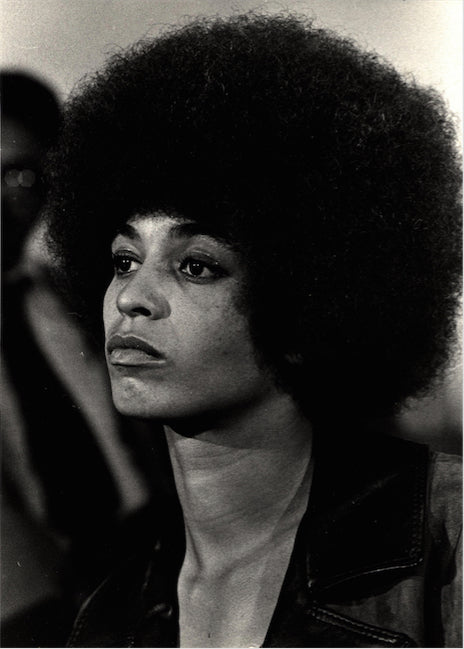

ANGELA DAVIS

(b. January 26, 1944)

(b. January 26, 1944)

"Free Angela and All Political Prisoners"

University of California Television (UCTV)

(Visit: http://www.uctv.tv/)

University of California Television (UCTV)

(Visit: http://www.uctv.tv/)

Angela Davis visited UC Santa Barbara for a screening of "Free Angela and All Political Prisoners," a 2013 documentary by Shola Lynch that chronicles Davis's life as a young, outspoken UCLA professor. Angela Davis and producer Sidra Smith answer questions from the audience. Recorded on 10/10/2013. Series: "Carsey-Wolf Center" [1/2014] [Humanities]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1wr-BXtIW0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EhObhSenc5s

:

:

Angela Davis and Michelle Alexander - End Mass Incarceration - Riverside Church in New York City - September 14, 2012

Angela Davis and Michelle Alexander take part in a panel discussion on the issue of mass incarceration at Riverside Church in New York City on September 14, 2012. They answer the questions of, what is the problem of mass incarceration and what does it say about the United States society?

ANGELA DAVIS & MICHELLE ALEXANDER

Opinion

‘Free Angela’ documentary revels in Angela Davis’ political rise and liberation

by Courtney Garcia

February 19, 2013

The Grio

Many words describe Angela Davis – radical, intellectual, Communist, feminist, rebel, scholar, revolutionary– but the story of her life can be defined by one: justice.

As a civil rights activist and prison abolitionist, Davis has spent decades fighting for a fair society, and in the process, circumventing the systematic prejudices she so fervently denounces. In the new documentary Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, filmmaker Shola Lynch explores the moment 41 years ago that Davis became an international political icon, a woman both exalted and vilified as she fought for the right to assert her beliefs, her speech and consequently her liberty.

“In the landscape of that period, when you think about political figures, when you think about mass media figures, there are very few examples, if any, of strong women,” Lynch tells theGrio. “Let alone strong black women.”

The movie centers on Davis’ implication in a courthouse murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy effort on August 7, 1970 in Marin County, California, the trial that ensued thereafter and Davis’ eventual acquittal. Though only 26 years old at the time, it was the culmination of a riotous period in Davis’ life, where she had already been labeled a terrorist by the government, and fired from her job as a professor at UCLA.

“Angela Davis is associated with [the Black Panthers] and she stands up for her rights and her beliefs,” Lynch explains. “It starts with UCLA and standing up for her job. It went against the school policy and the law, I’m pretty sure, for the school to try and fire her for being a Communist…That’s what democracy is all about, that we have freedom of speech, and academic freedom, within the context of the university, to discuss ideas that may or may not be popular. So, the idea that she was standing up for her rights unequivocally is very attractive.”

After receiving death threats for her socialist ties, Davis was linked to George Jackson, a Panther and member of the Soledad Brothers trio, when a gun she’d purchased for defense was used during his courthouse ambush. Several people were killed, and Davis was indicted for her connection to the crime. She went into hiding following the incident, becoming the third woman ever to appear on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List, and was eventually captured and detained without bail as she went on trial.

Lynch spent eight years researching Davis’ story and bringing the film project to fruition. It serves as a recounting of a significant moment in Davis’ life that would influence her future work, and inspire a faction of constituents backing her cause.

by Courtney Garcia

February 19, 2013

The Grio

Many words describe Angela Davis – radical, intellectual, Communist, feminist, rebel, scholar, revolutionary– but the story of her life can be defined by one: justice.

As a civil rights activist and prison abolitionist, Davis has spent decades fighting for a fair society, and in the process, circumventing the systematic prejudices she so fervently denounces. In the new documentary Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, filmmaker Shola Lynch explores the moment 41 years ago that Davis became an international political icon, a woman both exalted and vilified as she fought for the right to assert her beliefs, her speech and consequently her liberty.

“In the landscape of that period, when you think about political figures, when you think about mass media figures, there are very few examples, if any, of strong women,” Lynch tells theGrio. “Let alone strong black women.”

The movie centers on Davis’ implication in a courthouse murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy effort on August 7, 1970 in Marin County, California, the trial that ensued thereafter and Davis’ eventual acquittal. Though only 26 years old at the time, it was the culmination of a riotous period in Davis’ life, where she had already been labeled a terrorist by the government, and fired from her job as a professor at UCLA.

“Angela Davis is associated with [the Black Panthers] and she stands up for her rights and her beliefs,” Lynch explains. “It starts with UCLA and standing up for her job. It went against the school policy and the law, I’m pretty sure, for the school to try and fire her for being a Communist…That’s what democracy is all about, that we have freedom of speech, and academic freedom, within the context of the university, to discuss ideas that may or may not be popular. So, the idea that she was standing up for her rights unequivocally is very attractive.”

After receiving death threats for her socialist ties, Davis was linked to George Jackson, a Panther and member of the Soledad Brothers trio, when a gun she’d purchased for defense was used during his courthouse ambush. Several people were killed, and Davis was indicted for her connection to the crime. She went into hiding following the incident, becoming the third woman ever to appear on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List, and was eventually captured and detained without bail as she went on trial.

Lynch spent eight years researching Davis’ story and bringing the film project to fruition. It serves as a recounting of a significant moment in Davis’ life that would influence her future work, and inspire a faction of constituents backing her cause.

SHOLA LYNCH

(b. 1969)

(b. 1969)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YxGO6JCgLDQ

ANGELA DAVIS

Welcome To Detroit!

October 24, 2012

ANGELA DAVIS

Welcome To Detroit!

October 24, 2012

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9jXEIvNtZTs

ANGELA DAVIS SPEAKING:

"Racism is a much more clandestine, much more hidden kind of phenomenon, but at the same time it's perhaps far more terrible than it's ever been."

"As a black woman, my politics and political affiliation are bound up with and flow from participation in my people's struggle for liberation, and with the fight of oppressed people all over the world against American imperialism."

"I think the importance of doing activist work is precisely because it allows you to give back and to consider yourself not as a single individual who may have achieved whatever but to be a part of an ongoing historical movement."

"To understand how any society functions you must understand the relationship between the men and the women."

"Racism, in the first place, is a weapon used by the wealthy to increase the profits they bring in by paying Black workers less for their work."

"Jails and prisons are designed to break human beings, to convert the population into specimens in a zoo - obedient to our keepers, but dangerous to each other."

"Radical simply means 'grasping things at the root.'"

"I'm suggesting that we abolish the social function of prisons."

"Now, if we look at the way in which the labor movement itself has evolved over the last couple of decades, we see increasing numbers of black people who are in the leadership of the labor movement and this is true today."

"What this country needs is more unemployed politicians."

"I decided to teach because I think that any person who studies philosophy has to be involved actively."

"And I guess what I would say is that we can't think narrowly about movements for black liberation and we can't necessarily see this class division as simply a product or a certain strategy that black movements have developed for liberation."

"I'm involved in the work around prison rights in general."

"We know the road to freedom has always been stalked by death."

