A magazine of Black politics and culture

The Gaza Strip Has Been Destroyed. So Has Hope for a Fair Future for the Two Peoples.

As a Jewish leftist born in Israel, I feel a profound sense of grief and defeat.

by Amira Hass

Hammer and Hope

No. 3

Spring, 2024

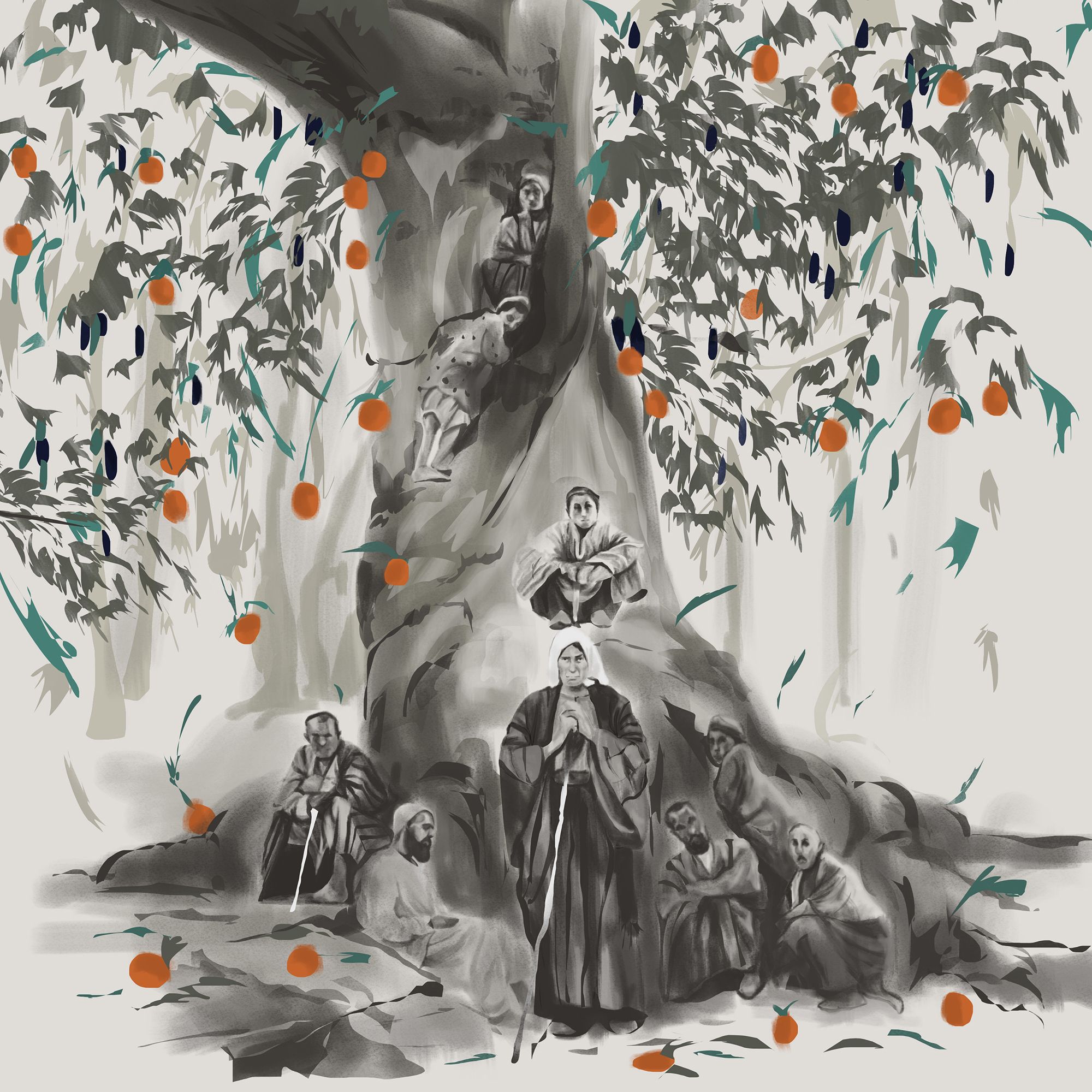

Amira Khalil, Owners of the Land, 2023.

