‘Indecency has become a new hallmark’: writer and historian Jelani Cobb on race in Donald Trump’s America

In a new essay collection, the dean of Columbia University’s graduate school of journalism makes a compelling argument that everything is connected and nothing is inevitable about racial justice or democracy

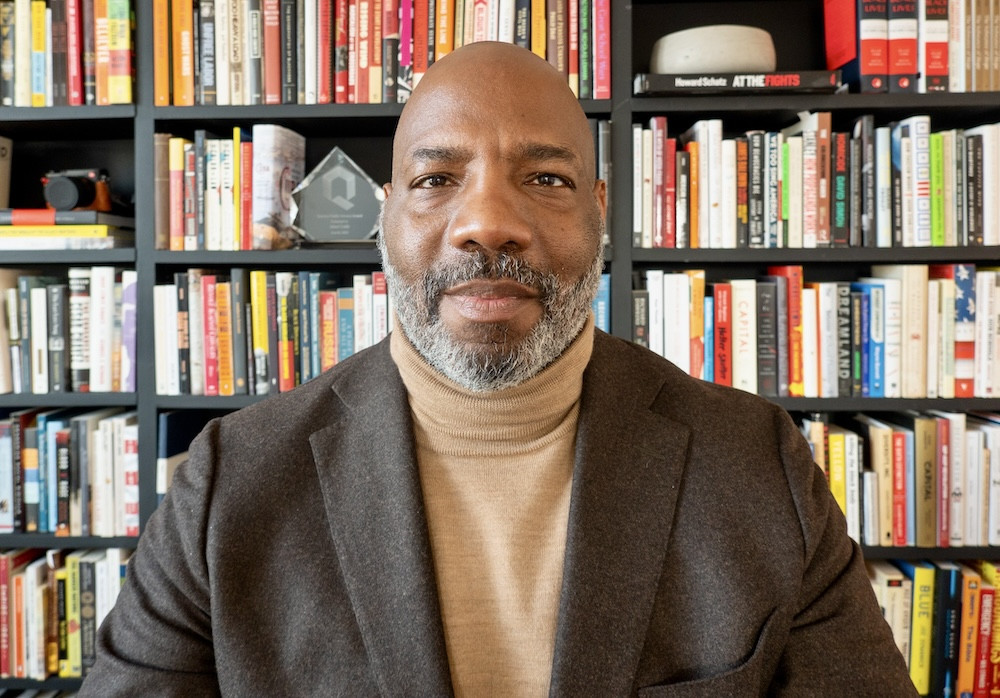

Jelani Cobb at the Obama Foundation democracy forum in New York in 2022. Photograph: Peter Foley/UPI via Alamy

“From the vantage point of the newsroom, the first story is almost never the full story,” writes Jelani Cobb. “You hear stray wisps of information, almost always the most inflammatory strands of a much bigger, more complicated set of circumstances.”

The dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in New York could be reflecting on the recent killing of the racist provocateur Charlie Kirk. In fact, he is thinking back to Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African American student from Florida who was shot dead by a white Latino neighbourhood watch volunteer in 2012.

“The Martin case – the nightmare specter of a lynching screaming across the void of history – ruined the mood of a nation that had, just a few years earlier, elected its first black president, and in a dizzying moment of self-congratulation, began to ponder on editorial pages whether the nation was now ‘post-racial’,” Cobb writes in the introduction to his book Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here: 2012-2025.

Many of the essays in the collection were written contemporaneously, affording them the irony – sometimes bitter irony – of distance. Together they form a portrait of an era bookended by the killing of Martin and the return to power of Donald Trump, with frontline reporting from Ferguson and Minneapolis along the way. They make a compelling argument that everything is connected and nothing is inevitable about racial justice or democracy.

As Cobb chronicles across 437 pages, the 2013 acquittal of Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman, became a catalyst for conversations about racial profiling, gun laws and systemic racism, helping to inspire the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Three years later, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old white supremacist, attended a Bible study session at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, then opened fire and killed nine Black parishioners. Cobb notes that Roof told police he had been “radicalised” by the aftermath of Martin’s killing and wanted to start a “race war”.

“From the vantage point of the newsroom, the first story is almost never the full story,” writes Jelani Cobb. “You hear stray wisps of information, almost always the most inflammatory strands of a much bigger, more complicated set of circumstances.”

The dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in New York could be reflecting on the recent killing of the racist provocateur Charlie Kirk. In fact, he is thinking back to Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African American student from Florida who was shot dead by a white Latino neighbourhood watch volunteer in 2012.

“The Martin case – the nightmare specter of a lynching screaming across the void of history – ruined the mood of a nation that had, just a few years earlier, elected its first black president, and in a dizzying moment of self-congratulation, began to ponder on editorial pages whether the nation was now ‘post-racial’,” Cobb writes in the introduction to his book Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here: 2012-2025.

Many of the essays in the collection were written contemporaneously, affording them the irony – sometimes bitter irony – of distance. Together they form a portrait of an era bookended by the killing of Martin and the return to power of Donald Trump, with frontline reporting from Ferguson and Minneapolis along the way. They make a compelling argument that everything is connected and nothing is inevitable about racial justice or democracy.

As Cobb chronicles across 437 pages, the 2013 acquittal of Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman, became a catalyst for conversations about racial profiling, gun laws and systemic racism, helping to inspire the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Three years later, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old white supremacist, attended a Bible study session at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, then opened fire and killed nine Black parishioners. Cobb notes that Roof told police he had been “radicalised” by the aftermath of Martin’s killing and wanted to start a “race war”.

Jelani Cobb’s Three or More Is a Riot. Photograph: One World

Speaking by phone from his office at Columbia, Cobb, 56, says: “It was a very upside-down version of the facts because he looked on Martin’s death and somehow took the reaction to it as a threat to white people and that was what set him on his path. Roof was this kind of precursor of the cause of white nationalism and white supremacy that becomes so prominent now.”

Then, in the pandemic-racked summer of 2020, came George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man murdered by a white police officer who kneeled on his neck for almost nine minutes as Floyd said, “I can’t breathe,” more than 20 times. Black Lives Matter protesters took to the streets with demands to end police brutality, invest in Black communities and address systemic racism across various institutions.

Cobb, an author, historian and staff writer at the New Yorker magazine, continues: “It was the high tide. A lot of the organising, a lot of the kinds of thinking, the perspective and the work and the cultural kinds of representations – these things had begun eight years earlier with Trayvon Martin’s death.

“This was an excruciating, nearly nine-minute-long video of a person’s life being extinguished and it happened at a time when people had nothing to do but watch it. They weren’t able to go to work because people were in lockdown. All of those things made his death resonate in a way that it might not have otherwise. There had been egregious instances of Black people being killed prior to that and they hadn’t generated that kind of societal response.”

Cities such as Minneapolis, Seattle and Los Angeles reallocated portions of police budgets to community programmes; companies committed millions of dollars to racial-equity initiatives; for a time, discussions of systemic racism entered mainstream discourse. But not for the first time in US history, progress – or at least the perception of it – sowed the seeds of backlash.

“It also was a signal for people who are on the opposite side of this to start pushing in the opposite direction and that happened incredibly swiftly and with incredible consequences to such an extent that we are now in a more reactionary place than we were when George Floyd died in the first place,” Cobb says.

No one better embodies that reactionary spirit than Donald Trump, who rose to political prominence pushing conspiracy theories about Barack Obama’s birthplace and demonising immigrants as criminals and rapists. His second term has included a cabinet dominated by white people and a purge of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Trump lost the presidential election a few months after Floyd died but returned to power last year, defeating a Black and south Asian challenger in Kamala Harris. According to Pew Research, Trump made important gains with Latino voters (51% Harris, 48% Trump) and won 15% of Black voters – up from 8% in 2020.