"Had it not been for slavery, the death penalty would have likely been abolished in America. Slavery became a haven for the death penalty."

"We have to talk about liberating minds as well as liberating society."

"Progressive art can assist people to learn not only about the objective forces at work in the society in which they live, but also about the intensely social character of their interior lives. Ultimately, it can propel people toward social emancipation."

"Because it would be too agonizing to cope with the possibility that anyone, including ourselves, could become a prisoner, we tend to think of the prison as disconnected from our own lives. This is even true for some of us, women as well as men, who have already experienced imprisonment."

""The prison is not the only institution that has posed complex challenges to the people who have lived with it and have become so inured to its presence that they could not conceive of society without it. Within the history of the United States the system of slavery immediately comes to mind."

ANGELA DAVIS IN 1969

MICHELLE ALEXANDER

(b. October 7, 1967)

(b. October 7, 1967)

Michelle Alexander is the author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010)

Michelle Alexander (author) in Portland on Jan 16th at 7pm

Doors Opened at 5PM - This video opens w/ a speaker panel before author speaks.

Michelle speaks in this video at 1:08:08

This event was at Emmanuel Temple Church (1033 N. Sumner St.) near the Cascade Campus

Michelle Alexander is an associate professor of law at Ohio State University, a civil rights advocate and a writer.

In this video, Michelle Alexander, discuss concepts from her new book, "The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness." with over 1200 people, who filled every seat in the church here in North Portland Oregon.

This video file is two and a half hours long, it opens with a community panel that discuss topics of Alexander's lecture from 5:45-6:45 p.m.

Michelle Alexander (author) in Portland on Jan 16th at 7pm

Doors Opened at 5PM - This video opens w/ a speaker panel before author speaks.

Michelle speaks in this video at 1:08:08

This event was at Emmanuel Temple Church (1033 N. Sumner St.) near the Cascade Campus

Michelle Alexander is an associate professor of law at Ohio State University, a civil rights advocate and a writer.

In this video, Michelle Alexander, discuss concepts from her new book, "The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness." with over 1200 people, who filled every seat in the church here in North Portland Oregon.

This video file is two and a half hours long, it opens with a community panel that discuss topics of Alexander's lecture from 5:45-6:45 p.m.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQ2cC7LHMxA

"Slavery and the Prison Industrial Complex"

5th Annual Eric Williams Memorial Lecture at Florida International University

Date: 9-19-2003:

Speaker: Angela Davis,

5th Annual Eric Williams Memorial Lecture at Florida International University

Date: 9-19-2003:

Speaker: Angela Davis,

Professor in History of Consciousness and Chair of Women's Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angela_Davis

Angela Davis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Angela Davis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Born Angela Yvonne Davis

January 26, 1944 (age 70)

Birmingham, Alabama, U.S.

Alma mater Brandeis University, B.A.

UC San Diego, M.A.

Humboldt University, Ph.D.

Occupation Educator, author, activist

Employer UC Santa Cruz (retired)

Political party

Communist Party USA (1969–1991), Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (1991–currently)

Spouse(s) Hilton Braithwaite[1]

Relatives Ben Davis (brother); Reginald Davis (brother); Fania Davis Jordan (sister)

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, scholar, Communist and author. She emerged as a nationally prominent counterculture activist and radical in the 1960s, as a leader of the Communist Party USA, and had close relations with the Black Panther Party through her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement despite never being an official member of the party. Prisoner rights have been among her continuing interests; she is the founder of Critical Resistance, an organization working to abolish the prison-industrial complex. She is a retired professor with the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and is the former director of the university's Feminist Studies department.[2]

Her research interests are in feminism, African-American studies, critical theory, Marxism, popular music, social consciousness, and the philosophy and history of punishment and prisons. Her membership in the Communist Party led to Ronald Reagan's request in 1969 to have her barred from teaching at any university in the State of California. She was tried and acquitted of suspected involvement in the Soledad brothers' August 1970 abduction and murder of Judge Harold Haley in Marin County, California. She was twice a candidate for Vice President on the Communist Party USA ticket during the 1980s.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Education

2.1 Brandeis University

2.2 University of Frankfurt

2.3 Postgraduate work

3 University of California, Los Angeles

4 Arrest and trial

5 In Cuba

6 Criticism by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

7 Activism

8 Teaching

9 Bibliography

9.1 Angela Davis interviews and appearances in audiovisual materials

9.2 Archives

10 See also

11 References

12 External links

Early life

Davis was born in Birmingham, Alabama. Her father, Frank Davis, was a graduate of St. Augustine's College, a historically black college in Raleigh, North Carolina, and was briefly a high school history teacher. Her father later owned and operated a service station in the black section of Birmingham. Her mother, Sallye Davis, a graduate of Miles College in Birmingham, was an elementary school teacher.

The family lived in the "Dynamite Hill" neighborhood, which was marked by racial conflict. Davis was occasionally able to spend time on her uncle's farm and with friends in New York City.[3] Her brother, Ben Davis, played defensive back for the Cleveland Browns and Detroit Lions in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Davis also has another brother, Reginald Davis, and sister, Fania Davis Jordan.[4]

Davis attended Carrie A. Tuggle School, a black elementary school; later she attended Parker Annex, a middle-school branch of Parker High School in Birmingham. During this time Davis' mother was a national officer and leading organizer of the Southern Negro Congress, an organization heavily influenced by the Communist Party. Consequently Davis grew up surrounded by communist organizers and thinkers who significantly influenced her intellectual development growing up.[5] By her junior year, she had applied to and was accepted at an American Friends Service Committee program that placed black students from the South in integrated schools in the North. She chose Elisabeth Irwin High School in Greenwich Village in New York City. There she was introduced to socialism and communism and was recruited by a Communist youth group, Advance. She also met children of some of the leaders of the Communist Party USA, including her lifelong friend, Bettina Aptheker.[6]

Education[edit]

Brandeis University

Davis was awarded a scholarship to Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, where she was one of three black students in her freshman class. She initially felt alienated by the isolation of the campus (at that time she was interested in Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre), but she soon made friends with foreign students. She encountered the Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse at a rally during the Cuban Missile Crisis and then became his student. In a television interview, she said "Herbert Marcuse taught me that it was possible to be an academic, an activist, a scholar, and a revolutionary."[7] She worked part-time to earn enough money to travel to France and Switzerland before she went on to attend the eighth World Festival of Youth and Students in Helsinki, Finland. She returned home in 1963 to a Federal Bureau of Investigation interview about her attendance at the Communist-sponsored festival.[8]

During her second year at Brandeis, she decided to major in French and continued her intensive study of Sartre. Davis was accepted by the Hamilton College Junior Year in France Program. Classes were initially at Biarritz and later at the Sorbonne. In Paris, she and other students lived with a French family. It was at Biarritz that she received news of the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, committed by the members of the Ku Klux Klan, an occasion that deeply affected her, because, she wrote, she was personally acquainted with the young victims.[8]

Nearing completion of her degree in French, Davis realized her major interest was in philosophy instead. She became particularly interested in the ideas of Herbert Marcuse and on her return to Brandeis she sat in on his course. Marcuse, she wrote, turned out to be approachable and helpful. Davis began making plans to attend the University of Frankfurt for graduate work in philosophy. In 1965 she graduated magna cum laude, a member of Phi Beta Kappa.[8]

University of Frankfurt

In Germany, with a stipend of $100 a month, she first lived with a German family. Later, she moved with a group of students into a loft in an old factory. After visiting East Berlin during the annual May Day celebration, she felt that the East German government was dealing better with the residual effects of fascism than were the West Germans. Many of her roommates were active in the radical Socialist German Student Union (SDS), and Davis participated in SDS actions, but events unfolding in the United States, including the formation of the Black Panther Party and the transformation of SNCC, encouraged her to return to the U.S.[8]

Postgraduate work

Marcuse, in the meantime, had moved to the University of California, San Diego, and Davis followed him there after her two years in Frankfurt.[8]