Translated by Riva Hocherman

I write these words from the West Bank with a profound sense of grief and defeat, as the clashing terms of victory, genocide, erasure, heroic struggle, and historic achievement come up again and again in reference to the Palestinian people and to Gazans in particular.

The Gaza Strip cast a spell on me, as it did for many who visited it and came to know its people. It was an inseparable part of historic Palestine until it was cut off after the creation of the state of Israel and the expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland in 1948-49. As a result, it emerged as a distinct sociological and geopolitical entity. Its core characteristic was its high proportion of refugees (about 75 percent of its population), whose roots were in dozens of villages and towns that Israel depopulated and destroyed.

The Gaza Strip we knew as a compact geographical entity of 365 square kilometers was still large enough to contain the diversity of village and city, of new neighborhoods and old, of the shore and the hills, of poor and rich, of refugees and native-born. And it was small and crowded, so its people lived in one another’s pockets, more and more as their numbers grew, and it felt that everyone knew everyone else and there were no secrets. It was so small and tightly bound it seemed that all people living there took an active part in whatever political, social, and military events were going on.

Despite the disconnection, destruction and passage of time, the refugees of 1948 and their descendants preserved their family and social bonds and emotional attachment to their lost villages and communities. Through the shared reality of isolation and expulsion, and in the compactness of the place, the people of Gaza developed the collective hallmarks of an entirely non-imaginary, non-abstract community: side-splitting humor, warmth and hospitality, ingenuity, industry and solidarity, stubbornness and suspicion, courage and tenacity, insularity and curiosity, pride of place and a sense of injury from the scorn of others.

As the effects of the closure imposed by Israel in 1991 grew more severe over the years, turning Gaza into a vast prison facility, the industry and ingenuity were replaced by widespread apathy and inaction, alongside the emergence of resourcefulness, impressive creativity, and a vivid will to live. With all these contradictions and hardships, the Gaza Strip evolved into its own framework of belonging and patriotic loyalty while also representing all Palestinians and their cause — a kind of Palestinian microcosm — more than any other group of Palestinians.

About two years ago I wrote, “This unique framework is one of the explanations (although not the only one) for the extraordinary resilience of its people and how they have coped for decades with extreme and nightmarish situations that are hard to summon to the imagination, culminating in deathly Israeli military assaults.” At the time, I could not conceive of the horrors of the current war, which is now raging in its fifth month.

Wars are an extension of policies, and this current war is of a piece with Israel’s yearslong policy to thwart any national Palestinian project toward freedom and independence. Yet there is no denying that this war of destruction was triggered by Hamas’s attack on Oct. 7, 2023.

This attack — against Israeli soldiers and military installations, against civilians in their homes and at a dance party in nature — shattered Israel’s hubris and exposed its structural weakness as a military power. What is this weakness? It is its inability and refusal to comprehend that domination over the Palestinian people, while denying their history as an indigenous nation, their rights as a people and their freedom, is not sustainable in perpetuity. The impenetrable confidence, the arrogant certainty that it is possible to live a good and happy life while also controlling, oppressing, and imprisoning more than two million Gazans — and profiting from that oppression and exploitation — was blown up on Oct. 7 when many hundreds of Hamas militants and an unknown number of Palestinian civilians tore down the walls of the largest prison on earth, if just for a few hours. In the annals of national liberation struggles, this could certainly be seen as an achievement.