What does Cobb make of the notion that class now outweighs race in electoral politics? “One of the things that they did brilliantly was that typically politics has worked on the basis of: ‘What will you do for me?’” Cobb says. “That’s retail politics. That’s what you expect.

“The Trump campaign in 24 was much more contingent upon the question of: ‘What will you do to people who I don’t like?’ There were some Black men who thought their marginal position in society was a product of the advances that women made and that was something the Republican party said overtly, which is why I think their appeal was so masculinist.”

Trump and his allies weaponised prejudice against transgender people to attract socially and religiously conservative voters, including demographics they would otherwise hold in “contempt”. “I also think that we tended to overlook the question of the extent to which Joe Biden simply handing the nomination to Kamala Harris turned off a part of the electorate,” Cobb says.

He expresses frustration with the well-rehearsed argument that Democrats became too fixated on “woke” identity politics at the expense of economic populism: “They make it seem as if these groups created identity politics. Almost every group that’s in the Democratic fold was made into an identity group by the actions of people who were outside.

“If you were talking about African Americans, Black politics was created by segregation. White people said that they were going to act in their interest in order to prevent African Americans from having access. Women, through the call of feminism, came to address the fact that they were excluded from politics because men wanted more power. You could go through every single group.”

Yet it remains commonplace to talk about appealing to evangelical Christian voters or working-class non-college-educated voters, he says: “The presumption implicit in this is that all those people see the world in a particular way that is understandable or legible by their identity, and so there’s a one-sidedness to it. For the entirety of his political career, Trump has simply been a shrewd promulgator of white-identity politics.”

That trend has become supercharged in Trump’s second term. He has amplified the great replacement theory, sought to purge diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and complained that museums over-emphasise slavery. His actions have built a permission structure for white nationalists who boast they now have a seat at the top table.

Many observers have also expressed dismay at Trump’s concentration of executive power and the speed and scale of his assault on democratic institutions. Cobb, however, is not surprised.

“It’s about what I expected, honestly,” he says, “because throughout the course of the 2024 campaign, Trump mainly campaigned on the promises of what he was going to do to get back at people. They’re using the power of the state to pursue personal and ideological grievances, which is what autocracy does.”

It is now fashionable on the left to bemoan the rise of US authoritarianism as a novel concept, a betrayal of constitutional ideals envied by the world. Cobb has a more complex take, suggesting that the US’s claim to moral primacy, rooted in the idea of exceptionalism, is based on a false premise.

‘Who has ever managed personal growth while constantly screaming to the world about how special and amazing they are?’

Jelani Cobb

He argues: “America has been autocratic previously. We just don’t think about it. It’s never been useful … to actually grapple with what America was, and America had no interest in grappling with these questions itself. Who has ever managed personal growth while constantly screaming to the world about how special and amazing they are?”

Cobb’s book maps an arc of the moral universe that is crooked and uneven, pointing out that, between the end of reconstruction and 1965, 11 states in the south effectively nullified the protections of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments of the constitution, imposing Jim Crow laws, voter suppression and violence to disenfranchise Black citizens.

“The constitution gave Black people the right to vote but, if you voted, you’d be killed and this was a known fact,” he says. “This went on for decade after decade after decade. You can call that a lot of things. You can’t call that democracy. It was a kind of racial autocracy that extended in lots of different directions.”

He adds: “We should have been mindful that the country could always return to form in that way, that its commitment to democracy had been tenuous. That was why race has played such a central role in the dawning of this current autocratic moment. But it’s not the only dynamic.

“Immigration, which is tied to race in some ways, is another dynamic. The advances that women have made, the increasing acceptance and tolerance of people in the LGBTQ communities – all those things, combined with an economic tenuousness, have made it possible to just catalyse this resurgence of autocracy in the country.”

It is therefore hardly unexpected that business leaders and institutions would capitulate, as they have in the past, he says: “We might hope that they would react differently but it’s not a shock when they don’t. Go back to the McCarthy era. We see that in more instances than not, McCarthy and other similar kinds of red-baiting forces were able to exert their will on American institutions.”

Cobb’s own employer has been caught in the maelstrom. In February, the Trump administration froze $400m in federal research grants and funding to Columbia, citing the university’s “failure to protect Jewish students from antisemitic harassment” during Gaza protests last year. Columbia has since announced it would comply with nearly all the administration’s demands and agreed to a $221m settlement, restoring most frozen funds but with ongoing oversight.

Cobb does not have much to add, partly for confidentiality reasons, though he does comment: “In life, I have tended to not grade harshly for exams that people should never have been required to take in the first place.”

He is unwavering, however, in his critique of Trump’s attack on the university sector: “What’s happening is people emulating Viktor Orbán [the leader of Hungary] to try to crush any independent centres of dissent and to utilise the full weight of the government to do it, and also to do it in hypocritical fashion.

“The cover story was that Columbia and other universities were being punished for their failure to uproot antisemitism on their campuses. But it’s difficult to understand how you punish an institution for being too lenient about antisemitism and the punishment is that you take away its ability to do cancer research, or you defund its ability to do research on the best medical protocols for sick children or to work on heart disease and all the things that were being done with the money that was taken from the university.

“In fact, what is being done is that we are criminalising the liberal or progressive ideas and centres that are tolerant of people having a diverse array of ideas or progressive ideas. The irony, of course, is that one of the things that happens in autocracy is the supreme amount of hypocrisy. They have an incredible tolerance for hypocrisy and so all these things are being done under the banner of protecting free speech.”

That hypocrisy has been on extravagant display again in the aftermath of Kirk’s killing by a lone gunman on a university campus in Utah. Trump and his allies have been quick to blame the “radical left” and “domestic terrorists” and threaten draconian action against those who criticise Kirk or celebrate his demise. The response is only likely to deepen the US’s political polarisation and threat of further violence.

Spencer Cox, the governor of Utah and a rare voice urging civil discourse, wondered whether this was the end of a dark chapter of US history – or the beginning. What does Cobb think? “There’s a strong possibility that it will get worse before it gets better,” he says frankly.

“We’re at a point where we navigated the volatile moment of the 1950s, the 1960s, because we were able to build a social consensus around what we thought was decent and what we thought was right, and we’re now seeing that undone. Indecency has become a new hallmark.

“But we should take some solace in the fact that people have done the thing that we need to do now previously. The situation we’re in I don’t think is impossible.”

Explore more on these topics:

Columbia University

US constitution and civil liberties

Race

US politics

interviews

Speaking by phone from his office at Columbia, Cobb, 56, says: “It was a very upside-down version of the facts because he looked on Martin’s death and somehow took the reaction to it as a threat to white people and that was what set him on his path. Roof was this kind of precursor of the cause of white nationalism and white supremacy that becomes so prominent now.”

Then, in the pandemic-racked summer of 2020, came George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man murdered by a white police officer who kneeled on his neck for almost nine minutes as Floyd said, “I can’t breathe,” more than 20 times. Black Lives Matter protesters took to the streets with demands to end police brutality, invest in Black communities and address systemic racism across various institutions.

Cobb, an author, historian and staff writer at the New Yorker magazine, continues: “It was the high tide. A lot of the organising, a lot of the kinds of thinking, the perspective and the work and the cultural kinds of representations – these things had begun eight years earlier with Trayvon Martin’s death.

“This was an excruciating, nearly nine-minute-long video of a person’s life being extinguished and it happened at a time when people had nothing to do but watch it. They weren’t able to go to work because people were in lockdown. All of those things made his death resonate in a way that it might not have otherwise. There had been egregious instances of Black people being killed prior to that and they hadn’t generated that kind of societal response.”