Returning to the United States, Davis stopped in London to attend a conference on "The Dialectics of Liberation." The black contingent at the conference included the American Stokely Carmichael and the British Michael X. Although moved by Carmichael's fiery rhetoric, she was disappointed by her colleagues' black nationalist sentiments and their rejection of communism as a "white man's thing." She held the view that any nationalism was a barrier to grappling with the underlying issue, capitalist domination of working people of all races.[9]

Davis earned her master's degree from the San Diego campus and her doctorate in philosophy from Humboldt University in East Berlin.[10]

University of California, Los Angeles[edit]

Davis was an acting assistant professor in the philosophy department at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), beginning in 1969. Although both Princeton and Swarthmore had expressed interest in having her join their respective philosophy departments, she opted for UCLA because of its urban location.[11] At that time, she also was known as a radical feminist and activist, a member of the Communist Party USA and an associate of the Black Panther Party.[2]

The Board of Regents of the University of California, urged by then-California Governor Ronald Reagan, fired her from her $10,000 a year post in 1969 because of her membership in the Communist Party. The Board of Regents was censured by the American Association of University Professors for their failure to reappoint Davis after her teaching contract expired.[12] On October 20, when Judge Jerry Pacht ruled the Regents could not fire Davis because of her affiliations with the Communist Party, she resumed her post.[13)

The Regents, unhappy with the decision, continued to search for ways to release Davis from her position at UCLA. They finally accomplished this on June 20, 1970, when they fired Davis for the “inflammatory language” she had used on four different speeches. “We deem particularly offensive,” the report said, “such utterances as her statement that the regents ‘killed, brutalized (and) murdered' the People's Park demonstrators, and her repeated characterizations of the police as ‘pigs.'”[14][15][16]

Arrest and trial

See also: Marin County courthouse incident

On August 7, 1970, Jonathan Jackson, a heavily armed, 17-year-old African-American high-school student, gained control over a courtroom in Marin County, California. Once in the courtroom, Jackson armed the black defendants and took Judge Harold Haley, the prosecutor, and three female jurors as hostages.[17][18] As Jackson transported the hostages and two black convicts away from the courtroom, the police began shooting at the vehicle. The judge and the three black men were killed in the melee; one of the jurors and the prosecutor were injured. Davis had purchased the firearms used in the attack, including the shotgun used to kill Haley, which had been bought two days prior and the barrel sawed off.[18] Since California considers “all persons concerned in the commission of a crime, whether they directly commit the act constituting the offense... principals in any crime so committed,” San Marin County Superior Judge Peter Allen Smith charged Davis with “aggravated kidnapping and first degree murder in the death of Judge Harold Haley” and issued a warrant for her arrest. Hours after the judge issued the warrant on August 14, 1970 a massive attempt to arrest Angela Davis began. On August 18, 1970, four days after the initial warrant was issued, the FBI director J. Edgar Hoover made Angela Davis the third woman and the 309th person to appear on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List.[17][19]

Soon after, Davis became a fugitive and fled California. According to her autobiography, during this time she hid in friends' homes and moved from place to place at night. On October 13, 1970, FBI agents found her at the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge in New York City.[20] President Richard M. Nixon congratulated the FBI on its “capture of the dangerous terrorist, Angela Davis".

On January 5, 1971, after several months in jail, Davis appeared at the Marin County Superior Court and declared her innocence before the court and nation: "I now declare publicly before the court, before the people of this country that I am innocent of all charges which have been leveled against me by the state of California." John Abt, general counsel of the Communist Party USA, was one of the first attorneys to represent Davis for her alleged involvement in the shootings.[21] While being held in the Women's Detention Center there, she was initially segregated from the general population, but with the help of her legal team soon obtained a federal court order to get out of the segregated area.[22]

Across the nation, thousands of people who agreed with her declaration began organizing a liberation movement. In New York City, black writers formed a committee called the Black People in Defense of Angela Davis. By February 1971 more than 200 local committees in the United States, and 67 in foreign countries worked to liberate Angela Davis from prison. Thanks, in part, to this support, in 1972 the state released her from county jail.[17] On February 23, 1972, Rodger McAfee, a dairy farmer from Caruthers, California, paid her $100,000 bail with the help of Steve Sparacino, a wealthy business owner. Portions of her legal defense expenses were paid for by the Presbyterian Church (UPCUSA).[17][23]

Davis was tried and the all-white jury returned a verdict of not guilty. The fact that she owned the guns used in the crime was judged not sufficient to establish her responsibility for the plot. She was represented by Leo Branton Jr., who hired psychologists to help the defense determine who in the jury pool might favor their arguments, an uncommon practice at the time, and also hired experts to undermine the reliability of eyewitness accounts.[24] Her experience as a prisoner in the US played a key role in persuading her to fight against the prison-industrial complex in the United States.[17]

John Lennon and Yoko Ono recorded their song "Angela" on their 1972 album Some Time in New York City in support. The jazz musician Todd Cochran, also known as Bayete, recorded his song "Free Angela (Thoughts...and all I've got to say)" that same year. Also in 1972, Tribe Records co-founder Phil Ranelin released a song dedicated to Davis intitled "Angela's Dilemma" on Message From The Tribe, a spiritual jazz collectable.[25] The Rolling Stones song "Sweet Black Angel", recorded in 1970 and released in 1972 on their album Exile on Main Street, is dedicated to Davis and is one of the band's few overtly political releases.[26]

In Cuba

After her release, Davis visited Cuba. In doing so she followed the precedents set by her fellow activists Robert F. Williams, Huey Newton, Stokely Carmichael, and Assata Shakur. Her reception by Afro-Cubans at a mass rally was so enthusiastic that she was reportedly barely able to speak.[27] During her stay in Cuba, Davis witnessed what she perceived to be a racism-free country. This led her to believe that “only under socialism could the fight against racism be successfully executed.” When she returned to the United States her socialist leanings increasingly influenced her understanding of race struggles within the U.S.[28]

Criticism by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn:

In a New York City speech on July 9, 1975, Russian dissident and Nobel Laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn told an AFL-CIO meeting that Davis was derelict in having failed to support prisoners in various socialist countries around the world, given her stark opposition to the U.S. prison system. He claimed a group of Czech prisoners had appealed to Davis for support, which he said she refused to offer.[29]

Solzhenitsyn stated, "Little children in school were told to sign petitions in defense of Angela Davis. Although she didn't have too difficult a time in this country's jails, she came to recuperate in Soviet resorts. Some Soviet dissidents–but more important, a group of Czech dissidents–addressed an appeal to her: 'Comrade Davis, you were in prison. You know how unpleasant it is to sit in prison, especially when you consider yourself innocent. You have such great authority now. Could you help our Czech prisoners? Could you stand up for those people in Czechoslovakia who are being persecuted by the state?' Angela Davis answered: 'They deserve what they get. Let them remain in prison.' That is the face of Communism. That is the heart of Communism for you.”[30] There are no independent reports to confirm the accuracy of this quotation that Solzhenitsyn attributed to her. In a speech at East Stroudsburg University in Pennsylvania, Davis denied Solzhenitsyn's accusations.[31]

Activism:

In 1980 and 1984, Davis ran for Vice-President along with the veteran party leader of the Communist Party, Gus Hall. However, given that the Communist Party lacked support within the US, Davis urged radicals to amass support for the Democratic Party. Revolutionaries must be realists, said Davis in a telephone interview from San Francisco where she was campaigning.[citation needed] During both of the campaigns she was Professor of Ethnic Studies at the San Francisco State University.[32] In 1979 she was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union for her civil rights activism.[citation needed] She visited Moscow in July of that year to accept the prize.