Still, my sense of defeat is strong and persistent, and it is threefold. For decades, Palestinians and left-wing activists in Israel, myself included, have warned Israelis and the states supporting Israel that ongoing oppression and ruthless domination will lead to a dreadful explosion, harmful to all, to bloodshed and intolerable suffering. But the appeal of material privileges and benefits that Israel offered Jews (both Israeli citizens and citizens of other states) who moved to the occupied Palestinian territory proved stronger. Those have included affordable villas, subsidies and tax exemptions, better education and health care, and land for agriculture and other business ventures that could be had for free or for only a symbolic price. Add to this the fact that the occupied territory has become a huge laboratory for Israel’s weapons industry and state-of-the-art surveillance technology, two of the Israeli economy’s most profitable exports. The careers and incomes of people from all walks of life are closely tied to these occupation-related industries and to the bureaucratic machinery needed for the maintenance of a repressive hostile rule imposed upon more than five million Palestinians.

Israeli Jews know that any peace agreement would require equal rights for Israel’s Palestinian citizens and either compensation or the return of their lands and property stolen by Israel in 1948, and the equal distribution of water resources between Jews and Arabs in the entire country. So the end of the occupation and equal rights are consciously or subconsciously conceived as posing a threat to the good life and well-being of many an Israeli Jew. All this has been bolstered by messianic racist theories and preaching. Such theories (including sexism) develop and spread in order to justify exploitation, discrimination of all sorts, and repression, but at a certain stage they receive a life of their own, spreading poison as they are perceived by more and more generations as irrefutable laws of nature.

We on the left, when we warned that there was nothing “natural” about ruling over another people, leaned on universal and Jewish values; we invoked historical lessons of the failure of excessive power; we tried to appeal to reason and argue that it’s in Israel’s self-interest to end the occupation — in vain. I myself have written and said more than once that we may reach a level of brutality from which there is no return.

This was a warning that I could not imagine would become a prophecy: well planned and meticulous as Hamas’s attack was militarily, it also unleashed the rage, personal and collective, stored up by thousands and their desire for vengeance on Israelis (including foreign citizens working in Israel and Palestinian citizens of Israel). The militants of the Islamic resistance movement and the Gaza civilians who joined them made no distinction between soldiers and civilians, adults and children and babies, mostly Jews but also some non-Jews. The loved ones of about 1,400 families were harmed that day, killed or taken captive. There is evidence of sexual abuse and rape as well. Thousands more were injured or escaped by the skin of their teeth. (The number of Hamas casualties from Oct. 7 are estimated at around a thousand.) It is considered to be the worst defeat and trauma to afflict Israelis since 1948.

Two days after the massacre, in great pain that has not left me since, I wrote: “In a single day, Israeli civilians endured what Palestinians have suffered for decades and continue to suffer as routine: military invasion, death, brutality, children killed, bodies dumped on the road, siege, paralyzing fear, dread for the fate of loved ones, their capture, the urge for revenge, the desire to cause mass lethal harm to those involved (militants) and not involved (civilians), inferiority, the destruction of buildings and ruin of a holiday or celebration, weakness and helplessness in the face of an all-powerful armed force, stinging humiliation. Again: We told you. Oppression and injustice without end erupt at unexpected times and places. Like pollution, bloodshed knows no boundaries.”

In its reaction, Israel acted as one could expect it to and right away commenced a vengeful genocidal campaign of devastation, which, at the time of writing, is ongoing. The number of Palestinians killed by Israeli bombing and shelling and the unimaginable scale of destruction surge each day. By the end of January, the Israeli army had slain more than 26,000 Palestinians, more than 10,000 of them children. Thousands more are missing. The number of Palestinian fighters killed in combat inside the strip is not known, and it is unclear whether they are included in the official count. At least half of all buildings in Gaza have been destroyed by bombing and fighting between the Israeli army and Hamas militants. At least two-thirds of the residents of the Gaza Strip — about 1.7 million people — have been displaced. Tens of thousands have fled their homes in the north and south of the country. So many precious lives and suffering could have been spared if they had listened. But they did not.

The second reason for my sense of defeat is less personal but no less painful: the failure of the mass popular struggle against Israeli oppression. Unlike the armed struggle, the popular unarmed revolt involves all the people: women and men, young and old, laborers, administrators, and academics, as in the 1987–91 uprising, the First Intifada, and the first days of the Second Intifada in 2000. A mass revolt that includes many social strata will inevitably be diverse and effective through different channels: mass confrontation with the occupation forces, civil disobedience against the occupation bureaucracy, cultural activities, initiatives of popular education and learning, grassroots political initiatives, popular committees of support and mutual assistance, a conscious readiness to sacrifice normal life and take risks, and broad participation in planning and developing long-term strategy. All this gives the struggle a democratic character in its essence.