Cities such as Minneapolis, Seattle and Los Angeles reallocated portions of police budgets to community programmes; companies committed millions of dollars to racial-equity initiatives; for a time, discussions of systemic racism entered mainstream discourse. But not for the first time in US history, progress – or at least the perception of it – sowed the seeds of backlash.

“It also was a signal for people who are on the opposite side of this to start pushing in the opposite direction and that happened incredibly swiftly and with incredible consequences to such an extent that we are now in a more reactionary place than we were when George Floyd died in the first place,” Cobb says.

No one better embodies that reactionary spirit than Donald Trump, who rose to political prominence pushing conspiracy theories about Barack Obama’s birthplace and demonising immigrants as criminals and rapists. His second term has included a cabinet dominated by white people and a purge of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Trump lost the presidential election a few months after Floyd died but returned to power last year, defeating a Black and south Asian challenger in Kamala Harris. According to Pew Research, Trump made important gains with Latino voters (51% Harris, 48% Trump) and won 15% of Black voters – up from 8% in 2020.

What does Cobb make of the notion that class now outweighs race in electoral politics? “One of the things that they did brilliantly was that typically politics has worked on the basis of: ‘What will you do for me?’” Cobb says. “That’s retail politics. That’s what you expect.

“The Trump campaign in 24 was much more contingent upon the question of: ‘What will you do to people who I don’t like?’ There were some Black men who thought their marginal position in society was a product of the advances that women made and that was something the Republican party said overtly, which is why I think their appeal was so masculinist.”

Trump and his allies weaponised prejudice against transgender people to attract socially and religiously conservative voters, including demographics they would otherwise hold in “contempt”. “I also think that we tended to overlook the question of the extent to which Joe Biden simply handing the nomination to Kamala Harris turned off a part of the electorate,” Cobb says.

He expresses frustration with the well-rehearsed argument that Democrats became too fixated on “woke” identity politics at the expense of economic populism: “They make it seem as if these groups created identity politics. Almost every group that’s in the Democratic fold was made into an identity group by the actions of people who were outside.

“If you were talking about African Americans, Black politics was created by segregation. White people said that they were going to act in their interest in order to prevent African Americans from having access. Women, through the call of feminism, came to address the fact that they were excluded from politics because men wanted more power. You could go through every single group.”

Yet it remains commonplace to talk about appealing to evangelical Christian voters or working-class non-college-educated voters, he says: “The presumption implicit in this is that all those people see the world in a particular way that is understandable or legible by their identity, and so there’s a one-sidedness to it. For the entirety of his political career, Trump has simply been a shrewd promulgator of white-identity politics.”

That trend has become supercharged in Trump’s second term. He has amplified the great replacement theory, sought to purge diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and complained that museums over-emphasise slavery. His actions have built a permission structure for white nationalists who boast they now have a seat at the top table.

Many observers have also expressed dismay at Trump’s concentration of executive power and the speed and scale of his assault on democratic institutions. Cobb, however, is not surprised.

“It’s about what I expected, honestly,” he says, “because throughout the course of the 2024 campaign, Trump mainly campaigned on the promises of what he was going to do to get back at people. They’re using the power of the state to pursue personal and ideological grievances, which is what autocracy does.”

It is now fashionable on the left to bemoan the rise of US authoritarianism as a novel concept, a betrayal of constitutional ideals envied by the world. Cobb has a more complex take, suggesting that the US’s claim to moral primacy, rooted in the idea of exceptionalism, is based on a false premise.

‘Who has ever managed personal growth while constantly screaming to the world about how special and amazing they are?’

Jelani Cobb

He argues: “America has been autocratic previously. We just don’t think about it. It’s never been useful … to actually grapple with what America was, and America had no interest in grappling with these questions itself. Who has ever managed personal growth while constantly screaming to the world about how special and amazing they are?”

Cobb’s book maps an arc of the moral universe that is crooked and uneven, pointing out that, between the end of reconstruction and 1965, 11 states in the south effectively nullified the protections of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments of the constitution, imposing Jim Crow laws, voter suppression and violence to disenfranchise Black citizens.

“The constitution gave Black people the right to vote but, if you voted, you’d be killed and this was a known fact,” he says. “This went on for decade after decade after decade. You can call that a lot of things. You can’t call that democracy. It was a kind of racial autocracy that extended in lots of different directions.”

He adds: “We should have been mindful that the country could always return to form in that way, that its commitment to democracy had been tenuous. That was why race has played such a central role in the dawning of this current autocratic moment. But it’s not the only dynamic.

“Immigration, which is tied to race in some ways, is another dynamic. The advances that women have made, the increasing acceptance and tolerance of people in the LGBTQ communities – all those things, combined with an economic tenuousness, have made it possible to just catalyse this resurgence of autocracy in the country.”

It is therefore hardly unexpected that business leaders and institutions would capitulate, as they have in the past, he says: “We might hope that they would react differently but it’s not a shock when they don’t. Go back to the McCarthy era. We see that in more instances than not, McCarthy and other similar kinds of red-baiting forces were able to exert their will on American institutions.”

Cobb’s own employer has been caught in the maelstrom. In February, the Trump administration froze $400m in federal research grants and funding to Columbia, citing the university’s “failure to protect Jewish students from antisemitic harassment” during Gaza protests last year. Columbia has since announced it would comply with nearly all the administration’s demands and agreed to a $221m settlement, restoring most frozen funds but with ongoing oversight.

Cobb does not have much to add, partly for confidentiality reasons, though he does comment: “In life, I have tended to not grade harshly for exams that people should never have been required to take in the first place.”

He is unwavering, however, in his critique of Trump’s attack on the university sector: “What’s happening is people emulating Viktor Orbán [the leader of Hungary] to try to crush any independent centres of dissent and to utilise the full weight of the government to do it, and also to do it in hypocritical fashion.

“The cover story was that Columbia and other universities were being punished for their failure to uproot antisemitism on their campuses. But it’s difficult to understand how you punish an institution for being too lenient about antisemitism and the punishment is that you take away its ability to do cancer research, or you defund its ability to do research on the best medical protocols for sick children or to work on heart disease and all the things that were being done with the money that was taken from the university.

“In fact, what is being done is that we are criminalising the liberal or progressive ideas and centres that are tolerant of people having a diverse array of ideas or progressive ideas. The irony, of course, is that one of the things that happens in autocracy is the supreme amount of hypocrisy. They have an incredible tolerance for hypocrisy and so all these things are being done under the banner of protecting free speech.”

That hypocrisy has been on extravagant display again in the aftermath of Kirk’s killing by a lone gunman on a university campus in Utah. Trump and his allies have been quick to blame the “radical left” and “domestic terrorists” and threaten draconian action against those who criticise Kirk or celebrate his demise. The response is only likely to deepen the US’s political polarisation and threat of further violence.

Spencer Cox, the governor of Utah and a rare voice urging civil discourse, wondered whether this was the end of a dark chapter of US history – or the beginning. What does Cobb think? “There’s a strong possibility that it will get worse before it gets better,” he says frankly.

“We’re at a point where we navigated the volatile moment of the 1950s, the 1960s, because we were able to build a social consensus around what we thought was decent and what we thought was right, and we’re now seeing that undone. Indecency has become a new hallmark.

“But we should take some solace in the fact that people have done the thing that we need to do now previously. The situation we’re in I don’t think is impossible.”

