“...The work of African American cultural critic, NYU professor, and film historian Clyde R. Taylor, whose extraordinary book The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract—Film & Literature (Indiana University Press, 1998) is a major, groundbreaking advance in U.S. cultural studies, poetics, and critical theory, is crucial to a fresh perspective and analysis of this highly complex subject. In his book Taylor aggressively takes on the present crisis of knowledge in the United States by directly engaging in a historically informed critique of the aesthetic from a breathtaking interrogation of its many theoretical, ideological, and political uses in Western literature, film, painting, sculpture, and philosophy since the Renaissance, with a special emphasis on investigating and analyzing these uses and the myriad counter-modalities of radical resistance, opposition, and self-determining alternatives within the context of 20th century America. This necessarily brief survey cannot possibly do justice to the profound contributions that Dr. Taylor makes to our understanding and knowledge of the meaning of the “cultural politics of representation” and the political economy of art, but it does indicate that in the past forty years alongside such original and exciting contemporary African American thinkers, writers, artists and critics as Greg Tate, Nathaniel Mackey, Imani Perry, Yusef Komunyakaa, Paul Beatty, Harryette Mullen, Tricia Rose, Erica Hunt, DJ Spooky (aka Paul Miller), Brent Hayes Edwards, Will Alexander, Fred Moten, Robin D. G. Kelley, Nelson George, bell hooks, Robert O'Meally, Mark Anthony Neal, Kara Walker, Saidiya Hartman, George E. Lewis, Steve Coleman, Frank B. Wilderson III, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michelle Wallace, Jayne Cortez, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed, Julius Hemphill, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Tyshawn

Sorey Wadada Leo Smith, Muhal Richard Abrams, Charles Mills, and Kevin Young, among many others a strikingly new sensibility is making itself known. One that simultaneously embraces, critiques, and goes far beyond previous myopic and ultimately reductive white and black modernist notions of the ‘avant-garde.’…”

–From the introduction to What is An Aesthetic?: Writings On American Culture (1980-Present) by Kofi Natambu. © 2024

Clyde Taylor, Literary Scholar Who Elevated Black Cinema, Dies at 92

A leading figure in the field of Black studies in the 1970s, he identified work by Black filmmakers as worthy of serious intellectual attention.

A leading figure in the field of Black studies in the 1970s, he identified work by Black filmmakers as worthy of serious intellectual attention.

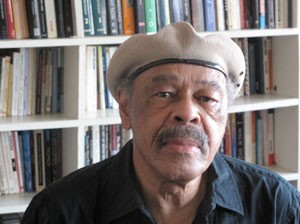

PHOTO: Clyde Taylor in the 1970s, when he was at the epicenter of a push to bring the study of Black culture into academia. Credit: via Taylor family

by Clay Risen

February 6, 2024

New York Times

Clyde Taylor, a scholar who in the 1970s and ’80s played a leading role in identifying, defining and elevating Black cinema as an art form, died on Jan. 24 at his home in Los Angeles. He was 92.

His daughter, Rahdi Taylor, a filmmaker, said the cause was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

As a young professor in the Los Angeles area in the late 1960s — first at California State University, Long Beach, and then at the University of California, Los Angeles — Dr. Taylor was at the epicenter of a push to bring the study of Black culture into academia.

Black culture was not merely an appendage to white culture, he argued, but had its own logic, history and dynamics that grew out of the Black Power and Pan-African movements. And filmmaking, he said, was just as important to Black culture as literature and art.

by Clay Risen

February 6, 2024

New York Times

Clyde Taylor, a scholar who in the 1970s and ’80s played a leading role in identifying, defining and elevating Black cinema as an art form, died on Jan. 24 at his home in Los Angeles. He was 92.

His daughter, Rahdi Taylor, a filmmaker, said the cause was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

As a young professor in the Los Angeles area in the late 1960s — first at California State University, Long Beach, and then at the University of California, Los Angeles — Dr. Taylor was at the epicenter of a push to bring the study of Black culture into academia.

Black culture was not merely an appendage to white culture, he argued, but had its own logic, history and dynamics that grew out of the Black Power and Pan-African movements. And filmmaking, he said, was just as important to Black culture as literature and art.