Angela Davis as honorary guest of the World Festival of Youth and Students in 1973; the banner reads "The youth of the [East] German Democratic Republic greet the youth of the world"

Davis has continued a career of activism, and has written several books. A principal focus of her current activism is the state of prisons within the United States. She considers herself an abolitionist, not a "prison reformer," and has referred to the United States prison system as the "Prison-industrial complex".[33] Davis suggested focusing social efforts on education and building "engaged communities" to solve various social problems now handled through state punishment.[2]

Davis was one of the founders of Critical Resistance, a national grassroots organization dedicated to building a movement to abolish the prison industrial complex.[34] In recent work, she argues that the prison system in the United States more closely resembles a new form of slavery than a criminal justice system. According to Davis, between the late 19th century and the mid-20th century the number of prisons in the United States sharply increased while crime rates continued to rise. During this time, the African-American population also became disproportionally represented in prisons. "What is effective or just about this "justice" system?" she urged people to question.[35]

Davis has lectured at San Francisco State University, Stanford University, Bryn Mawr College, Brown University, Syracuse University, and other schools. She states that in her teaching, which is mostly at the graduate level, she concentrates more on posing questions that encourage development of critical thinking than on imparting knowledge.[2] In 1997, she declared herself to be a lesbian in Out magazine.[36]

As early as 1969 Davis began publicly speaking, voicing her opposition to the Vietnam War, racism, sexism, and the prison industrial complex, and her support of gay rights and other social justice movements. In 1969 she blamed imperialism for the troubles suffered by oppressed populations. “We are facing a common enemy and that enemy is Yankee Imperialism, which is killing us both here and abroad. Now I think anyone who would try to separate those struggles, anyone who would say that in order to consolidate an anti-war movement, we have to leave all of these other outlying issues out of the picture, is playing right into the hands of the enemy”, she declared.[37] In 2001 she publicly spoke against the war on terror, the prison industrial complex, and the broken immigration system and told people that if they wanted to solve social justice issues they had to “hone their critical skills, develop them and implement them." Later, after the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, she declared, the “horrendous situation in New Orleans,” is due to the structures of racism, capitalism, and imperialism with which our leaders run this country.[38]

Davis opposed the 1995 Million Man March, arguing that the exclusion of women from this event necessarily promoted male chauvinism and that the organizers, including Louis Farrakhan, preferred women to take subordinate roles in society. Together with Kimberlé Crenshaw and others, she formed the African American Agenda 2000, an alliance of Black feminists.[39]

Davis is no longer a member of the Communist Party, leaving it to help found the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, which broke from the Communist Party USA because of the latter's support of the Soviet coup attempt of 1991.[40] She remains on the Advisory Board of the Committees.[41]

Davis has continued to oppose the death penalty. In 2003, she lectured at Agnes Scott College, a liberal arts women's college in Atlanta, on prison reform, minority issues, and the ills of the criminal justice system.[42]

This biographical article is written like a résumé. Please help improve it by revising it to be neutral and encyclopedic. (April 2012)

At the University of California, Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz), she participated in a 2004 panel concerning Kevin Cooper. She also spoke in defense of Stanley "Tookie" Williams on another panel in 2005,[43] and 2009.[44]

As of February 2007, Davis was teaching in the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz.[45]

In addition to being the commencement speaker at Grinnell College in 2007, in October of that year, Davis was the keynote speaker at the fifth annual Practical Activism Conference at UC Santa Cruz.[46] On February 8, 2008, Davis spoke on the campus of Howard University at the invitation of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity. On February 24, 2008, she was featured as the closing keynote speaker for the 2008 Midwest Bisexual Lesbian Gay Transgender Ally College Conference. On April 14, 2008, she spoke at the College of Charleston as a guest of the Women's and Gender Studies Program. On January 23, 2009, she was the keynote speaker at the Martin Luther King Commemorative Celebration on the campus of Louisiana State University.[47]

On April 16, 2009, she was the keynote speaker at the University of Virginia Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies symposium on The Problem of Punishment: Race, Inequity, and Justice.[48] On January 20, 2010, Davis was the keynote speaker in San Antonio, Texas, at Trinity University's MLK Day Celebration held in Laurie Auditorium. On January 21, 2011, Davis was the keynote speaker in Salem, Oregon at the Willamette University MLK Week Celebration held in Smith Auditorium where she declared that her biggest goal for the coming years is to shut down prisons. During her remarks, she also noted that while she supports some of President Barack Obama's positions, she feels he is too conservative[citation needed]. On January 27, 2011, Davis was the Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration speaker at Georgia Southern University's Performing Arts Center (PAC) in Statesboro, Georgia. On June 10, 2011, Davis delivered the Graduation Address at the Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington.[49] On May 12, 2012, Davis delivered a Commencement Address at Pitzer College, in Claremont.

On October 31, 2011, Davis spoke at the Philadelphia and Washington Square Occupy Wall Street assemblies where, due to restrictions on electronic amplification, her words were human microphoned.[50][51]

In 2012 Davis was awarded the 2011 Blue Planet Award, an award given for contributions to humanity and the planet.[52]

On March 9, 2013, Davis Spoke at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, MN about the realities of the mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex in the United States.[citation needed] She was the keynote speaker at the 18th Annual Building Bridges Conference, a conference dedicated to social justice matters.[citation needed]

On October 27, 2013 Davis appeared at the Southbank Centre, London, as the culminating speaker in a week-end of talks and concerts devoted to the 60s. It was part of "The Rest is Noise", a year-long series on 20th century cultural and political history.[53]

Teaching

Davis was a professor in the History of Consciousness and the Feminist Studies Departments at the University of California, Santa Cruz from 1991 to 2008[54] and is now Distinguished Professor Emerita.[55]

Davis was a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Syracuse University in Spring 1992[56] and October 2010.[57] She was hosted by the Women's and Gender Studies Department and the Department of African American studies.

Bibliography

If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance (New York: Third Press, 1971)

Angela Davis: An Autobiography, Random House (September 1974), ISBN 0-394-48978-0

Joan Little: The Dialectics of Rape (New York: Lang Communications, 1975)

Women, Race, & Class (February 12, 1983)

Women, Culture & Politics, Vintage (February 19, 1990), ISBN 0-679-72487-7.

The Angela Y. Davis Reader (ed. Joy James), Wiley-Blackwell (December 11, 1998), ISBN 0-631-20361-3.

Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday, Vintage Books, (January 26, 1999), ISBN 0-679-77126-3

Are Prisons Obsolete?, Open Media (April 2003), ISBN 1-58322-581-1

Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire, Seven Stories Press (October 1, 2005), ISBN 1-58322-695-8.

The Meaning of Freedom (City Lights, 2012)

Angela Davis interviews and appearances in audiovisual materials[edit]

1971

An Interview with Angela Davis. Cassette. Radio Free People, New York, 1971.

Myerson, M. "Angela Davis in Prison." Ramparts Magazine, March 1971: 20–21.

Seigner, Art. Angela Davis: Soul and Soledad. Phonodisc. Flying Dutchman, New York, 1971.

Interview with Angela Davis in San Francisco on June 1970

Walker, Joe. Angela Davis Speaks. Phonodisc. Folkways Records, New York, 1971.

1972

"Angela Davis Talks about her Future and her Freedom." Jet, July 27, 1972: 54- 57.

1977

Davis, Angela Y. I am a Black Revolutionary Woman (1971). Phonodisc. Folkways, New York, 1977.

Phillips, Esther. Angela Davis Interviews Esther Phillips. Cassette. Pacifica Tape Library, Los Angeles, 1977.

1985

Cudjoe, Selwyn. In Conversation with Angela Davis. Videocassette. ETV Center, Cornell University, Ithaca, 1985. 21 minute interview with Angela Davis.

1992

Davis, Angela Y. "Women on the Move: Travel Themes in Ma Rainey's Blues" in Borders/diasporas. Sound Recording. University of California, Santa Cruz: Center for Cultural Studies, Santa Cruz, 1992.

2000

Davis, Angela Y. The Prison Industrial Complex and its Impact on Communities of Color. Videocassette. University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, WI, 2000.

2001

Barsamian, D. "Angela Davis: African American Activist on Prison-Industrial Complex." Progressive 65.2 (2001): 33–38.

2002

"September 11 America: an Interview with Angela Davis." Policing the National Body: Sex, Race, and Criminalization. Cambridge, Ma.: South End Press, 2002.