Explore more on these topics:

Columbia University

US constitution and civil liberties

Race

US politics

interviews

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/11/10/voting-rights-and-immigration-under-attack

Voting Rights and Immigration Under Attack

The President’s goals were clear on the first day of his term, when he issued an executive order overruling the Fourteenth Amendment’s birthright-citizenship clause.

by Jelani Cobb

November 2, 2025

The New Yorker

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/11/10/voting-rights-and-immigration-under-attack

Sixty years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed two pieces of legislation that are, to a remarkable degree, animating forces in the most volatile aspects of the current political moment. In August, 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, a crowning achievement of the civil-rights movement which paved the way for the election of thousands of African Americans to political office in states where, previously, they were not even allowed to vote. Two months later, he signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, overturning the Immigration Act of 1924, which, by way of eugenics, had sought to curate an immigrant stock of white Europeans. Taken together, the laws democratized the idea of who could be an American, and also which Americans could freely exercise their rights at the ballot box. The Trump Administration and its Republican allies are now engaged in a concerted effort to return the United States to the landscape that preceded them.

The G.O.P. under Donald Trump, like many reactionary nationalist movements, is disproportionately concerned with demographics. Trump’s anti-immigrant crusade has reached a point where masked federal troops are snatching people from their homes—including an instantly infamous ice raid on Chicago’s South Side that involved a Black Hawk helicopter—their cars, their workplaces, courthouses, and public streets. Further demonstrating the nature of the President’s exclusionary vision, on Thursday the Administration announced that it will slash the number of refugees admitted to the U.S. next year to seventy-five hundred, with priority given to white Afrikaners. In addition, the Administration is insisting that universities accept fewer international students, recognizing that admission to such institutions is often the first step toward citizenship.

The Lede

Reporting and commentary on what you need to know today.

The President’s goals were made plain on the first day of his second term, when he issued an executive order defying the Fourteenth Amendment’s birthright-citizenship clause. The clause was written after the Civil War to affirm that emancipated native-born Black people were citizens, as was virtually anyone born in this country. But it has been targeted as a means of insuring that children born here without a parent who is either a citizen or a permanent resident are not automatically granted citizenship themselves. Courts blocked the executive order, so, in September, the Department of Justice asked the Supreme Court to take up the question of its legality. The attorneys general of twenty-four Republican-led states have urged the Court to act in Trump’s favor.

At the same time, the President’s desire to control which Americans’ votes will count has been manifested in the battle over congressional maps. The maps are typically revised every ten years, after the census. But three states—Texas, Missouri, and North Carolina—have redrawn their maps at Trump’s behest, creating potentially six more G.O.P.-held seats, and several others, including Louisiana, have taken steps to do the same. This is a transparent attempt to move the goalposts ahead of the 2026 midterms, when a three-seat shift would give Democrats control of the House of Representatives.

In response, at least five states with Democratic majorities are considering redrawing their maps. To counter Texas’s move, California put redistricting on its November ballot, which could give the Democrats five more seats, and voters appear set to approve the measure. In a perverse mirroring of a provision of the Voting Rights Act, the Justice Department is dispatching federal election monitors to some California districts.

But the potential impact of state efforts would likely pale in comparison with the one presented last month at the oral arguments in the Supreme Court case Louisiana v. Callais. In January, 2024, following court orders, Louisiana—which is allotted six seats in the House of Representatives, and where African Americans make up a third of the population—passed a map that created a second majority-Black district. In March, after a legal challenge, the state attorney general defended the map before the Supreme Court, asserting that it was consistent with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits drawing districts in a way that minimizes minority voters’ ability to elect their candidates of choice. (Strategically drawn districts were key in preventing African Americans from gaining political power prior to the civil-rights movement.) But a group identifying itself as “non-African American voters” has claimed that the protections enshrined in Section 2 are themselves discriminatory, in that they offer Black voters an entitlement not offered to non-Black voters. And Louisiana has effectively switched sides, arguing that the map it defended just last year should now be struck down.

Should the non-African American voters prevail, the ruling would set off a gerrymandering battle across the country. The case follows a Court ruling from last year, in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the N.A.A.C.P., which held that gerrymandering for partisan gain is permissible even when it diminishes the voting power of minority populations. In the oral arguments in Louisiana v. Callais, Janai Nelson, of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund, noted that referring to gerrymandering as partisan rather than as racial offered a distinction without a difference, given that roughly ninety per cent of African Americans in Louisiana are Democrats. The Court’s conservative majority appeared skeptical, but accepting the distinction ignores a crucial part of American political history; namely, that Black enfranchisement has always had partisan implications.

The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, which gave Black men the right to vote, was driven by Republican considerations that the newly enfranchised population would offset the political power of Southern Democrats, who had just nearly succeeded in tearing the country apart. Those considerations were central to the extralegal and violent tactics that subsequently disenfranchised Black people throughout the South for most of the twentieth century. The concern was not simply that Black suffrage implied a civic equality among the races but that Black people were not likely to vote for the segregation-friendly Democrats who then held power throughout the region. President Johnson privately predicted that empowering Black voters would spark a mass migration of white Southern Democrats to the G.O.P., which is precisely what happened.

Estimates of the net partisan effect of the current efforts vary, but what seems clear is that striking down Section 2 will almost certainly result in a landscape in which minority voters, particularly African Americans in the South, wield less political power than they have at any point since 1965. And it would bring Trump closer to shaping a nation that would look very familiar to those Americans who risked their lives to enshrine the very rights that he is trying to upend. ♦

Published in the print edition of the November 10, 2025, issue, with the headline “Civil Wrongs.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Jelani Cobb, a staff writer at The New Yorker and the dean of the Columbia Journalism School, is the author of “Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, 2012-2025,” among other books.

New Yorker Favorites:

An essay by Toni Morrison: “The Work You Do, the Person You Are.”

Jelani Cobb’s Three or More Is a Riot.

Photograph: One World

How We Got Here: Jelani Cobb on Rise of Trump & White Nationalism After Push for Racial Justice

Story

November 10, 2025

Topics:

Journalism

Donald Trump

White Supremacy

Black Lives Matter

Trayvon Martin

George Floyd

Racism

Student Protests

Immigrant Rights

Guest:

Jelani Cobb

staff writer at The New Yorker.

Links:

Jelani Cobb articles

"Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, 2012-2025"

Jelani Cobb, the acclaimed journalist and dean of the Columbia Journalism School, has just published a new collection of essays, “Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here.” The book collects essays beginning in 2012 with the killing of Travyon Martin in Florida. It traces the rise of Donald Trump and the right’s growing embrace of white nationalism as well as the historic racial justice protests after the police killing of George Floyd in 2020. “What we’re seeing is a kind reactionary push to try to return the nation to the status quo ante, to undo the kind of demographic change, literally at gunpoint, as we are pushing people of color out of the country by force,” says Cobb.

Transcript:

Transcript:

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Three or More is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here. That’s the name of a new collection of essays by Jelani Cobb, the acclaimed journalist, Dean of the Columbia Journalism School. The book collects essays beginning in 2012 with the killing of Trayvon Martin in Florida, it traces the rise of Donald Trump and the right’s growing embrace of white nationalism as well as the historic injustice protests after the police killing of George Floyd in 2020.

Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, quote, “We live in a time where writers like Cobb are being targeted by the highest powers in this nation. Read this book to understand why.” Jelani Cobb, thanks so much for being with us. Congratulations on the release of your book. Why don’t we just start off with the title? Three or More is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here. How did we get here, and where are we?

JELANI COBB: So, there’s an interesting kind of dynamic here. I wrote about this recently in that in the summer of 1965 – well, summer/fall of 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson signed two pieces of legislation that are really at the center of the kind of volatile politics that we’re dealing with now. In August, early August of 1965, he signed, famously, the Voting Rights Act, then in early October of that same year, he signed the Immigration – Hart-Celler’s Immigration Reform Act.

The Immigration Reform Act transformed the face of American immigration. It opened the doors for immigration from places like Africa, from India, from the Caribbean, from Latin America, places that had been widely prohibited for people from immigrating from in earlier versions of American immigration law. The Voting Rights Act changed the face of the American electorate.

