wooden chair and being an exalted professor are about equivalent in the grand scheme of things - at least at this particular moment, when he is concentrating on an interviewer with that uncanny focus jazz musicians have when they're listening to each other on the bandstand.

In fact, a cheap chair and a fancy professorship represent the twin poles of what Mitchell, 67, could have become, as a budding jazz artist blazing trails in sonic realms neither understood nor respected by many people - unless they happened to observe the music being performed, in which case they'd likely be tweaked for life.

Mitchell, who teaches composition and improvisation at Mills, is best known as one of the founding members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, a quintet that existed with its original personnel for 30 years, and continues with some fresh blood now that two of its members, trumpeter Lester Bowie and bassist Malachi Favors, have passed away. One of the great groups in all of jazz history, the Art Ensemble had the misfortune of doing its key work from the late '60s through the early '80s, something of a lost era in jazz. You didn't hear much about this incredibly fruitful period in the otherwise excellent documentary "Jazz," a shameful omission on director Ken Burns' part.

"I was lucky to be around people who were so committed to what they were doing, and that's what kept us going for so long," Mitchell says.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago grew out of two bands Mitchell formed in the early '60s, the Roscoe Mitchell Sextet and the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble. As did many important bands in jazz history - Charlie Parker's and John Coltrane's pioneering groups, for instance - the Art Ensemble embodied exactly the point that jazz had evolved to at the time of the band's existence. The Art Ensemble made and still makes astonishing, joyful, swinging, sometimes difficult music based not only on the revolutions of the '60s, but on bebop, big band swing, kitschy vaudeville, 20th century classical and African percussion.

When Mitchell's sextet released "Sound" on Delmark Records in 1966, it was the birth of a new approach to improvised music, one based on an examination of music almost at the level of wavelength, where the saxophonist set about dissecting individual notes in order to unlock their mysteries. In performance, Mitchell often showed off this approach in hypnotic solo saxophone playing with a remarkable circular breathing technique.

In the few dozen albums he's made as a leader outside the Art Ensemble, he's pursued this from-the-ground-up approach, erecting suites and sheets of sound with various combinations of musicians.

Larry Ochs, a founding member of the Rova Saxophone Quartet who organized the Improv: 21 "informance" series where Mitchell is talking Wednesday, says Mitchell has influenced countless musicians even if they don't realize it.

"When I was a young man, Roscoe's electrifying tenor solos on the Art Ensemble's live recording from a concert in Ann Arbor ("Bap-Tizum") was crucial to my own playing, and the band's recording 'Les Stances a Sophie,' which is probably still in my top 10 albums of all time, showed one critical way to combine forms and feelings that spoke to me," Ochs says. "And certainly the Art Ensemble pointed the way for Rova to see the value of keeping a band together for a long time."

The commitment factor emerged early on in Chicago when Mitchell, along with several other musicians who were rehearsing with pianist Muhal Richard Abrams' big band, decided to form an organization that would teach artists to become self-sufficient. That's when, in 1961, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music was born.

"We were able to establish a unit of people who gave us a foundation, where we really didn't have to be dependent on things that were outside of us," Mitchell says.

The association still exists today, and has spawned such artists as former Darius Milhaud Chair Braxton, reed player Henry Threadgill, trombonist George Lewis, keyboardist Amina Claudine Myers, violinist Leroy Jenkins, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith and dozens more.

Mitchell says that when he was a kid, all kinds of music were everywhere in Chicago. "If you went to a movie, after the movie there'd be Count Basie's big band. Duke Ellington. Ella Fitzgerald. Lester Young. On and on like that."

Mitchell took up the clarinet while attending Inglewood High School on Chicago's South Side. "Back then, it was kind of a normal rule that if you wanted to play saxophone, you had to start with clarinet."

In the Army, he says, he started "functioning 24 hours a day as a musician." While stationed in Orleans, France, Mitchell first saw a performance by another Army player, tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler. "He had an enormous sound on his instrument. And though I didn't quite understand what it was that he was doing ... he made a big impression on me - but not enough to deter me from studying a more straight-ahead form.

"It wasn't until I got out of the Army and I heard Coltrane's record 'Coltrane,' when he was doing 'Inch Worm' and 'Out of This World,' that I thought, 'Oh my god, you can do that?' And then I thought, 'OK, I better go back and listen to Eric Dolphy a bit.' And then I said, 'Hmm, I better pull out these Ornette Coleman records.' And then it all started to make sense to me."

Mitchell is much too earnest and self-possessed to indulge in hero worship, but when recalling his early infatuation with the mighty 'Trane, his eyes fog up a bit.

"Man, I used to go around and think: Oh my god, what must it be like to be going down the street, and someone asks you, 'What's your name?' and the reply would be, 'John Coltrane.' I couldn't imagine what that would be like."

Mitchell got to sit in with Coltrane, too. Drummer Jack DeJohnette - who was a friend of Mitchell's when they both played in that nascent Abrams big band - had a brief gig with Coltrane after Elvin Jones left the group. The band came through Chicago, and "Jack told Coltrane you should ask this guy to play. And I was like, 'Wait a minute, Jack, man.' But Coltrane did ask me to come up and play. ... It was a remarkable experience for me. I mean (drummer) Roy Haynes came in that night and sat in, and it ended up with the club owner putting us out of the club because we played so late."

As a scientist of sound, Mitchell seems uniquely suited to teaching. One approach he uses involves a scored-improvisational system he developed decades ago that he calls the "card catalog." It's a series of cards that contain different kinds of cues to help students with improvisation.