It is not hard to explain the great devaluation in the status of popular struggle among Palestinians: at every turn, the great collective undertaking yielded damaged crops, politically, nationally, and on a personal level.

The First Intifada led to negotiations between Palestinians and Israel, which produced the Oslo Accords. These were defined as a peace agreement, and the Palestinians were convinced that by 1999 they would result in a small independent state alongside Israel. Although they were making a painful compromise in their willingness to accept only 22 percent of historic Palestine, they supported the accords to spare future generations the pain and deprivation of living under occupation. From the moment the accords were signed, however, Israel exploited the agreement to thwart any possibility of such a state by constructing settlements and compressing Palestinians into small enclaves within the West Bank, separating them from the Gaza enclave.

Those activists who subscribed to the principle of unarmed struggle to work against settlement expansion, together with Jewish left-wing activists, were and are subjected to harassment by Israel’s security branches, which intimidate them, carry out arrests, bring baseless charges, and deploy physical violence causing injury and even death.

Palestinians in Gaza began protesting en masse against the siege and for the right of return to their destroyed villages in 2018 and continued for more than two years. There was some throwing of stones, Molotov cocktails, and incendiary balloons that burned fields across the border, but these did not endanger human life. Yet the soldiers firing from behind the border fence killed many protesters and wounded scores more, causing permanent disabilities and loss of limbs.

Israel cast the civil campaign to impose boycott, divestment, and sanctions and international legal activism against its war crimes as motivated by pure antisemitism, while cynically using the 1939–45 genocide of Jews to force Western countries to criminalize the campaign.

The clear political message from these nonviolent efforts was rejected by Israel, and the unarmed uprising made little impact on the occupiers and the occupation. The logical step, to many Palestinians, was clear: to inflict more pain on the occupier until he understands. This was the conclusion in 2000, when the Israeli army killed unarmed demonstrators and imposed severe restrictions of movement on the entire population at the beginning of the Second Intifada. Armed Palestinian organizations, led by Hamas, returned to their tactics of the 1990s in opposing negotiations with Israel: suicide bombings on buses, in markets, and in restaurants, which killed many Israeli citizens. Over time, Hamas developed and perfected its ability to fire rockets at Israel, while sending conflicting political and religious messages about the future of the country and that of the two peoples who live in it.

Did the suicide bombings of the 1990s and the 2000s and the war of rockets succeed in stopping Israel’s settlement expansion and its drive to constrain Palestinians in enclaves while stealing more land, resources, and space? No, the opposite. They were successful as a terrifying means of vengeance, true, but they failed to stop the colonializing process. Yet the aura of armed resistance only shines brighter for many Palestinians and their supporters in the world.

This is the third reason for the sense of defeat that eats at me, as a feminist socialist: the deeply masculinist praxis of developing and producing weapons, trading them, reaping profits and unleashing them is taken as an axiom and an indisputable starting point — whether as a measure of national power, sovereignty, and the ostensible right to sanctioned violence or as a supreme, revered means of resistance to oppression. But unlike in the 16th and the 19th centuries, today’s weapons and arms and any escalating competition have the capacity to lead to the destruction of the world and humanity at large.

The Gaza Strip we knew has been destroyed and its community has been dismantled by the Israeli war machine. Israel has killed and wounded an unfathomable number of civilians. We haven’t yet begun reckoning with the trauma. The educated, the wealthy, those with connections abroad and ingenuity are leaving Gaza and will continue to leave. Reconstruction will take decades. Will we ever see some seismic political and social breakthrough that will recast this dreadful destruction and Hamas’s strategy of armed resistance as “worthwhile”? It is too early to say.