What we’re seeing, and what I didn’t understand when I first started writing these essays, and I couldn’t because some of this history hadn’t played out yet – what we’re seeing is a kind of retrograde push or reactionary push to try to return the nation to the status quo ante, to undo the kind of demographic change, literally at gunpoint, as we see, and at the same time as we are pushing people of color out of the country by force, we are making space for specifically white South Africans. Not just South Africans, but specifically white South Africans.

And we see these cases being brought to try to diminish, if not completely eviscerate, the Voting Rights Act. And so, it’s trying to return to a kind of the old demography, or the demography of old. And as I was starting writing for The New Yorker in 2012, the first thing I wrote about was Trayvon Martin, who becomes this kind of almost inciting incident.

Black Lives Matter emerges out of that. And to a strange degree, a great deal of radicalization on the right comes out of that as well because just a few years later, we see the horrific murder of nine African-Americans in the church, in Emanuel AME Church in South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina. The person who was responsible for those homicides, Dylann Roof, said that he did it as a call to arms for white people, that he wanted white people to reassert their place and their primary position in American society, and that he had been radicalized by, of all things, the Trayvon Martin incident. And so, these things have kind of unfolded in a kind of tree diagram almost since then.

AMY GOODMAN: I remember we interviewed you first in Ferguson after the killing of Mike Brown.

JELANI COBB: That’s right, yeah. I remember that. Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Maybe we have that clip. But you have an essay in the book, “What I Saw in Ferguson.” You open it by quoting Richard Wright’s poem, “Between the World and Me,” about a lynching and how history’s an animate force. You write, “The dry bones stirred, rattled, lifted, melting themselves into my bones, and the gray ashes formed flesh, firm and black, entering into my flesh.” And then, you write, “I spent eight days in Ferguson, and in that time, I developed a kind of between-the-world-and-Ferguson view of events surrounding Brown’s death. I was once a linebacker-sized 18-year-old, too, and I saw then what Black people have been required to know is that there are few things more dangerous than the perception that one is a danger.”

JELANI COBB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Take it from there.

JELANI COBB: So, what we saw, even in Ferguson, which was, like, another stair step in this kind of ratcheting intensification of these dynamics – and this is happening in the Obama era, and the Obama DOJ is being – people are seeking some sort of assistance from the Obama DOJ in these instances. Or will this be different? Will the fact that there’s a Black president mean that this will be handled differently?

And at the same time, there is this kind of growing white allergic reaction to these social demonstrations. Now, Michael Brown was killed. His body lay in the street for almost four hours on an August day, a kind of blazing-hot August afternoon. And there is an entire community traumatized by there being a dead body, a person whom they know, who’s laying in the street for hour, after hour, after hour.

And out of that, there was another kind of step that we saw, and that was where kind of Black Lives Matter came into full fruition, and you began to see that movement grow and develop. On the other side of it, we’re kind of moving toward the reaction that enables Trump-ism, that enables when he comes down the escalator in Trump Tower in 2015, June of 2015 – coincidentally, he does this, comes down the escalator and announces his candidacy the day before the incident in which the nine people are killed in Charleston. Those things happened 24 hours apart. Not that there’s a causal relationship between these or anything like that. But it’s just this common response to the zeitgeist and the belief that somehow, white people have been pushed out of their ordained position in American society.

AMY GOODMAN: There’s a great deal of solidarity between African-American human rights movement and the Palestinian human rights movement. And also, the Jewish human rights movement. You are the Dean of the prestigious School of Journalism at Columbia University. You were there during the encampments and Columbia calling in the police several times. I’m wondering if you can talk about both situations.

One, the journalists, and a number of them from your own school. Journalists were seeing your school as a shelter. You even had a showdown with police, telling them to stop arresting journalists. If you can talk about the students at WKCR, Columbia Spectator, your own students, the graduate students in your school being attacked by police or arrested by police and the response of your university, Columbia.

JELANI COBB: I’ll just tell you, I’ve been doing this for a long time. It’s hard for me to believe, but I have been teaching for almost 30 years. I have never been more proud of a group of students than I was of those students who went out and reported. There were students who – and I didn’t encourage them to do it, as a matter of fact, I encouraged them to do the opposite, but there were students who were out doing 24-hour shifts, reporting on what was happening, filming, documenting.

One student, it was amazing because it was the exact right answer, but someone from The New York Times called me on my cell phone, and I was in the middle of doing a bunch of things, and I’m kind of running around, and they said, “Can someone give me, like, just some color about what’s going on on the campus?” And I hand the phone to a student, and I was like, “This is someone from _The Times–. They just want to know what’s going on,” and the student said, “Yeah, I have my own story to work on.” [Laughs] I thought that was great. That was the perfect response.

But they were really out there pursuing those stories. And in instances, I did have to come out and intervene because there were police officers, NYPD, once they got to the campus, and they were not making any distinctions, they were just kind of arresting people.

And I was like, “These are students, these are journalists. These are the kind of people” – at one point, someone threatened to arrest me, and it was just kind of, like, “It’s my job as Dean to work on behalf of my students.” And so, on the Columbia side, a lot of that is kind of privileged, but what I’ll say is that our interactions – in our interactions with everyone from the outside community, to inside, to the leadership, our kind of marching orders were to defend the freedom of the press and defend the First Amendment, and academic freedom and our students’ ability to report. That was the students from KCR, who weren’t even students at the Graduate School of Journalism, but students from the Spectator, which is the student paper, and the students who were enrolled at Columbia Journalism School. And that was what we articulated to the best of our ability.

AMY GOODMAN: And overall, as you talk about Notes on How We Got Here, President Trump’s attacks on universities, from Columbia to schools all over the country–

JELANI COBB: So, here’s the thing…

AMY GOODMAN: –and the connection between DEI and what he calls anti-Semitism.

JELANI COBB: Sure. On the first thing, one of the things that few people have noticed, or maybe people have noticed, but it hasn’t gotten a ton of attention, is that in all of these incursions into the autonomy of these institutions, one of the main things that the administration has demanded is that there’s some language about reducing the number of international students on their campuses. And this has been done because very often, acceptance into an American university, acceptance into American graduate school, is the first step in someone ultimately becoming a citizen.

They may graduate, they’ll get sponsored for a work visa, and then green card and then become a citizen. Or perhaps they marry someone. That’s the first step. And they’re attempting to foreclose that route. They’re attempting to reduce the number of people who are becoming naturalized citizens, and they’re using the pressures that they’re exerting on American universities in order to do so.

And it was convenient, I think, to use these kind of canards about DEI as a wedge issue to kind of – like, “Well, are you opposed to anti-Semitism, or are you in favor of DEI?” as if a person couldn’t hold both of those views. There was no natural reason that you couldn’t hold both of those views. But for a moment, this is kind of the rhetoric that we we receiving, the kind of propaganda we were receiving. And you would actually believe that these things are opposed or oppositional.

AMY GOODMAN: And if you can comment on just Friday, the Trump administration reaching a multimillion-dollar deal with Cornell University to restore more than $250 million in federal funding for the school, the Education Secretary saying, “The Trump administration secured another transformative commitment from an Ivy League institution to end divisive DEI policies.”

JELANI COBB: Yeah, I think this is ultimately an attempt – it begins with the kind of belief that no one who holds a position, unless apparently they are white men, is actually qualified or entitled to be in that position and that DEI, which has been an effort to look beyond the normal parameters of what had been natural – what had become routine parameters to hire the same people who had been in the same positions from the start of time, virtually, and to say, “We want our institutions to be inclusive of everyone who can possibly contribute to the institution.” That’s not a radical idea, but it has been reframed in such a way as a kind of zero-sum game, in which white men are being denied the positions that they should rightfully hold. And that’s what’s at stake here.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have Cornell – rather Columbia, your institution, will pay a $200-million settlement over three years to the federal government, also agreeing to settle Columbia investigations brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Do you see this as a huge concession? Are you critical of this?