Archives[edit]

The National United Committee to Free Angela Davis is at the Main Library at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California (A collection of thousands of letters received by the Committee and Davis from people in the US and other countries.)

The complete transcript of her trial, including all appeals and legal memoranda, have been preserved in the Meiklejohn Civil Liberties Library in Berkeley, California.

See also[edit]

Biography portal

African American portal

Communism portal

Africana philosophy

References[edit]

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis, Sweetheart of the Far Left, Finds Her Mr. Right". People. July 21, 1980. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

^ Jump up to: a b c d "Interview with Angela Davis". BookTV. 2004-10-03.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Rocks". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ Aptheker, Bettina (1999). The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (2nd ed.). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Jump up ^ Kum-Kum Bhavnani, Bhavnani; Davis,Angela (Spring 1989). "Complexity, Activism, Optimism: An Interview with Angela Y. Davis". Feminist Review (31): 66–81. JSTOR 1395091.

Jump up ^ Horowitz, David (November 10, 2006). "The Political Is Personal". Front Page Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

Jump up ^ "Sandiegoreader.com". Sandiegoreader.com. 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Waters". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Flames". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ ""Women Outlaws: Politics of Gender and Resistance in the US Criminal Justice System", SUNY Cortland, Mechthild Nagel". Web.cortland.edu. 2005-05-02. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Jump up ^ Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

Jump up ^ Google Books. Google Books. 1972-05-25. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Jump up ^ By WOLFGANG SAXONPublished: April 14, 1997 (1997-04-14). "Jerry Pacht, 75, Retired Judge Who Served on Screening Panel - New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Jump up ^ Turner, Wallace (April 28, 2011). "California Regents Drop Communist From Faculty". The New York Times.

Jump up ^ Davies, Lawrence (April 28, 2011). "U.C.L.A Teacher is Ousted as Red". The New York Times.

Jump up ^ "UCLA Barred from Pressing Red's Ouster". The New York Times. April 28, 2011.

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Aptheker, Bettina (1997). The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis. Cornell University Press.

^ Jump up to: a b "Search broadens for Angela Davis". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. August 17, 1970. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

Jump up ^ "Biography". Davis (Angela) Legal Defense Collection, 1970–1972. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

Jump up ^ Charleton, Linda (April 28, 2011). "F.B.I Seizes Angela Davisin Motel Here". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

Jump up ^ Abt, John; Myerson, Michael (1993). Advocate and Activist: Memoirs of an American Communist Lawyer. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02030-8.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Nets". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ Sol Stern (June 27, 1971). "The Campaign to Free Angela Davis and Ruchell Magee". The New York Times.

Jump up ^ William Yardley (April 27, 2013). "Leo Branton Jr., Activists' Lawyer, Dies at 91". New York Times (US). Retrieved 2013-05-23.

Jump up ^ "Message From The Tribe" Tribe Records AR 2506.

Jump up ^ Song Review by Steve Kurutz. "Sweet Black Angel – The Rolling Stones". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Jump up ^ Gott, Richard (2004). Cuba: A New History. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 230. ISBN 0-300-10411-1.

Jump up ^ Sawyer, Mark (2006). Racial politics in Post-Revolutionary Cuba. Los Angeles: University of California. pp. 95–97.

Jump up ^ Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (October 1976). Warning to the West. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-374-51334-1.

Jump up ^ Iannone, Carol (January 12, 2007). "Martin Luther King Week". The National Review.

Jump up ^ Angela Davis, Q&A after a speech, "Engaging Diversity on Campus: The Curriculum and the Faculty", East Stroudsburg University, Pennsylvania, October 15, 2006.

Jump up ^ Brooke, James (July 29, 1984). "Other Women Seeking Number 2 Spot Speak Out". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela (September 10, 1998). "Masked racism: reflections on the prison industrial complex". Color Lines.

Jump up ^ Tim Phillips, "On the Birthday of Angela Davis, the New York Times Promotes More Profiling and Police", Activist Defense, January 26, 2013.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela (2003). Are prisons Obsolete?. Canada: Open Media Series.

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis". Notable name database. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela. "Speech by Angela Davis at a Black Panther Rally in Bobby Hutton Park". Speech. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis making a live public speech (YouTube)". Speech.

Jump up ^ E. Frances White (2001). Dark continent of our bodies: black feminism and the politics of respectability. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-880-0.

Jump up ^ Lind, Amy; Stephanie Brzuzy (2008). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 406. ISBN 0-313-34038-2. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

Jump up ^ "Advisory board". Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism website. Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. 2007-07-20. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

Jump up ^ "ASC Spotlight–Africana Studies". Agnesscott.edu. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

Jump up ^ ""Angela Davis: "The State of California May Have Extinguished the Life of Stanley Tookie Williams, But They Have Not Managed to Extinguish the Hope for a Better World"", Democracy Now, December 13, 2005". Democracynow.org. 2005-12-13. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Jump up ^ Bybee, Crystal (2009-11-11). "Indybay.org". Indybay.org. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Jump up ^ NOW on PBS (February 23, 2007). "NOW on the News with Maria Hinojosa: Angela Davis on Race in America". NOW. Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

Jump up ^ Santa Cruz Indymedia coverage of the 5th annual Practical Activism Conference at UC Santa Cruz.

Jump up ^ Foley, Melissa. "LSU to Hold Martin Luther King Jr. Celebration Events". LSU Highlights. January 2009. Web. November 3, 2009. [1]

Jump up ^ Bromley, Anne. "Angela Davis to Headline the Woodson Institute's Spring Symposium". The Woodson Institute Newsletter. April 2, 2009. Web. November 3, 2009. [2]

Jump up ^ "2011 Graduation Guest Speaker at Evergreen". Evergreen.edu. May 24, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

Jump up ^ Nation of Change, Washington Square assembly.

Jump up ^ "YouTube of Occupy Philly address". Youtube.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Jump up ^ "Censure award for TEPCO Award to be handed over in Tokyo to those responsible for Fukushima (Ethecon)". financegreenwatch.org. June 22, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis". Southbank Centre. 2013-10-27. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis". Brittanica. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis". UC Santa Cruz. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

Jump up ^ "Watson Professorship". Syracuse University. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

Jump up ^ "Davis to Lecture". Syracuse University Press Office. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Angela Davis.

Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Angela Davis

Angela Davis at the Internet Movie Database

Angela Davis at AllRovi

Film clip, Davis speaking at Florida A&M University's Black History Month convocation, 1979

Davis quotations gathered by Black History Daily

A PBS interview

Round table discussion on "Resisting the Prison Industrial Complex, with Davis as a guest

New York Times archive of Davis-related articles

Time chat-room users interview with Davis on "Attacking the 'Prison Industrial Complex." 1998

Harvard Gazette article, March 13, 2003

Davis timeline at UCLA

Audio recording of Davis at a Practical Activism Conference in Santa Cruz in 2007

Guardian interview with Davis, November 8, 2007

Davis entry in the Encyclopedia of Alabama

Angela Davis on the 40th Anniversary of Her Arrest and President Obama's First Two Years – video interview by Democracy Now!

Angela Davis Biography, The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany

In Depth interview with Davis, October 3, 2004

January 26, 1944 (age 70)

Birmingham, Alabama, U.S.

Alma mater Brandeis University, B.A.

UC San Diego, M.A.

Humboldt University, Ph.D.