The Gaza Strip cast a spell on me, as it did for many who visited it and came to know its people. It was an inseparable part of historic Palestine until it was cut off after the creation of the state of Israel and the expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland in 1948-49. As a result, it emerged as a distinct sociological and geopolitical entity. Its core characteristic was its high proportion of refugees (about 75 percent of its population), whose roots were in dozens of villages and towns that Israel depopulated and destroyed.

The Gaza Strip we knew as a compact geographical entity of 365 square kilometers was still large enough to contain the diversity of village and city, of new neighborhoods and old, of the shore and the hills, of poor and rich, of refugees and native-born. And it was small and crowded, so its people lived in one another’s pockets, more and more as their numbers grew, and it felt that everyone knew everyone else and there were no secrets. It was so small and tightly bound it seemed that all people living there took an active part in whatever political, social, and military events were going on.

Despite the disconnection, destruction and passage of time, the refugees of 1948 and their descendants preserved their family and social bonds and emotional attachment to their lost villages and communities. Through the shared reality of isolation and expulsion, and in the compactness of the place, the people of Gaza developed the collective hallmarks of an entirely non-imaginary, non-abstract community: side-splitting humor, warmth and hospitality, ingenuity, industry and solidarity, stubbornness and suspicion, courage and tenacity, insularity and curiosity, pride of place and a sense of injury from the scorn of others.

As the effects of the closure imposed by Israel in 1991 grew more severe over the years, turning Gaza into a vast prison facility, the industry and ingenuity were replaced by widespread apathy and inaction, alongside the emergence of resourcefulness, impressive creativity, and a vivid will to live. With all these contradictions and hardships, the Gaza Strip evolved into its own framework of belonging and patriotic loyalty while also representing all Palestinians and their cause — a kind of Palestinian microcosm — more than any other group of Palestinians.

About two years ago I wrote, “This unique framework is one of the explanations (although not the only one) for the extraordinary resilience of its people and how they have coped for decades with extreme and nightmarish situations that are hard to summon to the imagination, culminating in deathly Israeli military assaults.” At the time, I could not conceive of the horrors of the current war, which is now raging in its fifth month.

Wars are an extension of policies, and this current war is of a piece with Israel’s yearslong policy to thwart any national Palestinian project toward freedom and independence. Yet there is no denying that this war of destruction was triggered by Hamas’s attack on Oct. 7, 2023.

This attack — against Israeli soldiers and military installations, against civilians in their homes and at a dance party in nature — shattered Israel’s hubris and exposed its structural weakness as a military power. What is this weakness? It is its inability and refusal to comprehend that domination over the Palestinian people, while denying their history as an indigenous nation, their rights as a people and their freedom, is not sustainable in perpetuity. The impenetrable confidence, the arrogant certainty that it is possible to live a good and happy life while also controlling, oppressing, and imprisoning more than two million Gazans — and profiting from that oppression and exploitation — was blown up on Oct. 7 when many hundreds of Hamas militants and an unknown number of Palestinian civilians tore down the walls of the largest prison on earth, if just for a few hours. In the annals of national liberation struggles, this could certainly be seen as an achievement.

Still, my sense of defeat is strong and persistent, and it is threefold. For decades, Palestinians and left-wing activists in Israel, myself included, have warned Israelis and the states supporting Israel that ongoing oppression and ruthless domination will lead to a dreadful explosion, harmful to all, to bloodshed and intolerable suffering. But the appeal of material privileges and benefits that Israel offered Jews (both Israeli citizens and citizens of other states) who moved to the occupied Palestinian territory proved stronger. Those have included affordable villas, subsidies and tax exemptions, better education and health care, and land for agriculture and other business ventures that could be had for free or for only a symbolic price. Add to this the fact that the occupied territory has become a huge laboratory for Israel’s weapons industry and state-of-the-art surveillance technology, two of the Israeli economy’s most profitable exports. The careers and incomes of people from all walks of life are closely tied to these occupation-related industries and to the bureaucratic machinery needed for the maintenance of a repressive hostile rule imposed upon more than five million Palestinians.