"I noticed that when it came time to improvise, my students would often make mistakes. So I derived this system to help them discover some different options."

The big picture for Mitchell as a teacher, though, is to help his students figure out their own paths.

"I think the best thing you can teach a person is how to learn," he says. "And once they discover their own individual approach to that - which is inside all of us - then all of a sudden they've opened up a door of endless resources."

Roscoe Mitchell: "Informance" conversation with Derk Richardson. 7:30 p.m. Wednesday. The Marsh, 1062 Valencia St., San Francisco. Tickets: $10. Call (415) 826-5750 or go to themarsh.org/rising.html.

Roscoe Mitchell with the Stanford Jazz Orchestra: 8 p.m. Feb. 27. Dinkelspiel Auditorium, Stanford University. Tickets: $10 general public; $5 students; free for Stanford students. Call (650) 723-2720 or go to music.stanford.edu.

To hear music by Roscoe Mitchell, go to sfgate.com/eguide.To see a video of Mitchell performing, go to youtube.com/watch?v=Tbfd8_U4Ac.

E-mail David Rubien at drubien@sfchronicle.com.

http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=%2Fc%2Fa%2F2008%2F02%2F18%2FDDC7V3H8S.DTL

This article appeared on page E - 1 of the San Francisco Chronicle

MUSIC: A Maestro Of Esoteric Invention Becomes Accessible

By ADAM SHATZ

Published: March 28, 1999

IN 1937 John Cage inaugurated a musical revolution in three sentences of typically Zenlike simplicity: ''Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.'' In the future, he declared, music would be replaced by a broader field of creativity, which he called ''the organization of sound.''

In 1966 Roscoe Mitchell, then a 26-year-old saxophonist living on the South Side of Chicago, released a stunning album called ''Sound.'' Mr. Mitchell's band looked like a jazz sextet, but it didn't play like one. For starters, the music had no fixed pulse: the drums were used atmospherically, not rhythmically. The solos were explorations of timbre and noise punctuated by long silences; the overall effect was a trippy suspension of time. ''Sound'' belonged as much to the future Cage envisioned as to the jazz tradition.

Any similarities to Cage, however, were serendipitous. Unlike Cage, a privileged insider who delighted in mischief, Mr. Mitchell was a purposeful outsider, intent on claiming new rights for himself and his peers. ''Sound'' was no mere esthetic experiment. It was a pointed challenge to what Mr. Mitchell's fellow Chicagoan Anthony Braxton has called ''the myth of the sweating brow'' -- the notion that black music is an expression of native grace rather than introspection. And in 1966, the year Stokely Carmichael raised the cry of black power, ''Sound'' had the force of a manifesto.

Roscoe Mitchell, whose album ''Nine to Get Ready'' has just appeared, is a leading member of jazz's forgotten avant-garde. Once hailed as an heir to Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, Mr. Mitchell found himself pushed to the margins in the 1980's by Wynton Marsalis and his traditionalist followers, who viewed free jazz as an evil second only to fusion. Since the early 90's, Mr. Mitchell has been staging a comeback, recording and performing at a furious clip. He might not be welcome at Lincoln Center, where musicians are expected to adhere to blues-derived forms and steer clear of European dissonances. But among younger jazz players who chafe at such restrictions, Mr. Mitchell is increasingly recognized as an elder statesman.

''Jazz,'' he said recently, ''is a part of the whole picture, but the communication lines are all over the place now. If you're truly in love with music, you can't help being affected by that fact.''

A small, wiry man with close-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair, Mr. Mitchell, 59, is best known as a member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, one of the most important free-jazz groups since Mr. Coleman's 1960's quartet. But it is in Mr. Mitchell's work as a solo performer and as a leader that he has expressed his vision most rigorously.

A saxophonist and flutist with a hard, acerbic sound reminiscent of Eric Dolphy, Mr. Mitchell has a predilection for unusual effects like circular breathing, a technique of simultaneously inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth that allows a musician to blow for marathon stretches. His compositions have been performed by a wide array of ensembles, ranging from his own experimental jazz bands to contemporary classical groups like the S.E.M. Ensemble.

Although he has been accused of making self-consciously cerebral music, he said: ''It does not bother me to hear my music described that way. I am a scientist involved in the study of music, and it may well be that my work possesses some of those qualities.''

On ''Nine to Get Ready,'' the scientist has unbuttoned his lab coat and delivered some of the most lyrically accessible music of his career. Half the album is devoted to Mr. Mitchell's thorny, stylishly polytonal chamber music. But the jazzier half blazes with feelings that Mr. Mitchell once seemed bent on renouncing in his pursuit of sonic invention.

The unusual nine-piece band on ''Nine to Get Ready'' is composed of Mr. Mitchell on reeds, his longtime associate George Lewis on trombone and Hugh Ragin on trumpet, simultaneously backed by two full rhythm sections: the pianists Craig Taborn and Matthew Shipp, the bassists Jaribu Shahid and William Parker and the drummers Tani Tabbal and Gerald Cleaver. As Mr. Mitchell pointed out, the rhythm sections ''can function together or separately.''

Although most of the music on ''Nine to Get Ready'' is notated, Mr. Mitchell's composing methods blur the line between written and improvised music. To preserve the spontaneity of improvised music, he uses written instructions and graphic symbols as well as notes in his sheet music. (In one concert, Mr. Mitchell divided a stage into squares, each containing suggestions for the performers, who would move from one to the next.) At the same time, Mr. Mitchell abhors off-the-cuff expressiveness; he expects musicians to shape each improvisation as if it were composed. As he put it, ''You've got to know your part in improvised music, too.''