Dr. Taylor in 1958 when he was a student at Howard University, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English. Credit: via Taylor family

He was especially taken by the work of a circle of young Black filmmakers in the 1970s that he would later call the “L.A. Rebellion.” Among them were the directors Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Haile Gerima and Billy Woodberry, all of whom went on to have immense impact on Black directors like Spike Lee and Ava DuVernay.

As Dr. Taylor documented, these directors created their own, stripped-down approach to narrative and form. They borrowed from French New Wave, Italian neorealism and Brazil’s Cinema Novo to offer an unblinkered look at everyday Black life, often filming in Watts and other Black neighborhoods in and around Los Angeles.

“He was doing the work on the ground, discovering new filmmakers and bringing them into the academic conversation,” Ellen Scott, a professor of film studies at U.C.L.A., said in a phone interview.

To these directors, film was more than just art; it was a tool that used the camera to illuminate the ways in which racial disparities shaped the lives of Black Americans.

Dr. Taylor praised their work as a vital part of the revolutionary changes underway across Black America. In an essay accompanying a 1986 exhibit on Black filmmakers at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York, he wrote that their “bold, even extravagant innovation sought filmic equivalents of Black social and cultural discourse.”

“These young filmmakers made a commitment to dramatic films,” he added, “a commitment fired by the discomfort of dwelling in the belly of the beast: Minutes away, Hollywood was reviving itself economically through a glut of mercenary Black exploitation movies.”

Clyde Russell Taylor was born on July 3, 1931, in Boston, the youngest of eight children. Both parents were active in the civil rights movement. His father, Frank Taylor, was a Pullman train porter and a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, one of the country’s largest Black unions; his mother, E. Alice (Tyson) Taylor, was an entrepreneur and a longtime board member of the N.A.A.C.P.’s Boston chapter.

Dr. Taylor attended Howard University, receiving a bachelor’s degree in English in 1953 and a master’s in the subject in 1959. Howard was the country’s premier historically Black university, and he met a long list of future artistic luminaries there, including the novelist Toni Morrison and the playwright Amiri Baraka.

He also fell under the sway of one of Howard’s leading intellectual lights, the philosopher Alain Locke, whose concept of “the New Negro” and promotion of Blackness as a social and cultural category helped shape the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s — and would later prove influential to Dr. Taylor’s own work.

He was especially taken by the work of a circle of young Black filmmakers in the 1970s that he would later call the “L.A. Rebellion.” Among them were the directors Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Haile Gerima and Billy Woodberry, all of whom went on to have immense impact on Black directors like Spike Lee and Ava DuVernay.

As Dr. Taylor documented, these directors created their own, stripped-down approach to narrative and form. They borrowed from French New Wave, Italian neorealism and Brazil’s Cinema Novo to offer an unblinkered look at everyday Black life, often filming in Watts and other Black neighborhoods in and around Los Angeles.

“He was doing the work on the ground, discovering new filmmakers and bringing them into the academic conversation,” Ellen Scott, a professor of film studies at U.C.L.A., said in a phone interview.

To these directors, film was more than just art; it was a tool that used the camera to illuminate the ways in which racial disparities shaped the lives of Black Americans.

Dr. Taylor praised their work as a vital part of the revolutionary changes underway across Black America. In an essay accompanying a 1986 exhibit on Black filmmakers at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York, he wrote that their “bold, even extravagant innovation sought filmic equivalents of Black social and cultural discourse.”

“These young filmmakers made a commitment to dramatic films,” he added, “a commitment fired by the discomfort of dwelling in the belly of the beast: Minutes away, Hollywood was reviving itself economically through a glut of mercenary Black exploitation movies.”

Clyde Russell Taylor was born on July 3, 1931, in Boston, the youngest of eight children. Both parents were active in the civil rights movement. His father, Frank Taylor, was a Pullman train porter and a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, one of the country’s largest Black unions; his mother, E. Alice (Tyson) Taylor, was an entrepreneur and a longtime board member of the N.A.A.C.P.’s Boston chapter.

Dr. Taylor attended Howard University, receiving a bachelor’s degree in English in 1953 and a master’s in the subject in 1959. Howard was the country’s premier historically Black university, and he met a long list of future artistic luminaries there, including the novelist Toni Morrison and the playwright Amiri Baraka.