Israeli Jews know that any peace agreement would require equal rights for Israel’s Palestinian citizens and either compensation or the return of their lands and property stolen by Israel in 1948, and the equal distribution of water resources between Jews and Arabs in the entire country. So the end of the occupation and equal rights are consciously or subconsciously conceived as posing a threat to the good life and well-being of many an Israeli Jew. All this has been bolstered by messianic racist theories and preaching. Such theories (including sexism) develop and spread in order to justify exploitation, discrimination of all sorts, and repression, but at a certain stage they receive a life of their own, spreading poison as they are perceived by more and more generations as irrefutable laws of nature.

We on the left, when we warned that there was nothing “natural” about ruling over another people, leaned on universal and Jewish values; we invoked historical lessons of the failure of excessive power; we tried to appeal to reason and argue that it’s in Israel’s self-interest to end the occupation — in vain. I myself have written and said more than once that we may reach a level of brutality from which there is no return.

This was a warning that I could not imagine would become a prophecy: well planned and meticulous as Hamas’s attack was militarily, it also unleashed the rage, personal and collective, stored up by thousands and their desire for vengeance on Israelis (including foreign citizens working in Israel and Palestinian citizens of Israel). The militants of the Islamic resistance movement and the Gaza civilians who joined them made no distinction between soldiers and civilians, adults and children and babies, mostly Jews but also some non-Jews. The loved ones of about 1,400 families were harmed that day, killed or taken captive. There is evidence of sexual abuse and rape as well. Thousands more were injured or escaped by the skin of their teeth. (The number of Hamas casualties from Oct. 7 are estimated at around a thousand.) It is considered to be the worst defeat and trauma to afflict Israelis since 1948.

Two days after the massacre, in great pain that has not left me since, I wrote: “In a single day, Israeli civilians endured what Palestinians have suffered for decades and continue to suffer as routine: military invasion, death, brutality, children killed, bodies dumped on the road, siege, paralyzing fear, dread for the fate of loved ones, their capture, the urge for revenge, the desire to cause mass lethal harm to those involved (militants) and not involved (civilians), inferiority, the destruction of buildings and ruin of a holiday or celebration, weakness and helplessness in the face of an all-powerful armed force, stinging humiliation. Again: We told you. Oppression and injustice without end erupt at unexpected times and places. Like pollution, bloodshed knows no boundaries.”

In its reaction, Israel acted as one could expect it to and right away commenced a vengeful genocidal campaign of devastation, which, at the time of writing, is ongoing. The number of Palestinians killed by Israeli bombing and shelling and the unimaginable scale of destruction surge each day. By the end of January, the Israeli army had slain more than 26,000 Palestinians, more than 10,000 of them children. Thousands more are missing. The number of Palestinian fighters killed in combat inside the strip is not known, and it is unclear whether they are included in the official count. At least half of all buildings in Gaza have been destroyed by bombing and fighting between the Israeli army and Hamas militants. At least two-thirds of the residents of the Gaza Strip — about 1.7 million people — have been displaced. Tens of thousands have fled their homes in the north and south of the country. So many precious lives and suffering could have been spared if they had listened. But they did not.

The second reason for my sense of defeat is less personal but no less painful: the failure of the mass popular struggle against Israeli oppression. Unlike the armed struggle, the popular unarmed revolt involves all the people: women and men, young and old, laborers, administrators, and academics, as in the 1987–91 uprising, the First Intifada, and the first days of the Second Intifada in 2000. A mass revolt that includes many social strata will inevitably be diverse and effective through different channels: mass confrontation with the occupation forces, civil disobedience against the occupation bureaucracy, cultural activities, initiatives of popular education and learning, grassroots political initiatives, popular committees of support and mutual assistance, a conscious readiness to sacrifice normal life and take risks, and broad participation in planning and developing long-term strategy. All this gives the struggle a democratic character in its essence.

It is not hard to explain the great devaluation in the status of popular struggle among Palestinians: at every turn, the great collective undertaking yielded damaged crops, politically, nationally, and on a personal level.