Occupation Educator, author, activist

Employer UC Santa Cruz (retired)

Political party

Communist Party USA (1969–1991), Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (1991–currently)

Spouse(s) Hilton Braithwaite[1]

Relatives Ben Davis (brother); Reginald Davis (brother); Fania Davis Jordan (sister)

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, scholar, Communist and author. She emerged as a nationally prominent counterculture activist and radical in the 1960s, as a leader of the Communist Party USA, and had close relations with the Black Panther Party through her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement despite never being an official member of the party. Prisoner rights have been among her continuing interests; she is the founder of Critical Resistance, an organization working to abolish the prison-industrial complex. She is a retired professor with the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and is the former director of the university's Feminist Studies department.[2]

Her research interests are in feminism, African-American studies, critical theory, Marxism, popular music, social consciousness, and the philosophy and history of punishment and prisons. Her membership in the Communist Party led to Ronald Reagan's request in 1969 to have her barred from teaching at any university in the State of California. She was tried and acquitted of suspected involvement in the Soledad brothers' August 1970 abduction and murder of Judge Harold Haley in Marin County, California. She was twice a candidate for Vice President on the Communist Party USA ticket during the 1980s.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Education

2.1 Brandeis University

2.2 University of Frankfurt

2.3 Postgraduate work

3 University of California, Los Angeles

4 Arrest and trial

5 In Cuba

6 Criticism by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

7 Activism

8 Teaching

9 Bibliography

9.1 Angela Davis interviews and appearances in audiovisual materials

9.2 Archives

10 See also

11 References

12 External links

Early life

Davis was born in Birmingham, Alabama. Her father, Frank Davis, was a graduate of St. Augustine's College, a historically black college in Raleigh, North Carolina, and was briefly a high school history teacher. Her father later owned and operated a service station in the black section of Birmingham. Her mother, Sallye Davis, a graduate of Miles College in Birmingham, was an elementary school teacher.

The family lived in the "Dynamite Hill" neighborhood, which was marked by racial conflict. Davis was occasionally able to spend time on her uncle's farm and with friends in New York City.[3] Her brother, Ben Davis, played defensive back for the Cleveland Browns and Detroit Lions in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Davis also has another brother, Reginald Davis, and sister, Fania Davis Jordan.[4]

Davis attended Carrie A. Tuggle School, a black elementary school; later she attended Parker Annex, a middle-school branch of Parker High School in Birmingham. During this time Davis' mother was a national officer and leading organizer of the Southern Negro Congress, an organization heavily influenced by the Communist Party. Consequently Davis grew up surrounded by communist organizers and thinkers who significantly influenced her intellectual development growing up.[5] By her junior year, she had applied to and was accepted at an American Friends Service Committee program that placed black students from the South in integrated schools in the North. She chose Elisabeth Irwin High School in Greenwich Village in New York City. There she was introduced to socialism and communism and was recruited by a Communist youth group, Advance. She also met children of some of the leaders of the Communist Party USA, including her lifelong friend, Bettina Aptheker.[6]

Education[edit]

Brandeis University

Davis was awarded a scholarship to Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, where she was one of three black students in her freshman class. She initially felt alienated by the isolation of the campus (at that time she was interested in Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre), but she soon made friends with foreign students. She encountered the Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse at a rally during the Cuban Missile Crisis and then became his student. In a television interview, she said "Herbert Marcuse taught me that it was possible to be an academic, an activist, a scholar, and a revolutionary."[7] She worked part-time to earn enough money to travel to France and Switzerland before she went on to attend the eighth World Festival of Youth and Students in Helsinki, Finland. She returned home in 1963 to a Federal Bureau of Investigation interview about her attendance at the Communist-sponsored festival.[8]

During her second year at Brandeis, she decided to major in French and continued her intensive study of Sartre. Davis was accepted by the Hamilton College Junior Year in France Program. Classes were initially at Biarritz and later at the Sorbonne. In Paris, she and other students lived with a French family. It was at Biarritz that she received news of the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, committed by the members of the Ku Klux Klan, an occasion that deeply affected her, because, she wrote, she was personally acquainted with the young victims.[8]

Nearing completion of her degree in French, Davis realized her major interest was in philosophy instead. She became particularly interested in the ideas of Herbert Marcuse and on her return to Brandeis she sat in on his course. Marcuse, she wrote, turned out to be approachable and helpful. Davis began making plans to attend the University of Frankfurt for graduate work in philosophy. In 1965 she graduated magna cum laude, a member of Phi Beta Kappa.[8]

University of Frankfurt

In Germany, with a stipend of $100 a month, she first lived with a German family. Later, she moved with a group of students into a loft in an old factory. After visiting East Berlin during the annual May Day celebration, she felt that the East German government was dealing better with the residual effects of fascism than were the West Germans. Many of her roommates were active in the radical Socialist German Student Union (SDS), and Davis participated in SDS actions, but events unfolding in the United States, including the formation of the Black Panther Party and the transformation of SNCC, encouraged her to return to the U.S.[8]

Postgraduate work

Marcuse, in the meantime, had moved to the University of California, San Diego, and Davis followed him there after her two years in Frankfurt.[8]

Returning to the United States, Davis stopped in London to attend a conference on "The Dialectics of Liberation." The black contingent at the conference included the American Stokely Carmichael and the British Michael X. Although moved by Carmichael's fiery rhetoric, she was disappointed by her colleagues' black nationalist sentiments and their rejection of communism as a "white man's thing." She held the view that any nationalism was a barrier to grappling with the underlying issue, capitalist domination of working people of all races.[9]

Davis earned her master's degree from the San Diego campus and her doctorate in philosophy from Humboldt University in East Berlin.[10]

University of California, Los Angeles[edit]

Davis was an acting assistant professor in the philosophy department at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), beginning in 1969. Although both Princeton and Swarthmore had expressed interest in having her join their respective philosophy departments, she opted for UCLA because of its urban location.[11] At that time, she also was known as a radical feminist and activist, a member of the Communist Party USA and an associate of the Black Panther Party.[2]

The Board of Regents of the University of California, urged by then-California Governor Ronald Reagan, fired her from her $10,000 a year post in 1969 because of her membership in the Communist Party. The Board of Regents was censured by the American Association of University Professors for their failure to reappoint Davis after her teaching contract expired.[12] On October 20, when Judge Jerry Pacht ruled the Regents could not fire Davis because of her affiliations with the Communist Party, she resumed her post.[13)

The Regents, unhappy with the decision, continued to search for ways to release Davis from her position at UCLA. They finally accomplished this on June 20, 1970, when they fired Davis for the “inflammatory language” she had used on four different speeches. “We deem particularly offensive,” the report said, “such utterances as her statement that the regents ‘killed, brutalized (and) murdered' the People's Park demonstrators, and her repeated characterizations of the police as ‘pigs.'”[14][15][16]

Arrest and trial

See also: Marin County courthouse incident

On August 7, 1970, Jonathan Jackson, a heavily armed, 17-year-old African-American high-school student, gained control over a courtroom in Marin County, California. Once in the courtroom, Jackson armed the black defendants and took Judge Harold Haley, the prosecutor, and three female jurors as hostages.[17][18] As Jackson transported the hostages and two black convicts away from the courtroom, the police began shooting at the vehicle. The judge and the three black men were killed in the melee; one of the jurors and the prosecutor were injured. Davis had purchased the firearms used in the attack, including the shotgun used to kill Haley, which had been bought two days prior and the barrel sawed off.[18] Since California considers “all persons concerned in the commission of a crime, whether they directly commit the act constituting the offense... principals in any crime so committed,” San Marin County Superior Judge Peter Allen Smith charged Davis with “aggravated kidnapping and first degree murder in the death of Judge Harold Haley” and issued a warrant for her arrest. Hours after the judge issued the warrant on August 14, 1970 a massive attempt to arrest Angela Davis began. On August 18, 1970, four days after the initial warrant was issued, the FBI director J. Edgar Hoover made Angela Davis the third woman and the 309th person to appear on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List.[17][19]

Soon after, Davis became a fugitive and fled California. According to her autobiography, during this time she hid in friends' homes and moved from place to place at night. On October 13, 1970, FBI agents found her at the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge in New York City.[20] President Richard M. Nixon congratulated the FBI on its “capture of the dangerous terrorist, Angela Davis".