He also fell under the sway of one of Howard’s leading intellectual lights, the philosopher Alain Locke, whose concept of “the New Negro” and promotion of Blackness as a social and cultural category helped shape the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s — and would later prove influential to Dr. Taylor’s own work.

Dr. Taylor in 2010. His extensive work in the academic world and beyond made him a lodestar for generations of younger scholars. Credit: via Taylor family

He attended Wayne State University in Detroit for his doctorate, which he received in 1968 with a dissertation on the English poet and painter William Blake.

By then he was teaching at California State University, Long Beach, where he became chairman of the Black studies department in 1969. He later taught at U.C.L.A.; the University of California, Berkeley; Stanford; and Mills College (now a part of Northeastern University) in Oakland, Calif., before moving east to Tufts in 1982. He retired from N.Y.U. in 2008.

Dr. Taylor married JoAnn Spencer in 1960; they divorced in 1970. His second marriage, to Marti Wilson, also ended in divorce. Along with his daughter Ms. Taylor, he is survived by a granddaughter. Another daughter, Shelley Zinzi Taylor, died in 2007.

Although he wrote just one major book, “The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract — Film and Literature” (1998), Dr. Taylor was prolific in other ways.

With Beth Deare, he wrote the script for the documentary “Midnight Ramble” (1994), about the early Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. He also curated several major museum exhibits, wrote extensively in journals like Jump Cut and Black Film Review, and appeared as a commentator in documentaries about Black actors like Paul Robeson and Sidney Poitier.

Such work made him a lodestar for generations of younger scholars, and a gravitational center of Black cultural studies even today.

“You have to deal with Clyde if you talk about Black cinema,” Manthia Diawara, a professor of film studies at New York University, said by phone, “just as you have to deal with certain people if you talk about African-American literature.”

Clay Risen is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk. More about Clay Risen

A version of this article appears in print on Feb. 8, 2024, Section B, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: Clyde Taylor, 92, Scholar Who Elevated Black Cinema. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

https://amsterdamnews.com/news/2024/02/13/eminent-literary-and-film-scholar-dr-clyde-taylor-dies-at-92/

Obits

He attended Wayne State University in Detroit for his doctorate, which he received in 1968 with a dissertation on the English poet and painter William Blake.

By then he was teaching at California State University, Long Beach, where he became chairman of the Black studies department in 1969. He later taught at U.C.L.A.; the University of California, Berkeley; Stanford; and Mills College (now a part of Northeastern University) in Oakland, Calif., before moving east to Tufts in 1982. He retired from N.Y.U. in 2008.

Dr. Taylor married JoAnn Spencer in 1960; they divorced in 1970. His second marriage, to Marti Wilson, also ended in divorce. Along with his daughter Ms. Taylor, he is survived by a granddaughter. Another daughter, Shelley Zinzi Taylor, died in 2007.

Although he wrote just one major book, “The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract — Film and Literature” (1998), Dr. Taylor was prolific in other ways.

With Beth Deare, he wrote the script for the documentary “Midnight Ramble” (1994), about the early Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. He also curated several major museum exhibits, wrote extensively in journals like Jump Cut and Black Film Review, and appeared as a commentator in documentaries about Black actors like Paul Robeson and Sidney Poitier.

Such work made him a lodestar for generations of younger scholars, and a gravitational center of Black cultural studies even today.

“You have to deal with Clyde if you talk about Black cinema,” Manthia Diawara, a professor of film studies at New York University, said by phone, “just as you have to deal with certain people if you talk about African-American literature.”

Clay Risen is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk. More about Clay Risen

A version of this article appears in print on Feb. 8, 2024, Section B, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: Clyde Taylor, 92, Scholar Who Elevated Black Cinema. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

https://amsterdamnews.com/news/2024/02/13/eminent-literary-and-film-scholar-dr-clyde-taylor-dies-at-92/

Obits

Eminent literary and film scholar Dr. Clyde Taylor dies at 92

by Herb Boyd

February 13, 2024

Amsterdam News

PHOTO: Clyde Taylor courtesy of NYU Gallatin School

“We live in days of Great Change, a shuffling of status and symbols,” Dr. Clyde Taylor wrote in 1973. “Yeats’ cry ‘Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold’ is good news in the Third World; a ferment rises in the young bloods in the bush. And stepping out of the shelter of their place in the shadows of American exceptionalist rationalizations.”