JELANI COBB: See, a lot of that is kind of, like, privileged because I’m a Dean. What I’ll say is that I wasn’t happy with the situation at all. And what I tended to do was that I could exert my energy being kind of internally critical, or I could exert my energy about the fact that we should never have had to make those decisions in the first place. And so, my criticism has been that this is an unprecedented incursion into the autonomy of an institution of higher education, and it sets a terrible precedent.

And so, academic freedom has been infringed upon. The ability of even kind of to the point of making demands about particular departments and programs at a university. This is unheard of. This is not something that we’ve seen before, outside of the McCarthy period, which is the closest thing that we’ve seen. The great historian, Ellen Schrecker, had done her work on McCarthyism in higher education, and all of a sudden, we’re looking at these books about the 1950s and American universities–

AMY GOODMAN: We have 10 seconds.

JELANI COBB: –and seeing templates for what’s happening in the 2020s in American universities.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Jelani Cobb, I want to thank you so much for being with us. Dean of the Columbia Journalism School, Staff Writer at _The New Yorker_ magazine. His new book, Three or More is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here: 2012-2025.

I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Cobb on Trumpism, Racism Within GOP, the Election of Mamdani in NYC & More Pt. 2

VIDEO:

November 10, 2025

More from this Interview:

Part 1: How We Got Here: Jelani Cobb on Rise of Trump & White Nationalism After Push for Racial Justice

Part 2: Jelani Cobb on Trumpism, Racism Within GOP, the Election of Mamdani in NYC & More Pt. 2

Donate

Topics:

Journalism

Donald Trump

White Supremacy

Black Lives Matter

Trayvon Martin

George Floyd

Racism

Student Protests

Immigrant Rights

Guest:

Jelani Cobb

staff writer at The New Yorker.

Link:

Jelani Cobb articles

"Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, 2012-2025"

staff writer at The New Yorker.

Link:

Jelani Cobb articles

"Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, 2012-2025"

Jelani Cobb, the acclaimed journalist and dean of the Columbia Journalism School, has just published a new collection of essays, “Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here.” The book collects essays beginning in 2012 with the killing of Travyon Martin in Florida. It traces the rise of Donald Trump and the right’s growing embrace of white nationalism as well as the historic racial justice protests after the police killing of George Floyd in 2020. “What we’re seeing is a kind reactionary push to try to return the nation to the status quo ante, to undo the kind of demographic change, literally at gunpoint, as we are pushing people of color out of the country by force,” says Cobb.

TRANSCRIPT:

TRANSCRIPT:

Topics

Race in America

Donald Trump

Books

Author Interviews

Gaza

Zohran Mamdani

Academic Freedom

Trayvon Martin

Guest: Jelani Cobb

dean of the Columbia Journalism School

Watch Part 2 of our interview with acclaimed journalist Jelani Cobb, Dean of the Columbia Journalism School, about his new collection of essays, Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here. Cobb discusses many of the pieces in-depth, and also addresses the Heritage Foundation’s support for Tucker Carlson’s interview with white nationalist and Holocaust denier Nick Fuentes; New York City’s Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani; his students’ coverage of the Gaza encampment; ICE’s arrest of former Columbia graduate student Mahmoud Khalil; and how he got his start in journalism.

Donald Trump

Books

Author Interviews

Gaza

Zohran Mamdani

Academic Freedom

Trayvon Martin

Guest: Jelani Cobb

dean of the Columbia Journalism School

Watch Part 2 of our interview with acclaimed journalist Jelani Cobb, Dean of the Columbia Journalism School, about his new collection of essays, Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here. Cobb discusses many of the pieces in-depth, and also addresses the Heritage Foundation’s support for Tucker Carlson’s interview with white nationalist and Holocaust denier Nick Fuentes; New York City’s Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani; his students’ coverage of the Gaza encampment; ICE’s arrest of former Columbia graduate student Mahmoud Khalil; and how he got his start in journalism.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our conversation with Jelani Cobb, acclaimed historian, dean of the Columbia Journalism School and a staff writer at The New Yorker. His book is just out. It’s called Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, a 437-page collection of his essays from 2012 to 2025, with a bunch of postscripts.

I asked you about the subtitle, How We Got Here, in Part 1 of our conversation. What about Three or More Is a Riot?

JELANI COBB: That title came to me when I was in Charleston, and I was reporting on the trial of Dylann Roof, you know, the white supremacist who killed nine people in the church, Emanuel AME. And it reminded me that in 1739 there had been a slave revolt, the Stono revolt in South Carolina. And in the wake of that slave revolt, the colonial legislature passed a law that said the definition — effectively, the definition of a slave revolt was three or more Negroes, as they would have been called then, outside the presence of a white man. So, just the mere gathering of three people meant that this was forbidden. And it spoke to the kind of demographic anxiety of that era. And when I looked at what was happening there, what was the animating force behind Trumpism, you know, what was the animating force behind so much of what we were seeing in American politics, it went back to that same sort of demographic anxiety. And so, that’s where the title came from. And it’s Three or More Is a Riot.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to what’s going on right now, what some are calling a MAGA civil war, generated by an interview former Fox News host Tucker Carlson did with the white nationalist influencer Nick Fuentes, a Holocaust denier who praised Hitler many times, had dinner with Trump in Mar-a-Lago in 2022, well known as a white nationalist, as an antisemite, as a racist. Among his comments, and I could choose one of hundreds, a “bastardized Jewish subversion of the American creed. The Founders never intended for America to be a refugee camp for nonwhite people.” If you can talk about what’s happening here? The attack is that the head of the Heritage Foundation has supported Tucker Carlson in a very sympathetic interview with Nick Fuentes. What this white Christian nationalist movement represents?

JELANI COBB: So, I mean, I think there are a lot of things. If you actually look at the history of the Heritage Foundation, it kind of mirrors the Republican Party. Because I’m old enough to remember when the Heritage Foundation was — I mean, it was right of center. It was a right-of-center think tank, but it was nowhere near — they would not have come anywhere near the kind of xenophobic, antisemitic, overtly racist, Nazi-sympathizing kinds of politic that we see now. And it’s kind of similarly with the mainline GOP.

But what really is the conflict here is that the — and this, you know, goes all the way back to Charlottesville. There’s always been this attachment. From the earliest point of Trump’s emergence, there’s always been this attachment of this neo-Confederate, neo-Nazi element that has strongly and visibly been supportive of him. The problem is that they’re in the midst of their own culture war, in which they have accused the left of being the primary purveyors of antisemitism via any criticism they have for Benjamin Netanyahu, any criticism they have for the waging of war in Gaza, for what very many people have referred to as a genocide, all these things that are happening. And so, it gets in the way, and it becomes a bit of an embarrassment if you are making great political hay by flogging the left for these sins, and at the same time you have in your camp people who are overtly sympathizing with a person who oversaw the mass execution of 6 million Jews.

AMY GOODMAN: And then, where JD Vance fits into this picture? For example, the whole controversy around the text conversations of the white Republicans who referred to African Americans as animals —

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — talked a great deal about their sympathy with Hitler. While some of them were forced out of their positions, one of them left who was an elected official in Vermont — not so young, by the way.

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: You had JD Vance actually making a statement about “stop the pearl clutching.”