On January 5, 1971, after several months in jail, Davis appeared at the Marin County Superior Court and declared her innocence before the court and nation: "I now declare publicly before the court, before the people of this country that I am innocent of all charges which have been leveled against me by the state of California." John Abt, general counsel of the Communist Party USA, was one of the first attorneys to represent Davis for her alleged involvement in the shootings.[21] While being held in the Women's Detention Center there, she was initially segregated from the general population, but with the help of her legal team soon obtained a federal court order to get out of the segregated area.[22]

Across the nation, thousands of people who agreed with her declaration began organizing a liberation movement. In New York City, black writers formed a committee called the Black People in Defense of Angela Davis. By February 1971 more than 200 local committees in the United States, and 67 in foreign countries worked to liberate Angela Davis from prison. Thanks, in part, to this support, in 1972 the state released her from county jail.[17] On February 23, 1972, Rodger McAfee, a dairy farmer from Caruthers, California, paid her $100,000 bail with the help of Steve Sparacino, a wealthy business owner. Portions of her legal defense expenses were paid for by the Presbyterian Church (UPCUSA).[17][23]

Davis was tried and the all-white jury returned a verdict of not guilty. The fact that she owned the guns used in the crime was judged not sufficient to establish her responsibility for the plot. She was represented by Leo Branton Jr., who hired psychologists to help the defense determine who in the jury pool might favor their arguments, an uncommon practice at the time, and also hired experts to undermine the reliability of eyewitness accounts.[24] Her experience as a prisoner in the US played a key role in persuading her to fight against the prison-industrial complex in the United States.[17]

John Lennon and Yoko Ono recorded their song "Angela" on their 1972 album Some Time in New York City in support. The jazz musician Todd Cochran, also known as Bayete, recorded his song "Free Angela (Thoughts...and all I've got to say)" that same year. Also in 1972, Tribe Records co-founder Phil Ranelin released a song dedicated to Davis intitled "Angela's Dilemma" on Message From The Tribe, a spiritual jazz collectable.[25] The Rolling Stones song "Sweet Black Angel", recorded in 1970 and released in 1972 on their album Exile on Main Street, is dedicated to Davis and is one of the band's few overtly political releases.[26]

In Cuba

After her release, Davis visited Cuba. In doing so she followed the precedents set by her fellow activists Robert F. Williams, Huey Newton, Stokely Carmichael, and Assata Shakur. Her reception by Afro-Cubans at a mass rally was so enthusiastic that she was reportedly barely able to speak.[27] During her stay in Cuba, Davis witnessed what she perceived to be a racism-free country. This led her to believe that “only under socialism could the fight against racism be successfully executed.” When she returned to the United States her socialist leanings increasingly influenced her understanding of race struggles within the U.S.[28]

Criticism by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn:

In a New York City speech on July 9, 1975, Russian dissident and Nobel Laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn told an AFL-CIO meeting that Davis was derelict in having failed to support prisoners in various socialist countries around the world, given her stark opposition to the U.S. prison system. He claimed a group of Czech prisoners had appealed to Davis for support, which he said she refused to offer.[29]

Solzhenitsyn stated, "Little children in school were told to sign petitions in defense of Angela Davis. Although she didn't have too difficult a time in this country's jails, she came to recuperate in Soviet resorts. Some Soviet dissidents–but more important, a group of Czech dissidents–addressed an appeal to her: 'Comrade Davis, you were in prison. You know how unpleasant it is to sit in prison, especially when you consider yourself innocent. You have such great authority now. Could you help our Czech prisoners? Could you stand up for those people in Czechoslovakia who are being persecuted by the state?' Angela Davis answered: 'They deserve what they get. Let them remain in prison.' That is the face of Communism. That is the heart of Communism for you.”[30] There are no independent reports to confirm the accuracy of this quotation that Solzhenitsyn attributed to her. In a speech at East Stroudsburg University in Pennsylvania, Davis denied Solzhenitsyn's accusations.[31]

Activism:

In 1980 and 1984, Davis ran for Vice-President along with the veteran party leader of the Communist Party, Gus Hall. However, given that the Communist Party lacked support within the US, Davis urged radicals to amass support for the Democratic Party. Revolutionaries must be realists, said Davis in a telephone interview from San Francisco where she was campaigning.[citation needed] During both of the campaigns she was Professor of Ethnic Studies at the San Francisco State University.[32] In 1979 she was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union for her civil rights activism.[citation needed] She visited Moscow in July of that year to accept the prize.

Angela Davis as honorary guest of the World Festival of Youth and Students in 1973; the banner reads "The youth of the [East] German Democratic Republic greet the youth of the world"

Davis has continued a career of activism, and has written several books. A principal focus of her current activism is the state of prisons within the United States. She considers herself an abolitionist, not a "prison reformer," and has referred to the United States prison system as the "Prison-industrial complex".[33] Davis suggested focusing social efforts on education and building "engaged communities" to solve various social problems now handled through state punishment.[2]

Davis was one of the founders of Critical Resistance, a national grassroots organization dedicated to building a movement to abolish the prison industrial complex.[34] In recent work, she argues that the prison system in the United States more closely resembles a new form of slavery than a criminal justice system. According to Davis, between the late 19th century and the mid-20th century the number of prisons in the United States sharply increased while crime rates continued to rise. During this time, the African-American population also became disproportionally represented in prisons. "What is effective or just about this "justice" system?" she urged people to question.[35]

Davis has lectured at San Francisco State University, Stanford University, Bryn Mawr College, Brown University, Syracuse University, and other schools. She states that in her teaching, which is mostly at the graduate level, she concentrates more on posing questions that encourage development of critical thinking than on imparting knowledge.[2] In 1997, she declared herself to be a lesbian in Out magazine.[36]

As early as 1969 Davis began publicly speaking, voicing her opposition to the Vietnam War, racism, sexism, and the prison industrial complex, and her support of gay rights and other social justice movements. In 1969 she blamed imperialism for the troubles suffered by oppressed populations. “We are facing a common enemy and that enemy is Yankee Imperialism, which is killing us both here and abroad. Now I think anyone who would try to separate those struggles, anyone who would say that in order to consolidate an anti-war movement, we have to leave all of these other outlying issues out of the picture, is playing right into the hands of the enemy”, she declared.[37] In 2001 she publicly spoke against the war on terror, the prison industrial complex, and the broken immigration system and told people that if they wanted to solve social justice issues they had to “hone their critical skills, develop them and implement them." Later, after the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, she declared, the “horrendous situation in New Orleans,” is due to the structures of racism, capitalism, and imperialism with which our leaders run this country.[38]

Davis opposed the 1995 Million Man March, arguing that the exclusion of women from this event necessarily promoted male chauvinism and that the organizers, including Louis Farrakhan, preferred women to take subordinate roles in society. Together with Kimberlé Crenshaw and others, she formed the African American Agenda 2000, an alliance of Black feminists.[39]

Davis is no longer a member of the Communist Party, leaving it to help found the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, which broke from the Communist Party USA because of the latter's support of the Soviet coup attempt of 1991.[40] She remains on the Advisory Board of the Committees.[41]

Davis has continued to oppose the death penalty. In 2003, she lectured at Agnes Scott College, a liberal arts women's college in Atlanta, on prison reform, minority issues, and the ills of the criminal justice system.[42]

This biographical article is written like a résumé. Please help improve it by revising it to be neutral and encyclopedic. (April 2012)

At the University of California, Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz), she participated in a 2004 panel concerning Kevin Cooper. She also spoke in defense of Stanley "Tookie" Williams on another panel in 2005,[43] and 2009.[44]

As of February 2007, Davis was teaching in the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz.[45]

In addition to being the commencement speaker at Grinnell College in 2007, in October of that year, Davis was the keynote speaker at the fifth annual Practical Activism Conference at UC Santa Cruz.[46] On February 8, 2008, Davis spoke on the campus of Howard University at the invitation of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity. On February 24, 2008, she was featured as the closing keynote speaker for the 2008 Midwest Bisexual Lesbian Gay Transgender Ally College Conference. On April 14, 2008, she spoke at the College of Charleston as a guest of the Women's and Gender Studies Program. On January 23, 2009, she was the keynote speaker at the Martin Luther King Commemorative Celebration on the campus of Louisiana State University.[47]

On April 16, 2009, she was the keynote speaker at the University of Virginia Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies symposium on The Problem of Punishment: Race, Inequity, and Justice.[48] On January 20, 2010, Davis was the keynote speaker in San Antonio, Texas, at Trinity University's MLK Day Celebration held in Laurie Auditorium. On January 21, 2011, Davis was the keynote speaker in Salem, Oregon at the Willamette University MLK Week Celebration held in Smith Auditorium where she declared that her biggest goal for the coming years is to shut down prisons. During her remarks, she also noted that while she supports some of President Barack Obama's positions, she feels he is too conservative[citation needed]. On January 27, 2011, Davis was the Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration speaker at Georgia Southern University's Performing Arts Center (PAC) in Statesboro, Georgia. On June 10, 2011, Davis delivered the Graduation Address at the Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington.[49] On May 12, 2012, Davis delivered a Commencement Address at Pitzer College, in Claremont.