The First Intifada led to negotiations between Palestinians and Israel, which produced the Oslo Accords. These were defined as a peace agreement, and the Palestinians were convinced that by 1999 they would result in a small independent state alongside Israel. Although they were making a painful compromise in their willingness to accept only 22 percent of historic Palestine, they supported the accords to spare future generations the pain and deprivation of living under occupation. From the moment the accords were signed, however, Israel exploited the agreement to thwart any possibility of such a state by constructing settlements and compressing Palestinians into small enclaves within the West Bank, separating them from the Gaza enclave.

Those activists who subscribed to the principle of unarmed struggle to work against settlement expansion, together with Jewish left-wing activists, were and are subjected to harassment by Israel’s security branches, which intimidate them, carry out arrests, bring baseless charges, and deploy physical violence causing injury and even death.

Palestinians in Gaza began protesting en masse against the siege and for the right of return to their destroyed villages in 2018 and continued for more than two years. There was some throwing of stones, Molotov cocktails, and incendiary balloons that burned fields across the border, but these did not endanger human life. Yet the soldiers firing from behind the border fence killed many protesters and wounded scores more, causing permanent disabilities and loss of limbs.

Israel cast the civil campaign to impose boycott, divestment, and sanctions and international legal activism against its war crimes as motivated by pure antisemitism, while cynically using the 1939–45 genocide of Jews to force Western countries to criminalize the campaign.

The clear political message from these nonviolent efforts was rejected by Israel, and the unarmed uprising made little impact on the occupiers and the occupation. The logical step, to many Palestinians, was clear: to inflict more pain on the occupier until he understands. This was the conclusion in 2000, when the Israeli army killed unarmed demonstrators and imposed severe restrictions of movement on the entire population at the beginning of the Second Intifada. Armed Palestinian organizations, led by Hamas, returned to their tactics of the 1990s in opposing negotiations with Israel: suicide bombings on buses, in markets, and in restaurants, which killed many Israeli citizens. Over time, Hamas developed and perfected its ability to fire rockets at Israel, while sending conflicting political and religious messages about the future of the country and that of the two peoples who live in it.

Did the suicide bombings of the 1990s and the 2000s and the war of rockets succeed in stopping Israel’s settlement expansion and its drive to constrain Palestinians in enclaves while stealing more land, resources, and space? No, the opposite. They were successful as a terrifying means of vengeance, true, but they failed to stop the colonializing process. Yet the aura of armed resistance only shines brighter for many Palestinians and their supporters in the world.

This is the third reason for the sense of defeat that eats at me, as a feminist socialist: the deeply masculinist praxis of developing and producing weapons, trading them, reaping profits and unleashing them is taken as an axiom and an indisputable starting point — whether as a measure of national power, sovereignty, and the ostensible right to sanctioned violence or as a supreme, revered means of resistance to oppression. But unlike in the 16th and the 19th centuries, today’s weapons and arms and any escalating competition have the capacity to lead to the destruction of the world and humanity at large.

The Gaza Strip we knew has been destroyed and its community has been dismantled by the Israeli war machine. Israel has killed and wounded an unfathomable number of civilians. We haven’t yet begun reckoning with the trauma. The educated, the wealthy, those with connections abroad and ingenuity are leaving Gaza and will continue to leave. Reconstruction will take decades. Will we ever see some seismic political and social breakthrough that will recast this dreadful destruction and Hamas’s strategy of armed resistance as “worthwhile”? It is too early to say.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Amira Hass is the Haaretz correspondent for the occupied territories. Born in Jerusalem in 1956, Hass joined Haaretz in 1989 and has been in her current position since 1993. She spent three years living in Gaza, which served as the basis for her widely acclaimed book Drinking the Sea at Gaza. She has lived in the West Bank city of Ramallah since 1997. Hass is also the author of two other books, both of which are compilations of her articles.

Hammer & Hope is free to read. Sign up for our newsletter, donate to our magazine, and follow us on Instagram, Threads, TikTok, Facebook, and Twitter.