Taylor, an example of the activist scholars of his day, composed this as part of an essay about “Black Consciousness in the Vietnam Years,” reflective of his stance against the Vietnam War. That strong voice of the Black liberation movement took a final breath on January 24. He was 92 and died in Los Angeles. According to his daughter, Rahdi Taylor, the cause of his death was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Born Clyde Russell Taylor on July 3, 1931, in Boston, he was the youngest of eight children of his parents, Frank and E. Alice (Tyson) Taylor. His father was a member of the legendary Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and his mother was an entrepreneur who was active with the NAACP’s Boston chapter.

Not much is known of Taylor’s formative years, although we do know that he was a graduate of English High School and later Howard University, where he received his B.A. degree in 1953 and six years later, his master’s in the same subject. It was there that he met several Black literary and political activists, including Toni Morrison and Amiri Baraka.

After graduation from Howard, Taylor enlisted in the Air Force as an intelligence officer and left service as a first lieutenant; he was honorably discharged with a National Defense Service Medal. At Wayne State University in Detroit, he earned his doctorate with a dissertation on the works of William Blake and the ideology of art. In 1960, he married JoAnn Spencer and they had two daughters, Rahdi and Shelley Zinzi Taylor. They divorced in 1970.

Two years later, Taylor moved to San Francisco and married Martella Wilson. Together, they founded the African Film Society. By the mid-’90s, the marriage had dissolved. Taylor moved to New York City and began teaching at New York University.

Throughout these turbulent times, Taylor was on the ramparts of the Black studies movement, particularly at UCLA, with a critical role in advancing revolutionary cinema, most notably as a presenter and commentator: “The making of ‘O Povo Organizado’ [‘The People Organized’] in Mozambique by Bob Van Lierop, an African American, or of ‘Sambizanga,’ about Angola by Guadoupian Sara Maldoror, or the Ethiopian Haile Gerima’s ‘Bush Mama,’ set in Los Angeles, or Pontecorvo’s ‘The Battle of Algiers,’ or the several Latin American and African films created by Cubans, or the many Third World films made by Europeans and white Americans––all suggest the cross-fertilizations of an embryonic transnational Third World cinema movement.” Taylor figured prominently in this development.

A book certainly could have been forged from Taylor’s extensive study of cinema, and one was published: “The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract––Film and Literature in 1988.”

In one of his last essays, Taylor expounded on the differences between Africa and Hollywood: “Africa stands today (2021) at the other end of the spectrum from Hollywood. If Americans view cinema from the center of profitable, monopolistic production and distribution, Africa is a laboratory for the study of film’s relation to society from the vantage point of the exploited.”

Right down to the end of his extraordinary life, Clyde Taylor possessed a keen analysis and passionate commitment to the world of cinema and its prospects here and abroad.

https://gallatin.nyu.edu/news/2024/02/clyde-taylor--nyu-gallatin-professor-emeritus--passes-away.html

Taylor, an example of the activist scholars of his day, composed this as part of an essay about “Black Consciousness in the Vietnam Years,” reflective of his stance against the Vietnam War. That strong voice of the Black liberation movement took a final breath on January 24. He was 92 and died in Los Angeles. According to his daughter, Rahdi Taylor, the cause of his death was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Born Clyde Russell Taylor on July 3, 1931, in Boston, he was the youngest of eight children of his parents, Frank and E. Alice (Tyson) Taylor. His father was a member of the legendary Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and his mother was an entrepreneur who was active with the NAACP’s Boston chapter.

Not much is known of Taylor’s formative years, although we do know that he was a graduate of English High School and later Howard University, where he received his B.A. degree in 1953 and six years later, his master’s in the same subject. It was there that he met several Black literary and political activists, including Toni Morrison and Amiri Baraka.