On October 31, 2011, Davis spoke at the Philadelphia and Washington Square Occupy Wall Street assemblies where, due to restrictions on electronic amplification, her words were human microphoned.[50][51]

In 2012 Davis was awarded the 2011 Blue Planet Award, an award given for contributions to humanity and the planet.[52]

On March 9, 2013, Davis Spoke at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, MN about the realities of the mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex in the United States.[citation needed] She was the keynote speaker at the 18th Annual Building Bridges Conference, a conference dedicated to social justice matters.[citation needed]

On October 27, 2013 Davis appeared at the Southbank Centre, London, as the culminating speaker in a week-end of talks and concerts devoted to the 60s. It was part of "The Rest is Noise", a year-long series on 20th century cultural and political history.[53]

Teaching

Davis was a professor in the History of Consciousness and the Feminist Studies Departments at the University of California, Santa Cruz from 1991 to 2008[54] and is now Distinguished Professor Emerita.[55]

Davis was a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Syracuse University in Spring 1992[56] and October 2010.[57] She was hosted by the Women's and Gender Studies Department and the Department of African American studies.

Bibliography

If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance (New York: Third Press, 1971)

Angela Davis: An Autobiography, Random House (September 1974), ISBN 0-394-48978-0

Joan Little: The Dialectics of Rape (New York: Lang Communications, 1975)

Women, Race, & Class (February 12, 1983)

Women, Culture & Politics, Vintage (February 19, 1990), ISBN 0-679-72487-7.

The Angela Y. Davis Reader (ed. Joy James), Wiley-Blackwell (December 11, 1998), ISBN 0-631-20361-3.

Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday, Vintage Books, (January 26, 1999), ISBN 0-679-77126-3

Are Prisons Obsolete?, Open Media (April 2003), ISBN 1-58322-581-1

Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire, Seven Stories Press (October 1, 2005), ISBN 1-58322-695-8.

The Meaning of Freedom (City Lights, 2012)

Angela Davis interviews and appearances in audiovisual materials[edit]

1971

An Interview with Angela Davis. Cassette. Radio Free People, New York, 1971.

Myerson, M. "Angela Davis in Prison." Ramparts Magazine, March 1971: 20–21.

Seigner, Art. Angela Davis: Soul and Soledad. Phonodisc. Flying Dutchman, New York, 1971.

Interview with Angela Davis in San Francisco on June 1970

Walker, Joe. Angela Davis Speaks. Phonodisc. Folkways Records, New York, 1971.

1972

"Angela Davis Talks about her Future and her Freedom." Jet, July 27, 1972: 54- 57.

1977

Davis, Angela Y. I am a Black Revolutionary Woman (1971). Phonodisc. Folkways, New York, 1977.

Phillips, Esther. Angela Davis Interviews Esther Phillips. Cassette. Pacifica Tape Library, Los Angeles, 1977.

1985

Cudjoe, Selwyn. In Conversation with Angela Davis. Videocassette. ETV Center, Cornell University, Ithaca, 1985. 21 minute interview with Angela Davis.

1992

Davis, Angela Y. "Women on the Move: Travel Themes in Ma Rainey's Blues" in Borders/diasporas. Sound Recording. University of California, Santa Cruz: Center for Cultural Studies, Santa Cruz, 1992.

2000

Davis, Angela Y. The Prison Industrial Complex and its Impact on Communities of Color. Videocassette. University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, WI, 2000.

2001

Barsamian, D. "Angela Davis: African American Activist on Prison-Industrial Complex." Progressive 65.2 (2001): 33–38.

2002

"September 11 America: an Interview with Angela Davis." Policing the National Body: Sex, Race, and Criminalization. Cambridge, Ma.: South End Press, 2002.

Archives[edit]

The National United Committee to Free Angela Davis is at the Main Library at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California (A collection of thousands of letters received by the Committee and Davis from people in the US and other countries.)

The complete transcript of her trial, including all appeals and legal memoranda, have been preserved in the Meiklejohn Civil Liberties Library in Berkeley, California.

See also[edit]

Biography portal

African American portal

Communism portal

Africana philosophy

References[edit]

Jump up ^ "Angela Davis, Sweetheart of the Far Left, Finds Her Mr. Right". People. July 21, 1980. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

^ Jump up to: a b c d "Interview with Angela Davis". BookTV. 2004-10-03.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Rocks". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ Aptheker, Bettina (1999). The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (2nd ed.). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Jump up ^ Kum-Kum Bhavnani, Bhavnani; Davis,Angela (Spring 1989). "Complexity, Activism, Optimism: An Interview with Angela Y. Davis". Feminist Review (31): 66–81. JSTOR 1395091.

Jump up ^ Horowitz, David (November 10, 2006). "The Political Is Personal". Front Page Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

Jump up ^ "Sandiegoreader.com". Sandiegoreader.com. 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Waters". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Flames". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ ""Women Outlaws: Politics of Gender and Resistance in the US Criminal Justice System", SUNY Cortland, Mechthild Nagel". Web.cortland.edu. 2005-05-02. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Jump up ^ Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

Jump up ^ Google Books. Google Books. 1972-05-25. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

Jump up ^ By WOLFGANG SAXONPublished: April 14, 1997 (1997-04-14). "Jerry Pacht, 75, Retired Judge Who Served on Screening Panel - New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Jump up ^ Turner, Wallace (April 28, 2011). "California Regents Drop Communist From Faculty". The New York Times.

Jump up ^ Davies, Lawrence (April 28, 2011). "U.C.L.A Teacher is Ousted as Red". The New York Times.

Jump up ^ "UCLA Barred from Pressing Red's Ouster". The New York Times. April 28, 2011.

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Aptheker, Bettina (1997). The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis. Cornell University Press.

^ Jump up to: a b "Search broadens for Angela Davis". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. August 17, 1970. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

Jump up ^ "Biography". Davis (Angela) Legal Defense Collection, 1970–1972. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

Jump up ^ Charleton, Linda (April 28, 2011). "F.B.I Seizes Angela Davisin Motel Here". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

Jump up ^ Abt, John; Myerson, Michael (1993). Advocate and Activist: Memoirs of an American Communist Lawyer. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02030-8.

Jump up ^ Davis, Angela Yvonne (March 1989). "Nets". Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0667-7.

Jump up ^ Sol Stern (June 27, 1971). "The Campaign to Free Angela Davis and Ruchell Magee". The New York Times.

Jump up ^ William Yardley (April 27, 2013). "Leo Branton Jr., Activists' Lawyer, Dies at 91". New York Times (US). Retrieved 2013-05-23.

Jump up ^ "Message From The Tribe" Tribe Records AR 2506.

Jump up ^ Song Review by Steve Kurutz. "Sweet Black Angel – The Rolling Stones". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Jump up ^ Gott, Richard (2004). Cuba: A New History. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 230. ISBN 0-300-10411-1.

Jump up ^ Sawyer, Mark (2006). Racial politics in Post-Revolutionary Cuba. Los Angeles: University of California. pp. 95–97.

Jump up ^ Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (October 1976). Warning to the West. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-374-51334-1.

Jump up ^ Iannone, Carol (January 12, 2007). "Martin Luther King Week". The National Review.