JELANI COBB: Right. Yeah, he did. He said that. He also — the same person who spoke in defense of the far right in Germany, specifically went to Germany to advocate on behalf of the far right. You can’t get a more leaden symbol than that. And so, this is, you know, a kind of playing footsie with these people and wanting to have — you know, for the portion of their electorate that still blanches at this kind of thing, they still want to have plausible deniability. But for — they’ve gone further and further and further. I mean, the poisoning, immigrants poisoning the American bloodstream, all these things that we have seen that are kind of standard textbook fascistic language and that tend to preface some sort of mass violence directed at vulnerable populations, and we’ve seen that become an increasingly prominent part of their rhetoric.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s talk about what happened here in New York, which has really shaken the foundations —

JELANI COBB: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: —of the establishment all over the country. And I’m not just talking about the Republican Party, but the Democratic Party, as well. And that is the election of the democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani, winning the New York mayoral race over the disgraced former Governor Andrew Cuomo. Yes, New York will soon have its first Muslim mayor, first South Asian mayor and the youngest mayor in over a century. This is part of what Mamdani said on election night.

MAYOR-ELECT ZOHRAN MAMDANI: The sun may have set over our city this evening, but, as Eugene Debs once said, I can see the dawn of a better day for humanity.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Zohran Mamdani on election night. If you can talk about the significance of his victory? As he was introduced, a thousand supporters and organizers — and that’s a really key point — of every hue, were there at the theater where he spoke, where he was celebrating his victory. Over 104,000 volunteers went out through the five boroughs, and a number of them were actual organizers working for all of these months to get Zohran Mamdani, the 34-year-old now mayor-elect of New York, elected.

JELANI COBB: You know, it’s really amazing. First off, that quote from Eugene Debs is particularly apt. If we wanted to play, you know, a probably interesting trivia game, it’d be like: Go back and find the last time that an American elected official quoted Eugene Debs. It will not be any time within — you know, that was recent. It’s certainly not quoting him favorably.

But the other thing that I think is significant here is that Debs, who really was the kind of avatar of American socialism for the moment that he existed in, was also dealing with a point at which the United States population had grown tremendously, largely by immigrants, driven by immigrants, and had been kind of advocating for a socialism that was both tolerant and inclusive and also looking at the common interests of all of these working people. And so, you know, the quote from Debs for a democratic socialist mayor-elect probably could not be more apropos.

The other thing about — thing that I think about it — and, you know, my colleague at Columbia, Basil Smikle, made a really good observation — is that Mamdani has put together, and the team around him has put together, this really broad array of New Yorkers around American — around kind of common interests, common economic interests, and the idea of it being a city that’s more affordable, etc. It’s a counterpoint, and it kind of harkens back to what we heard David Dinkins say in his rhetoric back in 1989, when he was elected as mayor, who kind of famously referred to the “gorgeous mosaic” of the city. With Mamdani, I think it becomes an even more pointed observation about bringing all of these different communities together, because it is a direct counterpoint to what we see in our national politics. And, of course, Mamdani being an assemblyman from Queens and his primary kind of target in that speech, or the person who he has the most pointed criticism from is — directed toward is a president who is, in fact, from Queens, too. And this is a internal conversation, Queens being the most diverse county in the United States, and this is a president who despises that dynamic, and a mayor-elect who embodies it. And I think that’s the subtext that we’re thinking about in this conversation.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, of course, Bernie Sanders endorsed him —

JELANI COBB: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: — as did AOC. And in Bernie Sanders’ book, It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism, he, too, quotes Eugene Victor Debs, Eugene V. Debs, who says, “The vast majority of Americans recognize that Eugene Victor Debs was right when he said, a century ago, [quote] “I am opposing a social order in which it is possible for one man who does absolutely nothing that is useful to amass a fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars, while millions of men and women who work all the days of their lives secure barely enough for a wretched existence.’”

JELANI COBB: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: And we happen to be speaking, Jelani, right at the moment where the USDA, the Trump administration, is threatening any state —

JELANI COBB: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — who dares to fill the gap —

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — to fully fund food stamps, SNAP —

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — for what? I think it’s one in eight Americans rely on SNAP —

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — to eat.

JELANI COBB: Right, yeah. I mean, so there’s that. And then there’s the other side. You know, it’s the hand that taketh and the hand that giveth, because of the extraordinarily lenient and beneficial policies that have been directed at the upper 1% of the 1% and the kind of vast accumulation of wealth that’s happening on the other side of it.

And so, I think that, you know, one of the other things I’ll say just really quickly about Mamdani is that it was interesting to hear the criticism that if he were elected, the moneyed class was going to flee the city or that they were going to react in this kind of way. It reminded me of when the NYPD was angry with de Blasio, and they decided that they were not going to enforce laws, but without realizing that this was exactly what people had been saying, that they had been overaggressive in enforcing particular kinds of laws. So, it was like, you’re going to punish me by giving me the thing that I have, in fact, asked for. And that’s not to say that kind of people are supposed to leave the city, you know, kind of flee, or any of these other kinds of things. But it is to say that people made the calculation that, you know, the rent is incredibly unaffordable for people. The subway system, which is our most democratic form of transportation, is severely lacking. Wages stagnate, all of these things that are happening, and we have had years of policies that favored the moneyed classes. And so, what will happen if we don’t have those policies anymore? Like, the things that people are worried about happening are already happening. And so, I think that was one of the kind of more notable things, you know, rhetorically, at least, in that campaign.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about this latest BBC headline, but go broader than that to what’s happening right here at home with the media. And you certainly comment on the media all the time. You follow it very closely. You have the top executives at the BBC abruptly resigning following backlash over the BBC’s edit of a speech made by President Trump, January 6th of 2021, before a mob of his supporters. The BBC is reportedly planning to formally apologize to Trump, who celebrated the resignation, saying on Truth Social, “These are very dishonest people who tried to step on the scales of a Presidential Election. … What a terrible thing for Democracy!” Trump repeatedly has defended unfounded claims that his 2020 loss to Joe Biden was rigged. So, you have the BBC top people resigning. You have both CBS and ABC paying $15 million and $16 million to President Trump, when, clearly, in both of those cases — in the case of CBS’s 60 Minutes, editing —

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — an interview with Kamala Harris. If this case had gone to court, it is hard to believe that CBS would have lost.

JELANI COBB: Sure, sure. So, I mean, of course, I mean, you know this probably, as well, better than anybody, that if you have any kind of raw material, you have — there’s an editing process that has to go. If you are — even in print, you know, if you’re talking to someone, and they say “um” 10 times, you’re not going to quote “um, um, um.” You’re going to, like, edit that out. And so, you know, this is generally done, as they will say, done for clarity and brevity. That’s what people will kind of say. And within those bounds, you know, that’s a kind of normal, acceptable thing. The line about the CBS interview and the kind of editing of it to make someone’s point more clear, well, that’s exactly what the point of editing is. And, you know, what I think a compelling kind of counterpoint would have been would have been to show the history of editing Donald Trump’s statements, because, you know, if you have someone who goes and takes five minutes to make a point, and you have 30 seconds for that segment, you’re going to actually try to make the person sound more cogent.

I haven’t seen the specific BBC edit, so I can’t comment on it. I know that, you know, there’s a kind of ongoing thing about it. But I do think the administration has likely been emboldened precisely because American news organizations caved in instances where at least the media lawyers who I have been in contact with and people who I discussed these other cases with, strongly felt that these were cases that would have been thrown out, that these were cases that didn’t really have a whole lot of legal weight to them, and by settling them for multiple millions of dollars, you only enhance the possibility that more news organizations are going to face that same sort of dynamic.

AMY GOODMAN: So, where do you see the media going today in this country? And what gives you hope? I mean, on the one hand, you have this fierce attack. Normally, what bullies do is they go after the weakest, but Trump is going after the most powerful, which is very efficient, because if they cave — and he has to count on them caving — it creates a chilling effect for everyone, because if he’s going to go after the big boys, people who don’t have those kind of resources are really afraid.