After graduation from Howard, Taylor enlisted in the Air Force as an intelligence officer and left service as a first lieutenant; he was honorably discharged with a National Defense Service Medal. At Wayne State University in Detroit, he earned his doctorate with a dissertation on the works of William Blake and the ideology of art. In 1960, he married JoAnn Spencer and they had two daughters, Rahdi and Shelley Zinzi Taylor. They divorced in 1970.

Two years later, Taylor moved to San Francisco and married Martella Wilson. Together, they founded the African Film Society. By the mid-’90s, the marriage had dissolved. Taylor moved to New York City and began teaching at New York University.

Throughout these turbulent times, Taylor was on the ramparts of the Black studies movement, particularly at UCLA, with a critical role in advancing revolutionary cinema, most notably as a presenter and commentator: “The making of ‘O Povo Organizado’ [‘The People Organized’] in Mozambique by Bob Van Lierop, an African American, or of ‘Sambizanga,’ about Angola by Guadoupian Sara Maldoror, or the Ethiopian Haile Gerima’s ‘Bush Mama,’ set in Los Angeles, or Pontecorvo’s ‘The Battle of Algiers,’ or the several Latin American and African films created by Cubans, or the many Third World films made by Europeans and white Americans––all suggest the cross-fertilizations of an embryonic transnational Third World cinema movement.” Taylor figured prominently in this development.

A book certainly could have been forged from Taylor’s extensive study of cinema, and one was published: “The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract––Film and Literature in 1988.”

In one of his last essays, Taylor expounded on the differences between Africa and Hollywood: “Africa stands today (2021) at the other end of the spectrum from Hollywood. If Americans view cinema from the center of profitable, monopolistic production and distribution, Africa is a laboratory for the study of film’s relation to society from the vantage point of the exploited.”

Right down to the end of his extraordinary life, Clyde Taylor possessed a keen analysis and passionate commitment to the world of cinema and its prospects here and abroad.

https://gallatin.nyu.edu/news/2024/02/clyde-taylor--nyu-gallatin-professor-emeritus--passes-away.html

Clyde Taylor, NYU Gallatin Professor Emeritus, Passes Away

February 12, 2024

New York University

February 12, 2024

New York University

Clyde Taylor, Professor Emeritus at the NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study, and a scholar whose work was integral to elevating Black cinema as an art form, died on January 24, 2024. He was 92.

At the beginning of his career as a professor in the late 1960s in the Los Angeles area, Dr. Taylor was a leader in bringing the study of Black culture, including Black film, into the academy. He saw Black culture as having its own logic, history, and dynamics, and he felt that filmmaking was as integral to Black culture as art and literature. According to e. Frances White, Professor Emerita of Individualized Study and former Dean at Gallatin, "Dr. Taylor's work on Black cinema helped students and young filmmakers see a way to produce Black art when there appeared to be no way for them to express themselves."

Dr. Taylor was especially intrigued by a group of young Black filmmakers in the 1970s that included Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Billy Woodberry, and Haile Gerima. A circle he would come to call the “LA Rebellion,” these directors innovated their own approach to narrative and form—an approach that would eventually have an outsized impact on the likes of Ava DuVernay and Spike Lee.

Dr. Taylor joined the NYU Gallatin community in the Fall of 1997 having already established himself as a pioneer in the field of Black Cinema Studies. As an exemplar of the School’s interdisciplinary approach to teaching, learning, and research, his interests ranged from art criticism and curation to political theory and social movements, from literature to epistemology, and so much more. Founding Gallatin Professor Emerita Sharon Friedman shares that Dr. Taylor “was always challenging us to think more adventurously,” an apt reflection on his own academic range.

The courses he taught at Gallatin were a wonderful showcase of this range, with such titles as “Slavery and Culture in the US and Brazil,” “Narratives of African Civilization,” and “Modernism and Imperialism: Objects of Transcultural Desire.” Dr. Taylor’s professional work also highlighted his broad focus of scholarship, inquiry, and exploration. His book The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract - Film and Literature (1998) is a cornerstone text across disciplines, as are his edited collections Vietnam and Black America (1973) and Black Genius (2000), his documentary on Oscar Micheaux (1994), and his curation of exhibits at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Brooklyn Museum.