JELANI COBB: They are. But also, you know, some of the big organizations have vulnerabilities that other organizations don’t, quite frankly, because the leverage that’s been used against them has been their kind of corporate parentage and the desire for billion-dollar-generating mergers or various other kinds of things that they want to pursue. That was the case with The Washington Post and Bezos’ ownership of Amazon and his space programs and all these other kinds of things. That’s the case with Paramount. That’s the case with all these other kinds of things. Other organizations don’t necessarily have those same vulnerabilities.

And I’ll say that the one beneficial thing here is that the media ecosystem is still diverse, you know, not as diverse as it once was, but there’s still different types of news organizations. There are people like you doing what you do. There are nonprofit newsrooms. There are all kinds of different entities that are still trying to generate a baseline of knowledge for an informed public. And that might be, you know, our saving grace, at least for the moment.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about March 8th, International Women’s Day, though I don’t think that was the point of what happened on that day, but it was the day that Khalil — it was the day that Mahmoud Khalil was arrested. This day had a tremendous effect on you, as well. You were leaving to give a speech, leaving the country.

JELANI COBB: I was, yeah, on my way to — I was on my way to London.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what happened on that day?

JELANI COBB: So, I was on my way to — literally, I was on my way to JFK, and I got a message from one of the people who work in the dean’s office that Mahmoud had been arrested the night before. And so —

AMY GOODMAN: He had appealed, by the way, to the Columbia president before that, saying, “I am really afraid. I think” —

JELANI COBB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — “I might be taken. Can you help me?” because he was in Columbia housing.

JELANI COBB: He was in Columbia housing. Now, that story is a little bit more complicated than what’s known. And so, the fact of it is that Columbia did not assist in his arrest. I know that for a fact. Like, being, you know, a dean, I was part of those conversations. It did not assist and did not give access. If you notice, the people who arrested him followed someone else into the building, because they were not given legal access into the building.

AMY GOODMAN: I guess the question isn’t so much “Did they help in the arrest?” as “Did they help Mahmoud Khalil when he asked them to help, because he knew that they were closing in on him, and he was a student?”

JELANI COBB: Yeah, I think that if you were to talk to various other kinds of people in the administration, their version of this was that they didn’t give — there was no information given about his whereabouts. There was no access granted to his housing or any of those things. Aside from that, it’s kind of hard to imagine, like, what is in the university’s purview. But that was something that I knew as being a dean, that was part of the — I was privy to conversations surrounding that.

But the other part of it was that I was about — I was supposed to be in London for five days for different events, for a conference, for a talk.

AMY GOODMAN: You were giving a speech at Oxford?

JELANI COBB: I was giving a speech at Oxford. And so I decided that I would go, I would give the speech. I would still keep the thing. I didn’t cancel that event. But as soon as I gave the speech, I would then hop on a plane and come back. And that was what — you know, kind of how we proceeded.

Then we had kind of internal conversations. We talked with our alumni. We talked with, you know, our attorneys. We talked with all these other constituencies about what our students needed to know, what our international students needed to know, what were the vulnerabilities that we had, what were the protocols that we needed to follow. And, you know, we were trying to figure out, like, what our stance would be. We then, eventually — this was a little while down the line. I don’t remember, like, what the exact timeline was. But we, at the Journalism School, put out a statement kind of pointing to Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest being a tactic that would be used to stifle dissent on college campuses, that would curtail the vitality of the First Amendment and academic freedom and so on. And so, we put that out, and we got a good bit of criticism about it that was kind of anticipated, but that was kind of how we began, you know, to proceed and to figure out what we would do. And, of course, we did what the Journalism School does in a moment like that, which is that we started reporting.

AMY GOODMAN: Are you afraid for your international students, overall? I mean, he was an international student who already then had a green card, married to an American, and was well on the way to becoming a U.S. citizen. But there are those who are even more vulnerable, although, ultimately, he was jailed for months.

JELANI COBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: What is the climate like?

JELANI COBB: So, I think that when I went back to that McCarthy example, one of the things that there is a long history of — and, you know, again, it’s like my hat tip to my colleague Ellen Schrecker, who’s written about this extensively — is that there is a long history of using immigration law to suppress dissent in the United States, going all the way back to the Palmer Raids in 1919, 1920. But you go up through the 1930s, '40s, ’50s, and you find people who dissent or who have unpopular political views, and the primary tool for silencing them is to utilize immigration law. So this is not new. It's a replay of an older tactic that is fundamentally undemocratic and fundamentally contravenes, like, any concept of the First Amendment. If you have a First Amendment that only protects you when you agree with the administration, then you don’t have a First Amendment.

And so, I think that that is the grounds that people should look at, you know, the Mahmoud Khalil situation on, irrespective of whether you agree with him or not. It’s the fundamental question of his ability to articulate a viewpoint that may be supported by some people and may be outright despised by other people, but it’s still within the bounds of his right to express himself.

AMY GOODMAN: And then you have Rümeysa Öztürk at Tufts —

JELANI COBB: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — who writes an op-ed —

JELANI COBB: That’s even more overt.

AMY GOODMAN: — in her Tufts newspaper.

JELANI COBB: Even more overt, right, absolutely. I mean, we could just go through the line. There are just, like, instance after instance of this. And that’s why I think it’s important to kind of look and say this is not — this is a kind of habitual problem in American society with the criminalization of dissent, particularly by people who are immigrants or who have immigrant status. But it never — even if you don’t care about that, it never stops there. That always is an on-ramp for stigmatizing the speech of even broader groups of people who are dissenting. And so, there’s that concern, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Interestingly, Eugene V. Debs was jailed repeatedly —

JELANI COBB: That’s right. That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — because there was a law passed that you could not criticize World War I.

JELANI COBB: Yeah, that’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: And that’s exactly what he was doing. And he ultimately would run for president from jail.

JELANI COBB: Yeah, yeah. And what was it? He won 2 million votes or something? I forget what it was. Astounding.

AMY GOODMAN: Maybe a million.

JELANI COBB: Yeah, a million votes, astounding number of votes that he won running his presidential campaign from the Atlanta federal penitentiary, which was, you know, just an astounding thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us how you became a journalist, Jelani. Actually, go back to where you were born and talk about growing up, going to college, what this all meant to you and to your family.

JELANI COBB: Oh, so, I was — I was born in Queens, and I was raised in Queens. And, you know, aside from my family, one of the most foundational institutions in my life was the Queens Public Library, which was right around the corner from me. And I —

AMY GOODMAN: Weren’t you just honored there?

JELANI COBB: Yeah, I was, actually. I was. It was kind of amazing, because it’s like the full turn of the circle. But I still am astounded that in a country where we have the kind of regressive politics that we often do, we still have protected this institution that is so wildly democratic. We will let anyone walk in off the street and learn something. We won’t let anyone walk off the street and get healthcare, you know, which is terrible. It’s a travesty. But we have been able to protect this institution that lets people walk in —

AMY GOODMAN: You might want to say this quietly.

JELANI COBB: I know. Maybe I shouldn’t. I shouldn’t. I mean, I did joke. You know, the president of the New York Public Library is Tony Marx. And my ongoing joke with him is that, you know, the socialist scheme that you have, they’re hiding it in plain sight. They even have a guy named Marx running the place, and so… But it’s an amazing thing. And that’s where I spent, you know, many an hour in my youth. And I’m also proudly a product of Queens public schools. I went to P.S. 34 and I.S. 238 and — for middle school, and I went to Jamaica High School. And I wrote — one of the long essays in there is about Jamaica High School and its place in kind of American education.

And my parents had come to New York from the South. My father had a third grade education. My mother had a high school education. And they really poured everything into the idea that if I took school seriously, my life could be different than theirs had been. And, you know, it’s very much a kind of immigrant idea. But for them, it was the migrant idea, you know, coming from the South to the North.

AMY GOODMAN: In the Great Migration?