Following Dr. Taylor’s retirement in 2008, and in recognition of his contributions to the School and the fields he helped define, Gallatin created the Clyde Taylor Award for Distinguished Work in African-American and Africana Studies. This honor is offered to one graduating BA student and one graduating MA student each year to recognize their high-caliber work in African American or Africana Studies.

We at Gallatin were fortunate to benefit from Dr. Taylor’s groundbreaking work, scholarship, and teaching, and we join his loved ones and those who he impacted in celebrating his life and mourning his loss.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clyde_Taylor

Dr. Clyde Taylor

1931-2024

Born

July 3, 1931

Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

Died

January 24, 2024 (aged 92)

Los Angeles, California, U.S.

Citizenship: American

Occupation(s): Film scholar, writer, and cultural critic

Children: 2

Clyde Russell Taylor (July 3, 1931 – January 24, 2024) was an American film scholar, writer and cultural critic who made contributions to the fields of cinema studies and African American studies. He was an emeritus professor at New York University. His scholarship and commentary often focused on Black film and culture.

Career

Clyde Taylor wrote and published numerous scholarly articles, essays, and reviews.[1] Taylor is best known for coining the term 'L.A. Rebellion', which refers to the group of African American filmmakers who emerged from the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television in the 1970s.[2][3][4] This movement was characterized by its emphasis on social realism and its rejection of Hollywood conventions.

Clyde held faculty positions at UC Berkeley, Stanford University, and Mills College, then returned to Boston for a position in the Department of English at Tufts University.[5][6][7] After over a decade at Tufts University, Taylor accepted a position at New York University.[8] He remained at NYU in the Gallatin School of Individualized Study and the Department of Africana Studies, until he retired, Professor Emeritus in 2008.

Taylor was the author of the book, The Mask of Art: Breaking the Aesthetic Contract – Film and Literature (Indiana University Press, 1998), which was awarded the PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award in 1999.[9][10] He co-wrote the screenplay for Midnight Ramble, a seminal feature documentary about the work and legacy of Oscar Micheaux released by American Experience on PBS in 1995.[11] He was a frequent contributor to journals such as Black Film Review and Jump Cut.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Other accolades for Taylor included induction into the National Literary Hall of Fame for Writers of African Descent, by the Gwendolyn Brooks Cultural Center; the 1982 Callaloo Creative Writing Award for Non-Fiction Prose, an "Indie" Award for critical writing on cinema of people of color from the Association of Independent Video and Film (AIVF); and the Richard Wright Award for Literacy Criticism from Black World.[18][19] He was the recipient of a FulbrightFellowship, as well as Fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation (Whitney Scholar-in-Residency Fellowship), the Ford Foundation Fellowship (DuBois Institute, Harvard University), the Rockefeller Foundation (Fellowship, NYU Center for Culture, Media and History), as well as two Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Early life

Clyde Taylor was born in Boston, Massachusetts on July 3, 1931, the youngest of eight children, to E. Alice Taylor and Frank Taylor. He graduated from The English High School and later from Howard University.

Once at Howard University, Clyde studied in the Department of English in collegial engagement with fellow students like Amiri Baraka and Toni Morrison. At Howard he studied under professors such as Alain LeRoy Locke. Taylor earned both Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in English.

After graduation, Taylor enlisted in the United States Air Force as an intelligence officer, earning the rank of First Lieutenant. He was honorably discharged and recognized with a National Defense Service Medal. He continued his studies, pursuing a graduate degree in English at Wayne State University in Detroit, MI. He wrote his dissertation on the works of William Blake and the Ideology of Art, and earned a Ph.D.[20]

Personal life

While at Wayne State University, he met student JoAnn Spencer from Detroit, pursuing her degree in education. They married in June 1960 in Detroit and had two children, daughters Shelley Zinzi Taylor and Rahdi Taylor. Their marriage dissolved in 1970. In 1972, Taylor moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he went on to marry Martella Wilson, a young leader in the world of philanthropy and social impact charities. Together they co-founded and led the African Film Society, which hosted screenings of cinema from Western Africa and discussions of their aesthetic and social vision. In the mid 90s, the couple dissolved the marriage but continued living and working in Boston until Taylor moved to Manhattan for a position at New York University in 1998.

Taylor died on January 24, 2024, at the age of 92.[21]